A Newly Discovered Work of the Rambam?

A Newly Discovered Work of the Rambam?

By Eli Genauer

I recently purchased a Chumash which was printed in Sulzbach in 1741 by Meshulam Zalman ben Aharon Fraenkel

Marvin Heller succinctly sums up the history of Hebrew printing in Sulzbach as follows:

“This small Bavarian community was for over two centuries the site of Hebrew presses that printed many important titles. Duke Christain-Augustus due to his interest in Kabbalah, permitted the opening of Hebrew print shops in the 1660’s. Sulzbach was subsequently home to Hebrew presses belonging to Isaac Kohen Gersonides, Isaac ben Judah Loeb of Prague, Moses Bloch, and afterwards the Frankel-Arnstein family which printed books there from 1699-1851.”[1]

The bibliographic record at the NLI, most likely copied from the cover page of the book, notes nothing very unusual about it.

http://aleph.nli.org.il:80/F/?func=direct&doc_number=000333882&local_base=MBI01

עם שלשה [פירושים]… רש”י ז”ל, עם רש”י ישן, גם הפירוש רבינו יחזק’ בעל חזקוני, ובעל הטורים [לר’ יעקב ב”ר אשר] וכל הספר תולדת אהרן [מאת ר’ אהרן מפיסארו], וחסירות ויתירות וקרי כתיב… גם הפטורת [!] ופירוש המילות. והוגה בעיון רב…

One line that stands out a bit though, is one which indicates that there is a Peirush Hamilot for the Haftorot

… גם הפטורת [!] ופירוש המילות.

It also notes that there are separate title pages for the Chamaish Megillot and Haftorot

סד דף, עם שער חלקי: “חמש מגילות… עם פירש רש”י”, וכן ההפטרות לכל השנה.

This bibliographic record comes from The Bibliography of the Hebrew Book (מפעל הביבליוגרפיה העברית)

We are informed on the NLI website that “The recording of the books is done in a scientific manner according to rules set by an editorial staff led by Prof. Gershom Scholem and Prof. Ben – Zion Dinur, and was based on examination of the books themselves. It includes a full description of the contents of the book and accompanying material, as well as all participants in its composition: editors, translators, authors of forewords and introductions, interpreters and illustrators and more.”

It seems though that the bibliographers missed a very unusual and important feature of this Chumash.

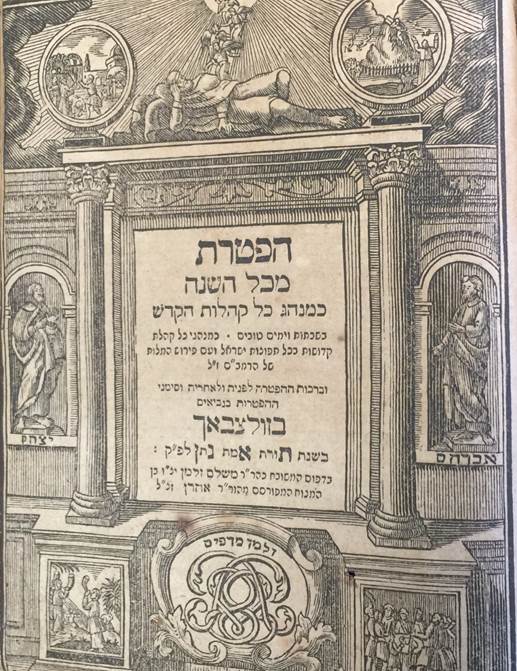

Here is the separate cover page for the section on Haftorot:

This title page contains the following information

” כמנהגי כל קהלת קדושות…..ועם פירוש המלות של הרמב״ם ז״ל“

“According to the customs of all the holy communities…with a “Peirush Ha’Milot” of the Rambam.”

This information is also included in the preface portion of the Chumash section under the title of אמר בעל המדפיס:

![]()

“גם ההפטרות ופסקי טעמים מדוקדק…עם פירוש המלות של תורת משה הרמב״ם..”

There seems little doubt that this Peirush Hamilot is being attributed to the Rambam.

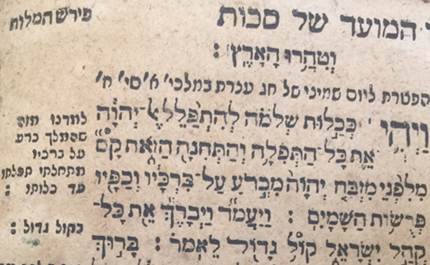

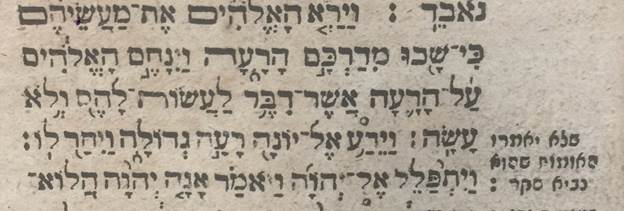

Here is what one page looks like.

