When Rav Kook Was the Kana’i (Zealot) and His Opponent the Melits Yosher (Advocate)

When Rav Kook Was the Kana’i (Zealot) and His Opponent the Melits Yosher (Advocate)[1]

By Bezalel Naor

In 1891, there appeared in Warsaw an anonymous work[2] entitled Hevesh Pe’er,[3] whose sole objective was to clarify for the masses the proper place on the head to don the tefillah shel rosh or head-phylactery. According to halakhah, the tefillah must be placed no lower than the hairline and no higher than the soft spot on a baby’s head (i.e. the anterior fontanelle).[4] In ancient times, there were sectarian Jews who deliberately placed the tefillah on the forehead, as attested to by the Mishnah: “If one placed it [i.e. the tefillah] on his forehead, or on his hand, this is the way of sectarianism (minut).”[5] These Jews interpreted literally the verse, “You shall bind them for a sign upon your hand, and they shall be for frontlets between your eyes.”[6] Adherents to Rabbinic Judaism are punctilious about placing the hand-phylactery on the biceps of the forearm opposite the heart,[7] and the head-phylactery above the hairline. East European Jews who placed their phylacteries on the forehead did so not out of conviction, as the Sadducees of old, but rather out of sheer ignorance of the law. The slim book (all of 24 leaves or 48 pages) was thus an elaborate educational vehicle to educate the masses how to properly observe the law.[8]

According to the approbation to Hevesh Pe’er by Rabbi Elijah David Rabinowitz-Te’omim (ADeReT) of Ponevezh, the book was published [but not authored] by his former son-in-law (presently his brother’s son-in-law), Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook of Zeimel.[9]

Wares in hand, the young rabbi of Zeimel (aged twenty-six) assumed the role of an itinerant bookseller, travelling from town to town in Lithuania. Wherever he went, he preached concerning the importance of fulfilling the commandment of tefillin. Historically, there was precedent for a rabbi promoting that specific mitsvah. In the thirteenth century, Rabbi Jacob of Coucy (author of Sefer Mitsvot Gadol or SeMaG), circulating in the communities of France and Spain, was able to turn the tide and convince Jews, hitherto lax in their observance of the commandment, to don tefillin.[10] As for an author posing as an itinerant bookseller, Rav Kook’s older contemporary, Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan of Radin, had done exactly that, thus earning himself the sobriquet Hafets Hayyim, after the book by that name that he peddled. (Hafets Hayyim tackles the problem, halakhic and otherwise, of malicious gossip.)

It is recorded that Rav Kook’s sermons had such a positive influence upon his audience that the Rebbe of Slonim, Rabbi Shmuel Weinberg, offered to support him if he would devote himself fulltime to acting as a maggid or peripatetic preacher.[11]

One would never have imagined that this halakhic work would meet with any rabbinic opposition.[12] The point it makes that wearing the head-phylactery below the hairline on the forehead invalidates the performance of the commandment, seems rather clear-cut in the sources. (In fact, but a few years earlier, in 1884, Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan in his work Mishnah Berurah had advised wearing the phylactery higher on the head, at a remove from the hairline, just to be on the safe side.)[13]

However, five years later, Rabbi Ze’ev Wolf Turbowitz of Kraz (Lithuanian, Kražiai; Yiddish, Krozh)[14] devoted the very first of his collected responsa to pummeling the anonymous work Hevesh Pe’er.[15] Rabbi Turbowitz prefaces his remarks by saying: “The intention of this author [i.e. the author of Hevesh Pe’er] is for [the sake of] heaven, but nonetheless he has spoken shabbily of the people of the Lord. May the Lord forgive him. For Israel, ‘if they are not prophets, they are the children of prophets.’”[16] Rabbi Turbowitz goes on to argue that the commandment is invalidated only if the majority of the phylactery is placed below the hairline. If, on the other hand, the majority is situated above the hairline and only a minority below, then the halakhic principle of “rubo ke-khulo” (“the majority as the whole”) applies, and the commandment is fulfilled.[17] One of the rabbi’s supposed proofs is that one must recite the blessing once again only in a case where the entire phylactery or the majority thereof has slipped down, but if only a minority of the phylactery has been displaced, with the majority still within the prescribed area, one does not recite another blessing upon readjusting the phylactery.[18]

Rav Kook (now outed as the author of Hevesh Pe’er) responded to the onslaught of Tif’eret Ziv. His lengthy rejoinder, entitled “Kelil Tif’eret,” appeared in the periodical Torah mi-Zion (Jerusalem, 1900).

