The Gaon’s Impact on the Interpretation of both Primary Sugyot in Zemanim

The Gaon’s Impact on the Interpretation of both Primary Sugyot in Zemanim

By William Gewirtz

Unquestionably, almost all ḥiddushim in the understanding of the vast literature on zemanim have halakhic implications. My intent is not to influence what has become minhag Yisroel; my focus is on establishing more precise halakhic definitions and theoretical innovations in sugyot that are central to the study of zemanim. Competent poskim can implement any changes in halakhic practice, which they determine that these innovations support.[1]

Two areas dominate the study of zemanim:

- How to determine precise delimiters for the day of the week, which concludes at the end of the period of bein ha-shemashot.[2]

- How to calculate the hours of the daytime period, which according to all opinions begins at alot hashaḥar.

Interestingly, in both Hebrew and English, the words yom and day denote both the daytime period and the day of the week. Our focus is on:

- the Gaon’s impact on the interpretation of two key aspects of Shabbat 34a-35b, which examines the transition between days of the week, and

- a key aspect of the Gaon’s clarification of Pesaḥim 94a focused on the daytime period.

The approach to the above sugyot were radically changed by the Gaon’s observations.[3] However, only the impact on the former sugyah in Pesaḥim is usually recognized.

As I strongly indicated in a paper on errors in halakhic reasoning, I do not believe that attempts to deal with the critique of Rabbeinu Tam’s position by the Gaon have ever been fully effective. In this paper, however, the focus is not on the extensive halakhic literature written primarily in the period of the aḥaronim, but on the text of the gemara itself and its interpretation by rishonim. The conclusions reached are very different.[4]

The first two sections address areas in the gemara beginning on Shabbat 34a where a significant modification to an earlier reading of the gemara, often associated with rishonim aligned with Rabbeinu Tam, is strongly preferred, but only when assuming a slight modification to the presumed opinion of the geonim / Gaon.[5] In a similar vein we suggest a modification to how the bein hashemashot interval is to be used, something I believe to be independent of the positions of Rabbeinu Tam and the Gaon.

The third section addresses the Gaon’s innovative reading of the gemara in Pesaḥim 94a, a reading that is strongly supported by both elementary logic and astronomy. Included in the Gaon’s reading is a concept that was never made explicit in rabbinic literature prior to the Gaon, to the best of my knowledge. As will become clear, that observation forms the basis for the Gaon’s challenge to the opinion of Rabbeinu Tam.

My observations are not intended to be judged as controversial, although concluding a sugyah may not have been correctly understood (or at the very least properly explained) until the 18th century might be jarring. It is beyond my focus or competence to deal with the implications of that observation; observations addressing that point would be welcomed.

Section 1: The endpoints of the period of bein ha-shemashot

The dispute between the geonim / Gaon and Rabbeinu Tam revolves around the placement of the interval of bein ha-shemashot, within the interval between sunset and tzait (kol) ha-kokhavim, whose length is (almost always) assumed to be the time needed to walk 4 milin.[6] The length of the bein ha-shemashot period is universally assumed to be the time needed to walk ¾ of a mil. It is normally assumed that

- the opinion of the geonim / Gaon places the bein ha-shemashot period at the start of that interval, while

- Rabbeinu Tam places it at its end.

Those two alternatives represent opposite extremes. Two adjustments seem reasonable.

- First, separate the dispute between the geonim / Gaon and Rabbeinu Tam into two distinct components:

- The first concerns the beginning and the second the end of the bein ha-shemashot period, subject to a constraint that the length of the bein ha-shemashot interval must equal the time to walk ¾ of a mil.

- Second, assume that there are multiple hybrid / intermediate positions, situated between the two generally assumed alternatives.[7]

This allows for

- an interpretation of the gemara in Shabbat similar (or according to some identical) to the overwhelmingly compelling position of the geonim / Gaon relative to the end of the bein ha-shemashot period,

- while defining the beginning of the bein ha-shemashot period using the textual approaches of many rishonim, albeit employing a significantly earlier point in time, much closer to sunset.

