Rabbi Joseph Hertz, Women and Mitzvot, Antoninus, the New RCA Siddur, and Rabbis who Apostatized, Part 1

Rabbi Joseph Hertz, Women and Mitzvot, Antoninus, the New RCA Siddur, and Rabbis who Apostatized, Part 1

Marc B. Shapiro

1. In my last post here, in discussing R. Joseph Hertz’s suggested alternative text for Maoz Tzur, I wrote that this suggestion “was simply made up by Hertz or perhaps suggested by an unnamed collaborator on his siddur commentary.” At least one person wondered if I had anything in mind when I wrote about “an unnamed collaborator.” Indeed, these words were chosen deliberately. I do not know anything specifically about collaborators on the siddur commentary. However, we do know about the collaborators on his famous Torah commentary. This Chumash used to be found in every Modern Orthodox synagogue, and now, just like the Birnbaum siddur, it is missing from most of these synagogues.[1]

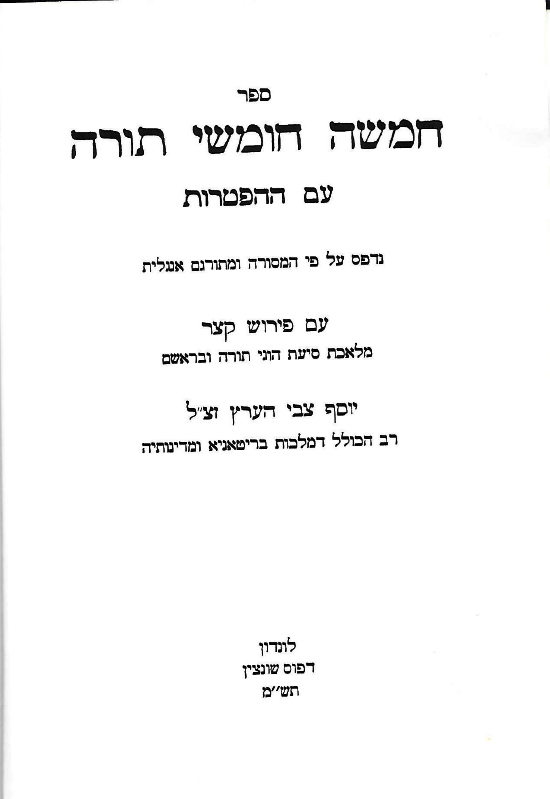

When it comes to what I will describe about the Hertz Chumash, it is possible that we are dealing with a great injustice. At the very least, it was a great misunderstanding between Hertz and his collaborators. Here are the Hebrew and English title pages of the Hertz Chumash.

The English title page refers to the Chumash as edited by Hertz. The Hebrew title page, which most people don’t even bother looking at, even if they understand Hebrew, refers to a commentary that is the work of a group of Torah scholars headed by Hertz. These are quite different formulations.

Most people who have used the Hertz Chumash, even those who have used it for many years, will not know anything about this group of Torah scholars. Indeed, when people quote from this Chumash, Hertz is given exclusive credit for everything in it. Thus, when citing this Chumash’s commentary, people will say, “Hertz writes.” Yet is this correct?

If we turn to the Chumash’s preface, we learn that Hertz was assisted by J. Abelson, A. Cohen, G. Friedlander and S. Frampton. The first three individuals prepared the commentary to sections of the Torah (the exact sections are listed), and Frampton prepared the commentary to the Haftorahs. Hertz writes: “In placing their respective manuscripts at my disposal, they allowed me the widest editorial discretion. I have condensed or enlarged, re-cast or re-written at will, myself supplying the Additional Notes as well as nearly all the introductory and concluding comments to the various sections.” We see from this that Hertz had an important role, not just as editor, but in contributing content to the Chumash. Yet the commentary itself was not the product of Hertz. He was simply the editor of the material provided by the men mentioned above. In this role, he performed the regular task of an editor who takes texts and condenses and enlarges, re-casts or re-writes, but this editorial involvement does not make the editor the author.

We therefore have to wonder why it is that the men who labored so hard in creating the commentary are given no recognition, apart from the mention of their names in the preface which virtually no one bothers to read. As I already noted, the commentary to the Chumash is universally understood to have been written by Hertz when in fact most of it – other than the “introductory and concluding comments to the various sections” – is not his at all.

Now that the facts have been laid out, I don’t think anyone will be surprised to learn that Abelson, Cohen, and Frampton were not at all happy when the Chumash appeared and they were given no recognition for their labors on the title page. (Friedlander was no longer alive.) They thought that on the title page, following the mention of Hertz as the editor, it should have said something like, “With the collaboration of the Revs. Dr. A. Cohen, Dr. J. Abelson, the Rev. S. Frampton and the late Rev. G. Friedlander.” Hertz responded to their complaint that it had already been established at the initial stages of the planning of the Chumash that the contributors’ names would not appear on the title page.[2] In fact, this a major reason for R. Salis Daiches[3] withdrawing from collaboration on the project. (Obviously, Abelson, Cohen, and Frampton had a different understanding of how Hertz was supposed to acknowledge their work.) Daiches was also unhappy with Hertz’s “editorial policy of extensively rewriting and revising the installments submitted to him by the various annotators.”[4] Hertz later implausibly claimed that his revisions were “an incredible amount of labor, easily ten times the amount of my collaborators.”[5]

Another matter that must be noted is that in the preface found in the first volume of the first edition of the Chumash—it originally appeared in five volumes—Hertz writes that he supplied “nearly all the Additional Notes.” Yet in the one volume edition this sentence has been changed and the word “nearly” has been deleted, making Hertz the only author. Harvey Meirovich has called attention to this, and shows that the Notes dealing with evolution and sacrifices came from R. Isidore Epstein.[6]

I do not know why the following paragraph, which explains the method of the commentary and appeared in the preface to volume 1 of the first edition, was deleted from the preface of the one volume Chumash. This is exactly the sort of explanation of the commentary that the reader would find helpful.