Rav Kook dismantles Rabbi Turbowitz’s supposed proof from the fact that another blessing is unwarranted as long as the majority of the phylactery is still in its proper place. Rav Kook reasons that we must distinguish between the essential commandment (“‘etsem ha-mitsvah”) and the action of the commandment (“ma‘aseh ha-mitsvah”). The fact that one does not recite an additional blessing does not necessarily mean that the commandment (“‘etsem ha-mitsvah”) is still being fulfilled. What it does imply, is that the action of the commandment (“ma‘aseh ha-mitsvah”) is ongoing. The blessing addresses renewed action (“ma‘aseh ha-mitsvah”). In a case where only a minority of the phylactery has been displaced, the action required to readjust it does not warrant a blessing. “And the Turei Zahav[19] holds that since in the entire Torah, ‘rubo ke-khulo,’[20] once most of the action has been nullified, the action as a whole is nullified, but if most of the action remains, even though the commandment has been nullified, still the action exists…”[21]

As is typical for Rav Kook, he signs himself, “Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, servant to the servants of the Lord…Bausk.”[22]

Evidently, Rabbi Turbowitz was not one to take something lying down. He came back at Rav Kook with a stinging reply, integrated into Ziv Mishneh, his commentary to Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah.[23] There, in Hilkhot Tefillin (4:1), he maintains that since “rubo ke-khulo is a universal principle in the entire Torah”[24]—this applies to tefillin as well. He reiterates once again his proof from the TaZ, who ruled that the blessing is recited once again only in a scenario where the tefillin are totally displaced. He mentions the opinion of “one wise man” (“hakham ehad”) who wrote that even the slightest deviation disqualifies the mitsvah, and disagrees. According to Rabbi Turbowitz, lekhathilah (to begin with), the entire phylactery should be above the hairline with none of it extending down to the forehead, but be-di‘avad (ex post facto), if a minority of the phylactery is below the hairline, one has nonetheless fulfilled the commandment. And therefore, the anonymous sage was wrong to badmouth the masses, who are remiss in this respect, and their spiritual leaders, who look the other way and do not protest. “He spoke shabbily of the people of the Lord and will in the future be called to judgment!” After summing up rather concisely the position he took earlier in Tif’eret Ziv, Rabbi Turbowitz now lambastes Rav Kook for what he wrote in Torah mi-Zion (Jerusalem, 1900), no. 4, chap. 4, accusing Rav Kook of deliberately misquoting him.

In 1925, two disciples of Rav Kook, Rabbi Yitshak Arieli[25] and Rabbi Uri Segal Hamburger,[26] reissued Hevesh Pe’er in Jerusalem with Rav Kook’s permission.[27] Appended to the work was Rav Kook’s rebuttal “Kelil Tif’eret.” (In addition, this edition was graced by the comments of Rav Kook’s deceased father-in-law, ADeReT, and of Rav Kook’s admirers in Jerusalem: Rabbis Tsevi Pesah Frank, Ya‘akov Moshe Harlap, and Yehiel Mikhel Tukachinsky. Finally, there are the substantial “Comments upon Comments” [“He‘arot le-He‘arot”] of the editor, Rabbi Yitshak Arieli.)[28]

In 1939, Rabbi Yosef Avigdor Kesler of Rockaway (Arverne to be precise)[29] published a second collection of his deceased father-in-law, Rabbi Ze’ev Turbowitz’s numerous responsa. Whereas the first collection of Tif’eret Ziv covered only Orah Hayyim, this collection covered all four sections of Shulhan ‘Arukh.[30] In addition, it contained a supplement (Kuntres Aharon) entitled “Mele’im Ziv.” In the supplement, Rabbi Kesler published a letter from ADeReT to Rabbi Turbowitz that turned up in the latter’s papers.

ADeReT’s letter is datelined “Monday, Vayyetse, 5657 [i.e. 1896].” In the letter, ADeReT gratefully acknowledges receipt of the recently published book Tif’eret Ziv. Regretting that he is unable to send monetary payment for the book because he is presently inundated with works of various authors, ADeReT nonetheless wishes to at least offer some comment on the contents of the book.[31]

Referring to the very first responsum in Tif’eret Ziv, ADeReT rejoices that Rabbi Turbowitz sought to advocate on behalf of the Jewish People regarding the commandment of tefillin. He is especially overjoyed that Rabbi Turbowicz was not cowed, but dared to differ. ADeReT holds up as role models Rabbi Zerahyah Halevi (Ba‘al ha-Ma’or) who critiqued Rabbi Isaac Alfasi (Rif), only to be attacked himself by Rabad of Posquières; Rabad of Posquières who critiqued Maimonides; et al. Since this is the “way of Torah” (darkah shel Torah), why should he harbor any resentment toward Rabbi Turbowitz for disagreeing with him?[32] (ADeReT, though not the author of Hevesh Pe’er, had wholeheartedly endorsed it.)