While I have not seen this conceptualization explicitly formulated[8] in the classic halakhic literature, practice and several pragmatic opinions are supportive of this approach. More importantly, the challenges raised to the opinions of both Rabbeinu Tam and the Gaon are, without exception, directed at the late ending of the Shabbat according to the opinion of Rabbeinu Tam and at the early beginning of the Shabbat according to the opinion of the Gaon.[9] This approach sidesteps the challenges to both opinions. Additionally, this approach absolutely disputes the view that

- Anyone who rejects the start of Shabbat precisely at or even a few minutes after sunset must embrace the approach of Rabbeinu Tam,

an assumption that does not follow logically, though it is occasionally found in the halakhic literature.[10]

There are numerous arguments in support for this position. We cite several of the strongest:

- The term mi-she-tishkeh ha-ḥamah: Ramban in Torat Ha-Adam[11] and the many ḥakhemai sforad who adopted his position stress that the meaning of the term mi-she-tishkehha-ḥamah unquestionably implies not sunset but a point after A simpler phrase shikiat ha–ḥamah would denote precisely sunset. Of course, mi-she-tishkehha-ḥamah does not imply any specific time but only that the time follows sunset by some number of minutes. The only change required is to assume that mi-she-tishkeh ha-ḥamah is referring to a point much closer to sunset, something that appears more reasonable than a point over 50 minutes later according to the (theoretical) view of Rabbeinu Tam. In other respects, the gemara is read like the numerous rishonim who assumed that mi-she-tishkeh ha-ḥamah cannot refer to sunset proper.

- Tosefet Shabbat:[12] Ramban argues that tosefet Shabbat could only begin after sunset during an interval that is still a part of the daytime period. Ramban does not consider tosefet Shabbat prior to sunset as meaningful, equating it to the value of illumination from a candle during daylight.

- The sugyah in Shabbat applies year-round, not only during a specific season or seasons: The gemara in Pesaḥim 94a, which equates the time needed to walk 40 milin with the daytime period, must assume an average day around either the spring or the fall equinox. In the Middle East, during a winter day of approximately 10 hours or a summer day of approximately 14 hours, the distance covered in one day would vary considerably. However, unlike the gemara in Pesaḥim 94a that can only apply to a 12-hour daytime period, the gemara in Shabbat, defines the end of Shabbat using terms like ḥashekhah, hiḥsif ha-elyon ve-hishveh le-taḥton and the appearance of three stars, all of which apply (nearly) uniformly throughout the year.[13]

At both the fall and spring equinox, the sun appears in the same place over the equator and you might expect Shabbat to begin and end at the identical time. Certainly, regardless of how one measures darkness, it is equivalently dark any number of minutes after sunset at those two times. However, in Jerusalem and other parts of the Middle East, unrelated to the degree of darkness, stars first appear a number of minutes later (after sunset) in the fall than they do in the spring.[14]Advantaged by the early appearance of Sirius and Canopus in the spring but not the fall, the Gaon restricts the focus of the gemara to the spring only.

Note that:

- All rishonim who choose to comment on the sugyah in Pesaḥim 94a state that the day in question occurs only around the spring (or fall) equinox.

- Not a single rishon makes an analogous comment, restricting the gemara beginning on Shabbat 34b to any specific time of year.

- Shmuel’s unchallenged statement:[15]With Prof. Levi’s table (provided in the appendix) as background, examine Shmuel’s unchallenged statement on Shabbat 35a, according to the position of the geonim / Gaon.[16] After discussing the appearance of the horizon and the length of the bein ha-shemashot period, the gemara states the opinion of R. Yehudah in the name of Shmuel who asserts: “one star – daytime, two stars – bein ha-shemashot, and three stars – night.”[17] This is followed by the opinion of Yosi (bar Adin) asserting that the stars in question are neither stars that appear in the day (i. e., large stars[18] or planets) nor small stars that only appear well after the time of tzait ha-kokhavim, but medium stars. How might Shmuel’s statement be reconciled with the previous discussion in the gemara?