Method of Interpretation: A word must be added as to the method chosen for leading the reader into what the Jewish Mystics called the Garden of Scriptural Truth. The exposition of the plain, natural sense of the Sacred Text must remain the first and foremost aim in a Jewish commentary. But this is not its only purpose and function. The greatest care must be taken not to lose sight of the allegorical teaching and larger meaning of the Scriptural narrative; of its application to the everyday problems of human existence; as well as of its eternal power in the life of Israel and Humanity. In this way alone can the commentator hope not merely to increase the knowledge of the reader, but to deepen his Faith in God, the Torah and Israel.

Also of interest is that the first edition of the Hertz Chumash includes maps which are not found in the one volume edition.

2. In my post here I mentioned that R. Shmuel Wosner defends the practice of women saying שלא עשני גוי and שלא עשני עבד instead of substituting the words גויה and שפחה. R. Yehudah Tesner agrees with R. Wosner and adds the following: If a woman would say שלא עשני גויה this would only mean that she does not want to be a non-Jewish woman. However, she might still prefer to be a non-Jewish man instead of a Jewish woman. Also, if she said שפחה it might only mean that she does not want to be a female maidservant, as this has two negative things, namely, that she is both a woman and enslaved.

שאין רצונה להיות שפחה, שיש בזה תרתי לריעותא, גם אשה וגם משעובדת

However, it might imply that if she could get rid of one of these negative things, i.e., the female, and be a male slave, that this might be acceptable to her. In order to prevent these misunderstandings, R. Tesner says that she must keep the standard text which includes women as part of גוי and עבד. This way she is thanking God that she is not a non-Jew, male or female, and that she is not a slave, male or female.[7]

There is no question in my mind that R. Tesner’s approach is somewhat convoluted and would never represent the thinking of any woman who recited the prayer. I only mention it because R. Tesner takes it for granted that it is better to be born as a Jewish man than a Jewish woman. Yet he also sees as obvious that it is still better to be a free Jewish woman than a male slave.

With regard to this latter point, it is of interest that R. Joseph Teomim states that there are a few things in which a male slave has an advantage over a woman:

עבד חשוב לענין קצת דברים . . . במקצת דברים עדיף מאשה

One of the things he mentions is that a male slave is circumcised, and circumcision is a great mitzvah given to men that women do not have the opportunity to fulfill.[8] This perspective is obviously very different than the outlook advocated by various kiruv speakers that while women are created perfect, men are created defective and thus need a berit milah to get them up to the level of women.[9] I have no doubt that if this argument was first made by someone who identified with Open Orthodoxy, that it would have been regarded as blasphemous for denigrating the commandment of circumcision.

Regarding women not having the opportunity to fulfill the great mitzvah of circumcision (and other mitzvot), I was surprised to find that R. Leon Modena, who was quite “modern” for his time, explains that this is because they do not rank very high in God’s eyes, which is another way of saying that women are simply unworthy of these mitzvot. Here are his misogynistic words:[10]

ומצינו שלא החשיב השי”ת בתורתו הנשים בשום אופן, ולא נתן להן אפי’ אות ברית במילה, ולא רוב מצוות עשה.

Apart from circumcision, it is a popular kiruv perspective that in general women are created with more spiritual perfection, and thus do not need all the mitzvot of men. R. Meir Mazuz attacks this position which he sees as absurd.[11]

דוגמא אחת מהסילופים: המקשים מצביעים על ברכת “שלא עשני אשה”, והמתרצים מתפלפלים להוכיח שהאשה איננה צריכה כל כך סייגים וגדרים, כי מטבעה דיה במספר מועט של מצוות, ולכן היא מברכת בשמחה רבה “שעשני כרצונו” – שהקב”ה ברא אותה תמימה ושלימה שאיננה צריכה כל כך מצוות, והאיש מברך “שלא עשני אשה” – הוא על דרך שמברכין על הרעה כשם שמברכין על הטובה . . . [ellipses in original] ואילו היה כדבריהם, למה מברכין הנשים ברכת “שעשני כרצונו” בלי שם ומלכות . . . והאנשים מברכים “שלא עשני אשה” בשם ומלכות, ואדרבא איפכא מסתברא?! ובטור א”ח (סימן מ”ו) כתב שנהגו הנשים לברך שעשני כרצונו, ואפשר שנהגו כן כמי שמצדיק עליו את הדין על הרעה . . . ולדעת המתרצים הנ”ל אפשר לומר ג”כ שהגוים עדיפי מישראל, שאינם צריכים לתרי”ג מצוות רק לשבע דוקא, אתמהה.

To R. Mazuz’s words I would only add that if people find it problematic to say that men are created more perfect than women, why do they not find it also problematic to say that women are created more perfect than men? Should I have been offended when a woman once said to me that she is exempt from a number of mitzvot because women are on a higher spiritual level than men, as they are naturally more connected to God, while men can only achieve this connection through mitzvot? I am sure she would have been offended if someone said to her that women are on a lower spiritual level than men, as they are naturally less connected to God, and the evidence of this is that do not have as many mitzvot as men.[12] And what about Torah study? Can we say that men are only commanded to study Torah because they are not at the same spiritual level as women? This would be a complete inversion of the value traditionally assigned to Torah study.[13]

Yisrael Ben Reuven’s book, Male and Female He Created Them (Southfield, 1995), devotes a good deal of discussion to the kiruv perspective. On pp. 132, 133, he writes:

A number of recent books in English propose this idea of women’s spiritual superiority over men, and reportedly, the idea is taught as well in numerous schools for women. The reader should note that none of the books in question offer a classical source for the idea, and none of several teachers of the idea have been able to supply a source when interviewed by this author and numerous individuals known by the author. . . . [T]he teaching contradicts a principle from the Gemara that commandments are placed on a person as a result of his having spirituality (as opposed to his lacking it).