The sterling character of ADeReT is best summed up in these lines:

God forbid, I am not deluded to think that truth resides with me. I wholeheartedly acknowledge the truth. I have not a thousandth part of resentment towards one who differs with me. And the opposite, I love him with all my soul when he points out to me the truth.[33]

Since Rabbi Turbowitz acted as a true talmid hakham (Torah scholar) who uninhibitedly speaks truth, ADeReT wonders why he failed to mention the name of the work he critiqued, Hevesh Pe’er. This would have provoked neither the author nor ADeReT.[34]

In this vein of truth-seeking, ADeReT proceeds to explain why the argument presented in Tif’eret Ziv failed to dissuade him from the position adopted both by him and the author of Hevesh Pe’er. Since the shi’ur or measurement of the area on the head where the phylactery is to be placed is Halakhah le-Moshe mi-Sinai (a law to Moses from Sinai), the principle of “rubo ke-kulo” is of no consequence in this regard.[35]

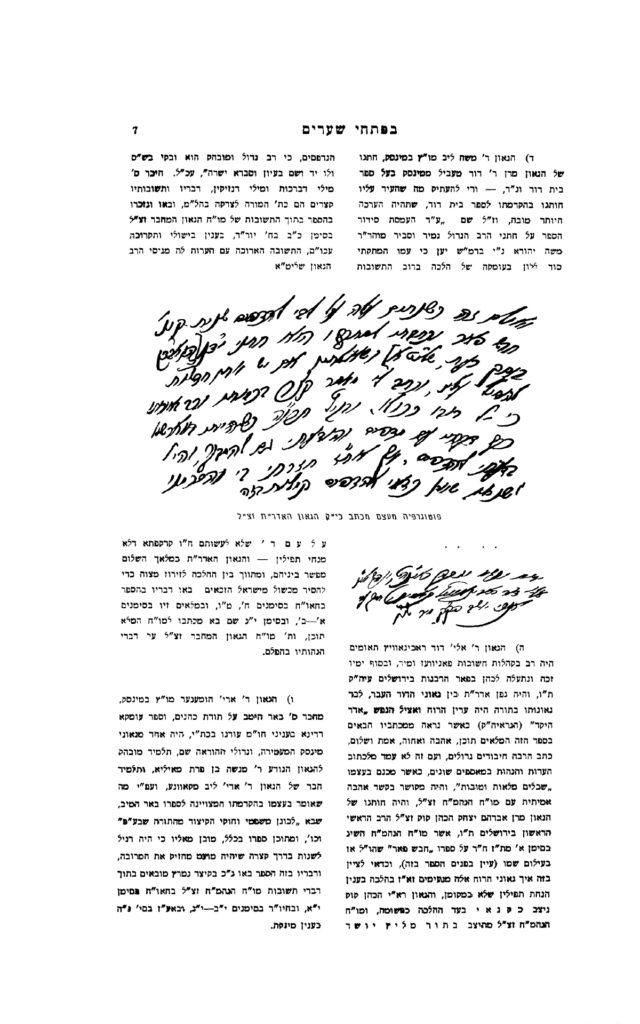

Realizing the historic importance of the contents of the letter, Rabbi Kesler provided a photograph of the crucial passage in the letter, which reads as follows:

About two years ago, the thought occurred to me to reprint the booklet Hevesh Pe’er. I wrote to its author, my son-in-law, my soul-friend (today the Rabbi of Bausk, may he live) and asked him if he has anything new to add to it. He wrote me an article, brief in quantity but great in quality, that it is possible to say ‘rubo ke-khulo.’ In the summer of 5655 [i.e. 1895] when I was in Warsaw, I already spoke with a printer and also notified the [government] censor, and I was thinking to print. But after this, I reversed myself, and the two of us [i.e. ADeReT and Rav Kook] agreed that it is not worthwhile to print leniencies (kulot) in this.[36]