- First, exclude the implausible suggestion that R. Yosi bar Adin’s assertion that Shmuel’s statement is referring to medium stars applies only to the third part (or second and third parts) of the text. Under this interpretation, the first part of Shmuel’s statement concerning one star, includes not only medium stars but also large stars or planets that are on occasion visible before sunset. Were that the case, the statement would be informing us that the appearance of a planet before sunset does not indicate that the bein ha-shemashot period has begun. In addition to being forced to argue that the different parts of Shmuel’s statement refer to different types of stars, such an assertion would hardly be necessary; the gemara gives no hint that the bein ha-shemashot period begins before sunset.[19]

- Second, because R. Yosef begins bein ha-shemashot at the time walk 1/12th of a mil later than R. Yehudah, some[20] align Shmuel’s statement and even pasken like R. Yosef, assuming that R. Yehudah start to bein ha-shemashot precisely at sunset, cannot be reconciled with Shmuel’s statement. Prof. Levi’s chart challenges that approach, since a delay of at most 2 minutes[21] (after sunset) provides no benefit; the first medium star cannot be seen until at least 6 minutes after sunset.

- Third, there are other (implausible) solutions that align Shmuel with Rabi Yosi only, some going so far as identifying the amora Yosi (bar Adin) as the tanna Rabi Yosi. To follow a sugyah focused on Rabi Yehudah, with an uncontested statement that accords only with Rabi Yosi is dubious, at best. Furthermore, Shmuel’s statement, which refers to the non-instantaneous, successive appearance of stars, is difficult to align with an opinion that the bein ha-shemashot interval is instantaneous.

The most plausible suggestion, like the view of R. Ḥaim Volozhin below, is that the bein hashemashot begins at least 6 minutes after sunset.[22]

- Seeing stars so early (even if only in the spring) is practically impossible:

If the start of the period of bein ha-shemashot for the geonim / Gaon is precisely sunset, there has been considerable effort[23] to align the appearance of three stars within the time it takes to walk ¾ of a mil after sunset. The only solution provided is to assume that the time needed to walk ¾ of a mil applies only around the spring equinox[24] [25] and, even then, to make yet further assumptions to arrive at so short an interval. Particularly if the time needed to walk ¾ of a mil is 13.5 minutes and even if it is a bit under 17 minutes, three stars can rarely be seen so soon after sunset and then

- only with great difficulty,

- by experts, perhaps aided by telescopes, and

- in a pristine environment absent urban sources of light, like the Judean desert.

Under no circumstances, is 13.5 minutes possible, and 16.85 minutes is almost equally unreasonable.[26]

- Multiple opinions that begin bein ha-shemashot slightly after sunset:

- 4 to 5 minutes: The minimum time reported as the custom of Jerusalem[27] as well as the opinion of R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi,[28] the point when the sun is no longer visible even from the highest elevations around Jerusalem.[29]

- Greater than 6 minutes: The opinion of R. Ḥaim Volozhin based on Shmuel’s statement concerning the appearance of a single star that is visible in the spring to an expert observer at that time.[30] The fact that R. Ḥaim Volozhin disagrees with his Rebbe, strongly suggests that the Gaon’s position that Shabbat starts at precisely sunset was only promulgated le’migdar miltah.

- 7 to 15 minutes: These views are supported by a variety of sources mentioned previously including R. Kapach’s view of Rambam and R. Posen’s view of the opinion of the geonim. A time around 10 minutes is implied by many Sephardi poskim who mention that until the call of the Moslem mugrab for their fourth prayer service, it is still day thus allowing for the performance of a brit on that day for a baby born in those few minutes after sunset on that same day one week earlier.