I believe that Ben Reuven is correct in noting that attributing this notion to the Maharal is a mistake. Yet I disagree with his discussion of the view of R. Samson Raphael Hirsch, as Hirsch indeed suggests that women are not commanded in the positive time-bound commandments because they do not need them, for they, by nature, have “greater fervour and more faithful enthusiasm for their God-serving calling.” Contrary to Ben Reuven, doesn’t this mean that they are created with a superior innate spirituality? Men, on the other hand, according to Hirsch, can only reach their spiritual potential through the mitzvot. Hirsch includes circumcision as one of the commandments that men need because they are by nature on a lower spiritual plane then women.[14]

R. Zvi Yehudah Kook also thinks that women are inherently spiritually superior to men. The problem is that men don’t realize this. However, R. Zvi Yehudah claims that in Messianic days when men will understand the truth, they will no longer be able to able to make the blessing שלא עשני אשה, as they will see that women are superior to them.[15]

במצב העכשווי האיש יותר חזק בגופו, ומתוך כך בפרקטיקה האנושית. הוא אקטיבי יותר בכל החיים המעשיים. יש הרגשה שהוא תופס יותר מקום. הרגשה זו היא לפי המדריגה האנושית, והברכות נקבעו על פי ההרגשה האנושית היחסית. זאת התפיסה האנושית הרגילה, והברכה מתייחסת למציאות זו. משום כך אומר האיש כהרגשתו “שלא עשני אשה”, שהרי זו האמת היחסית, והאשה מברכת “שעשני כרצונו”. אך, כאמור, זו תפיסה אנושית חלקית, וההרגשה היא רק עניין יחסי של מצב עכשווי נתון, אמת נוכחית.

לעומת זאת, ההשקפה האלהית, האמת המוחלטת, אינה ענין של הרגשה חולפת, אלא האמת הנצחית מראשיתה ועד סופה. לעתיד לבוא, כאשר גם האדם יכיר את האמת, ויהיה כולו מבחינת “הטוב והמטיב”, לא יוכל לברך “שלא עשני אשה”, שהרי אז יכיר שבניינה של האשה יותר רם, יותר אלהי ופחות אנושי, ממצבו הוא.

For virtually all, the approaches suggested by Hirsch and R. Zvi Yehudah Kook in which women are created more perfect than men would have been inconceivable in pre-modern times. One possible exception, and the only exception I know of, was the sixteenth-century R. Gedaliah Ibn Yahya, author of Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah. He actually enumerates numerous ways in which women are superior to men. He also claims that women are not intellectually inferior to men, and they can thus understand all the wisdoms of the world. In the sixteenth century, this was a very radical position.[16]

Regarding women, R. Yonason Rosman called my attention to the following. The ArtScroll Chumash, p. 1086 (beginning of parashat Nitzavim) states:

On the last day of his life, Moses gathered together every member of the Jewish people, from the most exalted to the lowliest, old and young, men and women, and initiated them for the last time into the covenant of God. What was new about this covenant was the concept of ערבות responsibility for one another, under which every Jew is obligated to help others observe the Torah and to restrain them from violating it. This is why Moses began by enumerating all the different strata of people who stood before him, and why he said (v. 28) that God would not hold them responsible for sins that had been done secretly, but that they would be liable for transgressions committed openly (Or HaChaim).

According to the ArtScroll summary, R. Hayyim Ben Attar, the author of Or ha-Hayyim, states that women are obligated in ערבות. But is this really what he says? Here is his commentary to Deuteronomy 29:9:

R. Hayyim ben Attar actually says the exact opposite of what appears in the ArtScroll summary, in that he states that women are not obligated in ערבות, and they are grouped together with children and proselytes. R. Ben Attar tells us that children are not obligated because they do not have the requisite understanding for such an obligation. Proselytes are not obligated because it is not their place to be rebuking, and thus exercising authority over, those who were born Jewish.[17] Why are women not obligated? R. Ben Attar writes:

ואין הם נתפסים על אחרים שהטף אינם בני דעה והנשים כמו כן הגרים גם כן אין להם להשתרר על ישראל

The sentence is ambiguous, and it all depends on where you put the comma. Here is one way to read the sentence:

ואין הם נתפסים על אחרים שהטף אינם בני דעה והנשים כמו כן, הגרים גם כן אין להם להשתרר על ישראל

If you place the comma after the words והנשים כמו כן, the sentence seemingly means that women are just like children in not having the requisite understanding of the various sins to be obligated in ערבות. R. Yaakov Hayyim Sofer finds it incomprehensible that R. Ben Attar would say that women’s level of understanding is comparable to that of children.[18] He therefore explains that when R. Ben Attar says והנשים כמו כן, he only means to say that the law for women is like the law for children, but not that the reason is the same.

You can also place the comma after the words אינם בני דעה so that one reads the sentence this way:

ואין הם נתפסים על אחרים שהטף אינם בני דעה, והנשים כמו כן הגרים גם כן אין להם להשתרר על ישראל

Now the sentence means that children do not have the requisite understanding to be obligated in ערבות, and women are like proselytes in that it is not their place to be rebuking, and thus exercising authority over, Jewish men. Although this is how R. Avraham Sorotzkin understands the Or ha-Hayyim,[19] I find it difficult as the second half of the sentence does not read well this way.

3. In my post here I referred to Nero and Antoninus and their supposed conversions to Judaism. The Talmud, Gittin 56a, indeed states that Nero converted, and it adds that R. Meir was descended from him. Soncino’s note to the passage reads: “This story may be an echo of the legend that Nero who had committed suicide was still alive and that he would return to reign (v. JE IX, 225).” The Koren Talmud’s note, which is a translation of what appears in Steinsaltz, states that the talmudic story cannot be referring to the famous Nero: “The Roman emperor Nero was killed under strange circumstances and after his death rumors circulated that he was not actually killed but had taken refuge elsewhere.” The note continues that even though Nero is referred to in the passage in Gittin 56a as ,נירון קיסר the story actually refers to another person who was an officer in the Roman army in the campaign against Judea. This person’s name was also Nero, and since he was from the larger Caesar family, he too was called Nero Caesar. This explanation apparently first appears in Seder ha-Dorot.[20]

Graetz thought that the story of Nero converting was part of a rabbinic polemic against Christianity, while Bacher “attributed the origin of the legend to the view which considers the power of Judaism to be so great, that even its greatest enemies become converts either themselves, or, at any rate, their descendants.”[21]

Let me offer another way of explaining the story of Nero’s conversion, which I have not seen anyone else suggest. Josephus tells us that the Jews put up a wall in the Temple to prevent King Agrippa from viewing the sacrificial service. This upset both Agrippa and the Procurator, Festus, and Festus ordered that the wall be torn down. The Jews decided to go over Festus’ head and turned to Nero. Nero’s wife, Poppaea Sabina, pleaded their case, and as a favor to his wife, Nero ordered that the wall should stay.

