The Fish Motif on Early Hebrew Title-Pages and as Pressmarks

by Marvin J. Heller

Fish are a symbol replete with meaning, among them, in Judaism, representing fertility and good luck, albeit that fish are not an image that, for most, quickly comes to mind when considering Jewish iconography. Created on the fifth day of creation, fish symbolize fruitfulness, and, as Dr. Joseph Lowin informs, the month of Adar on the Hebrew calendar (February-March, Pisces) is considered “a lucky month for the Jews (mazal dagim).” He adds that in Eastern Europe people named sons Fishl as a symbol of luck, and that in the Bible, the father of Joshua is named fish, that is, Nun, which is fish in Aramaic.[1] Similarly, Ellen Frankel and Betsy Platkin Teutsch note the allusion to fertility and blessing, the former that when Jacob blesses Ephraim and Manasseh, Joseph’s sons, he says “May they multiply abundantly ve-yidgu, like fish) in the midst of the earth” (Genesis 48:16) and the latter to the Leviathan, the great sea monster the Jews will feast upon in the messianic age.[2]

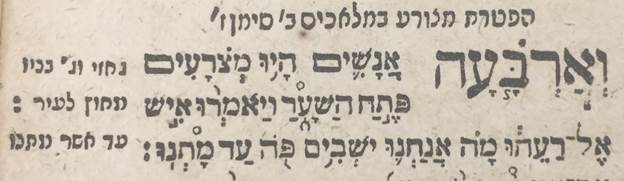

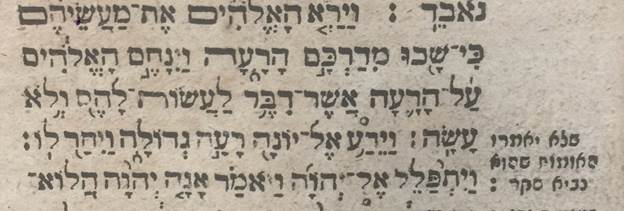

Other biblical references to fish include Dagon, the fish-god of the Philistines, also worshipped elsewhere in the Middle East, mentioned several times in the Bible (Joshua15:41, 19:27; Judges 16:23; I Samuel 5:2–7; and I Chronicles 10:10). A fish also appears in the biblical story of Jonah, a large fish (dag gadol), not the popular whale that swallowed the prophet.

Not only Jewish sources and printers used devices that were fish related. The Medjed fish, a species of elephant fish, a medium-sized freshwater fish with a long downturned snout, abundant in the Nile, was worshipped at Oxyrhynchus in ancient Egypt and appears in Egyptian art. Fish are a not infrequent image on medieval coat of arms. Indeed, there are as many as 181 shields of salmon alone in heraldry.[3] The most well-known printer device with a fish is the anchor and dolphin of Aldus Manutius (1449-1515), albeit not strictly speaking a fish, as a dolphin is actually an aquatic marine mammal. Among the most novel of the marine pressmarks is that of the Liege printer J. M. Hovii, active during the latter half of the seventeenth century, whose mark consisted of a mermaid enwrapped about a tree with a skull at the foot of the tree.[4]

This article is the most recent in a series describing printer’s devices and motifs appearing on the title-pages and with the colophons of early Hebrew printed books.[5] The use of the fish images described here are varied, comprised of pressmarks and full page frames which include representations of marine life. The discussion of the images and the presses are for the sixteenth into the eighteenth century. Although a number and variety of presses that that utilized marks with fish are addressed in this article they are examples only and not necessarily complete. Furthermore, the entries are expansive, that is, printers’ marks are not described in isolation but with discussions of the presses that employed them and examples of the books on which they appeared. Entries are in chronological.[6]

As noted above, the month of Adar is, if not exactly, coterminous with the astrological sign of Pisces. That sign is represented by a pair of fish swimming in opposite directions, as fish swimming against the stream represents the powerful Pisces potential. They can be ‘sharks’ – charismatic, strong leaders with vision and clarity about leadership that can guide an entire nation, like Moses, who was also a Pisces. But those Pisces who prefer to go with the flow can be weak people who get carried away easily and are prone to addictive patterns of behavior.

Pisces is known for the holiday of Purim. According to the sages, it will be the only holiday to continue to be celebrated throughout the world after the Messiah comes. “When Adar begins, joy enters,” as the famous Hebraic phrase goes. It is a month of happiness, miracles and wonders. It affords us the ability to achieve mind over matter, to overcome our doubts, and connect to the Light.[7]

Another compatible view of Adar and fish states that “The astral sign of Adar is the fish (Pisces). Fish are very fertile, and for that reason are seen as a sign of blessing and fruitfulness. The Hebrew word for blessing is bracha, from the root letters bet, reish, kaff. In Jewish numerology (gematria), the letter bet has a value of 2, reish is 200 and kaff is 20. Each of these is the first plural in their number unit. What this tells us is that the Jewish concept of ‘blessing’is intertwined with fertility, represented by the fish of Adar.”[8]

Our first example of a pressmark with a fish is the most unusual in the article, the only device in which the fish is not only completely inconsistent with the above description but is the least prominent representation of a fish of all the pressmarks in the article. Among the earliest printers to make utilize of the fish in a pressmark is Joseph ben Jacob Shalit in Sabbioneta. Although the Sabbioneta press is commonly associated with Tobias ben Eliezer Foa, it was Shalit who appears to initially have been the motivating force behind the press and, with other partners, the provider of necessary financial support. Tobias Foa is credited with providing only the physical quarters, Duke Vespasian Gonzaga’s patronage, and limited financial assistance. Also associated with the press were Cornelius Adelkind, Vincenzo Conti, and R. Joshua Boaz Baruch, all prominent names in mid-sixteenth century Hebrew printing in Italy.