ADeReT explains that if we show any leniency, it will prove a slippery slope. He reveals to Rabbi Turbowitz his unusual experience with Hasidim in particular: “From this, there came about in places where the Hasidim reside [the custom] to wear large tefillin.[37] Not one in a thousand bears most of the tefillah within the hairline. In most cases, but a small fraction (mi‘uta de-mi‘uta) [is within the hairline]. I have seen with my own eyes the entirety upon the forehead. They laughed at my rebuke, saying: ‘Thus is the mitsvah.’ ‘So we saw our fathers doing.’ etc. etc.”[38]

The letter concludes with this salutation:

His friend who is honored by his love, appreciates his genius and his Torah, and blesses him with all good,

Elijah David Rabinowitz Te’omim

…Mir[39]

[1] These are the exact words of Rabbi Joseph Avigdor Kesler in the introduction to his father-in-law Rabbi Ze’ev Wolf Turbowitz’s work of responsa, Tif’eret Ziv (Brooklyn: Moinester Publishing Company, 1939), p. 7, par. 5.

By the time of his passing in 1935, Rav Kook would be immortalized as a twentieth-century Rabbi Levi Isaac of Berdichev, the great advocate of the Jewish People, forever defending their practices in the heavenly tribunal. Today, Rav Kook is famous for his leniency concerning the Shemitah or Sabbatical year, the heter mekhirah, which allows sale of the land to a non-Jew for the duration, whereby agriculture, or at least some forms thereof, may take place. The model for this contract is the prevalent mekhirat hamets or sale of leaven to a non-Jew before Passover, so that it need not be removed from the home of the Jew.

However, in general, if one studies the teshuvot (responsa) of Rav Kook, he does not come across as extraordinarily lenient in his pesakim or halakhic decisions. Par contre, someone whose work is chock-full of startling leniencies is Rabbi Aryeh Tsevi Fromer of Kozhiglov (1884-1943), Rosh Yeshivah of Yeshivat Hakhmei Lublin and a disciple of Rabbi Abraham Bornstein (author of responsa Avnei Nezer). Rabbi Fromer designed his work of responsa, Erets Tsevi (Lublin, 1938), to be melamed zekhut, to find some halakhic justification (however farfetched) for certain otherwise anomalous practices within the Jewish community. This is apparent from the very first responsum, where the author attempts to justify the prevalent practice of wearing a tallit katan that fails to meet the prescribed shi‘ur or measurement.

[2] The title page credits as author: “KDY (Kohen Da‘ato Yafah).” The expression “kohen she-da‘ato yafah” comes out of the Mishnah, ‘Avodah Zarah 2:5. Thus, the title alludes to the author being a Kohen or member of the priestly caste.

The thought occurs to this writer (BN) that “Yafah” might be an allusion to Rav Kook’s descent from Rabbi Mordechai Yaffe (author of the Levush[im]). Rav Kook was immensely proud of his pedigree which reached back to the Levush. The pedigree to the Levush was something that Rav Kook had in common with his father-in-law ADeReT. In the letter written by Rav Kook’s paternal great-uncle, Rabbi Mordechai Gimpel Yaffe of Rozhinoy, to the Trisker Maggid, Rabbi Abraham Twersky, Rabbi Yaffe mentions their remote common ancestor, the Levush.

[3] The title is taken from the verse in Ezekiel 24:17: “Pe’erkha havosh ‘alekha” (“Bind your head-tire upon you”). The Rabbis interpreted the head-tire as a reference to the head-tefillah; see b. Mo‘ed Katan 15a.

[4] y. ‘Eruvin 10:1; b. Menahot 37a; Maimonides, MT, Hil. Tefillin 4:1; Rabbi Joseph Karo, Shulhan ‘Arukh, Orah Hayyim 27:9.

[5] m. Megillah 4:8.

[6] Deuteronomy 6:8.

[7] Shulhan ‘Arukh, Orah Hayyim 27:1.

[8] In Hevesh Pe’er, chap. 2, the author points out that there already appeared in print a small booklet with diagrams, “Tikkun ‘Olam ‘im tsiyurim,” but writes that the error persists depite that.

[9] Rav Kook’s first wife, Alta Batsheva, daughter of ADeReT, died at a young age, leaving him to raise their infant daughter, Freida Hannah. ADeReT suggested to Rav Kook that he marry Reiza Rivkah, ADeReT’s niece, daughter of his deceased twin brother, Tsevi Yehudah, Rabbi of Ragola. ADeReT had raised Reiza Rivkah in his home after her father’s death.

