A Short Note Regarding an Illustrated Title Page and A Possible Unicum

A Short Note Regarding an Illustrated Title Page and A Possible Unicum

There are a series of books, Seder ha-haʻarakhah ve-haHanhagah, that record the tax law and taxes paid by the Mantuan community and were published in Mantua. [1] The taxes were calculated by communally elected assessment formulators. The taxes were used to support the entire communal infrastructure, including the administration of communal organizations and funds for the poor. As today, each person would provide an accounting of their funds reducing their taxable income based upon recognized deductions and certain exempted property. The formulators were wholly responsible for the determination of the specific levied taxes and could reject suspect ax filings and impose fines.

The first edition was published in 1651 and each edition covers three years, of which the National Library has 17 editions. The British Library holds 12, seven that are not in the National Library’s collection. Vinograd lists 22 editions, six in neither library. [2] (A full bibliography appears below)

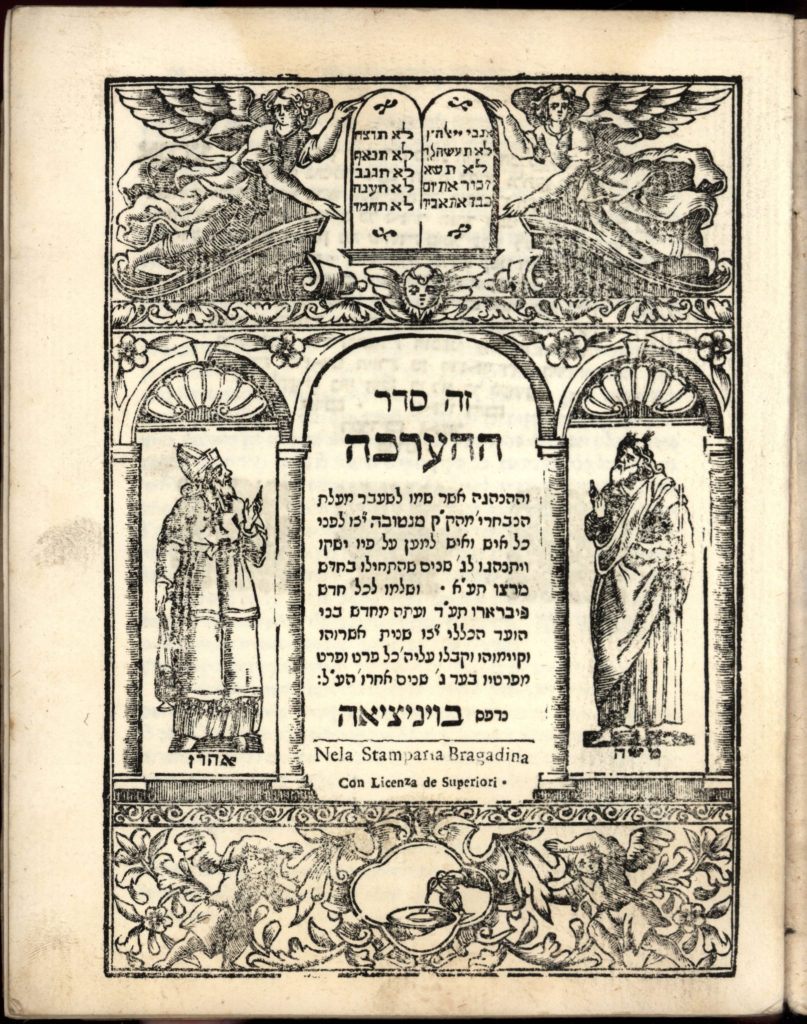

There is, however, at least one edition in the series that was not published in Mantua, the most logical location, but in Venice by Bragadin in 1711. The likely reason for the change in venue is that from 1707-1712, there were no books printed in Mantua. [3] Nonetheless, these records were so important that the community went to Venice to publish the records.