When linked to the times given in Prof. Levi’s charts, various alternatives from 6 – 16 minutes after sunset can be plausibly suggested. The next section on how the bein hashemashot interval was intended to be used will shed further light in determining how many minutes after sunset might still be considered daytime.

Section 2. Before or after

One aspect of the Gaon’s interpretation of Shabbat 34b, often assumed without further examination, is that bein hashemashot is calculated by adding its length to the beginning of the beginning of bein hashemashot period. That assumption will now be challenged. Though not conclusive as to how the sugyah should be read, some seforim of near contemporaries[31] of the Gaon assume the opposite approach, subtracting the length of the bein hashemashot interval from the end of Shabbat. The arguments below attempt to demonstrate that this approach may have been standard before the writings of the Gaon proliferated years later in the middle of the 19th century.[32] While some may argue that counting forward from sunset versus backward from nightfall is somehow tied to the fundamental makhloket of the geonim / Gaon and Rabbeinu Tam, there does not appear to be any logical, textual or halakhic basis for such an assertion.

The fundamental question is:

What possible value could there be in introducing (especially in an era before clocks) a time-based approximation that is a lower bound, season dependent, rarely applicable, and then only under rare, idealized conditions, at best? In what context would such information be useful?

Thus, I propose that the time needed to walk ¾ of a mil should be interpreted differently than the Gaon proposed and instead we will attempt to demonstrate that

- The time to walk ¾ of a mil is to be subtracted from the end of the bein ha-shemashot period as opposed to being added to its beginning.

- The period is not a minimum (that occurs only around the spring equinox), but a maximum (that occurs around the summer solstice). Thus, the entire sugyah is applicable year-round providing a conservative upper-bound to the length of the bein ha-shemashot

The arguments for both assertions are interrelated and are presented concurrently.[33]

- The gemara in Shabbat is primarily focused on Friday night and determining when the bein ha-shemashot period begins, as opposed to when it ends. The gemara assumes that the end to the period of bein ha-shemashot is known; each of the disputants are addressing when the period of bein ha-shemashot begins on Friday night. However, if the time needed to walk ¾ of a mil were meant to be added to the time of sunset, it would be addressing the end of the bein ha-shemashot period and not the beginning.

- The three fractions (each expressed as the time needed to walk a part (1/2, 2/3 and ¾) of a mil,) given as alternatives for the length of the period of bein ha-shemashot would then all have identical semantics; each of the three fractions (of the time to walk a mil) is counting back from the assumed point of ḥashekhah, to calculate the beginning of the bein ha-shemashot Given Prof. Levi’s chart, under no circumstances could anyone imagine that the time to walk either ½ of a mil after sunset could be the point at which Shabbat ends. The amoraim, R. Yehudah and R. Yosi, are quantifying the opinion of Rabi Yehudah in contrast to Rabi Nehemiah’s interval, whose period of bein ha-shemashot is only the time needed to walk ½ of a mil.

- If someone were countering the position of Rabi Yosi, who says the period of bein ha-shemashot is instantaneous, it is more likely that he would say that it can be “as long as” opposed to “as short ”

- The significant issue raised previously of never seeing stars as early as at the time needed to walk ¾ of a mil after sunset becomes entirely moot.

- The period of bein ha-shemashot has some practical consequence providing a potentially useable, conservative upper bound as opposed to a purely theoretical lower bound, which is of limited to no use.

- As noted earlier, rishonim, who limit the gemara in Pesaḥim to the equinox periods in the fall and spring, make no such assertion with respect to the gemara in Shabbat. One might presume from the lack of commentary that rishonim assumed that the sugyah applies year-round.

Treating the gemara in Shabbat like the gemara in Pesaḥim as referring only to days around the spring (but not the fall) equinox[34] is unnecessary when thinking of the interval as a practical upper bound. All the other descriptions in the gemara, either the appearance of the sky / horizon or the visibility of three stars, apply year-round.

Now examine the three elements in combination:

- The various opinions of rishonim on the time to walk ¾ of a mil – 13.5, 16.85 and 18 minutes.

