Rav Kook’s Attitude towards Keren Hayesod – United Israel Appeal

Kook’s Attitude towards Keren Hayesod – United Israel Appeal

Today is the yahrzeit of the Rav Eitam and Naama Henkin, who were cruelly murdered one year ago. May Rav Eitam’s important writings, surely with us only thanks to Naama’s support, be an aliyat neshama for both. Hy”d.

“It is well known that the person

who heads the above [body]” supports Keren Hayesod

What is the difference between Keren

Kayemet Le-Yisrael – the Jewish National Fund – and Keren Hayesod — the United

Israel Appeal?

The forgery in the 1926 public letter

The significance of supporting Keren

Hayesod

The halakhic letter of 1928

The joint declaration with Rav Isser

Zalman Meltzer

Conclusion

is well known that the person who heads the above [body]” supports Keren

Hayesod

philosophy of Rav Elĥanan Bunem

Wasserman, follower of the Ĥafetz

Chaim and Rosh Yeshiva of the Baranovich Yeshiva (Lithuania), and among the

most extreme of eastern European Torah leaders between the world wars in his

anti-Zionist approach, is still considered today as having significant

influence on the ideology concerning Zionism and the State of Israel prevalent

in the Hareidi community. In this respect he constitutes almost an antithesis

to the Chief Rabbi of Eretz Yisrael, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, in

whose philosophy religious Zionism found its main ideological support for its approach

and outlook.[1]

rare statement made by Rav Wasserman, aimed apparently at Rav Kook, has found

resonance with part of the Haredi public, and is used by them as justification

for rejecting Rav Kook and his teachings. In fact, we are not talking of a

direct reference, but of words that appear in a letter sent to Rav Yosef Tzvi

Dushinski, who took over Rav Yosef Ĥaim Zonnenfeld’s position as head of the Eidah Ĥareidit, on June

25, 1924:

Din with the Chief Rabbinate. It is well known that he who heads [the Chief

Rabbinate] has written and signed on a declaration calling on Jews to

contribute to Keren Hayesod. It is also known that the funds of Keren Hayesod

go towards educating intentional heretics. If that is the case, he who

encourages supporting this organization causes the public to sin on a most

terrible level. Rabbeinu Yona in Sha’arei

Teshuva explains the verse “The

refining pot is for silver, and the furnace for gold, and a man is tried by his

praise” (Prov. 27:21) as

meaning that in order to examine a person one must look at what he praises. If

we see that he praises the wicked, we know that he is an utterly wicked person,

and it is clear that it is forbidden to associate with such a person.[2]

far as Rav Wasserman was concerned, because the head of the Chief Rabbinate

publicized statements in which he called to support Keren Hayesod, which among

other activities, funded a secular-Zionist education system, he was causing the

public to sin and it was forbidden to be associated with him.[3]

it seems that Rav Wasserman’s sharp assertion is based on a factual error.[4]

According to Rav Kook’s son, Rav Z.Y. Kook, his father supported Keren Kayemet

Le-Yisrael, and called on others to support them, but his attitude towards Keren

Hayesod was completely different.

their behavior concerning religion and Judaism, [Rav Kook] later delayed giving

words of support to Keren Hayesod, and none of the entreaties and efforts of

Keren Hayesod’s activists could move him. In contrast, even though he continued

to constantly protest concerning those claims and complaints, he never

hesitated giving words of support to Keren Kayemet. None of the entreaties and

efforts of those who opposed Keren Kayemet could change this. On the contrary, with

his sacred fire, he increased his support and encouragement for Keren Kayemet, [considering

its projects as] a mitzvah of redeeming and conquering the Land.[5]

these words are correct, Rav Wasserman’s protest loses ground. In light of the

above we would have to say that Rav Wasserman’s sharp statement about Rav Kook

relies on the shaky basis (“It is well known…”) of rumors that were

widespread in certain localities in East Europe.[6]

However, precise research shows that despite Rav Z. Y. Kook’s clear testimony, for

which we will bring below explicit references from Rav Kook himself, Rav

Wasserman’s words were not just based on vague rumors alone. It turns out that

even while Rav Kook was alive, propaganda attempts were made to attribute to

him support for Keren Hayesod. In one case, at least, it was intentional fraud,

upon which it seems Rav Wasserman unwittingly based himself.

is the difference between Keren Kayemet LeYisrael – the Jewish National Fund –

and Keren Hayesod – the United Israel Appeal?

the case may be, the reader will ask: what is the difference between the Keren

Kayemet and the Keren Hayesod? Perhaps in Rav Wasserman’s opinion they both

were “abominations,” since both organizations were headed by “heretics”;

and even though Keren Kayemet did not deal with education, nevertheless it

enabled heretics to settle on its land. If that was the case even supporting Keren

Kayemet falls into the category of lauding the wicked, etc.! However, one

cannot ignore the fact that R. Wasserman was talking about Keren Hayesod in

particular, on the grounds that its funds were “going towards raising

intentional heretics” in the educational institutions – something not

relevant to the activity of Keren Kayemet. The Keren Kayemet was a veteran

institution, founded at the beginning of the century for very specific,

accepted goals – redeeming land from the hands of gentiles, whereas Keren

Hayesod was established at the beginning of the twenties in a very different

political reality, and its fields of activity were much broader. Rav Kook

himself, in a response from winter 1925 to the famous letter from four Hasidic

rebbes (Ger, Sokolov, Ostrovtza, and Radzhin) who had heard that “your

Honor is indignant over our opposition to giving aid to the Keren Kayemet and

Keren Hayesod,” and in which they explained their opposition, gave his

reasons in full for supporting the Keren Kayemet, and only the Keren Kayemet.[7] In an

earlier draft of his response, in his handwriting, preserved in his archive, he

explicitly notes the difference in his approach to the two organizations:

Keren Kayemet alone […] which is busy transferring land from the hands of

gentiles to Jewish possession, […] and for that I gave Keren Kayemet’s activists

a recommendation over the course of several years. This is not the case with

Keren Hayesod, which does not deal in redeeming land, but rather in settling it

and in matters of education. I have never yet given them a recommendation [and

will not do so] until the matter will, please God, be put right, and at least a

significant part of the funds will be assigned to settling Eretz Yisrael in the

way of our holy Torah.[8]

is indeed a large amount of information about the extensive relations that Rav

Kook had with Keren Kayemet, most of which involved continuous support for its tremendous

project of redeeming land, together with constantly keeping his eye on, and immediately objecting to, any deviation

from the way of the Torah that was perpetrated on its grounds.[9] On

the other hand, in all the writings of Rav Kook published till now, there are

only a few mentions of Keren Hayesod, and they show reservations in principle

from the organization.[10] Whoever

is fed by rumors and presents Rav Kook as one who “lends his hand to

evil-doers” without reservations, will anyway assume, “as it is

known,” that he similarly called for support of Keren Hayesod. In

contrast, for someone who knows about Rav Kook’s life story, his work, and his

letters, the idea that he would be capable of calling for support for an

organization which directly causes ĥilul Shabbat, secular education, and

so on, is utterly baseless. Even his support for Keren Kayemet was not

complete, but with conditions, restrictions, and even warnings attached. The

following are some salient examples that are sufficient to prove that if Keren

Kayemet had been involved in projects opposed to the spirit of the Torah — as

was the case with Keren Hayesod — Rav Kook would not have agreed to support it

either:

a letter to the chairman of Keren Kayemet, Menahem Ussishkin, from February 4,

1927, concerning violations of Shabbat in the Borokhov neighborhood located on

Keren Kayemet land (by the residents, not by Keren Kayemet itself), Rav Kook

warned them “that if they do not take the necessary steps to correct these

wrongdoings that have gone beyond all limits, I will be forced to publicize the

matter in an open letter, loud and clearly, to the whole Jewish People.”[11]

a letter to Tnuva from March 2, 1932, that was sent following a report

concerning ĥilul Shabbat on Kibbutz Mizra, Rav Kook announced that so

long as the kibbutz members did not mend their ways, their milk would be

considered as ĥalav akum (milked by a non-Jew) and Tnuva would be

forbidden from using it.[12]