Steinschneider, based upon Wolf’s bibliography, does identify this edition of the work. [4] But the book is not extant in the Bodleian Library.[5] Nonetheless, no modern bibliography, e.g. Vinograd or Friedberg, records the Venice edition nor does the National Library or any other library I can identify (based on a search of WorldCat) own a copy of the book. There is one copy, however, in the Gross Family Collection in Tel Aviv, and is possibly a unicum – the only extant copy. Although as Judge Meyer Sulzberger, himself an avid book collector, noted that caution is necessary when identifying a unica, because “that the great weakness about a unicum is that presently one or two other people are found to have the book, and instead of contently agreeing that each of them has a unicum, each feels the value of his possession has been materially impaired.” To this we can add that without concrete evidence of the book’s singularity, there may be private collections or public ones whose holdings are insufficiently cataloged to make a confident identification regarding the rarity of any book. Indeed, Sulzberger provides many examples of books thought to unica, only to be identified as “merely” rare.[6]

I should also note that the Venice copy has a nice title page with Moses and Aaron. (For a discussion of depictions of Moses and Aaron on Hebrew title pages see our earlier post here.) A very similar title page appears on a later book printed in Mantua, 1720, Mishlei ve-Eiov, although in this instance it is David and Solomon who flank the title.

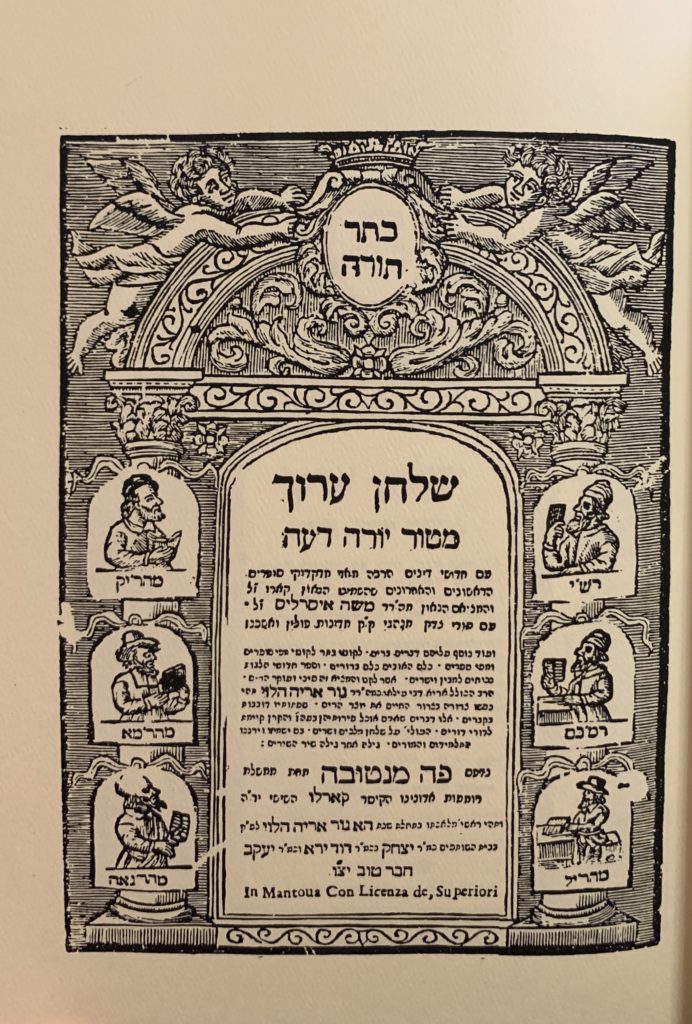

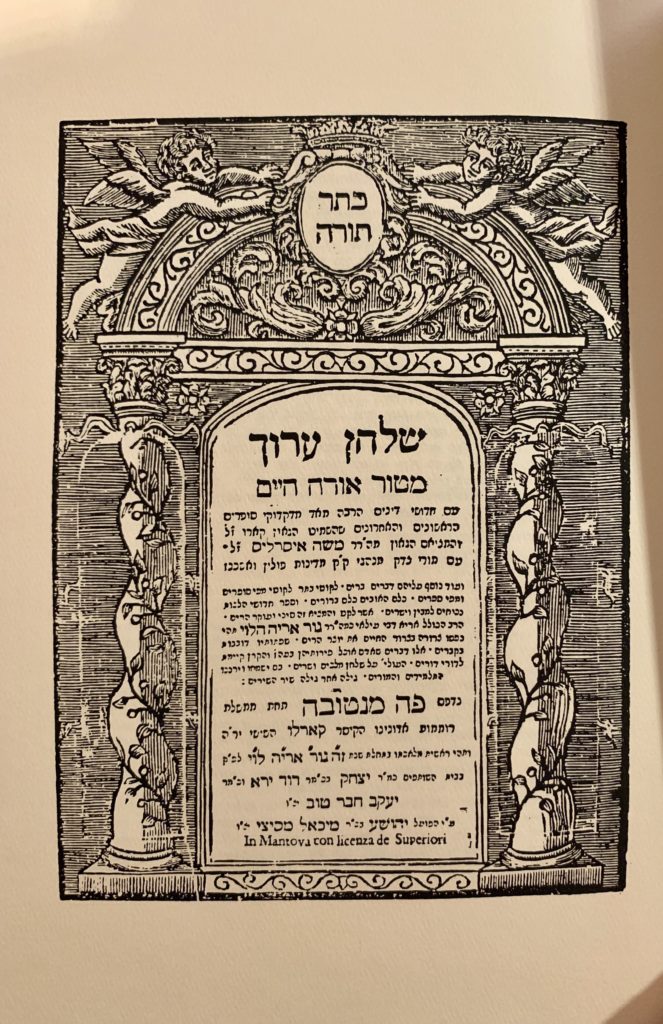

Additionally, the depiction of the Moses, Aaron, Solomon and David are similar to the ones that appear – Rambam, Rashi, R Yosef Karo, Rama, and the author – on the Gur Areyeh, a commentary on Shulkhan Orakh, Mantua, 1722.

