Kabbala, Halakha and Kugel: The Case of the Two Handed Blessing

Kabbala, Halakha and Kugel: The Case of the Two Handed Blessing*

In parshat Vayehi, Yaakov simultaneously blesses his two grandchildren, Ephraim and Menashe by placing one hand upon each of their heads. Today, there is a widespread custom of blessing one own’s children on Friday night (although some only do it on the eve of Yom Kippur). This custom most likely originated with the Hasedi Ashkenaz in the 14th century but quickly spread to the rest of Europe, including France, Spain, and Italy.[1] The exact details of the blessing, however, are subject to some variation.

The earliest sources mention only the priestly blessing and not Yaakov’s.[2] It was not until the 18th century, R. Yaakov Emden propose the specific usage of Yaakov’s blessing to his grandsons “God shall make you like Ephraim and Menashe.” Likewise, even within those sources they are inconsistent as to whether both hands are to be used or only one. Some provide that one hand should be used because it has 15 joints the same number of words as in the priestly blessing, while others urge two hands because they contain 60 bones which corresponds to the word “סמך” “somekh” “to lay hands” to be read as the letter “סמ״ך” “samach” and correspond to the numerical value of sixty rather than the literal translation equaling the number of letters in Birkat Kohanim. These sources disagree because of the symbolic nature of the hands vis-à-vis the blessing.

The anonymous book, Hemdat Yamim, states that one should only use the right hand to bless. Likewise, R. Yitzhak Lampronti records that some refrain from using two hands to avoid “mixing hesed with din” corresponding to the right and left hands respectively. But he rejects that and he used both hands.

R. Emden firmly rejects the idea of singlehanded blessings. He explains that Moshe and others used two. Yaakov was but an exception as he wanted to bless both of his grandsons simultaneously because he was already changing the order and wanted to minimize, as much as possible, the differences between the two. Further blessing the younger before the older would be an unforgivable insult. Thus, this was a special case where he was compelled to use one hand.[3] But in the late 19th century, a one handed blessing was suggested because of halakhic reasons.

In 1779, R. Yehezkel Landau was born in Vilna. In 1793 he married his cousin, the daughter of Tzvi Hirsch and Mushka Zalkind, Haye Sorah.[4] Unexpectedly, an event surrounding Landau’s wedding would become a touchstone for birkat ha-banim.

R. Landau was among those who were privileged to study with the Gaon and received his particular form of learning that eschewed pilpul and focused on peshat.[5] Additionally, R. Landau considered himself a talmid muvhak of and prayed in the same synagogue as R. Hayyim Volozhin.[6] That synagogue, the Parnes Kloyz, also claimed a number of other important members including R. Avraham Abele Poswoler, R. Landau’s brother-in-law.[7] With the death of R. Abele in 1806 R. Landau took over the position as Rosh Av bet Din of Vilna.[8] The position was first offered to R. Akiva Eiger but he turned it down.[9] R. Landau held that position until his death in 1870.

Until this point the discussion regarding whether to use two hands or one is limited to symbolic or kabalistic reasons. But there are those who argue that there is a legal issue with using two hands and they attribute this view to the Gaon. Determining the Gaon’s practices is a very difficult task, he did not write a book of customs and instead most of what we have is from second hand or third hand sources, many of which are contradictory or unsupportable.[10]

Close to one hundred years after the Gaon died, the siddur, Siddur ha-Gaon be-Nigleh u-Nistar, was published by Naftali Hertz, and for the first time it is recorded that the Gaon only used one hand for a blessing. The source for this practice is unclear. The “Nigleh” portion is generally taken from Ma’ashe Rav and Likutei Dinim meha-Gra, neither of which records this practice.