[10] Rabbi Jacob of Coucy, Sefer Mitsvot Gadol, positive commandment 3; Hevesh Pe’er, chap. 2. At the end of positive commandment 3, Rabbi Jacob gives the exact year of his campaign in Spain: 4996 anno mundi or 1236 C.E.

Urbach writes that this role of the itinerant preacher, or darshan, is without precedent among the French Tosafists; he conjectures that in this respect, Rabbi Moses of Coucy came under the influence of Hasidei Ashkenaz. See E.E. Urbach, Ba‘alei ha-Tosafot (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1995), pp. 466-470. Concerning specifically French Jewry’s laxity when it came to observing the commandment of tefillin, see ibid. p. 469, n. 13 (citing Tosafot, Shabbat 49a, s.v. ke-Elisha Ba‘al Kenafayim, and Rosh Hashanah 17a, s.v. karkafta de-lo manah tefillin). The SeMaG refutes Rabbenu Tam’s understanding of “karkafta de-lo manah tefillin.”

[11] Rabbi Ya‘akov Moshe Harlap, quoted in Rabbi Moshe Tsevi Neriyah, Sihot ha-Rayah (Tel-Aviv, 1979), p. 191, and idem, Tal ha-Re’iyah (Tel-Aviv, 1993), p. 116. According to Rabbi Harlap, the Slonimer Rebbe reached out to ADeReT, hoping that he could prevail upon his former son-in-law (and present nephew by marriage) to accept this magnaminous offer.

[12] Rav Kook’s erstwhile mentor in the Volozhin Yeshivah, Rabbi Naphtali Tsevi Yehudah Berlin (NeTsIV), was so enamored of Hevesh Pe’er that he kept it in his tallit bag. See the Introduction of Rabbis Yitshak Arieli and Rabbi Uri Segal Hamburger to the Jerusalem 1925 edition of Hevesh Pe’er, p. 2.

[13] See Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan, Mishnah Berurah (Warsaw, 1884) to OH 27:9. In the Be’ur Halakhah, Rabbi Kagan sought support for this prescription in the manuscript glosses of “the Gaon Rabbi El‘azar Harlap” to Ma‘aseh Rav (a collection of the practices of the Vilna Gaon). If I am not mistaken, these notes would have been penned by the Gaon (and Mekubal) Rabbi Ephraim Eliezer Tsevi Harlap of Mezritch.

[14] Rabbi Ze’ev Wolf Turbowitz was born Rosh Hodesh Iyar, 1840 in Baboina near Kletsk and was known in his youth as the “Ilui of Baboina.” His first wife was from Izilian. After his marriage, he devoted himself exclusively to study of Torah, whereby he was then known as the “Porush of Izilian.” At a tender age he began to study Kabbalah. (Among his writings was found a work on Zohar.) In 1863, he was appointed as a rosh metivta in Minsk. In 1866, he received his first rabbinical position in Swislowitz. In 1875, he assumed the rabbinate of Kletsk. Afterward, he served a stint in Wolpa. And finally in 1889, he was elected rabbi of Kraz, where he served until his death on the 14th of Kislev, 5682 [i.e. 1921]. These biographical details were gleaned from his son-in-law Rabbi Yosef Kesler’s introduction to the Brooklyn 1939 edition of Tif’eret Ziv, p. 4.

Rabbi Eitam Henkin hy”d wrote of the interface between Rabbi Turbowitz and Rabbi Eliyahu Goldberg, mentor of Rabbi Yehiel Mikhel Epstein (author of ‘Arukh ha-Shulhan). Besides corresponding with Rabbi Goldberg in halakhic matters, Rabbi Turbowitz delivered a moving hesped (eulogy) for Rabbi Goldberg in 1875 in the town of Kletsk, Rabbi Goldberg’s birthplace. See Rabbi Eitam Henkin, Ta‘arokh Lefanai Shulhan (Israel: Maggid, 2018), pp. 359-360, 363.

[15] See Rabbi Ze’ev Wolf Turbowitz, Tif‘eret Ziv (Warsaw, 1896), no. 1. Ziv is an acronym for Ze’ev Yekhuneh Volf.

The responsum is datelined “Wednesday, 16 Tamuz, 5651 [1891],” which means that it was penned the same year that Hevesh Pe’er was published. Rabbi Turbowitz does not mention the book by name, referring to it as “a new book that has appeared” (“sefer ehad hadash she-yatsa la-’or”).