Why would Poppaea plead the case of the Jews? Josephus tells us that she was a “God-fearer.”[22] Whatever the exact connotations of this term, which has been greatly discussed, she was clearly a sympathizer of the Jews. Josephus tells us that on another occasion she helped secure the release of some Jews who had been placed in prison in Rome. He also tells us that that Poppaea gave him many presents.[23] Could it be that originally the story about the conversion of Nero was said about his wife, and that in the hundreds of years before it was recorded in the Talmud, it was transferred to Nero himself?

As for the Emperor Antoninus, who was friends with R. Judah ha-Nasi, we do not know who this refers to as the title Antoninus was used for various emperors.[24] However, I want to call attention to a different point. In Sefer Yuhasin ha-Shalem, ed. Filipowski, p. 115, in listing the talmudic sages, R. Abraham Zacut includes a “Rabbi Antoninus”. Where does he get such a name? As he indicates, it comes from Mekhilta de-Rabbi Yishmael, and there are actually two separate references there to R. Antoninus.[25] The first reads:[26]

[א”ר אנטונינוס למלך שהוא דן על הכימה [הבימה

The second reads:[27]

…ר’ אנטונינוס אומר ג’ היו והוסיף עליהם עוד אחד והיו ד’

R. Antoninus is being cited as the source for halakhic teachings. Yet the text is corrupt, as was already pointed out by the Vilna Gaon. He emended both passages so that while Antoninus is mentioned, he is not identified as a rabbi.[28]Thus, in the first passage the Vilna Gaon emended it to read:

[אמר רבי אנטונינוס המלך שהוא דן על הכימה [הבימה

The second passage he emended to read:

רבי אומר ג’ היו הוסיף עליהם עוד אחד והיו ד’ הוסיף אנטונינוס עוד אחד והיו ה’

While the Vilna Gaon may have only sensed intuitively that the text was corrupt, manuscript evidence exists that offers versions similar to or identical with that suggested by the Vilna Gaon.[29]

As for the conversion of Antoninus, R. Solomon Judah Rapoport argues that this is a late, and non-historical, aggadah.[30] He points to a passage in the Jerusalem Talmud, Megillah 1:11, which shows that it was not clear whether Antoninus converted.

אית מילין דאמרין דאתגייר אנטונינוס ואית מילין אמרין דלא אתגייר אנטונינוס

Nevertheless, despite these words, the continuation of this talmudic passage records that he did in fact convert. This is also the conclusion in the Jerusalem Talmud, Sanhedrin 10:5. However, the matter is still not clear, since regarding the Megillah text the Leiden manuscript has a different version which leaves the matter of Antoninus’ conversion undecided.[31] Furthermore, as Shaye J. D. Cohen writes, “the Bavli clearly implies that Antoninus was not a convert, unlike the Roman dignitary Qetia who was.”[32] Cohen also calls attention to Yalkut Shimoni: Isaiah, no. 429, which states that Antoninus was one of the tzadikei umot ha-olam, that is, not a convert.

R. David Zvi Hoffmann examined the various aggadot regarding R. Judah ha-Nasi and Antoninus. With regard to most of them he concludes that they arose in Babylonia long after the events described, and that “it is difficult to find a historical core to them.”[33]He does not tell us whether he regards these stories as simply legends that arose from the people or if they should be seen as didactic tales no different than the numerous other aggadot that describe actions and dialogues of various biblical figures, matters that were also never intended to be taken as historical. R. Hoffmann also discusses how the notion of Antoninus actually converting to Judaism developed from earlier sources that only regard him as a “God fearer.”[34]

Regarding referring to people as rabbis when they do not deserve the title, such as Rabbi Antoninus, here is another interesting example that I believe was pointed out to me many years ago by Prof. Shnayer Leiman. When R. Jonathan Eybeschuetz’s Luhot Edut was reprinted in 1966, the publisher helpfully added an index of names at the back. What seems to have happened is that he went through the index putting “Ha-Rav” before all the names, and mistakenly added this title before Shabbetai Zvi’s name.

When the book was reprinted again by Copy Corner in the 1990s, they fixed this mistake and added שר”י.

It is interesting that in Solomon Zeitlin’s review of Gershom Scholem’s biography of Shabbetai Zvi, he criticizes Scholem for referring to Nathan of Gaza as “Rabbi Nathan.”[35] Had Scholem wished to defend himself from an Orthodox perspective, he could have pointed to the fact that decades after Nathan’s death (and also after Shabbetai Zvi’s death), one of the leading rabbis in Salonika, R. Solomon ben Joseph Amarillo (died 1722), refers to Nathan as הרב הקדוש מהר”ר נתן [36].אשכנזי ז”ל R. Joseph Molho (1692-1768), another leading rabbi in Salonika, refers to Nathan as הרב נתן ז”ל.[37] This positive reference to Nathan is found in R. Molho’s response to R. Solomon ben Isaac Amarillo, who also referred to Nathan this way.[38] In his famous work, Shulhan Gavoah, R. Molho refers to Nathan as follows: וכן קבלו מהרב נתן אשכנזי ז”ל המקובל האלהי.[39] I was surprised to see that in the new edition of Shulhan Gavoah (Jerusalem, 1993), this appears without any censorship, which presumably means that the editor did not know who R. Nathan Ashkenazi is. One final example: The famed R. Moses Zacuto (c. 1620-1697) refers to Nathan as הרב המופלא כמהר”ר נתן הידוע זלה”ה.[40]

Those who are interested in rabbinic history are familiar with R. Naphtali Yaakov Kohn’s nine volume Otzar ha-Gedolim. In vol. 4, p. 125, we find an entry for none other than the notorious Spanish apostate, Joshua Lorki, and his name is followed by שר”י ימ”ש.