The first title printed at the press was Don Isaac ben Judah Abrabanel’s (1437-1508) Mirkevet ha‑Mishneh (1551), a commentary on Deuteronomy. Abrabanel began work on Mirkevet ha‑Mishneh when still in Lisbon, unlike the remainder of his commentary on the Torah which was written much later. Its completion was postponed, however, due to his responsibilities at the Portuguese court. The incomplete manuscript of Mirkevet ha-Mishneh was lost when Abrabanel was forced to flee Portugal in 1483. However, on his later peregrinations after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain Abrabanel came to the island of Corfu in 1493, where he serendipitously (miraculously) found a copy of the manuscript. Leaving aside other work he turned to completing this commentary, but after the departure of French troops from Naples, Abrabanel went to Monopoli (Apulia), where Mirkevet ha-Mishneh was finally completed in the first part of 1496.

The title page, dated 5311 Rosh Hodesh Sivan (Wednesday, May 16, 1551) is comprised of an architectural border with standing representations of the mythological Mars and Minerva. This border was first employed by Francesco Minizio Calvo in Rome in 1523 and as late as 1540 in Milan. This is its earliest appearance in a Hebrew book. It would be often reused and copied, appearing on the title pages of books printed as far apart as Salonika and Cracow.[9]

On the final unfoliated leaf are two devices, on the right that of Foa, a palm tree with a lion rampant on each side and affixed to the tree a Magen David, about it the verse, “The righteous flourish like the palm tree” (Psalms 92:13), all within a circle, and to the sides the letters ט and פ for Tobias Foa. On the left is Shalit’s device, a peacock standing on three rocks, facing left, with a fish in its beak within a cartouche, although Avraham Yaari, after describing the peacock with a fish, adds, in parenthesis, (or a worm?). The letters יביש about this device stand for Joseph ben Jacob Shalit. Also printed by the press that year was R. Isaac ben Moses Arama’s (c. 1420–1494) Ḥazut Kashah, on the relationship of philosophy and religion. It too has the Mars and Minerva title-page, but here the last leaf is foliated and has one pressmark only, the peacock with fish of Shalit.[10] Parenthetically, Arama too was a refugee from Spain.

Fig. 1 pressmarks of Joseph Shalit (left) and Tobias Foa (right)

The peacock with fish pressmark was reused by Shalit in Mantua at the press of Venturin Rufinelli with the colophon of several works, for example the late 10th century ethical work based on animal tales, translated from the encyclopedic Arabic Rasa`il ikhwan as-safa` wa khillan al-wafa` (Epistles of the Brethren of Purity and Loyal Friends) into Hebrew by Kalonymus ben Kalonymus (c. 1286-c. 1328) as Iggeret Ba’alei Hayyim (1557). The original is comprised of 52 eclectic volumes (pamphlets) on philosophy, religion, mathematics, logic, and music. The portion from which Iggeret Ba’alei Hayyim is taken appears at the end of the 25th book. The original was prepared by the Brethren of Purity, a secret Arab confraternity which flourished in Basra, Iraq in the second half of the tenth century. The tales themselves have an Indian origin. Four other varied works of note with the peacock with fish pressmark are R. Saadiah ben Joseph Gaon’s (882-942) Sefer ha-Tehiyyah ve-Sefer ha-Pedut (1556) on resurrection; R. Abraham ben Samuel ha-Levi ibn Hasdai’s (13th century) Ben ha-Melekh ve-ha-Nazir (1557), also based on an Indian romance and here derived from the Arabic; Berechiah ben Natronai ha-Nakdan’s (12th-13th century) Mishlei Shu’alim (1557-58) popular collection of fables, and a Haggadah with the Mars and Minerva title-page (1568).

The Shalit pressmark also appears on the title-page of several books printed in Venice at the press of Giovanni di Gara, without mention of Shalit, so that Yaari suggests he was not involved with the books but it was used simply as an ornament. Among the titles with this pressmark are R. David Kimhi’s (Radak, c. 1160-c.1235) commentary on Psalms (1566), R. Moses ben Baruch Almosnino’s (c.1515 – c.1580) Me’ammez Ko’ah (1587-88), R. Samuel ben Abraham Laniado’s (d. 1605) Keli Hemdah (1596), each with a biblical verse about the frame, and R. Aaron ibn Hayyim of Fez’s (1545–1632) Lev Aharon (1608), this last without the biblical verses about the cartouche. The Shalit pressmark appears in various places in the books, after the introduction, by the colophon, least often on the title-page. Yaari notes that the Shalit device was also employed by Georgi di Cavilli in an Ashkenaz rite Mahzor (1568).[11]