- Levi’s chart indicating that 3 stars are visible to a careful observer 30[35] minutes after sunset in the summer.

- The two suggested interpretations that

- delay the beginning of bein hashemashot to a point slightly after sunset, and

- view the sugyah as subtracting the length of bein hashemashot from its end to find its beginning.

We can then assume that Shabbat begins from 12 (subtracting 18 from 30) to 16.5 (subtracting 13.5 from 30) minutes after sunset.[36] However, given

- very natural and expected stringency that occurs even today but certainly are to expected in an era before (widely available and accurate) clocks, and

- the need for tosefet Shabbat

practiced times for starting Shabbat between 5 and 10 minutes after sunset ought not be surprising.

Section 3. The Gaon’s approach to Pesaḥim 94a.

The Gaon’s approach to Pesaḥim 94a is premised on an incontrovertible astronomic and logical fact. Assuming that alot hashaḥar approximates the first light of the day, then its evening counterpart, tzait ha-kokhavim, must occur when the sun’s illumination has (next to) no remaining effect.[37] At both of those times, all stars that are in position to be seen are not obscured by illumination from the sun. As a result, the Gaon adds the word kol to differentiate tzait ha-kokhavim, which throughout the Talmudic literature refers to the appearance of 3 stars, from tzait kol ha-kokhavim, the appearance of “all the (potentially visible) stars.” Of course, this point demolishes[38] Rabbeinu Tam’s interpretation that is predicated on the assumption that the meaning of the term tzait ha-kokhavim occurring in both Pesaḥim 94a and Shabbat 35a is the same. Slightly reformulated the Gaon asks how could the time of the appearance of only three stars and the time of alot hashaḥar, when (almost) all the stars are still visible, be separated by intervals of identical length from sunset and sunrise respectively? The pre-dawn counter point to the time after sunset when (only) three stars are first visible cannot be alot hashaḥar when (almost) all stars are still visible.[39]

This ḥiddush is not unexpected, even though the gemara in Pesaḥim is the primary sugyah used throughout halakhic history to provide a source for determining the time of alot hashaḥar. Despite that halakhic application, the sugyah is focused primarily on geography and astronomy. Thus, harmonious use of the term tzait ha-kokhavim with its use elsewhere in Talmudic literature, which Rabbeinu Tam assumed, need not be presumed.

Since the notion of tzait kol ha-kokhavim is new, it is also not surprising that the Gaon did not specify, to the best of my knowledge, any halakhic uses for the notion of tzait kol ha-kokhavim. Of course, those who followed Rabbeinu Tam’s position had no reason to even consider a point in the evening after tzait ha-kokhavim.

However, that changed with the arrival of what we colloquially call the Brisker methodology. Talmudists of that school have produced potential halakhic implications. For example, it is not difficult to differentiate between:

- halakhot tied to a specific day or those that are to be performed every day,

- from those that have no connection to any specific day but are restricted to being performed only during the daytime period.

Presumably, the construction of the Beit HaMikdash is a straightforward example. While there is a daytime requirement,[40] there is no constraint on which day of the week that construction should take place. Another example, which does not comport with the above ḥiluk, has been proposed by R. Moshe Soloveitchik. He suggested the use of tzait kol ha-kokhavim as a delimiter for tosefet Shabbat according to those following the Gaon. While Shabbat ends at the time of tzait ha-kokhavim, R. Soloveitchik proposed that tosefet Shabbat is meaningful only until tzait kol ha-kokhavim.