Why is such a person included in a book of “gedolim”? The author explains that before he apostatized, he was a rabbi. (I do not believe this is correct. I have never before seen him described as a rabbi and know of no evidence to support such an assumption.) One can easily understand that even if someone was a rabbi, if he later converted, or became a Reform rabbi for that matter, including him in a book of “gedolim” is not going to sit well with many. This is so even though most of the rabbis included in the book are far from what one can consider “gedolim” in the way the term is used today.

Kohn did not print any letters or haskamot in the first four volumes of his work. These first appear in volume 5, and are from such varied figures as R. Joel Teitelbaum and the Chief Rabbis of Haifa. Kohn also includes a four-page letter from R. Yekutiel Yehudah Halberstam, the Klausenberger Rebbe. R. Halberstam saw the entry for Lorki and was very upset. He writes that just as no one would dream of including Dathan and Abiram among the great Jewish leaders, all the more so one should not include Lorki among the rabbis of Jewish history. He further asks, rhetorically, if אותו האיש ימ”ש שר”י should also be included because he was a student of R. Joshua ben Perahiah?

R. Halberstam is even upset that the book includes an entry for Lorki’s father, and unfairly wonders what type of man he must have been if his son turned out this way. (I say “unfairly” since there are many examples of pious people whose children ended up very differently.) Finally, R. Halberstam makes the following strong point to Kohn: If you are going to sayyemah shemoafter someone’s name, then it has to actually mean something. By including an entry for Lorki in the book, not only are you not blotting out his name, but you are doing the exact opposite by preserving his name for all to see.

ובאמת שאצל המומר לורקי כתב כת”ה בתר שמו ימ”ש שר”י. אבל זה לא רק להלכה אלא גם למעשה ואם אומרים ימח שמו א”כ איך חוקקים שמו להזכירו בזכרון קדוש אחרי שבע מאות שנים?

Kohn thought that it was OK to include an entry for Lorki because he was a rabbi before he apostatized. With this logic it would be OK to also study the Torah works of rabbis who later apostatized, since these works were written before their apostasy. (In part 2 of this post I will deal with rabbis who published seforim and then apostatized.)

5. In my last post here, I wrote that the new RCA siddur will come to be the standard siddur at hundreds of synagogues for decades to come. This was a reasonable conclusion to reach, since ArtScroll is no longer allowed to sell the RCA ArtScroll siddur which has become the standard at Modern Orthodox synagogues. Thus, when these synagogues need to purchase new siddurim – and these siddurim must have the prayers for the State of Israel and the IDF – they would naturally buy the new RCA siddur. Yet it seems that I was mistaken, as I did not anticipate ArtScroll’s response to its anticipated enormous loss of revenue. Here is the ad that many of you have already seen.

ArtScroll is continuing to sell the RCA siddur, minus the name “RCA” on the cover and Rabbi Saul Berman’s introductory essay. Instead of being the RCA edition, this siddur is now called the “Synagogue Edition.” This is designed to ensure that Modern Orthodox synagogues, when they need to buy new siddurim, continue purchasing the ones congregants are used to.

This move by ArtScroll is obviously a serious threat to the success of the new RCA siddur, as the typical Modern Orthodox synagogue will probably find it easier just to buy the new “Synagogue Edition.” It is going to take a lot of effort from the RCA to ensure that the new siddur becomes accepted across America, and only time will tell who will win the battle for the loyalty of the Modern Orthodox synagogues. I don’t know the details of ArtScroll’s contract with the RCA, so I can’t say if what ArtScroll has done is illegal. It certainly appears unethical.

When the original ArtScroll siddur appeared some thirty-five years ago, it immediately caught on, so much so that today it is hard to find an English-speaking Orthodox home that does not have an ArtScroll siddur. This is an enormous historical achievement. However, there was an obvious lack in that the classic ArtScroll siddur did not include the prayers for the State of Israel and the IDF. This meant that it could never be adopted as the siddur for Modern Orthodox synagogues. There were many people who were upset with ArtScroll for not including these prayers. Would it have been so difficult for ArtScroll to have included them with the note that “Some congregations recite these prayers”? In a siddur that found room to include Gott fun Avrohom at Havdalah, for the tiny population of ArtScroll siddur-users that says it, why could it not include prayers recited by many thousands every Shabbat? They could also have put these prayers in the back of the siddur, with the Yotzerot that today hardly anyone says. These steps would have made for an inclusive siddur, and there never would have been a need for the RCA ArtScroll Siddur.

We were led to believe that as a matter of principle, as dictated by ArtScroll’s gedolim, the prayers for the State of Israel and the IDF could not be included. It was thus a surprise that ArtScroll agreed to include these prayers in the RCA edition of the ArtScroll Siddur. The RCA recognized that everyone was moving over from Birnbaum to ArtScroll, and therefore it made sense to produce a Religious Zionist version of ArtScroll. How was ArtScroll able to include the religiously objectionable prayers? Obviously, the reason was money, but there was also deniability, as people could say that it wasn’t actually an ArtScroll siddur. Rather, it was an RCA siddur using the text of ArtScroll, so in this way ArtScroll wasn’t implicated as a partner in religious Zionism and its objectionable prayers.

With the publication of the new “Synagogue Edition” siddur, we now have a situation where ArtScroll itself is publishing a siddur with the prayers for the State of Israel and the IDF. In other words, ArtScroll is publishing a Religious Zionist text. This is definitely news. You can be as cynical as you wish in explaining why when it comes to making lots of money from Modern Orthodox synagogues, Daas Torah can be pushed aside, but it is significant that a so-called haredi publishing house has broken with haredi standards in such a significant way. Nevertheless, I hope that Modern Orthodox synagogues will realize that there is a great difference between the old RCA ArtScroll siddur, which is just the standard ArtScroll siddur with a few extra pages, and the new RCA Siddur which, in its ideological outlook and historical sophistication, is a siddur perfectly suited for today’s Modern Orthodox community.