a letter to Ussishkin from April 3, 1929, Rav Kook complained about the fact

that Keren Kayemet had started to publish literary pamphlets, “which are

not its subject matter. Money dedicated to the redemption of the Land was not

for literary purposes. Moreover, the essence of this literature damages its

image in public, spreading false views in direct opposition to the sanctity of our

pure faith […] I hope that these few words will have the correct effect, and

that the obstacle will be removed without delay, so that we will all together,

as one, be able to carry out the sacred work of redeeming the Land with the

help of Keren Kayemet Le-Yisrael.”[13]

forgery in the 1926 public letter

significant weight that Rav Kook’s position bore, over the years many attempts

were made by the supporters of Keren Hayesod to ascribe to him outright support

of the fund. The most prominent case occurred in the winter of 1926 (about a

year after the above-mentioned letter to the hasidic rebbes). Several months

previously the yishuv in Eretz Yisrael entered a severe economic crisis which

seriously hindered its development, causing unemployment of a third of the work

force, a decrease in the number of immigrants, and a steady flow of emigrants

from the country.[14] This

crisis, considered the worst experienced by the yishuv during the

British Mandate, was the first time that the impetus of the yishuv‘s

development, which had been increasing since the end of the First World War, was

brought to a standstill. Against the backdrop of this situation, the Zionist

leadership initiated a “special aid project of Keren Hayesod for the

benefit of the unemployed in Eretz Yisrael.” Because of the severity of

the situation, Rav Kook also volunteered to encourage contributions to improve

the economic situation in Eretz Yisrael, and when R. Moshe Ostrovsky (Hameiri)

left for Poland to help with the appeal, Rav Kook gave him a general letter of

encouragement for the Jews in eastern Europe.[15] At

the same time, on November 8, 1926, Rav Kook wrote a public letter calling for

support of the Zionist leadership’s initiative, in which he wrote, inter alia:

Diaspora, whose hearts and souls yearn for the building of Zion and all its

assemblies; beloved brethren! The hard times which our beloved yishuv in

the Land of our fathers is experiencing, brings me to raise my voice with the

call, “Help us, now.” Our holy edifice, the national home for which

the heart of every Jew holds great hopes, is now facing a temporary crisis

which requires the help of brothers to their fellow sufferers in order to

endure […] Therefore I am convinced that the great declaration which the

Zionist leadership is proclaiming throughout the borders of Israel, to make

every effort to come to the aid and relief of this crisis, will be heard with

great attention; and that, besides all the frequent donations for all the

general matters of holiness which our brothers wherever they live will give for

the sake of Zion and Jerusalem, all the sacred institutions will raise their

hands for the sake of God, His people, and His Land, to give willingly to the appeal

to relieve the present crisis, until the required sum will be quickly

collected.

the appeal was made through the organization of Keren Hayesod, Rav Kook avoided

mentioning the name of the fund because of his principled refusal to publicize

support for it (as he explained in the letter to the hasidic rebbes). The

version quoted above is what was published in the newspapers of Eretz Yisrael,

under the title “For the Relief of the Crisis.”[16]

However, amazingly, it becomes apparent that in the version published some

weeks later in Warsaw’s newspapers, the words “the Zionist

leadership” were changed in favor of the words “the head office of

Keren Hayesod,” and accordingly, the words were presented as nothing

less than “Rav Kook’s public letter in favor of Keren Hayesod“![17]

if we didn’t have any information other than the two versions of this public

letter, there is no doubt that the authentic version is the one published by

his acquaintances, the editors of Ha-Hed and Ha-Tor in Eretz

Yisrael, close to, and seen by Rav Kook. In contrast, when members of Keren

Hayesod circulated Rav Kook’s public letter among Poland’s newspapers, they were

not concerned that the author would come across the version they had published

in a remote location. They even had a clear interest to insert into Rav Kook’s

words a precedential reference to Keren Hayesod. Even if we only had before us

the east-European version of the letter, we could determine that foreign hands

had touched it. This is not only because of Rav Kook’s words in his letter to

the hasidic rebbes sent about a year earlier, but because of a letter that Rav

Kook sent to the heads of Keren Hayesod a few weeks prior to writing the public

letter. In this letter to Keren Hayesod he informs them in brief that he is

prevented from cooperating with the management of the fund or even visiting its

offices (!) until the list of demands that he presented them with, in the field

of how they conduct religious affairs, would be met. The background to this

letter is a request sent to Rav Kook on December 7, 1926, after the

inauguration of Keren Hayesod’s new building on the site of “the national

institutions” in Jerusalem. The directors of the head office of Keren

Hayesod wrote: “It would give us great joy, and would be a great honor if

our master would be so good as to visit our office – the office of the global

management of Keren Hayesod.”[18] In

reply to this request, Rav Kook wrote a letter – which is published here for

the first time – to the heads of Keren Hayesod, (Arye) Leib Yaffe and Arthur

Menaĥem Hentke:

office. I hereby inform you that I will be able to cooperate for the benefit of

Keren Hayesod, and I will, bli neder, also visit Keren Hayesod’s main

office, after Keren Hayesod’s management and the Zionist leadership will

fulfill my minimal demands concerning religious issues in the kibbutzim and in

education.

the course of the years there were, nevertheless, several opportunities when

Rav Kook came into contact with members of Keren Hayesod, mainly in connection

with matters of budgets for religious needs.[20]

However, as this letter illustrates, even such limited cooperation was

dependent, from Rav Kook’s point of view, on the demand to change the way the

fund conducted its matters with respect to religion.[21] What

were Rav Kook’s exact demands of Keren Hayesod, in order for it to be

considered as having “put things right” (as he wrote in his letter to

the hasidic rebbes), and to benefit from his support and cooperation? We can

clarify this from a document which is also being published here for the first

time. This document, whose heading is “Rav Kook’s answers” to Keren

Hayesod, was apparently written after the previous letter, in reply to a

question addressed to him by Keren Hayesod concerning his attitude towards

them. It was probably written against the backdrop of rumors that Rav Kook

forbade (!) support of Keren Hayesod.[22] We only

have a copy of the document in our possession, but it is written in first

person, meaning that Rav Kook wrote it himself, and the person who copied it

apparently chose to copy just the body of the letter without the opening and

end signature:

1. I

have never expressed any prohibition, God forbid, against Keren Hayesod. On the

contrary – I am very displeased with those who do so.

2. Concerning

my attitude towards the Zionist funds: my reply was that I willingly support

Keren Kayemet at every opportunity without any reservations. However,

concerning Keren Hayesod, at the moment I am withholding my letter in its

benefit until the Zionist management corrects major shortcomings that I demand

be put right, as follows:

a.

That nowhere in Eretz Yisrael will

education be without religious instruction, not just as literature, but as the

sacred basis of Jewish faith.

b.

That all the general religious needs be

immediately taken care of in every moshav and kibbutz. For example, shoĥet,

synagogue, ritual bath, and where a rabbi is necessary – also a rabbi.

c.

That there will be no public profanation

of that which is sacred in any of the places supported by Keren Hayesod, such

as ĥilul Shabbat and ĥag in public.

d.

That the kitchens, at least the general

ones, will be particular about kashrut.

e. That

all the details here which concern the residents of Keren Hayesod’s locations,

will be listed in the contract as matters hindering use of the property by the

resident, and which will give him benefit of the land only on condition that he

fulfills these basic principles.