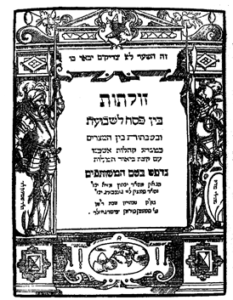

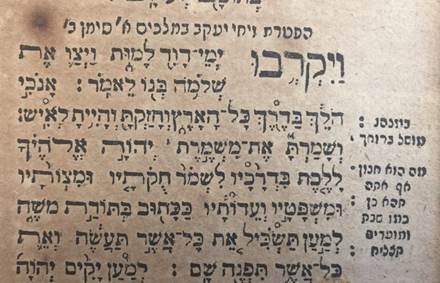

Leaving Italy, for now, and Shalit, we turn to Cracow where Isaac ben Aaron Prostitz, who together with his sons after him, printed Hebrew books for fifty years, beginning in 1569. In 1578, Prostitz printed at least three large format attractive tractates from the Talmud, Avodah Zarah, Ketubbot, and Rosh Ha-Shanah, the last extant in a ten folio unicum fragment in the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary. Moritz Steinschneider writes that Avodah Zarah was printed “si revera Supplementi tantum instar ad ed. Basil,” and “seu castrata . . .Cracoviae vero supplementi instar excusus,” that is, to compensate for its omission of the entire tractate from the much censored Basle Talmud.[12] Another feature of this tractate is that it is the first employ by Prostitz of the shield with two fish facing in opposite directions, the upper facing left, the lower facing right, above a printer’s inker, as his device.

Prostitz’s apparent next use of this device, this the first noted in bibliographic sources, is a Mahzor (1584) printed with the support of four partners, and reused frequently afterwards on such varied titles as Josippon (1589) at the end of the book, Avot with the commentary Derekh Hayyim by R. Judah Loew ben Bezalel (Maharal of Prague, c. 1525-16) after the introduction (1589), R. Moses ben Jacob Cordovero’s (Ramak, 1522-1570) Pardes Rimmonim (1591), between the books introductions, R. Bahya ben Joseph ibn Paquda’s (late 11th century) Hovot ha-Levavot, after the translator’s preface (1593) and R. Naphtali Hirsch ben Asher Altschuler’s (16th-17th cent.) Ayyalah Sheluha c. 1595. Pardes Rimmonim was actually printed in Cracow/Nowy Dwor, the change in location due to a serious outbreak of plague in Cracow, Prostitz and his family forced to flee to Nowy Dwor with the press’ typographical equipment. Pardes Rimmonim was completed in that location, the only Hebrew book printed in that Nowy Dwor.[13]

Fig. 2 Pressmark of Isaac Prostitz

Yaari questions Prostitz’s use of this pressmark. While the employ of the printer’s tool is clear, that is not the case for the fish. He suggests that it might be a propitious sign for the partners in the printing of the Mahzor in 1584, which Prostitz continued to use afterwards. This is unlikely, however, for, as we have noted, this device had been employed previously in 1578 on tractate Avodah Zarah. Another possibility is that the fish alludes to the month (Adar) in which Proztitz was born, but he then inquires why the pressmark was not used previously on all the books printed by the press. Yaari notes Steinschneider’s suggestion that the fish represented Prostitz’s entreaty for children, as his sons were borne at an old age. Here to, however, he observes that Prostitz’s four sons were born earlier, being mentioned in the colophon to Toledot Yitzhak in 1593. Another suggestion is that the fish allude to the name of R. Naphtali Hirsch ben Asher Altschuler who was known by all as Hirsch mokhir seforim (bookseller) in Lublin and for whom Prostitz printed books, for example Hovot ha-Levavot, the fish alluding to the name Naphtali, for the portion of the tribe Naphtali included the Kinneret Sea, in which fish were plentiful, but Yaari concludes this is only speculative.[14] I would question why, even if this is true for R. Altschuler, what does this have to do with Prostitiz and why he should have adopted this fish image for his pressmark?

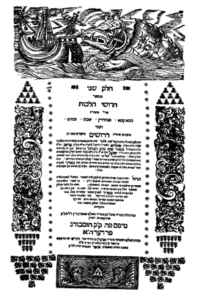

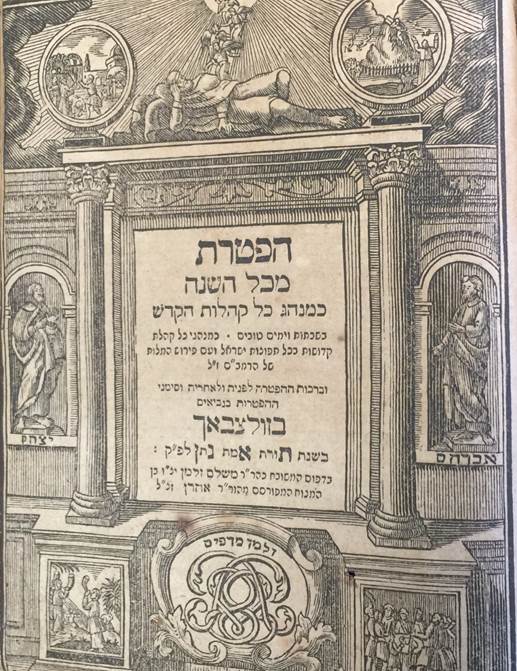

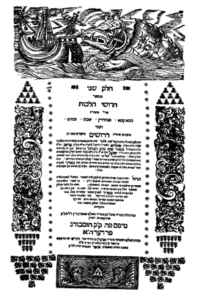

A short lived press existed in Thannhausen, Bavaria, near Augsburg, a zoltot (supplementary festival prayers for the period between Passover and Shavu’ot) and a Mahzor (c. 1594) for the entire year according to the Ashkenaz rite were printed in the last decade of the sixteenth century. The press was a furtive effort to print Hebrew books by R. Isaac Mazia, whose name, it has been suggested, is an abbreviation for mi-zera Yehudim anusim, that is, he was of Marrano origin, or that he had served as rabbi in several communities in southern Germany, together with R. Simeon ben Judah ha-Levi of Guenzburg (Simon zur Gemze) of Frankfurt, who arranged with the Munich printer Adam Berg, to issue those works. When printing the mahzor the printers, concerned about the Christian response to sensitive passages and accusations of blasphemy, left blanks to be filled in by the purchasers.