By the same token, in responsum 12 of Tif’eret Ziv, where Rabbi Turbowitz engages with another early work of Rav Kook (in fact, his first), ‘Ittur Soferim, he refers to that work obliquely as “sefer ehad katan” (“a small book”). Rabbi Abraham Joshua of Pokroi had raised the question whether one who becomes bar mitsvah at night must recite once again the blessing for studying Torah (birkat ha-Torah), though he already recited it that morning. The editor, Rav Kook, devoted a few pages to resolving this problem. See ‘Ittur Soferim, Part Two (Vilna, 1888), 9a-10b. Rabbi Turbowitz made short shrift of the question. At the same time, he tackled the Vilna dayan, Rabbi Shelomo Hakohen, who had also raised the question in his work, Binyan Shelomo. In the Brooklyn 1939 edition of Tif’eret Ziv, the first two responsa are to Rabbi Shelomo Hakohen, who had defended his position to Rabbi Turbowitz.

According to Rabbi Turbowitz’s son-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Avigdor Kesler, the famous “Gadol of Minsk” (i.e. Rabbi Yeruham Yehudah Perlman) read Rabbi Turbowitz’s responsum concerning the placement of the head-phylactery before it went to print and approved its contents. See the supplement to the Brooklyn 1939 edition of Tif’eret Ziv, Kuntres Aharon, “Mele’im Ziv,” 2d-3a, footnote.

[16] Tif’eret Ziv, 6a. The quote is from b. Pesahim 66b: “Leave Israel alone! If they are not prophets, they are the children of prophets.” Rabbi Turbowitz’s remark is quoted in Yehudah Mirsky, Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), p. 23.

[17] Tif’eret Ziv 1:3 (6c).

[18] Tif’eret Ziv 1:16-21 (8c-9b). See Rabbi David Halevi (TaZ), Magen David to OH 8:15; cited in Mishnah Berurah to OH 25:12.

[19] See previous note.

[20] It may strike the reader as ironic that Rav Kook introduced at this point in the discussion the concept of rubo ke-khulo when he had earlier rejected its application. But from Rav Kook’s standpoint (and that of his father-in-law Aderet, see below note 35), that principle simply could not be applied to the area of the phylactery with its precise dimensions. “Shi‘urim halakhah le-Moshe mi-Sinai,” “Measurements are a law to Moses from Sinai” (y. Pe’ah 1:1, Hagigah 1:2; b. ‘Eruvin 4a, Yoma 80a, Sukkah 5b).

[21] Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook, “Kelil Tif’eret” in Hevesh Pe’er, ed. Rabbis Y. Arieli and Uri Segal-Hamburger (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1985), p. 46. Of course, the element of hesah ha-da‘at, i.e. whether one has “removed one’s awareness,” plays a crucial part in determining whether one must recite the blessing on the tefillin once again. See ibid.

Rav Kook’s hiluk (differentiation) between “‘etsem ha-mitsvah” and “ma‘aseh ha-mitsvah” (especially the terminology) is somewhat remarkable, issuing as it did from the pen of Rav Kook, who studiously avoided the school of Hasbarah with its abstract constructs and neologisms, then in vogue in the Lithuanian yeshivah world. The most famous proponent of Hasbarah was Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik (who would one day inherit his father Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik’s rabbinate in Brisk, whereupon he would be known as “Reb Hayyim Brisker”). The latter’s methodology of Talmudic analysis came to be known as the “Brisker derekh [ha-limud],” “the Brisker way.”

Rav Kook’s biographers have duly noted that his first mentor back in Dvinsk (since Rav Kook’s bar mitsvah), Rabbi Reuven Halevi Levin (known as “Reb Ruvaleh Denaburger”) had, so to speak, “immunized” Rav Kook against the trend of “sevarot” or newfangled “concepts.” Rabbi Reuven Levin was highly suspicious of sevarot that had not been enuciated already by the rishonim, the medieval authorities. (See Rabbi Kesler’s introduction to Tiferet Ziv, Brooklyn 1939, p. 8, par. 9, quoting Rabbi Reuven Levin, and ibid. sec. Hoshen Mishpat, responsum 46:6 [116c]: “It is not my way to say sevarot of my own cognizance.”)

And thus, when later Avraham Yitshak Kook arrived at Volozhin, “the mother of yeshivot,” he gravitated to the elder Rosh Yeshivah, Rabbi Naphtali Tsevi Yehudah Berlin (NeTsIV), known as a pashtan, a champion of the simple understanding of the text, rather than to his grandson-in-law, Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik, who was surrounded by budding scholars attracted to the exciting new method of Talmudic analysis that he was developing.