And because I strongly hope that the management will

finally obey these demands, I therefore am postponing my support of Keren

Hayesod until they are fulfilled. I hope that my endeavors for the benefit of

settling and building our Holy Land will then be complete.

should be noted that these conditions are similar in essence to those that Rav

Kook set with Keren Kayemet. However, the latter’s dealings were with redeeming

the Land, in contrast to Keren Hayesod where the areas referred to in Rav

Kook’s demands were at the center of its activity. Therefore, as far as the

Keren Kayemet was concerned, Rav Kook did not give the fulfillment of his

demands as a basic condition for his cooperation and call for support; but he

certainly did so with regard to Keren Hayesod.[23]

the case may be, if R. Wasserman did indeed see the public letter of 1926,

without doubt he saw the falsified version published in the Polish newspapers,

and therefore he held on to the opinion that: “It is well known that he

who heads [the Chief Rabbinate] has written and signed on a declaration calling

on Jews to contribute to Keren Hayesod.”[24]

However, as has been clarified, these words have no basis.

significance of supporting Keren Hayesod

has been said Rav Kook was not prepared to support Keren Hayesod, which dealt

in education and such matters “until the matter will … be put right, and

at least a significant part” of the funds activities will be directed to

settling the Land according to the Torah. The words “at least a

significant part …” seem to give the impression that if a significant part

of the fund’s activity were directed to activity in the spirit of the Torah,

then Rav Kook would give his support even if another part were still directed

to secular education. However, in practice, there is no doubt that Rav Kook’s

demand was much stricter. In Keren Hayesod’s regulations it was determined that

only about 20% of its resources would be directed to education[25] (and

only a certain amount of that budget would be allocated to

“problematic” education) — and despite this fact Rav Kook refused to

call for its support. It must be emphasized that this policy in Keren Hayesod’s

regulations was strictly applied. An inclusive summary of the fund’s activity

between the years 1921-1930, indicates that 61.4% of its resources were

invested in aliya and settlement (aliya training, aid for refugees,

agricultural and urban settlement, housing, trade, and industry), 19.6% in

public and national services (security, health, administration), and only 19.0%

in education and culture – from which a certain part was allocated for

religious needs: education; salaries for rabbis, shoĥtim, and kashrut

supervisors; maintenance of ritual baths, eruvim, and religious

articles; aid for the settlements of Bnei Brak, Kfar Ĥasidim, etc.[26] In

light of this data, it seems that R. Wasserman’s claim against those who call

for support of Keren Hayesod, and his defining them as “utterly

wicked” people, is not essentially different from the parallel claim

against those who demand the paying of required taxes to the State – a claim

heard today only by extreme marginal groups within the Ĥaredi sector.

not surprisingly, it transpires that there were in fact some well-known rabbis

of that generation who did call to contribute to Keren Hayesod, despite the

problematic issues of some of its activity.[27] Just

several months before the publication of Rav Kook’s afore-mentioned public

letter, another declaration was published, explicitly calling for support of

Keren Hayesod, signed by more than eighty rabbis from Poland and Russia. Among

them were well-known personalities such as R. Ĥanokh Henikh Eigash, author of Marĥeshet;

R. Meshulam Rothe; R. Reuven Katz, and more.[28]

Moreover, in several locations, particularly in America, support of Keren

Hayesod was considered as consensus among the rabbis,[29] and

even Rav Kook’s colleague in the Chief Rabbinate, R. Ya’akov Meir, called for

support of Keren Hayesod.[30]

Would R. Wasserman have defined all of these scores of rabbis as evil ones

“who cause the public to sin on the most terrible level”?[31] Whatever

the case may be, it transpires that it was specifically Rav Kook who stands out

as being the most stringent among them, and he consistently agreed to publicize

support only for Keren Hakayemet. In the light of all the data detailed here,

one wonders whether R. Wasserman’s extreme words to R. Dushinski[32] were

only written in order to deter him from cooperating with the Chief Rabbinate

(which he strongly opposed), and perhaps this is the reason that he avoided

mentioning Rav Kook explicitly by name.[33]

halakhic letter of 1928

public letter of 1926 was indeed the only one in which Rav Kook’s words were

falsified in order to create support for Keren Hayesod. However, in the

following years, too, attempts were made to present what he had written as an

expression of direct support of Keren Hayesod. The element the two cases have

in common is that they were both published far from Rav Kook’s location. In 1928,

an announcement from the “Secretariat for Propaganda among the

Ĥaredim” was published in the Torah monthly journal Degel Yisrael,

published in New York and edited by R. Ya’akov Iskolsky. This secretariat

published a special letter from Rav Kook in Degel Yisrael, emphasizing

that the letter had not yet been publicized anywhere else. According to the

secretariat, the context in which the words were written was the following:

An

occurrence in a town in Europe, where the community demanded that all its

members contribute towards Keren Hayesod, and the opponents disputed

this before the government, and took the matter to court. The judges demanded

that the community leaders prove to them that the matter was done in accordance

to Jewish law, and on the basis of the above responsum (of Rav Kook) the

members of the community were acquitted.[34]

other words, according to those who publicized the Rav Kook’s letter, it was

written in order to help the heads of one European community to force all its

members to donate to Keren Hayesod. The problem is that examination of the

letter (see below) raises different conclusions. Similar to what appears above

(note 27) concerning the letter written by R. Meir Simĥa Ha-Kohen of Dvinsk,

here there is also no mention at all of Keren Hayesod. The explanations in the

letter are not relevant to the majority of Keren Hayesod’s projects, and the

letter only deals with clarifying the general virtue of settling Eretz Yisrael

and the obligation to support its inhabitants. Even the title prefacing the

letter only talks about “one community that agreed to impose a tax on its

members for the settlement and building of Eretz Yisrael,” without

mentioning that this was a tax specifically for Keren Hayesod. Towards the end

of the letter it is mentioned only that “the Zionist leadership in Eretz

Yisrael deals with many issues concerning settling the Land,” without any

specific reference to Keren Hayesod, even if the fund was the organization that

managed the appeal for the Zionist Organization. Thus, we again find that

whereas according to those that publicized the letter — the concerned parties —

the letter constitutes declared support for Keren Hayesod, in Rav Kook’s actual

words there is no mention of that.

letter, which as far as I know was never printed a second time, is brought here

in full:

on an individual the obligation to give charity for maintaining the settlement

of Eretz Yisrael, I hereby reply that there is no doubt in the matter, considering

that the halakha is that one forces a person to give charity, and makes

him pawn his property for that purpose even before Shabbat, as explained in Bava

Batra 8b, and as Rambam wrote in Hilkhot Matnot Aniyim 7:10:

concerning someone who does not want to give charity, or who gives less than

what is fitting for him, the court forces him until he gives the amount they

estimated he should give, and one makes him pawn his property for charity even

before Shabbat. The same is written in Shulĥan

Arukh, Yore Dei’a, 248:1-2. If

this is the case in all charities, all the more so is it the case concerning

charity for strengthening Eretz Yisrael, for this is explicit in Sifrei, and quoted in Beit Yosef, Yore

Dei’a, §251, that the poor of Eretz Yisrael have priority over

the poor outside the Land. And because one forces a person to give charity for

the poor outside the Land, it is clearly even more the case concerning charity

for strengthening the Land and its poor. The obligation to settle in Eretz

Yisrael is very great, as it says in the Talmud Ketubot 110b, and is brought by Rambam as a halakhic

ruling in Hilkhot Melakhim 5:12: A person should always live in Eretz

Yisrael, and even in a town where the majority are idol worshippers, rather

than live outside the Land, even in a town where the majority are Jews. In Sefer Ha-Mitzvot (mitzvah 4) Nachmanides wrote: that we were

commanded to inhabit the Land; “and this is a positive mitzvah for all

generations, and every one of us is obligated,” and even during the period

of exile, as is known from the Talmud in many places.

A great Torah principle is that all Jews are responsible for one another.

Therefore, those who are unable themselves to keep the mitzvah of living in

Eretz Yisrael, are obligated to help and support those who live there, and it

will be considered as though they themselves are living in Eretz Yisrael so

long as they do not have the possibility of keeping this big mitzvah

themselves. It is therefore obvious that any Jewish community can require an

individual to give charity for the benefit of settling Eretz Yisrael and

supporting its inhabitants; and G-d forbid that an individual will separate

himself from the community. Someone who separates himself from the ways of the

community is considered one of the worst types of sinners, as Rambam writes in Hilkhot

Teshuva 3:11. Just as the community must guide the individuals towards all

things good and beneficial, and any general mitzvah, thus must it ensure that

no individual separates himself from the community concerning matters of

charity in general, and all the more so concerning matters of charity relating

to Eretz Yisrael and support of its inhabitants, as I have written. No one can

deny that which is revealed to all, that the Zionist leadership in Eretz

Yisrael deals with al lot of matters concerning settling Eretz Yisrael, hence

it is clear that its income is included in the principle of charity for Eretz

Yisrael.