After an examination of the still incomplete mahzorim by the censor at the University of Ingolstadt the press run of 1,500 copies was destroyed; only five copies are known to be extant today. In August, 1597, Mazia was fined 200 florin and released, while Berg, as late as 1604, was still attempting to have his impounded press returned. All of this occurred despite the fact that the authorities concurred that the mahzorim had been approved for publication by the imperial authorities in Prague. Nevertheless, the printers had neither received nor sought permission from the local authorities in Burgau to print. Moreover, as the books were for export they gave the impression that printing was done with the permission of those authorities.

Fig. 3b Zoltot

Fig. 3a Zoltot Extract

Both titles have a like frame comprised of an ornamental border with three entwined fish at the top (the signet of Mazia), at the sides are armed men in armor each with a shield, the right shield engraved with the name R. [Isaac] Mazia, the left with the name R. Simeon Levi. At the bottom is a laver pouring water on two hands, representative of the [Simeon] Levi. Isaac Yudlov informs that the fish here represent Isaac Mazia; this appearance of three fish as a printer’s mark is apparently unique. [15]

Not long afterwards we find the fish image employed in Lublin at the press of Zevi bar Abraham Kalonymous Jaffe. Lublin has a long and proud history as a Hebrew printing center, beginning with the press established by the family of Hayyim Shahor (Schwarz), that is, his son Isaac and his son-in-law Joseph ben Yakar. This press, through descendants and collateral members, would be active for almost a hundred and fifty years. The presses’ began publishing in 1551, with a folio Polish rite mahzor for the entire year, continuing until 1646 when a fire forced the press to close; printing resumed in 1648 when tah-ve-tat (gezerot Polania, the Chmielnicki massacres of 1648-49), broke out. That and the 1655-60 Swedish Muscovy wars, combined with others conflicts besetting the area made it impossible for Jaffe to continue and he had to close the press. Printing did resume when Solomon Zalman Jaffe ben Jacob Kalmankes of Turobin, encouraged and supported by his father, reestablished a Hebrew press. He printed 30 books until 1685 and the entire Jaffe family is credited with as many as 180 Hebrew titles.

Fig. 4 Pressmark of Zevi Jaffe

A device employed by Zevi Jaffe, found on the title page of tractates in the large folio edition of the Babylonian Talmud published from 1617-1639, and after the introduction to R. Joel Sirkes’ (Bah, 1561–1640), Meishiv Nefesh, and possibly other works is a deer with raised forelegs, above a crown atop a shield with two fish, the upper facing left and the lower facing representative of the fact that he was a Levi, often accompanied by two fish, here too indicating that he was born in the month of Adar.

Among the many prominent printers of Hebrew books in Amsterdam is Uri Phoebus ben Aaron Witmund ha-Levi. He had previously worked for Immanuel Benveniste; in 1658, Uri Phoebus established his own print-shop. He would print about one hundred titles, from 1658 to 1689, the period he was active in Amsterdam, generally traditional works for the Jewish community, encompassing Bibles, prayer-books, halakhic works, haggadot, aggadot, and historical treatises (Yosippon). Prostitz’s first pressmark, employed in 1569 on the title-page of R. Naphtali Hertz ben Menahem of Lemberg’s Perush le-Midrash Humash Megillot Rabbah and intermittently afterwards was a stag within a cartouche. Subsequently, Uri Phoebus employed as his device a hand pouring water from a laver, representative of the fact that he was a Levi, often accompanied by two fish, here too indicating that he was born in the month of Adar.

The first usage by Uri Phoebus of this device was in 1660 on the title-page of Ketoret ha-Mizbe’ah, R. Mordecai ben Naphtali Hirsch of Kremsier’s (d. 1670) work on the aggadic portions of tractate Berakhot dealing with the destruction of the Temple and the length of the exile. The title-page of this folio book has an arabesque frame and across the lower half of the page is Uri Phoebus’s fish mark. That device would be frequently used as a decorative ornament in many of the books that Uri Phoebus printed, placed in various locations, after introductions or the colophons.

Fig. 5a Ketoret ha-Mizbe’ah

Fig. 5b Ketoret ha-Mizbe’ah Extract

Examples of the fish woodcut appears in other works, but not necessarily on the title-page, for example, in R. Hayyim ben Benjamin Ze’ev Bochner’s Or Hadash (c. 1671-75), on the laws of benedictions in a concise and abridged form, the title page of Or Hadash has an architectural frame headed by an eagle but no fish, that device being but one of several tail-pieces.

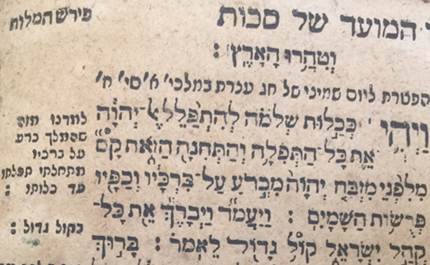

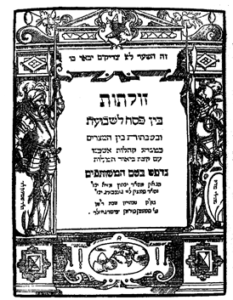

In 1662 Uri Phoebus printed an illustrated Haggadah accompanied by the commentary of R. Joseph Shalit ben Jacob Ashkenazi of Padua entitled Nimukei Yosef. The title-page of this quarto Haggadah has an architectural frame with two robed men at the sides, above winged cherubim and between them two fish with the winged head of a cherub. At the bottom are two vignettes; on the left the punishment of Shehem for the rape of Dinah and on the right the tribe of Levi killing the worshipers of the golden calf. In 1667-68, Uri Phoebus printed, also with this title-page, Nahalat Shivah (below and extract to right), R. Samuel ben David Moses ha-Levi’s (c.1625–1681) work on legal documents, particularly relating to divorce and civil matters. Nahalat Shivah has the same title-page as the Haggadah, here dated, “The Messiah ben David is coming משיח בן דוד בא (427 = 1667),” reflecting the referring to the false messiah Shabbetai Zevi. This title-page and fish crest (below) would be reused by Uri Phoebus for many years and elsewhere besides Amsterdam.