6. Rabbi Pini Dunner recently publishedMavericks, Mystics and False Messiahs, and I know readers of the Seforim Blog will find it a wonderful read. If you have ever watched any of Dunner’s videos, you know that no one can tell a story like him. The figures and events he discusses (Samuel Falk, Emden-Eybeschuetz dispute, ClevesGet, Lord George Gordon, R. Yudel Rosenberg, Ignatz Timothy Trebitsch-Lincoln) are ones that are perfectly suited for his skill in this area. Readers should not go to this book looking for new discoveries of the sort that he has spoken about in some of his online lectures. Some people will have even read the published works upon which the chapters are based (e.g., Scholem, Leiman, Wasserstein). These sources are discussed in the concluding chapter which is itself fascinating, especially for those who love books. I heartily recommend the book even for those who know the original sources, because no one can bring a story to life quite like Dunner.

There is one thing, however, that I wish had been explained by Dunner. In the longest chapter of the book, dealing with the Emden-Eybeschuetz dispute, there are lengthy dialogues recorded between different people. We also read about when individuals smiled, when they gasped, when they turned pale, when their voice was shaky, when tears flowed down their cheeks, when they sat upright in bed, etc. Occasionally, we find this also in other chapters. Since all this is made up by Dunner (and with regard to the Emden-Eybeschuetz dispute could even be the beginnings of a movie storyline), it would have been helpful for some discussion as to why he decided to spice up the book this way. The most we get is that in the concluding chapter (p. 172), Dunner tells us that portions of the book “have been written in a style that has much more in common with dramatic fiction than with non-fiction history, including details of private conversations, and descriptive elements that may cause readers to wonder about their accuracy.” Yet the reader is never told why Dunner sometimes adopts this approach and at other times he sticks to the facts.

The chapter on the Emden-Eybeschuetz dispute includes as part of the story the legendary account of how R. Emden, on his deathbead, said, “Barukh haba, my revered father, barukh haba, Rabbi Yonatan.”[41] This was understood to mean that he was finally reconciled with his longtime adversary, and explains why they were buried in the same row. Unless one reads the concluding chapter of the book, which deals with the sources, the reader will have no way of knowing that there is no historical basis for this tale. It is attributed in the original source to R. Abraham Shalom Halberstam of Stropkov (1857-1940), though he presumably was repeating a tradition he had heard. The story was obviously invented to create a posthumous peace between the two great rabbis.

I realize that what I have described is part of the liberties taken by any good storyteller. However, anyone who reads the book will wonder why the Emden-Eybeschuetz chapter in particular, which freely mixes fact with fiction, is written in such a different style than the other chapters, which stick much more closely to what the evidence tells us. Dunner has shown that he can be both expert storyteller and historian, but speaking as a fellow historian, my preference would have been not to mix these genres in one book.

[1] Regarding the Hertz Chumash, see the articles by Mitchell First here, and Yosef Lindell here.

[2] See Harvey Meirovich, A Vindication of Judaism: The Polemics of the Hertz Pentateuch (New York and Jerusalem, 1998), pp. 187-189.

[3] Unlike the other contributors, Daiches was actually a rabbi (something not so common in Britain at the time). He received semikhah from the Rabbinical Seminary of Berlin as well as from his father, the great R. Israel Hayyim Daiches, R. Solomon Cohen of Vilna, and R. Ezekiel Lifshitz of Kalisz. See Hannah Holtschneider, “Salis Daiches – Towards a Portrait of a Scottish Rabbi,” Jewish Culture and History 16 (2015), p. 4. Holtschneider’s biography of Daiches will be out later this year. See here. The famous author David Daiches was his son, and his book Two Worlds (Edinburgh, 1997) has a lot about Salis Daiches. Here are some passages that I think readers will find of interest, as it speaks to the differences between what it meant to be an Orthodox rabbi in Britain a century ago vs. today.

Pp. 29-30: The electric radiator – which did, I suppose, make some difference, though memory links it only with extreme cold – could be switched on and off on the sabbath, as the electric light also could, in accordance with a decision of my father’s which differentiated his position sharply from that of my grandfather, patriarchal rabbi of an orthodox Jewish congregation in Leeds, who would have been shocked if he had known how cavalierly we treated electricity. Gas light or heat, which required the striking of a match, was another matter that was clearly prohibited. But electricity was a phenomenon unrecognized by the Talmud, and my father felt free to make his own interpretation of the nature of the act of switching on the electric light or heat. He decided that it was not technically ‘kindling a fire’, which a biblical injunction prohibits in the home on the sabbath.”

Pp. 81-82: “For years we travelled with our own meat dishes (for we could not eat off the meat dishes of a non-Jewish house) and Mother had supplies of meat sent out by post from the Edinburgh Jewish butcher. Packing a trunk full of dishes was an arduous business, and eventually Mother gave it up and we went vegetarian throughout August – which was no hardship for Mother could do marvelous things with fish (the term vegetarian in our family meant simply eating no meat but did not exclude fish). Slowly and gradually, and I am sure never consciously on my parents’ part, we relaxed a bit in the matter of diet. When she was first married Mother baked all her own bread, but ceased to do this after her illness in 1919. And on holiday one found oneself going a little further than one would have done in the city. In Edinburgh, we usually ate bread from the Jewish bakery, but occasionally we would get a loaf from a non-Jewish shop. Cakes and biscuits we regularly got from non-Jewish sources. But though Mother would buy ordinary cakes from a non-Jewish baker, she would always make her own pastry, for pastry from a gentile shop was liable to have been made with lard. On holiday, however, pastries started to creep in among the cakes bought for tea, and nobody raised the question of what they were made with.”

I am certain that Daiches is mistaken in his last sentence, and that his father confirmed with the bakery that there were no non-kosher ingredients in these pastries.

Pp. 92: “At home we always covered our heads to pray, and to say grace before and after meals, but we were never expected to keep our heads covered continually. My father wore a black skull cap when receiving members of his congregation in his study, but as the years went by he developed the habit of keeping it in his pocket throughout much of the day and diving hastily for it when the bell rang. In his father’s presence he wore it continually.”

Pp. 174, 176: The rabbi did not believe in a literal personal Messiah; he believed in historical movements, in progress, in amelioration, and in the acceleration of movement in the right direction by the actions of individuals. . . . The Messiah was not a person, but a historical ideal. God, the rabbi was in the habit of telling his congregation, works in history.”

Pp. 175-176: “The priestly benediction recited on High Festivals, when all the Cohens assembled to bless the congregation in the old biblical words of benediction, had been abolished by the rabbi in his Sunderland synagogue and he would not allow it in Edinburgh either.”