And as a sign of truth and justice, I hereby sign … Avraham Yitzĥak HaKohen

Kook

joint declaration with Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer

as the public letter of 1926 (in the version published in Poland) quickly came

to the notice of the zealots of Jerusalem, who rushed to claim that Rav Kook

supports “a baseless fund,” the same thing happened with the 1928

letter: following its publication under the above headline, the zealots rushed

to upgrade their accusations and to claim that Rav Kook ruled that one may

“force a person to give charity to Keren Hayesod” (see below).

fact brings us to yet another claim, raised only recently, that Rav Kook did

indeed sign on a declaration in support of Keren Hayesod. A few years ago,

Professor Menaĥem Friedman wrote about an event that occurred in winter 1930,

when the zealots of the Jerusalem faction of Agudath Israel, with Reb Amram

Blau at their head, came out with a particularly sharp street poster against

Rav Kook. The background to the attack was the joint declaration of Rav Kook,

R. Isser Zalman Meltzer, and R. Abba Yaakov Borokhov, that was published before

the convening of the 17th Zionist Congress in Basel, calling to the

attendants of the convention and its supporters to exert their influence to

prevent ĥilul Shabbat, etc; at the side of this request, writes Prof.

Friedman, was a “call to donate to Keren Hayesod.”[35]

in fact matters are not so clear at all. Prof. Friedman brings no support at

all for his words, and the only source that he brings concerning the event is

that same street poster that the zealots published. It seems that Prof.

Friedman never actually saw the said declaration, but rather assumed its

contents from the information that appears in parallel sources, such as the opposing

street poster, in which there is the claim that Rav Kook ruled that one may

“force people to give charity to Keren Hayesod,” but of course that

does not constitute an acceptable historical source.[36]

addition to this affair appears in a manuscript of R. Isser Zalman Meltzer,

which was published several years ago. This is a draft of a public announcement

from 1921, which shows that indeed there were those who understood that the

signature on the declaration meant support of Keren Hayesod (and other such

organizations) — but R. Meltzer clarifies that this was not the case:

Zionist funds, demanding that they do not support with their money those who

profane the Shabbat, and those who eat non-kosher food, I therefore declare

that my opinion is like it always has been: that so long as schools in Eretz

Yisrael that instill heretical ideas are supported by these funds, it is

forbidden to support them or give them aid in any way whatsoever. Those who

support and help them are destroying our holy Torah, and are ruining the yishuv.

I added my signature only to ask those who support those funds that at least

they should make every effort to influence those funds not to feed Jewish

people in kitchens that provide non-kosher food, and not to support those that

profane the Shabbat, etc.[37]

clarification was apparently written after reactions of amazement among some of

the Jerusalem public were voiced in the wake of the publication of the joint

declaration of R. Meltzer, Rav Kook, and R. Borokhov. From R. Meltzer’s words

it becomes clear that the joint declaration was not a call to support Keren

Hayesod, but a call to the supporters of the fund and to the attendants of the

Zionist Congress that they should anyway insist that their money should not be

used for unfitting purposes.[38]

Kook’s path was falsified many times, both during his lifetime and after his

death, sometimes unintentionally and sometimes intentionally. In what we have

written here, it is proven beyond all doubt that R. Elĥanan Wasserman’s claim

that Rav Kook called for the support of Keren Hayesod — a claim through which

he explained his opposition to cooperation between the Eidah Ĥareidit and the

Chief Rabbinate — is based on a mistake. The historical truth is that Rav Kook,

in his dealings with the institutions of the yishuv, more than once took

a more aggressive and stringent stand than did other rabbis of his generation,

as is expressed in the issue at hand.

light of this contrast, it is interesting that Rabbi Wasserman, as a youth, was

privileged to learn from Rav Kook for a while. In 1890 Rabbi Wasserman’s family

moved to Bauska (Boisk),

and five years later Rav Kook was appointed as rabbi of the town. At the time

Rabbi Wasserman was a student in the Telz Yeshiva, and when he returned home

during vacation, he would participate in the classes given by Rav Kook (See R.

Ze’ev Arye Rabbiner, “Shalosh Kehilot Kodesh,” Yahadut Latvia:

Sefer Zikaron [Tel Aviv, 1953], 268; Aharon Surasky, Ohr Elĥanan I [Jerusalem,

1978], 30).

Ma’amarim Ve-Igrot

I (Jerusalem, 2001), 153; previously in Kuntres Be-Ein Ĥazon (Jerusalem,

1969), 92. Concerning R. Wasserman’s dealings with the issues of the Jews in

Eretz Yisrael, we bring the words of R. Ĥaim Ozer Grodzensky, R. Wasserman’s

brother-in-law, which he wrote less than two months later in a reply to R.

Reuven Katz’s complaint regarding the open letter published by R. Wasserman to

Poalei Agudath Israel in Eretz Yisrael, calling on them not to accept help from

Zionist organizations: “I, too, am surprised at what [R. Wasserman] saw

that he publicized his personal opinion without consulting us, and I did not

know of it. He also exaggerated. The matters of the yishuv in Eretz

Yisrael cannot be compared to private matters in the Diaspora for several reasons,

and certainly it is impossible to give a ruling on such a serious matter from

afar without knowing the details…” (Aĥiezer – Kovetz Igrot [Bnei Brak, 1970], 1:299; see ibid., 200-1, a letter to Histadrut

Pagi, where the words are repeated. For R. Wasserman’s open letter and more

material on this subject, see Kovetz Ma’amarim Ve-Igrot I, 133-152).

statement is based on the words of Rabeinu Yonah Gerondi (Sha’arei Teshuva,

3:148), and R. Wasserman’s interpretation of them elsewhere (“Ikvete De-Meshiĥa,

§ 36, translated into Hebrew from the Yiddish by R. Moshe Schonfeld and

printed as a pamphlet in 1942, and in Kovetz Ma’amarim [Jerusalem 1963],

127-28). However, it seems that there is an essential difference between the

actual words of Rabeinu Yona and R. Wasserman’s interpretation (compare with a

parallel commentary of Rabeinu Yona to m. Avot 4:6, and the way his

words were interpreted by Rashbatz, “Magen Avot” 4:8, and R. Yisrael Elnekave,

Menorat Ha-Ma’or, Enlau edition, 310-11), and let this suffice. For an

example of a diametrically opposed position, see: R. Tzadok Ha-Kohen, Pri

Tzadik, Vayikra (Lublin 1922), 221.

Dadon, Imrei Shefer (Jerusalem, 2008), 273.

be-Elul” (Jerusalem, 1938) §24

(p.22). See also Siĥot Ha-Rav Tzvi Yehuda – Eretz Yisrael (Jerusalem,

2005), 84. On the other hand, R. Shmuel HaKohen Weingarten, who also heard from

Rav Tzvi Yehuda about his father’s refusal to call for support of Keren Hayesod,

pointed out an item in the newspaper Dos Idishe Licht (May 23, 1924),

according to which Rav Kook refused to support a proposal raised at the

American Union of Rabbis to boycott Keren Hayesod (Halikhot 33 [Tel

Aviv, Tishrei 1966], 27). Compare Rav Kook’s reasons for not waging a public

war against the Gymnasia Ha-Ivrit high school, despite his intense opposition

to the school (Igrot Ha-Re’iya II, 160-61).

of false rumors concerning Rav Kook was mentioned already in 1921 by the Gerrer

Rebbe, R. Avraham Mordechai Alter, in his well-known letter written on the

boat: “Outside Eretz Yisrael what is thought and imagined is different

from the reality. For according to the information heard, the Gaon Rav Kook was

considered to be an enlightened rabbi who ran after bribes. He was attacked

with excommunication and curses. Even the newspapers Yud and Ha-Derekh

sometimes published these one-sided reports. But this is not the correct way of

behavior – to listen to one side, no matter who it is…” (Osef

Mikhtavim U-Devarim [Warsaw, 1937], 68). R. Moshe Tzvi Neriya’s description

is typical: “…these news items even made their way into sealed Russia.

They said: “He’s close to the high echelons, and he has an official

position. This opinion excluded him from the usual description of a great Rav.