Fig. 6a Nahalat Shivah

Fig.6 Nahalat Shivah Extract

Other title-pages employed by Uri Phoebus, with different architectural frames but with a like laver and fish image include such varied works as R. Jonah ben Isaac Teomim (d. 1669) of Prague’s Kikayon di-Yonah (1669-70), novellae on tractates of the Babylonian Talmud and, attributed to R. David ben Aryeh Leib of Lida (c. 1650-96) Migdal David (1680), both with the Benveniste frame; and R. Isaac Benjamin Wolf ben Eliezer Lipman (d. c. 1698), rabbi of Landsberg, Germany’s Nahalat Binyamin (1682), the first part of a commentary on the taryag [613] mitzvot and R. Shabbetai ben Meir Ha-Kohen’s (Shakh, 1621–1662) Siftei Kohen, a commentary and halakhic novellae on Shulhan Arukh Hoshen Mishpat these with a frame with rectangular shapes, all with the fish and lave at the apex.[16] The title-page of Siftei Kohen, the first part of a commentary on the taryag [613] mitzvot dates the beginning of the work to 21 Tammuz, days of the Messiah ימי המשיח (423 = Thursday, July 26, 1663). The colophon dates completion of the work to Monday, 21 Heshvan, in the days of the Messiah בימי המשיח (425 = November 9, 1664, actually a Sunday), both dates (Messiah) a possible allusion to Shabbbtai Zevi.[17]

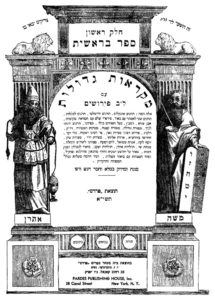

Among the more elaborate title-pages is that of the first complete translation of the Bible (1676-78) into Yiddish by R. Jekuthiel ben Isaac Blitz, a rabbi from Witmund, Germany and corrector at the press of Uri Phoebus. This edition was the subject of a serious controversy with the Amsterdam printer Joseph Athias, who published an almost simultaneous and related Yiddish edition by Joseph Witzenhausen printed (Amsterdam, 1679-87).

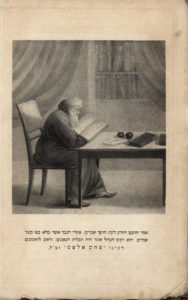

Fig. 7a Bible – Engraved Front-piece

Fig. 7b Later Prophets

Figs. 7c, 7d Extracts

The Bible has an engraved front-piece title-page with depictions of Moses and Aaron, Mount Sinai at the top, and in the lower right hand corner a coronet and below it the raised hands of the Kohen giving a benediction. In the lower left hand corner is a fish and laver image, here the two fish are crisscrossed. The engraved title page is incorrectly dated תזל כטל (439 = 1679), whereas the like title-pages for each of the biblical divisions are correctly dated תלז(437 = 1677), such as Later Prophets, below. The text has a separate but like title-page for Former Prophets, Later Prophets, and Writings. Note that in the otherwise like depictions of the fish and laver the position of the laver and water is reversed.

In 1689, Uri Phoebus ceased printing in Amsterdam, in order to relocate to Poland. Faced with competition from the large number of Hebrew printers in Amsterdam, Uri Phoebus felt that he would be more successful in Poland, located closer to its large Jewish population, a major market for the Hebrew printing-houses of Amsterdam. He established the first Hebrew press in Zolkiew in 1691, bringing his typographical material with him. Uri Phoebus’ descendants continued to operate Hebrew printing-presses in Poland into the twentieth century.

One of, if not the first book printed by Uri Phoebus in Zolkiew is R. Mordecai ben Moses Katz of Prostitz’s Derekh Yam ha-Talmud (1692) a super-commentary on the Hiddushei Halakhot of R. Samuel Eliezer ben Judah ha-Levi Edels (Maharsha). The title-page of this small work (40: 8ff.), much worn, appears to be the Benveniste frame, but at the apex is the same fish image as at the apex of Siftei Kohen. Among the decorative material, after the introduction and after the colophon is Uri Phoebus’ four fish mark, one on each side facing a laver from which water is being poured.

Among the other works published by Uri Phoebus in Zolkiew with the Nahalat Shivah title page reproduced above, is R. Jekuthiel ben Solomon Zalman ha-Levi Suesskind’s Dat Yekuthiel (1696,), a concise (80: 16 ff.) versified enumeration of the taryag mitzvoth (613 commandments). After the approbations to Dat Yekuthiel, there are thirteen, is the press mark comprised of four fish and laver. The title-page informs that the manuscript was found by Jekuthiel’s son Jonah of Kalish in his father’s bag, and arranged and brought to press by his grandson Menahem Feibush.