R. Barukh ha-Levi Epstein, however, records a story about that Gaon that is related to the prohibition of a non-kohen reciting the priestly blessings in the synagogue. In Epstein’s commentary on the Torah, Torah Temimah, he posits a novel ruling that not only is a non-kohen prohibited from blessing the congregation but is prohibited from ever using two hands – like the priests – to bless anyone. According to Epstein, such a practice would violate a biblical commandment. But he wanted to address as to why he is the first to raise this issue and rather than concede that he is the source of this innovative ruling he records a story from “a trustworthy source” that “when the Gaon of Vilna blessed R. Yehezkel Landau the Moreh Tzedek of Vilna at his huppa, the Gaon only placed one hand on R. Landau’s head during the blessing. Those present asked the Gaon to explain his practice and he replied that only the priests in the temple can use two hands.”[11] Thus, R. Epstein is able to “toleh atsmo be-ilan gadol” (one should hang themselves on a big tree).

Indeed, R. Epstein’s version of the Gaon’s position is still accepted today. Two siddurim that were recently published based upon the Gaon’s practices both record that it was his opinion that one must only use one hand because “only the priests in the temple were permitted to use two hands.” Both cite R. Epstein as their source.[12]

That R. Landua received the Gaon’s blessing is attested to on his epithet.

“חן הוצק בשפתיך כי גברה עליך ברכת אליהו גאון ישראל.”

“Grace was placed upon his lips because he was overtaken by the blessing of Eliyahu Gaon of Israel.”[13] Nonetheless, the exact details of that blessing are not as clear. Indeed, the details of R. Epstein’s version that was transmitted by a “trustworthy source” seem somewhat suspect. First, R. Landau would not have been referred to as a מו״ץ because he oversaw the entire bet din system in Vilna and controlled all of the moreh tzedeks. Hence R. Landau was referred to as Rosh Av Bet Din “Ravad” or ראב״ד.[14] Second, the Gaon was not known for getting out much. He no longer studied at all in what was known as the Gaon’s kloyz that was located in the Great Synagogue Courtyard (shulhoyf) but studied in the same house he lived in, a location known as the Slutzki building.[15] While R. Landau was well-regarded none of the other histories of Vilna that discuss R. Landau and mention the he studied with the Gaon or the Gaon’s blessing also include the Gaon’s attendance at the wedding.[16] Finally, the Gaon’s commentary to Shulchan Orakh does not mention any issue with a non-kohen using two hands, nor does it appear in any of the books collecting the Gaon’s customs.[17]

While admittedly none of the above issues are dispostive, there is a far better reason to discount R. Epstein’s version because there is a more reliable alternative version of the story that R. Epstein records, and according to this version, there is nothing to suggest that the Gaon deliberately avoided using two hands nor that there is any reason to do so. Indeed, stories that are attributed to the Gaon are notoriously unreliable. Already with the first “biography” of the Gaon, R. Dovid Luria cautioned that “the greatness of my teacher, Rabbenu ha-Gadol z’l [ha-Gaon] is such that there are many stories and legends attesting to that greatness there are as many variations, embellishments and deficiencies in every story.” In this instance, however, we have the benefit of hearing the story directly from the protagonist, R. Landau.

R. Ben-Tzion Alfes

Ben-Tzion Alfes was born in Vilna in 1851 and when he was a young boy spent time in the Gaon’s Kloyz and met R. Landau. Alfes records in his autobiography that “R. Landau recalled that the Shabbat after he was married, his father-in-law brought him to the Gaon to receive a blessing. When he arrived the Gaon was in the middle of his lunch meal, eating kugel.[18] R. Landau was wearing the new fur hat he received for his wedding and when the Gaon went to place his hands on R. Landau’s head, he turned away so that the Gaon wouldn’t dirty the fur hat with his greasy hands. The Gaon ended up just putting one hand on the hat and blessed R. Landau. R. Landau lived very long, over ninety and never required eyeglasses, and for the rest of his life he was disappointed regarding his small mindedness of valuing the hat more than the hands of the Gaon.”[19]

