The Yiddish Press as a Historical Source for the Overlooked and Forgotten in the Jewish Community

The Yiddish Press as a Historical Source for the Overlooked and Forgotten in the Jewish Community

by Eddy Portnoy

Eddy Portnoy is Senior Researcher and Director of Exhibitions at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. He is the author of the recently-published (and much acclaimed, and fun) book, Bad Rabbi: And Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press (Stanford, 2017), available here (https://www.amazon.com/Bad-Rabbi-Strange-Stories-Stanford/dp/150360411X).

This is his first contribution to the Seforim Blog.

Sanhedrin 25 has this pretty well-known, somewhat rambling bit about what sorts of people are trustworthy enough to serve as witnesses in court. It’s pretty standard stuff. However, as part of this discussion, we get to learn about some early gambling practices among the Jews. While this topic is invoked mainly to denote the fact that gamblers may not be the most trustworthy folk, some of the details include a bit of haggling over whether people who who send their trained pigeons to steal other people’s pigeons can be considered as shysty as those who simply race pigeons for cash rewards. After a bit of back and forth, it is concluded that everyone involved in pigeon shenanigans are just as sleazy as dice players, who are banned by halakhah from serving as witnesses. The long and the short of it is that the Rabonim simply do not like the gambling.

When I first read Sanhedrin 25, I thought it was terrifically interesting, not because I had some investment in knowing whose testimony is considered worthy, nor because I’d just renovated the pigeon coop on top of my tenement. I was fascinated because it was an instance of the amoraim interfacing with the amkho. I have an abiding interest in the the amkho, those average, everyday Jews that make up the bulk of this freaky nation. These are the people you find on the margins of rabbinic discourse, those upon whom the rabbis meted out their rulings and punishments. Truth be told, I find these people much more interesting than either the rabbis or their fiddling with halakhah. Amazingly, in this discussion, the rabbis throw out some neat details about how pigeon racers would hit trees to make their pigeons go faster and how some people played a dice-like game with something called pispasin, a hardcore Jewish gambling habit that seems to gone the way of the dodo.

Unfortunately, Jewish traditional texts aren’t very amkho-friendly. The average Yosls and Yentas who smuggle their way into works produced by rabbinic elites generally appear because they somehow screwed up, did something the rabbis didn’t approve of and thus wound up being officially approbated, a fact they also often ignored. That fact notwithstanding, the amkho still appears to have retained a high regard for their rabbinic elites, in spite of the fact that they frequently disregarded rulings that interfered with anything they considered even remotely fun.

Take, for example, the body of rabbinic admonitions that trip their way from the gemara through 19th century responsa insisting that Jews refrain from attending theater and circus performances. Did any self-respecting Jew with tickets to whatever the 6th century version of Hamilton was ever say, “um, this isn’t permitted…we’d better not go.” This type of thing goes on for centuries. Sure, there’s a broad core of laws that most Jews stuck to, but, when it comes to matters of amusement or desire, the edges can get pretty fuzzy.

If you jump from the Talmudic period to the early 20th century (yes, I know this is ridiculous), one finds that the dynamic doesn’t change very much. The only real difference is that the rabbinic elite has lost much of its power and influence. Amkho still respects them, but they also still do what they want. One interesting factor is that there is now a forum where news of both the rabbis and the amkho begins to appear on a regular basis. This would be the Yiddish press, the first form of mass media in a Jewish language, a place where international and national news collided with Yiddish literature and criticism, where great essayists railed both in favor and against tradition, where pulp fiction sits alongside great literature, and where, among myriad other things, you can find a near endless supply of data on millions of tog-teglekhe yidn, everyday Jews who populated the urban ghettos of cities like New York and Warsaw. In a nutshell, the Yiddish press is a roiling and angry sea of words filled with astounding stories of all kinds of Jews, religious, secular and many who vacillate perilously between the two, aloft somewhere between modernity and tradition, taking bits of both, throwing it all in a pot and cooking it until it’s well done.

It is not at all uninteresting.