Although Rav Kook was never so outspoken as Ridbaz Wilovsky (“Reb Yankel Dovid Slutsker”) who satirized the new method as “chemistry,” Rav Kook was clearly on the other side of the great divide between Lithuanian Talmudists. This aversion of Rav Kook to the method of “hasbarah” was given eloquent testimony in recently unearthed correspondence concerning the unsuccessful attempt of Rabbi Shim‘on Shkop (a rosh yeshivah in Telz and later head of his own yeshivah in Grodna) to be accepted as Rosh Yeshivah of Merkaz Harav in Jerusalem. Speaking in Rav Kook’s name, his devoted disciple Rabbi Ya‘akov Moshe Harlap conveyed to Rabbi Hizkiyahu Yosef Mishkovski of Krinik (who had interceded on Rabbi Shim‘on Shkop’s behalf) the following laconic response:

Regarding the proposal concerning the Gaon Rabbi Shim‘on Shkop, may he live, to accept him as Rosh Yeshivah of Merkaz Harav, there is certainly nothing to discuss, for since the founding of the Yeshivah, this position is reserved for Maran [our master, i.e. Rav Kook], may he live, who plans to fill it himself. For Maran, may he live, wishes—and this is a strong desire—that the main method of learning of the Yeshivah be according to the order and method of the Gra [i.e. the Gaon Rabbi Elijah of Vilna], of blessed memory. Though he [i.e. Rav Kook] knows and feels also the great necessity of developing the methods of “hasbarot” (conceptualizations) and “havanot hegyoniyot” (logical understandings), he wants the main spirit of the Yeshivah to be based on his method, etc. Today I showed Maran, may he live, his honor’s letter, and what I wrote here is his response.

Rabbi Harlap’s letter is datelined “Monday, 2nd day of Rosh Hodesh Adar, 5686 [i.e. 1926], Jerusalem.” It was published in a Festschrift for his grandson, Rabbi Zevulun Charlop, Zeved Tov, ed. Ari S. Zahtz (New York: Yeshiva University Press, 2008), p. 103.

Inter alia, “Z. Wein” mentioned in the letter from Rabbi Shkop to Rabbi Tobolsky, expressing his desire to settle in the Holy Land (ibid. p. 101), is none other than [Rabbi] Ze’ev Wein a”h, father of Rabbi Berel Wein shelit”a. Rabbi Ze’ev Wein (1906-2004), a disciple of Rabbi Shkop, went on to study in Rav Kook’s Merkaz Harav in Jerusalem. He served for many years as a distinguished rabbi in Chicago.

Rabbi Shim‘on Shkop was famous for his method of “higayon” (logic), displayed in his magnum opus, Sha‘arei Yosher. (Rabbi Hershel Shachter shelit”a revealed to this writer [BN] that his father-in-law, Rabbi Yeshayah Shapiro, a rosh yeshivah at Torah Vodaath in Brooklyn, was instrumental in writing that work.)

This is not the place to discuss in any depth the differences between Rabbi Shim’on Shkop’s method and that of Rabbi Hayyim Brisker and his heirs. Two anecdotes should suffice. The Briskers quipped that Rabbi Shim‘on “had looked at the world and created the Torah” (“Istakel be-‘alma u-vara ’oraita”), a reversal of the Zohar’s adage, “[God] looked at the Torah and created the world” (“istakel be-’oraita u-vara ‘alma”). On one occasion, Rabbi Yitshak Ze’ev Soloveitchik (“Reb Velvel,” known as the “Brisker Rov,” for he inherited from his father Rabbi Hayyim the rabbinate of Brisk) met Rabbi Shim‘on Shkop and told him: “I removed from your student Rabbi Leib Malin the last sinew (gid) left from your teaching.” (The imagery is that of deveining or nikkur. Reb Velvel used the Yiddish verb, “treiberen.”) Both anecdotes were heard from Rabbi Shelomo Fisher shelit”a of Jerusalem.

[22] In 1895, Rav Kook left the town of Zeimel for the large city of Bausk, Latvia.