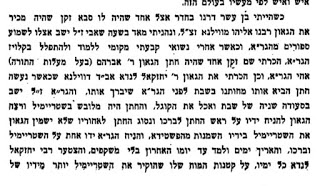

כשהייתי בן עשר דרנו בחדר אצל אחד שהיה לו סבא זקן שהיה מכיר את הגאון רבנו אליהו מווילנא זצ”ל, ונהניתי מאד בשעה שאבי ז”ל ישב אצלו לשמוע ספורים מהגר”א, וכאשר אחרי נשואי קבעתי מקומי ללמוד ולהתפלל בקלויז הגר”א, הכרתי שם זקן אחד שהיה חתן הגאון ר’ אברהם (בעל מעלות התורה) אחי הגר”א, וכן הכרתי את הגאון ר’ יחזקאל לנדא אב”ד דווילנא שכאשר נעשה חתן הביא אותו מחותנו בשבת לפני הגר”א שיברך אותו, והגר”א ז”ל ישב בסעודה שניה של שבת ואכל את הקוגל, והחתן היה מלובש בשטריימיל ורצה הגאון להניח ידיו על ראש החתן לברכו ונסוג החתן לאחוריו שלא ישמין הגאון את השטריימיל בידיו השמנות מהפשטידא, והניח הגר”א ידו אחת על השטריימיל וברכו, והאריך ימים ולמד עד יומו האחרון בלי משקפים, והצטער רבי יחזקאל לנדא כל ימיו, על קטנות המוח שלו שהוקיר את השטריימיל יותר מידיו של הגר”א

According to R. Landau it was his own fault that the Gaon only used one hand and it had nothing to do with symbolism, kabbala and certainly not because of a halakhic concern. It came down to kugel and fur hats.[20]

* A different version of this article previously appeared in Or HaMizrach in Hebrew. Dan Rabinowitz, “Birkat ha-Banim be-Sheti Yadim: Mesoret ha-Gra be-Nedon,” Or HaMizrach 51, 3-4 (2006), 181-85. Additionally, Professor Daniel Sperber modified and added additional materials to it for Bar Ilan’s Shabbat Torah pamphlet. Daniel Sperber, “Al Birkat ha-Banim,” Daf Shevoei (University Bar Ilan) Parshat Vehi, 2008, no. 735.

[1] See Yecheil Goldhaver, Be’er Sheva, in Bunim Yoel Tevesig, Minhagei ha-Kehilot (Jerusalem: Le’or, 2005), 186-89. See also, Shmuel Ashkenazi, Alpa Beta Kadmeta (Jerusalem, 2010), 207-09.

[2] R. Eliyahu Dovid Rabinowich Toemim, however, incorrectly asserts that the priestly blessing was not part of the blessing of the children. Instead, he suggests that since the inception of the custom on Yaakov’s blessing was used. Eliyahu Dovid Rabinowich Teomim, Shu”t Ma’aneh Eliyahu (Jerusalem: Yeshiva Har Etzion, 2003), no. 122, 349.

[3] Hemdat Yamim, (Venice, 1812), Helek Shabbat, chapter 7, 48; Yitzhak Lamporti, Pahad Yitzhak ha-Shalem (Jerusalem, 1998), ma’arekhet ha”Bet,” 52; Yaakov Emden, Siddur Ya’avetz (Jerusalem, 1992), 564-65. See Goldhaver who provides many of these sources and the additions of Eliezer Brodt in Yerushatanu 2 (2008), 205-206 (Eliezer also kindly provided additional sources for this post). For an example of a death bed blessing see Michel Hakohen Brever, Zikhronot Av u-Beno (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1966) 122

[4] The Zalkinds would later establish a kloyz, with a women’s section, that was alternatively referred to by Reb Herschel Zalkinds Kloyz and perhaps more notably by his wife’s name: Mushke Leybele Zalkinds kloyz. The kloyz is no longer extant but was located in Vilna’s Old Jewish quarter on what is today Šv. Mikalojaus Street. Synagogues in Lithuania, N-Z: A Catalogue, eds. Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Sergey Kravtsov, Vladimir Levin, et.al. (Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of Arts Press, 2012) 312.

[5] Shmuel Yosef Fuenn, Kenest Yisrael: Zikhronot le-Toldot Gedolei Yisrael ha-No’adim le-shem be-Torotum, be-Hokhatum, ube-Ma’asehem (Warsaw, 1886), 517.

[6] Hillel Noach Steinschneider, Ir Vilna (Vilna, 1900), 32.