After the approbations is a letter from Jekuthiel to his son Eliezer. Jekuthiel, who was incarcerated at the time, in which he writes from his dark cell of his painful existence, where he had “wormwood, and gall to drink” (cf. Jeremiah 9:14) until “‘My soul is weary of my life’ (Job 10:1) ‘and my soul became impatient’ (Zechariah 11:8) to die in this way with this ‘light bread’ (Numbers 21:5) that I eat, absorbed in all my limbs, ‘the bread of adversity, and the water of affliction’” (Isaiah 30:20). Jekuthiel continues, describing his hardships, and then writes, “I will pay my vows to the Lord” (Psalms 116:14, 18) and that he took “of that which came to my hand a (new) offering” (cf. Genesis 32:14) on the taryag mitzvot. He thought to write on them in verse, “parallel, one with the other” (Exodus 26:17, 36:22), in single stanzas to the end, in the order of the Torah with references to the Hamishah Homshei Torah in the margins. Jekuthiel tells his son to take this as his blessing, which will be for a remembrance for both of them.

Uri Phoebus passed away in c. 1705.[18] He was succeeded in Zolkiew by his son Hayyim David, who had assisted his father at the press. Unfortunately, Hayyim David died shortly after his father, leaving the print-shop, in turn, to his sons, Aaron and Gershon. Uri Phoebus’ descendants continued to operate Hebrew printing-presses in Poland into the twentieth century. Aaron and Gershon did not use the ornamental material brought by Uri Phoebus to Zolkiew, instead preparing new frames that also reflected that they were Levi’im, and employed on such small format books as R. Raphael Lonzano’s Kinyan Avraham (1723) and R. Meir ben Levi’s Likkutei Shoshanim (1727). This ornate frame continued to be used by their descendants, among them Judah Solomon Yarsh Rappaport in Lvov on a Shir ha-Shirim with the commentary Magishi Minhah (1817) in Lvov.[19]

Fig. 8a Kinyan Avraham

Fig. 8b Kinyan Avraham Extract

Turning to, Germany, we find two fish, here facing in the same direction, on a title-page with an architectural pillared title-page, and at the bottom a palm tree, about it on the left a crab facing right and on the right two fish, both facing left, the former the sign of Tammuz (Cancer, scorpio), and, as already well noted, the latter the sign of Adar. The two zodiacal emblems may have had a personal significance, but, as Yosef Hayyim Yerushalmi observes describing a slightly later usage “the significance of this combination is difficult to ascertain.[20]

First employed in Fuerth by Joseph ben Solomon Zalman Schneur and his sons from 1691 through 1698, beginning with Torat Kohanim, and other folio volumes, primarily from the Shulhan Arukh, a like frame was subsequently used by Aaron ben Uri Lippman Frankel beginning with a Haggadah, in Sulzbach (below). Aaron was active in Sulzbach from the mid-1690’s until he passed away in 1720 at the age of seventy-five, first utilizing the fish image on a Mahzor printed in 1699 and afterwards in his folio imprints. Among those titles is a Haggadah (1711) with an attractive engraved copperplate front-piece (but without fish) followed by the second architectural pillared title-page described above. The architectural title-page was subsequently reused in Feurth by Hayyim ben Zevi Hirsch, who is credited with printing as many as 164 titles in that location, among the works with this frame and fish mark are several Haggadot (1746, 1752, and 1756).[21]

Fig. 9a Aaron ben Uri Lippman Frankel

Fig. 9b Aaron ben Uri Lippman Frankel Extract

The site of yet another press that employed fish on the title-page, here apparently once only, was in Wandsbeck, a borough in north-west Hamburg in Schleswig-Holstein. The first printed books in Wandsbeck are dated to the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, beginning with the Astronomiae instauratae Mechanica of Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), the famous Danish astronomer, published in 1598 by the printer Phillip van Ohr. Hebrew printing in Wandsbeck is a later occurrence, beginning approximately a century after its non-Jewish counterparts. It flourished for a brief period, primarily, albeit not solely, at the press of Israel ben Abraham.[22] The Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book enumerates forty-four titles from 1688 through 1744, several of which, including the titles previous to Israel’s sojourn in Wandsbeck, are listed as doubtful and includes duplicates as well.[23]

Israel ben Abraham was a proselyte who, reputedly, had previously been a Catholic priest. After his conversion Israel eschewed the sobriquets common among converts such as Avinu or the Ger (convert). Israel converted to Judaism in Amsterdam, where he wrote a Yiddish-Hebrew grammar Mafte’ach Leshon ha-Kodesh (Amsterdam, 1713). In 1716, after leaving Amsterdam, Israel ben Abraham acquired the typographical equipment belonging to Moses Benjamin Wulff, the court Jew in Dessau, and printed in Koethen, Jessnitz, and then in Wandsbeck from 1726-33, returning, after a brief retirement, to Jessnitz in 1739, printing a small number of titles to 1744.

Fig. 10a Selihot with ma’ariv be-zemanah

Fig. 10b Selihot with ma’ariv be-zemanah Extract

Selihot with ma’ariv be-zemanah (evening prayers in its time) is one of if not the first dated book attributed to Israel ben Abraham in Wandsbeck; it is a small octavo book (80: 7, 9, [4], 10-13, 13-23, [3] ff.). Its distinct title-page states that it is a Selihot with ma’ariv be-zemanah and that it contains matter pertaining to women; it informs that it was printed “as vowed and accepted upon themselves by the men of the hevra kaddisha (burial society) of the gemilut hasadim (charitable association) of HALBERSTADT,” and that it was “brought to press by the heads, the officers of the hevra kaddisha, R. Wulff and the noble R. Leib Warburg.” The title-page is dated in the year “You resuscitate the dead מחיה מתים אתה (469 = 1709),” a misdate, as noted by Moritz Steinschneider, who rejects the 1709 date (non admittunt; recusus ergo . . .) and dates it to 1730?[24] At the bottom of the title-page are images of a lion at the left supporting a signet enclosing a pail, at the right a wolf supporting on the right side of the signet, two vertical fish, facing in different directions. The symbolism of these images is not clear, although it might be related to Wulff and Warburg, prominent contemporary family names.