An example of a “Peirush Hamilot” would be the words “קול גדול” being interpreted as “בקול גדול”

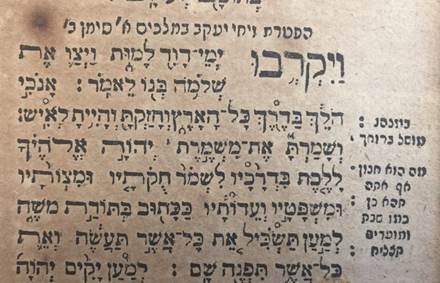

However, this other page evidences differences in methodology in the “Peirush Hamilot”.

“בדרך” is just translated as “במנהג.”

But “והיית לאיש” is expanded upon and explained as “מושל ברוחך”

“בדרכיו” is also very much expanded upon by saying exactly which paths should be followed: “מה הוא חנון אף אתה תהא כן”.

In this section below, we are told that the four Metzoraim are Gechazi and his three sons, a comment mirroring Rashi and Radak:

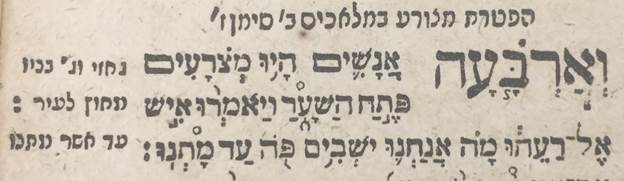

In the story of Yonah, we are told that he was troubled that Hashem had forgiven the people of Ninveh.

The Peirush HaMilot explains that it was because he did not want to be thought of as a false prophet. This is similar to Rashi’s approach:

I had never heard of such a commentary on Navi by the Rambam and was not able to find any reference to it anywhere. I checked with numerous experts in the field and no one else had heard of it either.

Imagine that! A work ascribed to the Rambam showing up in Sulzbach in 1741 and seemingly never to be heard from again. The printer gives us no hint of its origin and treats it as if it were a known work.

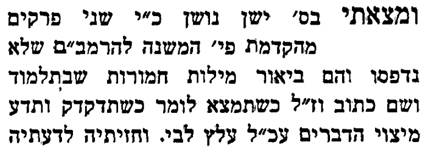

There is more, though. There is a fascinating reference to the Sulzbach Chumash of 1741 by none other than Rabbi Reuven Margoliot.[2] In a lengthy discussion of names that are missing from the Rambam’s Hakdamah to Peirush HaMishnayot, Rabbi Margoliot posits there is a portion of this Hakdamah missing from our printed editions and expresses the hope that

״ואולי תוחזר לנו האבדה הגדולה שני פרקים מהקדמת רבינו זו שהושמטו בהעתקות ולא נדפסו״

As a proof that there are missing chapters, he quotes from the Chida who writes:[3]

״מצאתי בספר ישן נושן כת״י שני פרקים מהקדמת פירוש המשנה להרמב״ם שלא נדפסו, והם ביאור מלות חמורות שבתלמוד״

In a footnote Rabbi Margoliot then makes a connection between the “lost” “ביאור מלות חמורות שבתלמוד” and the פירוש המלות של הרמב״ם ז״ל״” which appears in the Sulzbach Chumash of 1741.

״בחומש דפוס זולצבך תק״א בחלק ההפטרות מכל השנה הנלוה לתורה עם פרש״י וחזקוני הוא רושם שכולל פירוש המלות של הרמב״ם ז״ל״

Finally, by only citing this Chumash as containing the Peirush HaMilot, Rabbi Margoliot seems to be indicating it was the only time it was published. It certainly is a rare find for a Chumash printed in 1741.

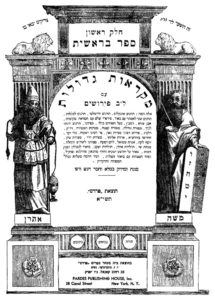

*Seforim Blog editor’s note: The Warsaw 1860 Mikraot Gedolot included this perush hamilot (calling it haftarot im biur hamilot on the title page) but does not give the attribution to the Rambam, or to anyone. Some of the content are word for word quotations of Rashi in the print editions. Here is the title page (from a 1951 photo offset reprint):

[1] Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book by Marvin J. Heller- Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2008.- p.40.

[2] Nitsotse or : heʼarot be-Talmud Bavli ṿe-heʻarot be-divre gedole ha-rishonim ṿeha-aḥaronim. Reuven Margoliot. Yerushalyim, Mosad Ha-Rav Kuk, 2002, p.34. The discussion of the missing names starts on page 30. The footnote cited is footnote 29 on page 34. My appreciation goes to a fine young scholar named Yosef, who brought this source to my attention.

[3] Sefer ʻEn zokher, Chaim Joseph David Azulay, Yerushalayim, 1962. p.185 #29