While these examples[41] are noteworthy, the lomdus of a yartzeit shiur by R. Joseph Soloveitchik was astonishing. Effectively, but not explicitly, R. Soloveitchik disregarded both historic interpretation and practice when he transformed Rabbeinu Tam into an early supporter of the notion of tzait kol ha-kokhavim.[42] As presented in that shiur, though expressed slightly differently, the dispute between the Gaon and Rabbeinu Tam revolves around whether Shabbat ends at tzait ha-kokhavim or tzait kol ha-kokhavim.[43]

In R. Soloveitchik’s formulation, the Gaon defined a critical point along a continuum beginning at the point of sunset, when there is almost complete exposure to the sun’s illumination, and ending at the point of tzait kol ha-kokhavim when no noticeable impact from the sun’s illumination can still be detected. That critical point occurs roughly when 3 medium stars first become visible and marks the transition point between days of the week according to the geonim / Gaon. Rabbeinu Tam, however, according to R. Soloveitchik’s formulation, defined the transition between days of the week at the point when the sun’s impact has ended entirely, a point corresponding to the end of the continuum, at tzait kol ha-kokhavim.[44]

A possible approach that R. Soloveitchik did not employ is that the Gaon and Rabbeinu Tam decided differently based on two conflicting sugyot in Shabbat and Pesaḥim, respectively. Of course, that would be at variance with Rabbeinu Tam’s normal methodology for resolving conflicting sugyot. Rabbeinu Tam tends to distinguish between sugyot, something he does explicitly with respect to these sugyot, as opposed to declaring sugyot in conflict and deciding between them. The principal motivation for even raising such a possibility is R. Soloveitchik’s complete avoidance of any mention of the challenges to Rabbeinu Tam’s position from the sugyah in Shabbat. This leads me to wonder if in R. Soloveitchik’s ahistorical reformulation of Rabbeinu Tam, and for reasons entirely unstated, R. Soloveitchik gave the sugyah in Pesaḥim prominence and preference over the sugyah in Shabbat according to Rabbeinu Tam.

Conclusions:

It is not at all usual to treat a ruling of the Gaon as le’migdar miltah. However, three things increase my confidence that I am correct in this instance.

- The reality as described in the epistle of the Ba’al ha’Tanya referenced earlier, who lived at the same time and in the same general area, clearly describes people working beyond 30 minutes after sunset, something that the Gaon would be motivated to prevent as resolutely as possible.

- The opinion of R. Ḥaim Volozhin, in open disagreement with the Gaon’s stated position, demands a reconciliation of views.

- The textual arguments made by rishonim, the halakhic writings and positions of noted aḥaronim, and the various arguments that I have formulated appear convincing.

What should be noted is the Gaon’s interesting ability to impact not just pesak, but the way we (perhaps even unconsciously) approach the study of sugyot.

Appendix

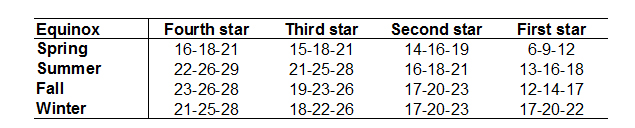

Prof. Levi’s Table

The three times listed in each cell of the table correspond to how difficult it is to see a star.

- The shortest time noted is when an expert who knows exactly where to look can observe a star.

- The intermediate time noted is when a star can be seen with great difficulty.

- The third time noted is when a careful observer can see a star.

The time when stars are visible to a casual observer, is yet later.

[1] My assumption is that poskim may find the innovations useful in exceptional situations as opposed to more typical ones.

[2] According to the vast majority of rishonim, the day ends when bein ha-shemashot ends or at most 2 minutes later.

[3] Familiarity with both sugyot is assumed to fully assess this essay.

[4] See my article in Hakirah spring 2019 for more detail on the Gaon’s convincing attack on Rabbeinu Tam’s position.

[5] A version of that reading is presented in Ohr Meir as the opinion of the geonim, who R. Posen seeks to demonstrate conflict with that of the Gaon. What the Gaon felt mei ikar ha’din can be disputed as will be illustrated. Even if one were to reject any variation of the Gaon’s stated position, this paper can also be considered to apply to the less specific view of the geonim.

[6] Both 72 or 90 minutes are increasingly assumed to apply only in the Middle East around both equinoxes and require adjustment (using depression angles) to account for variation by season and latitude.