And then again it was said, ‘He’s close to the Zionists,’ and he was imagined

to be an ‘enlightened’ rabbi […] however, all those description and imaginations

completely melted away on seeing him.” (Likutei Ha-Re’iya [Kefar

Haro’eh, 1991], 1:13-14). An amazingly similar description was written by R.

Yitzchak Gerstenkorn, founder of Bnei Brak: “I imagined Rav Kook, of

blessed memory, as a modern rabbi […] and how amazed I was, on my first visit

to Rav Kook, when I saw before me a sacred, pious person, few of whom live in

our generation…” (Zikhronotai al Bnei Brak I [Jerusalem, 1942],

74).

la-Re’iya, 303-306. See also his 1923 declaration in support of Keren

Kayemet in which he emphasizes that “it is intended only for redemption of

the Land” (Raz, Malakhim ki-Venei Adam [Jerusalem, 1994], 238) —

meaning, not for educational and other such purposes as those of Keren Hayesod.

In this connection it should be noted that there was sometimes tension between

Keren Kayemet and Keren Hayesod because of the impression created that the

latter also dealt in redeeming lands (see Protokolim shel Yeshivot Ha-Keren

Kayemet Le-Yisrael, Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem, 4:109, 498/33 —

protocols from March 31 and July 7, 1922. See also the joint agreement of the

two funds, Ha-Olam 10:14 [January 27, 1921], 16). In order to illustrate

the Keren Kayemet’s well-established status among substantial sections of the

rabbinical world, we will refer to the 32nd annual convention of the

Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada, 1937. In the second

section of the convention’s resolutions it states: “The Union of Rabbis

imposes a sacred debt on all Orthodox Jews who will lend generous support to

Keren Kayemet Leyisrael.” It should be noted that the majority of

America’s great rabbis of the time participated in this convention (see Ha-Yehudi

2:10 [New York, Iyar 1927], 195. A similar resolution was made in previous

conventions; see, for example, HaPardes 5:3 [Sivan 1931], p. 31, § 7; HaPardes 6:3 [Sivan 1932], p.

25, § 5-8).

quoted by R. Yaakov Filber, Kokhav Ohr (Jerusalem, 1993), 21-22 (Slight

changes in style have been made according to a photocopy in my possession).

Negatives statements about Keren Hayesod were omitted from the response that

was actually sent, and only the positive statements about Keren Kayemet were

included. R. Filber posits that, based on the letter that Rav Kook sent to his

son, Rav Z. Y. Kook, about a week later (ibid.), the reason for the omission

was Rav Kook’s concern that the negative sentences might be used as a means to

attack the Zionist funds in general. In my opinion, taking into account Rav

Kook’s style, it is unlikely that he had such a concern, but rather the omission

is probably connected to his wish not to take part in a public boycott of Keren

Hayesod (see above, note 5).

Goutel, “Hilkhot Ve-Halikhot Ha-Keren Ha-Kayemet Le-Yisrael Ve-Haĥug Ha-Hityashvuti

Be-Ma’arekhet Hitkatvuyotav shel Ha-Rav Kook,” Sinai 121 (1998),

103-115; Ĥaim Peles, “Teguvotav shel Ha-Rav A. Y. Kook al Ĥilulei Ha-Shabat

al Admat Ha-Keren Ha-Kayemet Le-Yisrael,” Sinai 115 (1995),

180-186; see also Rav Kook, Ĥazon Ha-Geula (Jerusalem, 1937), 220-230;

ibid., 33-34, et seq. (I have expanded on the topic of Rav Kook’s relationship

with the Keren Kayemet elsewhere).

from winter 1924 to R. Dov Arye Leventhal of the Union of Rabbis, about his

trip to America, Rav Kook writes that one of the questions that his trip

depends upon is “whether there will not be a tendency to confuse his

support for this [the Union of Rabbis] with Keren Hayesod” (Igrot Ha-Re’iya

IV (Jerusalem 1984), 177. In a letter from winter 1925 to R. Akiva Glasner of Klausenburg,

he calls on him to make use of “the Zionist funds of Keren Hayesod”

for purposes such as sheĥita and ritual baths in a settlement of

Transylvanian immigrants in Eretz Yisrael. He comments that when all is said

and done, in most places the donors are religious Jews; but of course he should

ensure that everything is done according to the Torah (ibid., 216).

115 (1995), 181; the full letter was printed in Mikhtavim Ve-Igrot Kodesh

(ed. R. David Avraham Mandelbaum, New York, 2003), 588. Here, as in the third

example (see below), Rav Kook hints that if they do not take the necessary

steps, he will stop supporting the Keren Kayemet, and will even publicize the

matter.

115 (1995), 183

Zuriel, Otzarot Ha-Re’iya I (Rishon Lezion, 2002), 487.

Dan Giladi, Ha-Yishuv Bi-Tekufat Ha-Aliya Ha-Revi’it: Beĥina Kalkalit U-Politit

(Tel Aviv, 1973), 171-192. The cause of the crisis was twofold: on the one

hand, the especially large amount of new immigrants in the two years prior to

the crisis, for which the economy was unprepared; on the other hand, the severe

limitations that the Polish government enforced on taking money out of the

country (in an attempt to fight the hyperinflation of the value of the zloty),

which harmed both the donations to Eretz Yisrael, and the capability of the new

immigrants to bring their possessions with them to Eretz Yisrael.

R. Ostrovsky’s trip see Ha-Zefira 66:30 (February 4, 1927), 8. For the

blessings for success that he received from R. Yeĥiel Moshe Segalovitz, head of

the Mława rabbinical court, see ibid. 66:34 (February 9, 1927), 3. Rav

Kook’s letter to Polish Jewry was published in Ha-Olam on March 4, 1927,

and again in Zuriel, Otzarot Ha-Re’iya II (1998 edition), 1075.

Ha-Hed, Kislev 1926, p.12, and the weekly Ha-Tor 7:16 (November

19, 1926), front page. This version was printed later in Ĥazon Ha-Geula,

180. The version quoted here is based on minor corrections of mistakes that

appeared in one of the sources. In the description attached to the public

letter in Ha-Hed the following was written: “In honor of Keren

Hayesod’s special aid program for the benefit of the unemployed in Eretz

Yisrael, Rav Kook published a special public letter….”

65:50 (Warsaw, November 29, 1926), 3. In the description attached to the public

letter it said: “On 2 Kislev [November 8, 1926), the Chief Rabbi of Eretz

Yisrael, Rav A.Y. Ha-Kohen Kook sent the following public letter to the head

office of Keren Hayesod….” A few days later the letter was also published

in Ha-Olam 14:50 (London, December 3, 1926), 944, with the same headline

and description as in Ha-Zefira, but without the insertion of

“Keren Hayesod” in the body of the letter; see also Ha-Olam

14:48 (December 19), 906, where it was reported that “Rav Kook published a

public letter to world Jewry to aid Keren Hayesod, thereby easing the crisis in

Eretz Yisrael.”

Archives, KH421036. As is explained in this file, Rav Kook’s colleague, R. Y.

Meir, visited the offices of Keren Hayesod.

the letter in the possession of R. Ze’ev Neuman, to whom I am most grateful. It

should be noted that Leib Yaffe was a relative of Rav Kook: his paternal

grandfather, R. Mordechai Gimpel Yaffe, was Rav Kook’s paternal grandmother’s

brother. Nevertheless, at the opening of the letter, Rav Kook does not show any

family sentiment, but starts with a completely neutral tone.

before the above letter, in 1925, Rav Kook, together with other rabbis,

participated in a meeting with Keren Hayesod where sums allocated for religious

needs, and other allocation options, were decided upon (Yehoshua Radler-Feldman

[R. Binyamin], Otzar Ha-aretz [Jerusalem, 1926], 72-73; see also note 10

above).

should note the letter of both the chief rabbis from March 27, 1927 – about two

months after the above letter – which was sent, among others, to the secretary

of Keren Hayesod, Mordechai Helfman, with the demand to prevent the profanation

of Shabbat and kashrut in settlements located on the land of Keren Kayemet, or

that are supported by Keren Hayesod. In his reply from March 30 (quoted in

Motti Ze’ira, Keru’im Anu [Jerusalem, 2002], 172), Helfman justified

himself saying: “The management of Keren Hayesod is only a mechanism for

collecting money […] We are, of course, ready to help in [attempting to] have

moral influence, and we hereby promise his honor, that we will use our

influence at every opportunity to emphasize that which is wrong.”

can be found in the Central Zionist Archive KH1/220/2. I am grateful to Mr.