As a kind of wildly disjointed chronicle of Jewish life, Yiddish newspapers are an unparalleled resource on the pitshevkes, the tiny, yet fascinating details of Jewish urban immigrant life. Where else could one find out that Hasidim were a significant component of the Jewish audience at professional wrestling matches in Poland during the 1920s? Or that 50,000 Jewish mothers rioted against the public schools on the Lower East Side in 1906? Where could one discover that petty theft in Warsaw spiked annually just before Passover, when Jews were known to buy new clothes and linens? Is there a place you know of where one could find out that Jewish atheists antagonized religious Jews on Yom Kippur by walking around eating and smoking? Or that gangs of ultra-Orthodox Jews stalked the streets on Shabbos demanding people shut down their businesses? If you want to experience the knot of fury into which Jewish life was bound up, look no further than the Yiddish press.

Yiddish newspaper editors always knew where to find the juiciest stories and, for example, frequently sent journalists to cover goings-on in the Warsaw beyz-din. And it wasn’t because there were important cases being seen there, but because there was always some wild scandal blowing up in front of the rabbis that often ended up with litigants heaving chairs at one another. Whether it was some guy who thought it would be okay to marry two women and shuttle between them, or a woman who knocked out her fiancée’s front teeth after he refused to acknowledge that he had knocked her up. Like a Yiddish language Jerry Springer Show, brawls broke out in the rabbinate on a near daily basis during the 1920s and 1930s. The rabbis, of course, were mortified. But they kept at it. And the journalists of the Yiddish press were there to record.

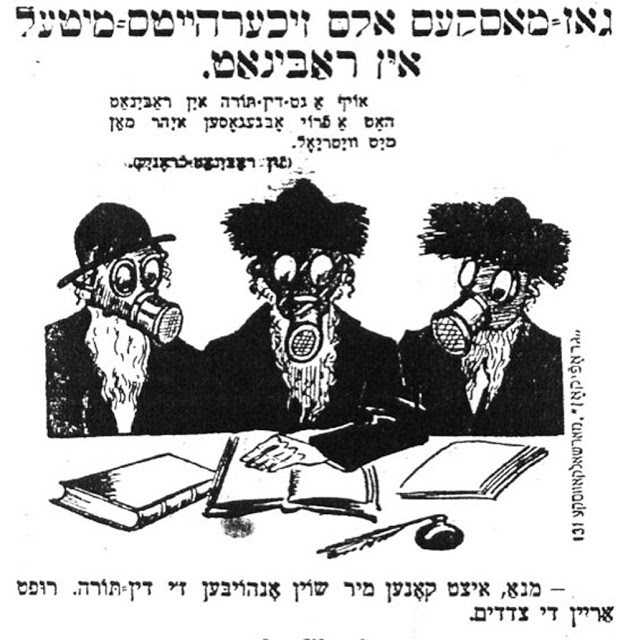

Captions (top, middle, bottom):

“Gas masks as a security measure in the Rabbinate.”

“A woman poured vitriol on her husband in a divorce case” (from the Rabbinate Chronicle)

“Thus can we now begin the case. Call in the two sides.”

It may be that you don’t want to know that there were Jewish criminals, drunks, prostitutes, imbeciles, and myriad other types that comprise the lowest echelons of society. But these small, often inconsequential matters that litter the pre-WWII Yiddish press comprise the details of a culture that has largely disappeared. Moreover, one can find a wealth of information on the amkho, who they were, how they lived, how they thought and spoke. This of course, begs the question: what do we want out of history? Do we only want to know about the rabonim, the manhigim, the writers, the artists, and the businesspeople? Or do we also want to peek into the lives of the average, the boring, the unsuccessful, the dumb, and the mean? Do we want a full picture of the Jewish world that was, or do we only want the success stories?

For my money, I want to know as much as I can about how Jews lived before World War II. Not everyone’s great grandfathers were kley-koydesh. In fact, most weren’t and it’s sheer fantasy to think that most Jews had extensive yeshiva educations. Most Yiddish-speaking Jews were poor, uneducated, and sometimes illiterate. Many of them did dumb things, made bad decisions, and wound up in big trouble. Clearly a shonde, they may not have the yikhes we want, but, also, we don’t get to choose. They may not be the best role models, but they are nonetheless integral to the Jewish story.