[23] Rabbi Ze’ev Wolf Turbowitz, Ziv Mishneh (Warsaw, 1904). The author has the rather unique distinction of viewing Maimonides as a kabbalist and finding kabalistic “sources” for his rulings. (Similarly, the introduction to the Warsaw 1896 edition of Tif’eret Ziv demonstrates the author’s proficiency in Lurianic kabbalah.) Though not unique in this respect, Rabbi Turbowitz is perhaps the most outspoken proponent of this peculiar methodology of studying Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah. Another Maimonidean commentator who occasionally resorts to this method of sourcing is Rabbi Joseph Rosen (the Rogatchover Gaon). See his Tsafnat Pa‘neah, Hil. ‘Avodah Zarah 12:6. Nowadays, Rabbi Hayyim Kanievsky’s Kiryat Melekh is replete with references to Zohar.

[24] b. Horayot 3b; and Rashi, Zevahim 26a, s.v. hikhnis rosho ve-rubo. Both are referenced by Rabbi Turbowitz.

[25] Rabbi Yitshak Arieli was one of the founders of Yeshivat Merkaz Harav and acted in the official capacity of “Mashgiah” of the Yeshivah. He is most famous for his work on the Talmud, ‘Eynayim le-Mishpat. Recently, Aharon Ilan, a great-grandson of Rabbi Yitshak Arieli, brought out his biography, ‘Eynei Yitshak (Jerusalem, 2018).

[26] Rabbi Uri Segal Hamburger was a descendant of Rabbi Moshe Yehudah Segal Hamburger of Novemeste (a disciple of the Hatam Sofer) who came to Erets Yisrael in 1857. Rabbi Uri Segal Hamburger resided in the Old City of Jerusalem until its conquest by the Jordanians in 1948. He penned a memoir of that tragic event, “Be-Tseiti mi-Yerushalayim.” One may find a short biography and a photograph of Rabbi Hamburger in ‘Eynei Yitshak, pp. 136-137.

[27] Rav Kook’s biographer and disciple, Rabbi Moshe Tsevi Neriyah, records that Rav Kook wrote in his haskamah (letter of approbation) to the publishers the following disclaimer: “In our holy land, which thank God, is full of Torah and fear of heaven, the admonition (azharah) is not so necessary. Nevertheless, I have not prevented re-issuing the book, for the benefit of our brothers in the diaspora, in areas where the matter is yet in need of correction” (Sihot ha-Rayah, pp. 189-190). This disclaimer does not appear in the printed version of the haskamah. Where did Rabbi Neriyah obtain it? The mystery was cleared up in the new edition of Sihot ha-Rayah (2015) published after Rabbi Neriyah’s passing. Rabbi Arieli’s son, Prof. Nahum Arieli, wrote to Rabbi Neriyah that he has in his possession much material that went into the making of the Jerusalem edition of Hevesh Pe’er edited by his father, including a “petek” (note) with those exact words. Rabbi Neriyah’s daughter, Tsilah Bar-Eli, granted Aharon Ilan permission to include a facsimile of Nahum Arieli’s letter to her father (on stationery of Bar-Ilan University) in the biography of Rabbi Arieli, ‘Eynei Yitshak, p. 139.

[28] Rabbi Arieli’s promised “Kuntres Aharon” was never published. Remnants of the manuscript are in the possession of his heirs. Rabbi Neriyah speculated that financial considerations prevented its publication in Hevesh Pe’er. See ‘Eynei Yitshak, p. 138, n. 102.

[29] On the inside of the book, Rabbi J. Kesler’s address is given as: “146 Beach 74th Street, A[r]verne, Long Island.”

[30] It is important to note that the two collections do not overlap. The responsa on Orah Hayyim that appeared in the Warsaw 1896 edition of Tif’eret Ziv, were not included in the Brooklyn 1939 edition. In their stead, appear more recent responsa on Orah Hayyim. In terms of sheer quantity, the second collection by far outstrips the first. The first Warsaw edition has 122 pages; the second Brooklyn edition, 488 pages.

[31] “Mele’im Ziv,” 2a-b.

[32] “Mele’im Ziv,” 2b-2c.

[33] “Mele’im Ziv,” 2d.

[34] “Mele’im Ziv,” 3a.

[35] “Mele’im Ziv,” 3a-b.

[36] The facsimile occurs in Rabbi Kesler’s introduction to the book on p. 7. It is transcribed in “Mele’im Ziv,” 3b.

If not for the evidence of the facsimile, it would indeed be difficult to accept that Rav Kook once entertained even the remote possibility of invoking the principle of rubo ke-khulo in this regard.

[37] To this day, Lubavitcher Hasidim wear very large tefillin.

[38] “Mele’im Ziv,” 3b-c.

[39] “Mele’im Ziv,” 3d.

In 1893, ADeReT left the community of Ponevezh to assume the rabbinate of Mir.