Yitzĥak Dadon, who made me aware of the document’s existence and gave me a

photocopy. Most of the demands in this document were repeated, with different

emphases, in a declaration publicized by Rav Kook in the spring of 1931 (see

note 37 below).

Kook repeated in this letter that he was not prohibiting support of Keren

Hayesod, later, when in 1932 the Jewish Agency did not fulfill its promise to

transfer an allocated sum for religious matters, Rav Kook protested the matter

in a sharp letter in which he warned that if at least part of the promised sum

was not transferred, he would be forced to turn to the rabbis in America and to

members of Mizrachi in Poland, with the demand to prevent support of the Keren

Hayesod appeal (letter from April 6, 1932, Central Zionist Archive

S255894-419).

about Rav Kook’s supposed support of Keren Hayesod, based on the east-European

version of the public letter, quickly reached Rav Kook’s opponents in Eretz

Yisrael and even in America. In a letter from December 29, 1926, Meir

Heller-Semnitzer, one of the most extreme zealots in Jerusalem (around whom,

that same summer, a major scandal erupted, concerning a harsh declaration that

he published against the Gerrer Rebbe and Rav Kook), informed Reb Zvi Hirsch

Friedman of New York (a distinguished zealot himself who, a year previously, had

been expelled from the Union of Rabbis in America because of attacks against

Rav Kook that he had published in one of his books), that Rav Kook issued a

proclamation calling for support of “the baseless fund” [play on words:

yesod means base]. See Friedman, Zvi Ĥemed – Mishpati im

Dayanei Medinat Yisrael (Brooklyn, 1960), 67.

Trunk pointed out already in 1921 (see note 27 below).

Hayesod Be-mivĥan Ha-zeman” in Luaĥ Yerushalayim – 5706 (Jerusalem,

1945), 259-268; see also Otzar Ha-aretz, 70-76.

connection it is customary to mention R. Meir Simĥa Ha-Kohen of Dvinsk, author

of Ohr Same’aĥ, who acceded to the request of an emissary of the World

Zionist Organization in preparation for the appeal of Keren Hayesod in Latvia,

and wrote his famous letter calling for support of the yishuv in Eretz

Yisrael (printed in Ha-Tor, 3, 1922, and also in R. Ze’ev Arye Rabiner, Rabeinu

Meir Same’aĥ Kohen [Tel Aviv, 1967], 163-165, et al.). However, even

though the historical context involves the Keren Hayesod, the letter itself

deals with general support of settling Eretz Yisrael, and contains no explicit

mention of Keren Hayesod or any other Zionist organization. Hence it is

difficult to see in the letter a ruling concerning the fundamental question of

whether to support Keren Hayesod despite the fact that part of its budget goes

towards secular education. The same applies to a similar letter written in the

same year and in the same connection by R. Eliezer Dan Yiĥye of Lucyn (See Otzar

Ha-aretz, 84-86). In contrast, R. Yitzĥak Yehuda Trunk of Kotnya, the

grandson of the author of Yeshu’ot Malko and one of the rabbis of the

Mizrachi movement in Poland, wrote a detailed letter in the same year,

explicitly calling for support of Keren Hayesod. He wrote at length rejecting

the arguments against contributing to the fund (See Sinai 85 [Nisan-Elul 1979],

95-96). See also in the following footnotes.

Ha-aretz, 78-82. It should be added that the Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv (later

the Rishon le-Tziyon), R. Ben-Tziyon Ĥai Uziel, participated, himself, in the

activity of Keren Hayesod (see his books, Mikhmanei Uziel IV (Jerusalem,

2007) 31-32, 283-284, and in vol. VI, 297-299, et al.), as did R. Ostrovsky (as

mentioned above), and others.

Ha-Olam (18:46 [London, November 11, 1930], 911) in honor of Keren

Hayesod’s tenth anniversary, “the declaration of Eretz Yisrael’s rabbis

concerning Keren Hayesod” from September 1930, was published. Hundreds of

rabbis signed the declaration, the majority from America, and others from Eretz

Yisrael, Europe, and Eastern countries. The declaration included an explicit

call to strengthen Keren Hayesod, “which for the last ten years has borne

on its shoulders the elevated task of building our sacred inheritance, and

faithfully supporting all projects that bring us close to that great aim.”

It seems that there is not one well-known rabbi who was active in the Union of

Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada who did not sign this

declaration: R. Yehuda Leib Graubart, R. Elazar Preil, R. Ĥaim Fischel Epstein,

R. Yosef Kanowitz, R. Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, R. Eliezer Silver, R. Ze’ev Wolf

Leiter, R. Ĥaim Yitzĥak Bloch, R. Yehuda Leib Salzer, etc., etc. (nevertheless,

in light of the scope and rare variety of the signatories, one wonders whether

this was a declaration approved by majority vote at the conference of the Union

of Rabbis, such that the weight of the opponents was not reflected, and

therefore the names of all the Union’s members were given as signatories).

Ha-aretz, 77, his letter from December 8, 1925 calling for support of Keren

Hayesod. See note 18, and more below.

interesting fact in this connection is that R. Wasserman’s relative by marriage

from 1929 (the father-in-law of his son R. Elazar Simĥa), R. Meir Abowitz, head

of the rabbinical court of Novardok and author of Pnei Meir on Talmud

Yerushalmi, not only was an avowed member of the Mizrachi movement, and in

1923 even signed a call to join the movement (see Encyclopedia of Religious

Zionism I [Jerusalem, 1958], columns 1-2), but also was one of the

signatories on the aforementioned declaration in favor of Keren Hayesod! (Otzar

Ha-aretz, 81). The fact that R. Wasserman was involved in R. Abowitz’s

younger daughter’s marriage, is testimony to the good relationship between the

families (see R. Wasserman’s daughter-in-law’s testimony in the photocopied

edition of Pnei Meir on the tractate Shabbat [USA, 1944], at the end of

the introduction. R. Abowitz’s letters to his son-in-law are published at the

end of R. Wasserman’s Kovetz Shiurim II [Tel Aviv, 1989], 117-119).

worthwhile comparing these words with R. Yosef Ĥaim Zonnenfeld’s moderate

language in a letter to his brother written in 1921, in which he gives the

benefit of the doubt to the donors of Keren Hayesod: “Those naïve ones,

who contribute to Keren Hayesod out of pure love in order to aid in the

establishment of the settlement in our holy Land, certainly have a mitzvah. I

do not know to what purpose they will actually put the money of Keren Hayesod,

but if it is given into faithful hands, who will use it honestly for settling

the Land, this is anyway a big mitzvah. However, as has been said, it must be

in such hands that will use it for building and not for destruction […] ‘and

because of our sins we were exiled from our Land'” (translated from

Yiddish, S.Z. Zonnenfeld, Ha-ish al Ha-ĥoma III [Jerusalem, 1975], 436).

Ya’akov Meir, who explicitly supported Keren Hayesod, was also one ” who

heads the above [i.e. the Chief Rabbinate],” nevertheless, R. Wasserman’s

words are taken to be addressed specifically to Rav Kook. On the other hand, it

is interesting that in a letter that R. Wasserman wrote to his brother on July

30, 1935, the following sentence appears: “What is Rav Kook’s malady, and

how is he feeling now?” (Kovetz Ma’amarim Ve-igrot II, 124).

Yisrael 2:11 (New York, December 1928), 12-13 (the emphasis is mine). The date

of the secretariat’s letter is April 26, 1928.

“Pashkevilim U-moda’ot kir Ba-ĥevra Ha-Ĥareidit,” in Pashkevilim

(Tel Aviv, 2005), 20. See also his book Ĥevra Va-dat (Jerusalem, 1978),

337.

year, October 1930, in an issue devoted to the tenth anniversary of Keren

Hayesod, a declaration from Rav Kook was printed under the heading

“Mi-ma’amakei Ha-kodesh,” in which a process of awakening in the

country among the people and the new yishuv is described, together with

a call to base activities on sanctity and to unite (Ha-Olam 18:45

[November 2, 1930], 900). Here, too, there is no explicit mention of Keren

Hayesod or any other organization, even though explicit calls by other

personalities for support of the fund were published close to his declaration

(See also an additional article by Rav Kook, (Ha-Olam 18:47 [November

18, 1930], 926).

