The Humble Artichoke

The New York Times recently discussed a novel ruling of the Israeli Chief Rabbinate. The Rabbanut held that artichokes fall into the category of prohibited foods. This is not because they are listed as such in the Torah. Rather the expansion of the biblical category is because of a secondary concern, the presence of insects. Those insects may reside in the heart which without opening the tight leaves that comprise the vegetable one is unable to determine if insects are present, thus, eating artichokes whole risks also ingesting insects.

Jews in Italy, however, took issue with this ruling. They pointed to a long-standing tradition of eating artichokes whole after deep frying. That tradition places the creation of the dish sometime in the 16th century in the Jewish ghetto in Rome. Indeed, their preparation is so intertwined with Jews, in Italian it is called Jewish-style artichoke—Carciofo alla giudia. Today many travel books include this delicacy among those to try in Italy listing various kosher restaurants that offer the Jewish Artichoke. The Rabbi of Rome refused to reform the practice of Italian Jews and continues to eat and provide his hechsher to restaurants which serve this vegetable prepared in the traditional manner.[1]

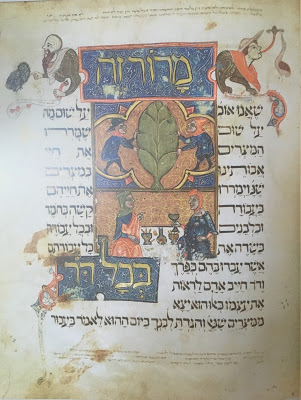

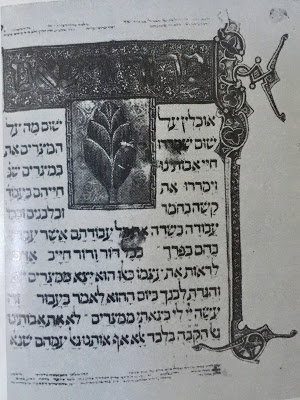

The history of how the fried artichoke became associated with Jews is somewhat murky but likely dates at least to the 16th century. But we have even earlier manuscript evidence that artichokes were eaten by Jews. Indeed they were eaten at a time when Jews were especially punctilious regarding food, Pesach. A number of medieval haggadot contain illustrations of marror, most include a leafy green of some type. Two haggadot, the Rylands and the Brother, composed in the mid/late-14th century depict marror as an artichoke. [2]

[1] Regarding the autonomy of the local rabbinate see Teshuvot haRosh, Klal 21, 8-4, 9-2, and generally the sources collected in HaMahkloket beHalakha, Hanina Ben-Menahem, Neil Hecht, Shai Wosner, eds., vol. 2 (Boston: Institute of Jewish Law Boston University School of Law, 1993), 753-820.

Students of history will recall that this is not the first time that the norms and traditions of the Italian Jews came into conflict with the different prevailing norms among other groups of Jews. In the controversy engendered by the publication of the pamphlet Divrei Shalom ve-Emet by Naftali Herz Wessely in the aftermath of Emperor Joseph II’s Edict of Toleration, which called for educational reform among his Central European subjects. After his pamphlet was found objectionable and insulting by leading rabbis, Wessely wrote to rabbis in Italy, believing that many of the ideas he was advocating, like a graded curriculum, a non-exclusive emphasis on Talmud, and use of the general vernacular, were well within the norms of their tradition. In fact, with the exception of only one of the Italian rabbis, R. Ishmael Ha-kohen of Modena, all the others agreed and supported him and helped the controversy die out. These aspects of the Wessely affair are discussed in Lois C. Dubin, “Trieste and Berlin: The Italian Role in the Cultural Politics of the Haskalah,” chapter 8 in Jacob Kats, ed., “Towards Modernity: the European Jewish Model” (New York, 1987) and the series of articles by Yisrael Natan Heschel in Kovetz Beit Aharon ve-Yisrael 8 (1993) titled “דעתם של גדולי הדור במלחמתם נגד המשכיל נפתלי הירץ וויזל.”

[2] The Rylands Haggadah manuscript is discussed in Katrin Kogman-Appel, Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain: Biblical Imagery and the Passover Holiday (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2006) 91-97. The Brother manuscript has recently been reprinted in full with an excellent introduction by Marc Michael Epstein in addition to other relevant articles. The Brother Haggadah: A Medieval Sephardi Masterpiece in Facsimile (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2016). For a discussion of the identification of marror see Zohar Amar, Merrorim: Hameshet Minei haMarror sheAdam Yotseh Bahem Yedei Hovato bePesach (Modiin [], 2008).