There are two editions of this book printed within a year of one another. The second printing lacks the images entirely and the first they only appear in Orakh Hayyim, and, although not noted in bibliographies or articles regarding the book, in at least one example the title pictorial title pages also appears in Yoreh Deah.

The remaining three (or two) volumes do not contain the images. This led some to speculate that the images were deliberately removed, and that page was ripped out at the behest of the Mantua rabbinate and a variety of theories are offered, ranging from concern over reproducing human image to the inclusion of the author among such a distinguished group was egotistical, that the Rambam lack ed peyot, or that the portraits are just not flattering. [7]

But, both the claim of censorship and the rationale are unsupported. Most extant copies include that page and there are many earlier examples of books containing human images including of biblical figures, many without peyot, or not dressed in flattering clothing. There is no independent evidence to suggest anything other than a benign reason, perhaps the woodcuts wore out. This aligns with the fact that the printer was known for crude lettering so much so that it nearly lost its ability to print at all and only survived because another party stepped in. Thus it is unlikely the lack of the portraits in the later volumes is an instance of censorship.[8]

* The identification of the Gross edition as a unicum is only preliminary and still a work in progress. The author encourages anyone with additional information regarding this edition to comment or send an email to seforimblog@gmail.com

[1] See Shlomo Simonshon, Tolodot ha-Yehudim be-Duhosot Mantua, vol. 1 (Jerusalem, 1963), 274-86; see also Marvin J. Heller, The Seventeenth Century Hebrew Book: An Abridged Thesaurus, vol. 2 (Leiden: Brill, 2011), 957.