[7] These positions are more properly characterized as variants of the position of the geonim / Gaon as they are all much closer to their normally assumed period of bein ha-shemashot.

[8] Throughout R. Kapach’s commentary on Mishnah Torah, however, he asserts that this is the position of Rambam. See R. Posen’s view as well, mentioned in footnote 5.

[9] This seminal point was made explicitly by R. Chaim Sonnenfeld in teshuvah 33 (an approbation to a sefer on zemanim) in a recently published volume of his teshuvot. His reaction, as might be expected, was to be maḥmir, and fulfill the stringencies of both opinions. I argue that the strengths of both opinions lead to the opposite and more probable conceptual position, adopting the leniencies of both positions.

[10] See Vol. 2 of HaZemanim BeHalakha by R. Ḥaim Benish, page 360, especially footnote 58.

[11] Pages 251 – 252, Chavel edition, Mossad Ha-Rav Kook.

[12] This argument is included due to its ancient provenance; it is easily challenged given that it is normally assumed that tosefet Shabbat can begin at plag ha’minḥah, which precedes sunset.

[13] Note as well, that the gemara in Pesaḥim 94a applies to

- a day of average length,

- which occurs around both the spring and fall equinox.

However, the days that would be referred to in Shabbat 34b would be

- a minimum, as opposed to an average, and

- restricted to those days when the appearance of three stars occurs within the time needed to walk ¾ of a mil after sunset. For astronomic reasons such days occur only in the spring and not in the fall.

While neither of these two differences is itself convincing, both lend further support to the thesis developed.

[14] See the chart by Prof. Levi provided in the attachment.

[15] A more extensive analysis of Shmuel’s statement will appear in a future issue of the Torah u’Maddah journal.

[16] This section assumes detailed familiarity with the sugyah on Shabbat 34b-35b.

[17] Prepositions have been omitted from the statement in order not to bias the semantics.

[18] Large stars are defined as kokhavei lekhet, moving stars, currently called planets. Other approaches to dividing stars into categories are much less likely and not considered.

[19] The isolated opinion of R. Eliezer mi’Mitz, who begins the bein ha-shemashot period before sunset, is difficult to reconcile with Shmuel’s statement, in any case.

[20] See the last two paragraphs on page 358 and especially footnote 50 in Vol. 2 of HaZemanim BeHalakha.

[21] The time to walk 1/12 of a mil is between 1.5 and 2 minutes.

[22] While normally I would assume Prof. Levi’s third entry matches Shmuel’s assertion, since this statement might mean seeing a star does not mean bein ha-shemashot has necessarily begun, it might mean just an accidental sighting, which may occur at the earliest time possible when normally only an expert, knowing exactly where to look, can locate a star.

[23] R. Benish, R. Willig, Prof. Levi among many others struggle with this issue.

[24] In the spring Sirius and Canopus can both be seen around 15 minutes after sunset.

[25] Having seen no earlier discussion of this issue anywhere in the halakhic literature, I believe this interpretation originated with the Gaon in O. Ḥ. 261. The alternative under discussion, delaying the start of bein ha-shemashot by some small number of minutes after sunset, eliminating the hypothesis that bein ha-shemashot begins precisely at sunset, which leads to such questions.

[26] Perhaps one can assume some worsening of atmospheric conditions, as a result of pollution, slightly decreasing visibility. I spoke with a chemist in my synagogue, Dr. Irwin Goldblatt, who verified this as a possibility. I have no basis to determine how accurate this observation might be, but it is hard to imagine that it is consequential.

[27] See Minhagei Eretz Yisrael by R. Gliss, pages 102 and 282.

[28] Seder Hakhnosat Shabbat, found towards the end of every Ḥabad siddur, specifies 4 minutes. He reverses the position he took in Shulḥan Arukh HaRav, which supported Rabbeinu Tam.