The most dramatic, eye catching title-page with a fish motif was printed in Bad Homburg vor der Höhe at the press of Aaron ben Zevi Hirsch of Dessau. This Homburg is the district town of the Hochtaunuskreis, Hesse, Germany, on the southern slope of the Taunus, bordering, among others, Frankfurt am Main and Oberursel.[25] The title-page appears on successive editions of R. Meir ben Jacob ha-Kohen Schiff’s (Maharam Schiff, 1605-41, var. 1608-44) Hiddushei Halakhot, novellae on tractates of the Talmud, printed in Homburg in 1737, 1741, and 1747. Maharam Schiff, scion of a distinguished rabbinic family, a prodigy, was appointed rabbi of the important city of Fulda at the age of 17, where he was also served as a Rosh Yeshivah. There is a tradition that he was appointed rabbi of Prague in 1641, but if, as his grandson, who brought his works to press, reports, that he lived only 36 years, Maharam Schiff must have passed away immediately after his appointment. Maharam Schiff’s novellae are highly regarded and are reprinted in standard editions of the Talmud.[26]

The title-page has a four part frame, the top image of a fish (sea creature) attacking a ship and within the fish two men, apparently roasting a small fish (?). Below the fish (sea creature) appears to be the face of a man. On the other editions the other portions of the frame are varied. A. M. Habermann, in his work on Hebrew title-pages describes the top portion of the frame as mythological.[27]

Fig. 11 1741, Hiddushei Halakhot

Returning to Amsterdam, an edition of Avot de-Rabbi Nathan with the commentary Ahavat Hesed (1777) by R. Abraham ben Samuel Witmond (1696-1773), also the author of novellae on the Pentateuch and Babylonian Talmud (1734). Avot de-Rabbi Nathan is one of the minor tractates, fourteen (fifteen, depending upon the enumeration) minor non-canonical tractates of the Talmud today appended to Seder Nezikin. It is an ethical work, considered a supplement to or a further development of Avot but with much aggadic material not related to the Mishnah, suggestive of an aggadic midrash. Ahavat Hesed was published posthumously by Witmond’s son-in-law and grandson at the press of Gerard Johann Janson. The header and place of publication on the title-page are printed in an oversized font in red letters. At the bottom of the page is a pressmark

Fig. 12a Ahavat Hesed

Fig. 12b Ahavat Hesed Extract

At the bottom of the title-page is a shield with topped by a coronet and within it on the right are two fish facing in opposite directions, above them the sun, moon, and a star, and above them the phrase “and (Samson) said, [O Lord God,] remember me, I pray you, and strengthen me” (Judges 16:28); on the left a hand holding a pail above water, again above the sun, moon, and a star, and above the phrase “And David blessed the Lord” (I Chronicles 29:10). Yaari informs that the two phrases, allude to Witmond’s son-in-law, R. David, son of the late Solomon Bloch, together with the author’s grandson, Samson ben Moses, who brought the book to press. Furthermore, the fish refer to Samson ben Moses, born in the month of Adar, the sign of which is a fish, and the pail refers to his son-in-law David, born in the month of Shevat, that month’s sign being a pail.[28]

The fish image, replete with its symbolism of fertility and good fortune, continued to be used in Jewish imagery and pressmarks. Indeed, shortly after its appearance on Ahavat Hesed it was again employed, if only occasionally, on the title-page of works from another Amsterdam printer, this into the nineteenth century. The usage over centuries depicted here attest to the popularity and power of the fish image, persisting to the present.

[1] Joseph Lowin, “Hebrew Root Word [D-Y-G]” Jewish Heritage on Line Magazine, http://www.jhom.com/topics/fish/lowin.html.

[2] Ellen Frankel and Betsy Platkin Teutsch, The Encyclopedia of Jewish Symbols) Northvale, London, 1995), p. 55.

[3] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Salmons_in_heraldry

[4] W. Roberts, Printers’ Marks. A Chapter in the History of Typography, (London, 1893), pp. 201-02.

[5] Previous articles in this series are “Mirror-image Monograms as Printers’ Devices on the Title Pages of Hebrew Books Printed in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” Printing History 40 (Rochester, N. Y., 2000), pp. 2-11, reprinted in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2008), pp. 33-43; “The Cover Design, ‘The Printer’s Mark of Marc Antonio Giustiniani and the Printing Houses that Utilized It,’” Library Quarterly, 71:3 (Chicago, July, 2001), pp. 383-89, reprinted in Studies, pp. 44-53; “Mars and Minerva on the Hebrew Title Page,” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 98:3 (New York, N. Y., 2004), pp. 269-92, reprinted in Studies, pp. 1-17; “The Bear Motif on Eighteenth Century Hebrew Books” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 102:3 (New York, N. Y., 2008), pp. 341-61, reprinted in Further Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 57-76; “Akedat Yitzhak (the Binding of Isaac) on the Title-Pages of Early Hebrew Books,” in Further Studies, pp. 35-56; “The Eagle Motif on 16th and 17th Century Hebrew Books,” Printing History, NS 17 (Syracuse, 2015), pp. 16-40; “The Lion Motif on Early Hebrew Title-Pages and Pressmarks,” (Printing History, NS 22, (Syracuse, 2015), pp. 53-71.