[2] For the NLI listing see here; Diana Rowland Smith, Second Supplementary Catalog of Hebrew Books in the British Library 1893-1960, vol. 2 (London: British Library, 1994), 599; Joseph Zedner, Catloglouge of the Hebrew Books in the Library of the British Museum (London, 1867), 510 recording Mantua 1759; Yeshayahu Vinograd, Otsar ha-Sefer ha-Ivri (Jerusalem: Machon Lebibliograhia Memuhshevet, 1994).

[3] See Ch. B. Freidberg, Tolodot ha-Defus ha-Ivri be-Italia: Be-Midenot Italiah, Aspnyah-Portugal, ve-Turgemah she-Melfenim (Tel Aviv: Bar-Yeda, 1956), 20. Friedberg does not explain the cause of the stoppage.

[4] Moritz Steinschneider, Catalogus Librorum Hebraeorum in Bibliotheca Bodleiana (Berollini: Ad. Friedlander, 1852-1860) columns 625-66; Johann Christoph Wolf, Bibliothecae Hebraeae, vol. 3 (Hamburg: Christoph Felgineri Viduam, 1827), 1207-08 (Steinschneider’s citation to Wolf should be corrected to read vol. 3 and not vol. 2).

[5] See A.E. Cowley, A Concise Catalogue of the Hebrew Printed Books in the Bodleian Library (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1929), 410 (listing only Mantua).

[6] Meyer Sulzberger, “Books and Bookmen,” Menorah XXXVI (Jan. 1904), 38-40. For other Hebrew unica see Marvin J. Heller, “Unicum, Fragments, and Other Hebrew Book Rarities,” Judaica Librarianship 18 (2014), 130-53.

[7] See Shmuel Weiner, Daat Kedoshim: Pesak Herem: Mazkeret Rabanei Italiah (Petroberg: Berman Press, 1897), 38**; Aviad Cohen, “Diuknot Hakhamim: Bein Halkha le-Maashe,” Mahnayim 10 (1995). See Mifal ha-Bibliographia ha-Ivrei entry Gur Areyeh .

One scholar viewed the selection of personages to grace the title page as an indication of their imporatance. Specifically the inclusion of the Mahril was used to demonstrate his unique contribution to the formation of the Shulchan Orakh. See Yisrael Peles, Mevo ve-Hosafot le-Sefer Mahril (Jerusalem: Machon Yerushalim, 2016), 258. (Thanks to Eliezer Brodt for providing this source).

[8] Friedberg, Tolodot ha-Defus ha-Ivri, 20-21. For another example of spurious reasons for a change to the title page, see Dan Rabinowitz, “Sheti ha-Girsot shel Shu”t ha-Bakh, Mahadurot Frankfort TN”Z: Totsot shel Shikul Tsniut, Sha’arim be Shut ha-Bach,” Alei Sefer 21(2010), 99-112.

Bibliography of Seder ha-Ha’arakhah

Mantua, 1651(BL)

Mantua, 1656 (NLI)

Mantua, 1670 (V)

Mantua, 1675 (BL)

Mantua, 1679 (NLI)

Mantua, 1682 (V)

Mantua, 1685 (V)

Venice, 1711 (Gross)

Venice, 1714 (Wolf)

Venice, 1717 (Wolf)

Mantua, 1722 (BL)

Mantua, 1722 (BL) (& a variant)

Mantua, 1726 (NLI)

Mantua, 1729 (V)

Mantua, 1732 (NLI)

Mantua, 1735 (NLI)

Mantua 1737 (BL)

Mantua, 1739 (NLI)

Mantua, 1743 (BL)

Mantua, 1747 (NLI)

Mantua, 1750 (NLI)

Mantua, 1753 (NLI)

Mantua, 1756 (NLI)

Mantua, 1759 (NLI)

Mantua, 1773 (BL)

Mantua, 1777 (NLI)

Mantua, 1780 (NLI)

Mantua, 1783 (V)

Mantua, 1786 (NLI)

Mantua, 1789 (NLI)

Mantua, 1793 (V)

Mantua, 1795 (NLI)

Mantua, 1798 (NLI)