[29]See Zemanim Ke’hilkhatam by R. Boorstyn, chapter 2, section 3, where he summarizes different 19th and 20th century posekim in the Middle East who supported times beyond 4 to 5 minutes and up to approximately 10 minutes after sunset. The rationale he and many of these posekim used is varied often relying on the notion of sea level and / or visibility from higher elevations, a topic of continued debate.

[30] See the addition to Maaseh Rav section 19. Six minutes is expressed as 1/10th of an hour to be applied in both the morning and evening, although Shmuel’s assertion of “one star – daytime” is given as the reason for the slight delay after sunset. How R. Ḥaim Volozhin determined this precise time that equals the time at which an expert can see Sirius remains a mystery.

[31] R. Adler, R. Loerberbaum, and R. Sofer all subtract the length of the bein hashemashot interval from the end of Shabbat, see my article, Zemannim: On the Introduction of New Concepts in Halakhah, in the TuMJ 2013.

[32] It goes without saying that the instantaneous communication that characterizes of our current environment cannot be anachronistically assumed in a prior period. This impacts the assumptions made about when some of these sources are read / known, a topic not pursued further.

[33] A set of arguments based on the statement of Shmuel about 1, 2 and 3 stars are not included and will be incorporated in a future paper examining both Shmuel statement and Rambam in multiple sections of Mishnah Torah, based on their mastery of astronomy as it was known in their times.

[34] First suggested by the Gaon in O. Ḥ. 261, this approach is widely assumed in recent halakhic literature. Note that the gemara in Pesaḥim assumes an average day, which occurs in both the spring and fall around the equinox. However, the Gaon’s argument assumes, not an average interval, but a minimum interval and one that occurs only in the spring, but not in the fall; stars are not visible as early in the fall as in the spring. On the other hand, as suggested, a maximum would apply year-round.

[35] Prof. Levi uses a depression angle normalization to spring, which we will not explain. His use of 28 is in fact closer to 30 minutes, as normally defined by clock-time.

[36] 12 – 13 minutes is consistent with the many rishonim supporting a time to walk a mil of 22.5 minutes.

[37] There is no reason to debate whether the underlying science favors either of the two most common halakhic definitions, which sandwich current technology’s identification of the point at which the first light of the sun is visible. Expressed as depression angles the 72- and 90-minute intervals equate to depression angles of approximately 16 and 20 degrees, respectively. With the best available equipment, light from the sun can be observed at a depression angle of approximately 18 degrees. One can then argue that 16 degrees is when the amount of light is visible to humans, while 20 degrees is when one arises in anticipation of emerging light. Both are reasonable positions for defining alot hashaḥar.

[38] So strong a word is intentional given the “bombe” kasha of the Gaon; see immediately below.

[39] R. Moshe Sofer might be trying to deal with this point about a symmetric point to the appearance of three stars in his commentary on Shabbat 34.

[40] See Rambam, Hilkhot Beit Ha’Beḥirah (1:12). Rambam’s formulation is originally stated in the negative, which raises possible questions that might be analyzed in this context.

[41] Other possible examples include the operation of a beit din, the laws of aveilut, particularly the first day, etc.

[42] The philosophical underpinnings that would enable such ahistorical ḥiddushim is beyond the scope of this article. Despite an accusation of partiality, one cannot dismiss the assumption that R. Soloveitchik was aware of the various challenges to his ḥiddush. Despite bringing support from the period of the rishonim, I believe the Rav was establishing what he knew to be a restatement of Rabbeinu Tam’s position, based on the undeniable accuracy and correctness of the Gaon’s notion of tzait kol ha-kokhavim. In my own mind, I have played out a long and imagined conversation with R. Soloveitchik on this subject.

[43] For any number of reasons, it is difficult to imagine the perspective presented was that of Rabbeinu Tam. Rather, it might represent Rabbeinu Tam’s position updated and enhanced by what is now known scientifically.

[44] What I also do not understand is why R. Soloveitchik referred to the mathematical notion of continuity as opposed to any astronomical knowledge, which I think would have been more relevant.