Ve-Igrot Kodesh, 624. The date of R. Meltzer’s signature on the declaration

is February 18, 1921. He writes using the plural form: “schools … are

supported by these funds,” but in fact only Keren Hayesod referred funds

to educational institutions, such that his main opposition was actually

directed against it in particular, and not against Keren Hakayemet (see next

note). For the moment I have been unable to locate the call mentioned in his

words, which Prof. Friedman dealt with, however it is probably a very similar

declaration to the one published in Ha-Hed, April 1931 (and again in Otzarot

Ha-Re’iya II, 426), in which Rav Kook calls, in preparation for the

“coming Zionist Congress” to present a series of demands in the field

of religion, which have to come together with “material fundraising”

and aid to build up the country. It is superfluous to note that there is no

mention of Keren Hayesod in the declaration, as well as to no other official

institution.

see a similar public letter that the three rabbis, Rav Kook, R. Meltzer, and R.

Borokhov, together with R. Yaakov Meir, published in 1929, calling to the heads

of the Zionist organizations “to immediately send a last warning to the

kibbutzim and moshavot supported by you, that if they do not stop

profaning our religion, and everything sacred, you will stop your support of

them altogether. If our words are not obeyed by you, we will unfortunately be

forced to wage a defensive war against these destroyers of our People and our

Land […] even though this will harm the funds which support the new yishuv”

(printed in Ha-Tor 9:37 [August 9, 1929], and again in Keruzei

Ha-Re’iya [Jerusalem, 2000], 90)

Jews in Wonderland

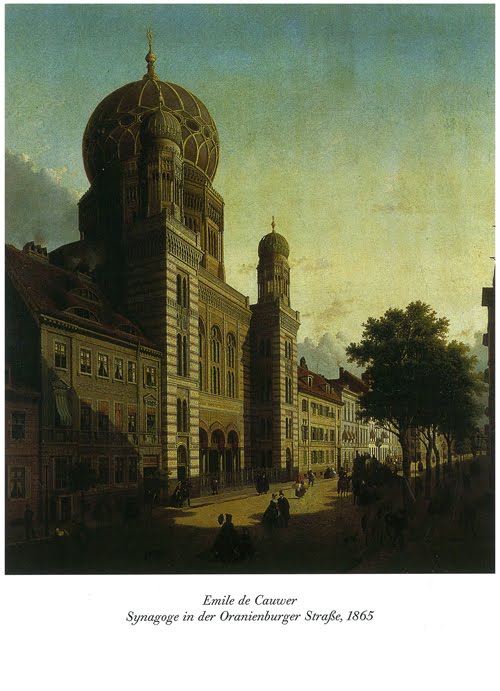

in similar terms. In 1820, a young Prussian-Jewish lawyer named Eduard Gans applied to the government for permission to establish an association dedicated to the study of Jewish history and culture. In his application Gans invoked the Jews of Spain:

closest union with Arab civilization.”

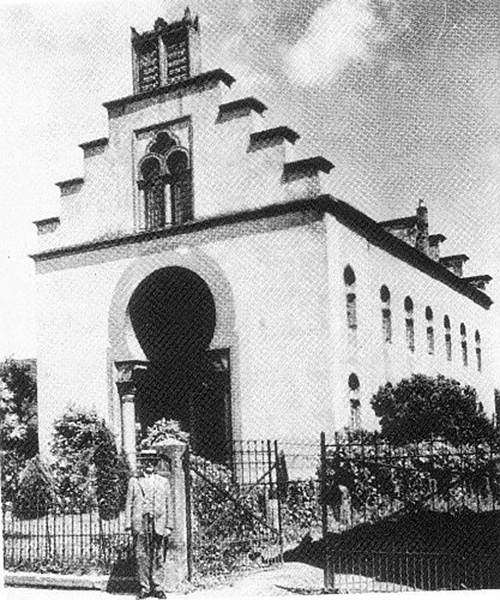

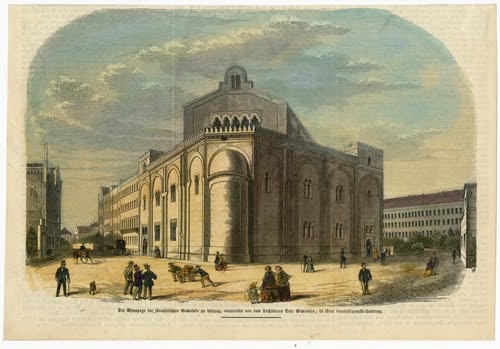

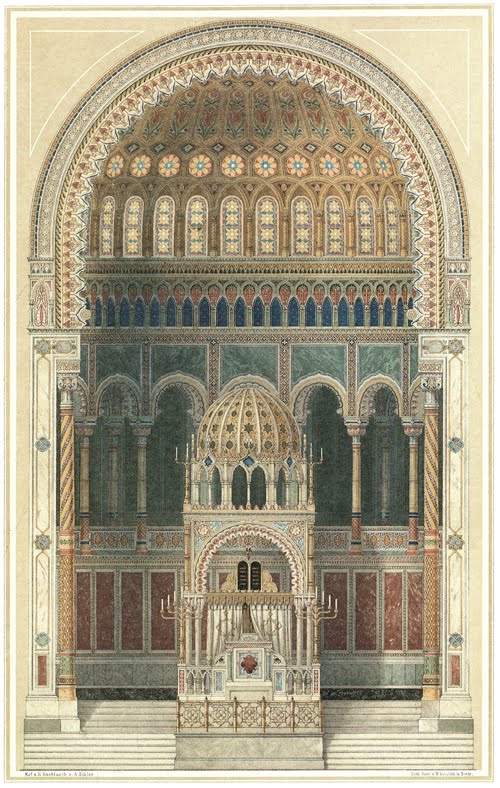

the oriental character of the building was unmistakable given the large horseshoe-arched entrance and Islamic style-windows that ran along either side of the synagogue and were modeled on those found on thirteenth and fourteenth century North African and Spanish mosques.

characteristic. Judaism adheres with unshakable reverence to its history; its

laws, its customs and practices, the organization of its ritual; in short, its

entire essence lives in its reminiscences of its motherland, the Orient. It is

those reminiscences that the architect must accommodate should he wish to

impress upon the building a typical [Jewish] stamp.”[2]