[4] Meirovich, A Vindication of Judaism, p. 31.

[5] Meirovich, A Vindication of Judaism, p. 33.

[6] Meirovich, A Vindication of Judaism, pp. 41ff.

[7] Siah Tefilah (Ofakim, 2003), p. 361.

[8] Mishbetzot Zahav, Orah Hayyim 46:4.

[9] See Excursus which will be in part 2 of this post.

[10] Magen ve-Herev, ed Simonsohn (Jerusalem, 1960), p. 47.

[11] See his derashah in R. Rephael Kadir Tsaban, Nefesh Hayah (Bnei Brak, 2007), vol. 2, pp. 269-270.

[12] See e.g, Derashot Rabbi Yehoshua Ibn Shuaib (Cracow, 1573), p. 48a:

כי נשמתן של ישראל הן קדושות יותר מן האומות ומן העבדים הכנעניים הפחותים ואפילו מן הנשים ואם הם שייכי במצות והן מזרע ישראל אין נשמתן כנשמת הזכר השייך בתור’ ובכל המצות עשה ולא תעשה.

[13] R. Shlomo Aviner, in discussing this matter, does not go so far as to say that men are obligated in Torah study because they are not at the same spiritual level of women. However, he comes close, and he is led to this approach because of his understanding of Torah study as leading to devekut, a position which is at odds with the Lithuanian perspective on Torah study. See Aviner, Bat Melekh (Jerusalem, 2013), p. 104:

שאלה: מדוע האשה, שניחנה בבינה יתרה, אינה מחוייבת בלימוד תורה?

תשובה: האיש, שאין בו בינה יתרה, דווקא הוא צריך להרבות בלימוד, אך האשה, שיש לה בינה יתרה, מבינה גם ללא הלימוד הרצוף והממושך. המהר”ל מסביר, שמי שיש לו נטיה טבעית לדבר, הוא משיגו בנקל. ללא נטיב טבעית יש צורך בעמל רב. לאשה באופן טבעי יש נטיה, שהאיש צריך לעמול עליה קשה (מהר”ל, דרוש על התורה עמ’ כז-כח). אלא, עמל לימוד התורה אינו איסוף ידיעות, בעומק הנפש, ודבקות בתורה. האיש הוא קשה עורף, מתקשה לשמוע לכן יש להכותו בגידים (שמות רבה כח ב. רש”י, שמות יט ג), בשוט השכלי של הלימוד. מי שניחן בנטיה טבעית לתורה אינו זקוק ל”גידים” כדי שתחול בו אותה תמורה פנימית, והיא מגיע אליו ביתר קלות . . . זו נטיה עמוקה באישיות האשה, לכן היא מגיעה לדבקות וקישור והתמלאות בתורה בנתיבים שונים מן האיש. האיש מגיע לדבקות זו בנתיב הלימודי, והאשה בנתיב ספיגת הדברים מן החיים.

See here from a Chabad site where we are told that “the female child inherently carries a higher degree of holiness, due to her own biological, life creating capability.” Would anyone today write the same sort of comment, but instead state that the male child has a higher degree of holiness? Faced with a situation where many people believe that women are regarded as inferior in traditional Judaism, defenders of Judaism are often led to offer apologetic answers that argue the reverse, namely, that it is actually women who are more special, spiritual, holy, etc. than men.

In my experience, men never seem to be offended when they hear this. One haredi friend explained to me that this is because the men do not believe it to be true, and thus no reason to be offended if it makes the women feel better. This is a cynical answer, but can anyone come up with a better reason? Imagine the scenario: A Shabbat meal with many guests and the father offers a devar Torah whose upshot is that men are more holy and spiritual than women. This will not go over well and the women (and some men also) will be offended. Yet if the message of the devar Torah is that women are more holy and spiritual, no one will take offense. Why not? And my more basic question is, why we can’t just say that men and women are equally holy and spiritual (albeit with different roles)? Why do people feel a need to say that one is more special than the other?

All this is in the realm of Jewish thought. However, when it comes to explaining halakhic matters in which women might be portrayed in a way that they would take offense at, here too new approaches must be offered. For example, can anyone imagine explaining to modern women why they cannot perform shechitah by telling them what R. Joseph Messas quotes from manuscript from the nineteenth-century R. Jacob Almadyoni (spelling?) of Tlemcen, Mayim Hayyim, vol. 2, Yoreh Deah no. 1?

אין להניח הנשים לשחוט ואפי’ בדיעבד ראוי להחמיר שאף המכשירין יודו האידנא שאין דעת נשי דידן מכוונות כדעת נשי דידהו. ואם על נשיהם אמרו אין חכמה לאשה אלא בפלך [יומא דף ס”ו ע”ב], קו”ח לנשי דידן

[14] See Hirsch’s commentary to Lev. 23:43, and regarding women and circumcision, see also Hirsch to Gen. 17:15. The most comprehensive discussion of Hirsch’s view of women and Judaism is found in Ephraim Chamiel, The Middle Way (Brighton, MA, 2014), vol. 2, pp. 152ff. On p. 153 he titles the section of a chapter: “Revolution: Women are Superior to Men.” Hirsch obviously opposed the notion found in R. David Abudarham that the reason women are not obligated in positive time-bound commandments is because they are “enslaved” to their husband to do his will, and if they were busy performing these commandments they could not serve him properly and this would create marital discord. See Abudarham ha-Shalem (Jerusalem, 1963), p. 25:

והטעם שנפטרו הנשים מהמצות עשה שהזמן גרמא לפי שהאשה משועבדת לבעלה לעשות צרכיו. ואם היתה מחוייבת במצות עשה שהזמן גרמא אפשר שבשעת עשיית המצוה יצוה אותה הבעל לעשות מצותו ואם תעשה מצות הבורא ותניח מצותו אוי לה מבעלה ואם תעשה מצותו ותניח מצות הבורא אוי לה מיוצרה לפיכך פטרה הבורא ממצותיו כדי להיות לה שלום עם בעלה.