[7] For a biography of R. Abele, see Ir Vilna, 19-29. His third wife, Fagie, was R. Landau’s sister. For more about the Kloyz see Cohen-Mushlin, Synagogues in Lithuania N-Z, 308 and for more details on the building and the Parnes see Aelita Ambrulevičiūtė, Houses that Talk: Sketches of Vokiečiu Street in the Nineteenth Century (Vilnius: Auko Žuvys, 2015), 91-95.

[8] Ir Vilna, 32.

[9] Ir Vilna, 30-31.

[10] See the comments of R. David Luria, “the greatness of my teacher, Rabbenu ha-Gadol z’l [ha-Gaon] is such that there are many stories and legends attesting to that there are as many variations, embellishments and deficiencies in every story.” R. David Luria, “Letter from ha-Gaon ha-Rav RD”L,” in Yeshua Heschel Levin, Aliyot Eliyahu (Vilna, 1857), 4.

[11] Barukh Halevi Epstein, Torah Temimah: Bamidbar 6:33.

[12] Siddur Aliyot Eliyahu (Machon Ma’dani Asher, 1999); Siddur Ezer Eliyahu (Jerusalem: Kerem Eliyahu, 1998).

[13] Ir Vilna, 35.

[14] See Ir Vilna, 102.

[15] For more on this building and the history of it and the Gaon’s kloyz see Shlomo Zalman Havlin, “ ‘Ha-Kloyz’ shel ha-Gaon me-Vilna Zts”l, Helek shel ‘Pinkas ha-Kloyz,’” in Yeshurun 6 (1999), 678-85; Dan Rabinowitz, The Lost Library: The Legacy of Vilna’s Strashun Library in the Aftermath of the Holocaust (Waltham: Brandeis University Press, 2018), 55-58.

[16] See, e.g. Ir Vilna, 32; Keneset Yisrael, 517-18.

[17] Even the siddur that does provide that the Gaon’s custom was to use just one hand there is no mention that the practice was because of potentially violating a biblical commandment.

[18] Kugel was among the customary foods eaten on Shabbat across Europe. Herman Pollack, Jewish Folkways in Germanic Lands (1648-1806): Studies in Aspects of Daily Life (Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1971), 112, 275n39.

Hasidic thought imbued kugel with special powers and it occupied a lofty place in its rituals. See Allan Nadler, “Holy Kugel: The Sanctification of Ashkenazic Ethnic Foods in Hasidism,” in Food and Judaism: A Special Issue of Studies in Jewish Civilization 15 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 193-214 (my thanks to Shaul Stampfer for calling this source to my attention). See also Joan Nathan, “Kugel Unraveled,” New York Times Sept. 28, 2005, F1.

Kugel was one of the foods that originated in Germany and spread to eastern Europe and both Jews and non-Jews ate it. See Pollack, Jewish Folkways, 112. Other traditional foods include fish, cholent, tsimes, farfl, kneydlekh, kikhelekh, lokshn and kasha. For fish see Moshe Hallamish, Ha-Kabbalah be-Tefilah be-Halakha, u-be-Minhag (Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 2000), 486-506; for the others see Pollack, Jewish Folkways, 100-112.

Hasidic thought imbued kugel with special powers and it occupied a lofty place in its rituals. See Allan Nadler, “Holy Kugel: The Sanctification of Ashkenazic Ethnic Foods in Hasidism,” in Food and Judaism: A Special Issue of Studies in Jewish Civilization 15 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 193-214 (my thanks to Shaul Stampfer for calling this source to my attention). See also Joan Nathan, “Kugel Unraveled,” New York Times Sept. 28, 2005, F1.

Kugel was one of the foods that originated in Germany and spread to eastern Europe and both Jews and non-Jews ate it. See Pollack, Jewish Folkways, 112. Other traditional foods include fish, cholent, tsimes, farfl, kneydlekh, kikhelekh, lokshn and kasha. For fish see Moshe Hallamish, Ha-Kabbalah be-Tefilah be-Halakha, u-be-Minhag (Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 2000), 486-506; for the others see Pollack, Jewish Folkways, 100-112.

[19] Ben Tzion Alfes, Ma’ashe Alfas: Tolodah u-Zikhronot (Jerusalem, 1941), 9-10.

[20] Today if one wants to combine the two, there is a recipe for striemel kugel here.