[6] Among the primary sources for this article are my The Sixteenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus (Brill, Leiden, 2004) and my The Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus. Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2011, and Avraham Yaari, Hebrew Printers’ Marks From the Beginning of Hebrew Printing to the End of the 19th Century, (Jerusalem, 1943), Hebrew with English introduction.

[7] Kabbalah Centre, https://livingwisdom.kabbalah.com/pisces-adar.

[8] Aish.com, http://www.aish.com/h/pur/b/The_Choice_of_Adar.html.

[9] Concerning the widespread use of this frame see my “Mars and Minerva on the Hebrew Title Page,” noted above.

[10] Yaari, Hebrew Printers’ Marks, pp. 12, 132 no. 19.

[11] Yaari, p. 132.

[12] Moritz Steinschneider, Catalogus Liborium Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (Berlin, 1852-60), col. 220 n. 1407, col. 228 n. 1427.

[13] Nowy Dwor, Polish for ‘new manor’, is the prefix of several locations with that title. Another Nowy Dwor, Nowy Dwor Mazowiecki, was home to a Hebrew press in the late eighteenth – early nineteenth centuries, printing a significant number of Hebrew titles from 1781 through 1818.

[14] Yaari, pp. 26, 139 no. 42.

[15] A. M. Haberman, Title Pages of Hebrew Books (Safed, 1969), pp.m 48,129 no. 34; Isaac Yudlov, Hebrew Printers’ Marks: Fifty-Four Emblems and Marks if Hebrew Printers and Authors (Jeruslaem, 2001), pp. 36-40 [Hebrew]. He also informs that three small fish are the mark of the Gronim family of Prague in the sixteenth century, appearing on their headstones.

[16] Concerning Lida and Migdal David see my“David ben Aryeh Leib of Lida and his Migdal David: Accusations of Plagiarism in Eighteenth Century Amsterdam,” Shofar 19:2 (West Lafayette, Ind., 2001), pp. 117-28, reprinted in Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book, pp. 191-205.

[17] Another work refering to Shabbetai Zevi noted by Ch. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography of the following Cities in Europe: Amsterdam, Antwerp, Avignon, Basle, Carlsruhe, Cleve, Coethen, Constance, Dessau, Deyhernfurt, Halle, Isny, Jessnitz, Leyden, London, Metz, Strasbourg, Thiengen, Vienna, Zurich. From its beginning in the year 1516 (Antwerp, 1937), p. 29 [Hebrew] published by Uri Phoebus is Tikkun Keria with a depiction of Shabbetai Zevi “sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up” (Isaiah 6:1).

[18] Ch. B. Friedberg, History of Hebrew Typography in Poland from the beginning of the year 1534, and its development up to our days . . . Second Edition, Enlarged, improved and revised from the sources (Tel Aviv, 1950), p. 64 [Hebrew] and Yaari, p. 158, date Uri Phoebus death to 1705. L. Fuks and R. G. In contrast, Fuks-Mansfeld, Hebrew Typography in the Northern Netherlands 1585 – 1815, II (Leiden, 1984), p. 242, writes that although Uri Phoebus was very productive in Zolkiew, he returned to Amsterdam in 1705, where, in 1710, he wrote “a short history of the first settlement of the Sephardic Jews in Amsterdam,” and where he died on 23 Shevat 5475 (17 January, 1715).

[19] Yaari, p. 158.

[20] Yosef Hayyim Yerushalmi, Haggadah and History, A Panorama in Facsimiles of Five Centuries of the Printed Haggadah from the Collections of Harvard University and the Jewish Theological Society of America, (Philadelphia, 1976), plates 64, 65.

[21] Yeshayahu Vinograd, Thesaurus of the Hebrew Book. Listing of Books Printed in Hebrew Letters Since the Beginning of Printing circa 1469 through 1863 I (Jerusalem, 1993-95), I, p. 450 [Hebrew]; Yaari, pp. 51, 152-52 no, 82; Yudlov, pp. 59-61

[22] Concerning Hebrew printing in Wandsbeck see Marvin J. Heller, “Israel ben Abraham, his Hebrew Printing-Press in Wandsbeck, and the Books he Published,” Further Studies in the Making of the Early Hebrew Book (Brill, Leiden/Boston, 2013), pp. 169-93.

[23] Vinograd, II, pp. 168-69.

[24] Steinschneider, cols. 2792-93 no. 7517, 446-47 no. 2939.

[25] Concerning Hebrew printing in Homburg see my “Early Hebrew Printing in Bad Homburg vor der Höhe,” in progress.

[26] Itzhak Alfassi, “Schiff, Meir ben Jacob Ha-Kohen,” Encyclopaedia Judaica, (Detroit, 2007) vol. 18, p. 131; Mordechai Margalioth, ed. Encyclopedia of Great Men in Israel IV (Tel Aviv, 1986), col. 1028-29 [Hebrew].

[27] A. M. Habermann, Title Pages of Hebrew Books (Tel Aviv, 1969), pp. 104, 134 no. 88 [Hebrew].

[28] Marvin J. Heller, Printing the Talmud: A History of the Printed Editions of the Talmud from the mid-17th Century to the end of the 18th Century and the Presses that published them (Brill: forthcoming); Yaari, Hebrew Printers’ Marks, pp. 89, 169-70 no. 145.