The same reason is offered by R. Jacob Anatoli, Malmad ha-Talmidim (Lyck, 1866), pp. 15b-16a:

לפי שהנקיבה היא לעזר הזכר ואל אישה תשוקתה והוא ימשל בה להנהיגה ולהדריכה בדרכיו ולעשות מעשה על פיו והיותה על הדרך הזה הוא גם כן סבה שהיא פטורה מכל מצות עשה שהזמן גרמא כי אלו היתה טרודה לעשות המצות בזמן היה הבעל בלא עזר בזמנים ההם והיתה קטטה נופלת ביניהם ותסור הממשלה המכוונת שהיא לתועלתו ולתועלתה.

R. Ahron Soloveichik adopted an approach similar to that of Hirsch. He claimed that Judaism “recognizes the feminine gender as possessing an innate, unique spiritual blessing as compared with the male gender. . . [T]he woman has innate spiritual advantage as compared with men.”Logic of the Heart, Logic of the Mind(Jerusalem, 1991), p. 93.

[15] Itturei Kohanim, no. 167 (5759), 4-5; R. Aviner, Panim el Panim (Jerusalem, 2008), p. 194. Significantly, R. Zvi Yehudah’s explanation acknowledges that the blessing שלא עשני אשה implies male superiority. While this was a common understanding in pre-modern times, in recent generations this interpretation was usually rejected. Yet R. Zvi Yehudah claims that the blessing’s formulation was a concession to human feelings. Does this then mean that if a contemporary man recognizes the superiority of women, or even just that they are equal to men, that according to R. Zvi Yehudah he can stop saying this blessing?

[16] See Avraham Grossman “Ma’alot ha-Nashim ve-Adifutan be-Hibur shel R. Gedaliah Ibn Yahya,” Zion 72 (2007), pp. 37-61.

[17] R. Simhah Bunim Lieberman raises a strong objection to Or ha-Hayyim‘s position. See Bi-Shvilei Orayta al Kol Yisrael Arevim Zeh la-Zeh, p. 124:

אבל האמת דעצם דברי האור החיים צ”ע, דאטו מוכיח יש בו שררה, וכי מצאנו איסור לגר להוכיח ישראל שחטא

[18] Edut be-Yaakov, vol. 2, p. 164.

[19] See R. Avraham Sorotzkin, Rinat Yitzhak, Deut. 29:10.

[20] R. Yehiel Heilprin, Seder ha-Dorot (Bnei Brak, 2003), vol. 1, p. 251.

[21] Naomi G. Cohen, “Rabbi Meir, A Descendant of Anatolian Proselytes,” Journal of Jewish Studies 23 (1972), pp. 54-55. Cohen also provides the Graetz reference.

[22] Antiquities 20.8.11.

[23] Life of Flavius Josephus, ch. 3. See A. Andrew Das, Solving the Romans Debate (Minneapolis, 2007), pp. 77ff.; Louis H. Feldman, Jew and Gentile in the Ancient World (Princeton, 1993), p. 351.

[24] R. Maimon ben Joseph (the father of Maimonides), Iggeret ha-Nehamah, trans. Binyamin Klar (Jerusalem, 2007), p. 38, states:

וכבר אמר פעם אחת אחד ממלכי רומי – קללה תבוא על כולם, חוץ מאחד רם המעלה המובדל מהם, הוא אנטונינוס שהיה בדורו של רבנו הקדוש ע”ה.

[25] R. Yehiel Heilprin, Seder ha-Dorot, vol. 2, p. 138, has a version of the Mekhilta that reads Antigonos, and he therefore identifies a “Rabbi Antigonos”.

[26] Beshalah, hakdamah. In the edition with the Netziv’s commentary it is on p. 79.

[27] Beshalah, parashah 1. In the edition with the Netziv’s commentary it is on p. 111.

[28] Surprisingly, Abraham Joshua Heschel did not take note of the Vilna Gaon’s emendation, and cited one of the Mekhilta texts as is. See Torah min ha-Shamayim be-Aspaklaryah shel ha-Dorot (London and New York, 1962), p. 183 n. 3.

[29] See the Horovitz-Rabin edition of the Mekhilta, pp. 82, 89.

[30] See Rapoport, Erekh Milin (Prague, 1852), p. 270.

[31] See the comprehensive discussion in Shaye J. D. Cohen, “The Conversion of Antoninus,” in Peter Schäfer, ed., The Talmud Yerushalmi and Graeco-Roman Culture (Tübingen, 1978), pp. 141-171.

[32] “The Conversion of Antoninus,” pp. 164-165.

[33] “Die Aggadot von Antoninus in Midrash und Talmud,” Magazin für die Wissenschaft des Judenthums 19 (1892), p. 46.

[34] “Die Aggadot von Antoninus in Midrash und Talmud,” pp. 51-52.

[35] See Jewish Quarterly Review 49 (1958), p. 153.

[36] Penei Shlomo (Salonika, 1717), p. 43d.

[37] Ohel Yosef (Salonika, 1756), no. 14 (p. 13a).

[38] Devar Moshe (Salonika, 1750), vol. 3, no. 11 (p. 8a). The three sources just cited are mentioned by Meir Benayahu, Ha-Tenuah ha-Shabta’it be-Yavan (Jerusalem, 1978), pp. 191, 274-275.

[39] Shulhan Gavoah (Salonika, 1756), Orah Hayyim, vol. 2, Hilkhot Yom ha-Kippurim 620 (p. 68a). He also refers to Nathan this way ibid., Hilkhot Rosh ha-Shanah 584 (p. 35a).

[40] See Benayahu, Ha-Tenuah ha-Shabta’it be Yavan, p. 119. For sources regarding Zacuto, see Gershom Scholem, Mehkerei Shabtaut, ed. Yehuda Liebes (Tel Aviv, 1991), p. 528; Bezalel Naor, Post Sabbatian Sabbatianism (Spring Valley, 1999), p. 176 n. 8.

[41] The source of the story for Dunner is David Ginz, Gedulat Yehonatan, vol. 2, p. 286. Abraham Hayyim Simhah Bunim Michaelson, Ohel Avraham (Petrokov, 1911), p. 28b, also heard the story from R. Halberstam, but in his version R. Emden states simply, ברוך הבא אבא.