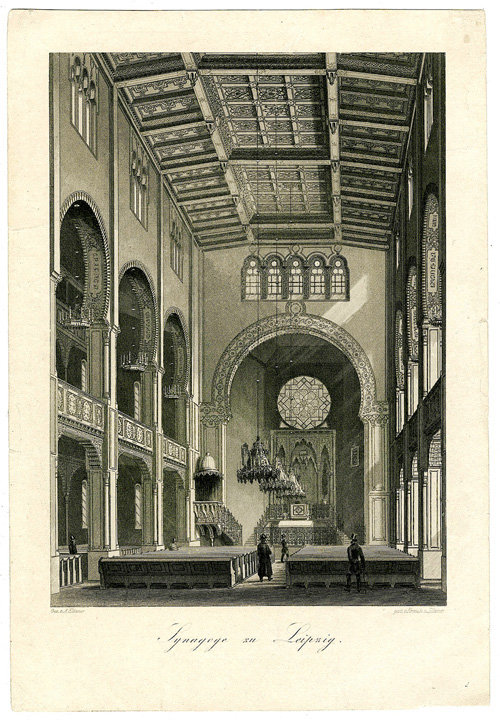

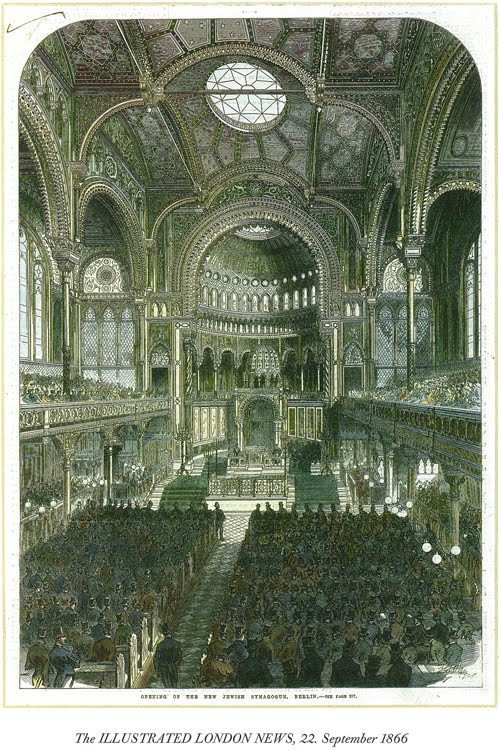

remained until it was over. The scene was perfectly novel to me, & most

interesting. The building itself is most gorgeous, almost the whole interior

surface being gilt or otherwise decorated—the arches were nearly all

semi-circular, tho’ there were a few instances of the shape sketched here—the

east end was roofed with a circular dome, & contained a small dome on

pillars, under which was a cupboard (concealed by a curtain) which contained

the roll of the Law: in front of that again a small desk facing west—the latter

was only once used. The rest of the building was fitted up with open seats. We

followed the example of the congregation in keeping our hats on. Many men, on

reaching their places, produced white silk shawls out of embroidered bags,

& these they put on square fashion: the effect was most singular—the upper

edge of the shawl had what looked like gold embroidery, but was probably a

phylactery [sic].

These men went up from time to time & read portions of the lessons. What

was read was all in German, but there was a great deal chanted in Hebrew, to

beautiful music: some of the chants have come down from very early times,

perhaps as far back as David. The chief Rabbi chanted a great deal by himself,

without music. The congregation alternately stood & sat down: I did not

notice anyone kneeling.”[3]

Text Manipulation on the Left – A Recent Incident

The Meaning of the Word Hitpallel (התפלל)

Meaning of the Word Hitpallel (התפלל)

Mitchell First[1]

appears in Tanakh that התפלל connotes praying. But what was the

original meaning of this word? I was always taught that it meant something like

“judge yourself.” Indeed, the standard ArtScroll Siddur (Siddur Kol Yaakov) includes the following in its introductory

pages: “The Hebrew verb for praying is מתפלל;

it is a reflexive word, meaning that the subject acts upon himself. Prayer is a

process of self-evaluation, self-judgment…”[2]

sites on the internet for the definition that was offered for hitpallel and mitpallel, I invariably

came up with a definition similar to the above. Long ago, Rabbi S. R. Hirsch

(d. 1888) and R. Aryeh Leib Gordon (d. 1912) also gave definitions that focused

on prayer as primarily an action of the self.[3]

interpretation offered by some modern scholars, one based on a simple insight

into Hebrew grammar. This new and compelling interpretation has unfortunately

not yet made its way into mainstream Orthodox writings and thought. Nor has it

been given proper attention in academic circles. For example, it did not make

its way into the widely consulted lexicon of Ludwig Koehler and Walter

Baumgartner.[4] By sharing this new interpretation of התפלל,

we can ensure that at least the next generation will understand the origin of this critical word.

——

are two issues involved in parsing this word: 1) what is the meaning of the

root פלל? and 2) what is the import of the hitpael stem, one that typically implies

doing something to yourself?

regard to the root פלל, its meaning is

admittedly difficult to understand. Scholars have pointed out that the other

Semitic languages shed little light on its meaning.[5]

we look in Tanakh, the verb פלל is found 4 times:[6]

seems to have a meaning like “think” or “assess” at Genesis 48:11: re’oh fanekha lo filalti…(=I did not

think/assess that I would see your face).[7]

seems to have a meaning like “intervene” at Psalms 106:30: va-ya’amod Pinḥas va-yefalel, va-teatzar ha-magefah (=Pinchas

stood up and intervened and the plague was stopped).[8]

seems to have a meaning like “judge” at I Sam. 2:25: im yeḥeta ish le-ish u-filelo elokim…(If a man sins against another

man, God will judge him…).[9]

also appears at Ezekiel 16:52: את שאי כלמתך אשר פללת לאחותך גם (= You also should bear your own shame that you pilalt to your sisters). The sense here is difficult, but it is

usually translated as implying some form of judging.

I would like to focus on in this post, however, is the import of the hitpael stem in the word התפלל.

Most students of Hebrew grammar are taught early on that the hitpael functions as a “reflexive” stem,

i.e., that the actor is doing some action on himself. But the truth is more

complicated.

source I saw counted 984 instances of the hitpael

in Tanakh.[10] It is true that a

large percentage of the time, perhaps even a majority of the time, the hitpael in Tanakh is a “reflexive” stem.[11] Some examples:

oneself”; the verb יצב is in the hitpael 48 times in Tanakh (e.g., hityatzev)

oneself”; the verb חזק is in the hitpael 27 times in Tanakh (e.g., hitḥazek)

oneself”; the verb קדש is in the hitpael 24 times in Tanakh (e.g., hitkadesh)

oneself”; the verb טהר is in the hitpael 20 times in Tanakh (e.g., hitaher)

ways as well. For example:

Genesis 42:1 (lamah titrau), the form

of titrau is hitpael but the meaning is likely: “Why are you looking at one

another?” This is called the

“reciprocal” meaning of hitpael.

Another example of this reciprocal meaning is found at II Chronicles 24:25 with

the word hitkashru; its meaning is

“conspired with one another.”

root הלך appears in the hitpael 46 times in Tanakh,

e.g., hithalekh. The meaning is not

“to walk oneself,” but “to walk continually or repeatedly.” This is called the

“durative” meaning of the hitpael.

There are many more durative hitpaels

in Tanakh.[12]

let us look at a different word that is in the hitpael form in Tanakh: התחנן. The root here is חנן which means “to be gracious” or “to show favor.” חנן

appears in the hitpael form many

times in Tanakh (התחנן, אתחנן, etc.). At I Kings 8:33 we even have a hitpael of פלל

and a hitpael of חנן adjacent to one another:

והתחננו והתפללו. If we are constrained to view התפלל as doing something to yourself, then what

would be the meaning of התחנן? To show favor to yourself? This

interpretation makes no sense in any of the contexts that the hitpael of חנן

is used in Tanakh.

as recognized by modern scholars, the root חנן

is an example where the hitpael has a slightly different meaning: to make

yourself the object of another’s action.

(This variant of hitpael has been

called “voluntary passive” or “indirect reflexive.”) Every time the root חנן is used in the hitpael, the actor is asking another

to show favor to him. As an example, one can look at the beginning of parshat va-et-ḥanan. Verse 3:23 states

that Moshe was אתחנן to God. אתחנן

does not mean that “Moshe showed graciousness to himself.” Rather, he was

trying to make himself the object of God’s

graciousness.

us now return to our issue: the meaning of התפלל.

Most likely, the hitpael form in the

case of התפלל is doing the same

thing as the hitpael form in the case

of התחנן: it is turning the word into a voluntary

passive/indirect reflexive.[13] Hence,

the meaning of התפלל is to make oneself the object of God’s פלל (assessment, intervention, or judging). This is a much

simpler understanding of התפלל than the ones that

look for a reflexive action on the petitioner’s part. Once one is presented

with this approach and how it perfectly parallels the hitpael’s role in התחנן,

it is very hard to disagree.[14]

Additional Comments

is interesting to mention some of the other creative explanations for התפלל that had previously been proposed (while

our very reasonable interpretation was overlooked!):

root is related to a root found in Arabic, falla,

which means something like “break,” and reflected an ancient practice of

self-mutilation in connection with prayer.[15] Such a rite is referred to at 1

Kings 18:28 in connection with the cult of Baal (“and they cut themselves [=va-yitgodedu] in accordance with their

manner with swords and lances, until the blood gushed out upon them”).[16]

oneself during prayer.[17]

root, but was a later development derived from a primary noun תפלה. In this approach, one could argue that התפלל is not even a hitpael.

(This approach just begs the question of where the word תפלה

would have arisen. Most scholars reject this approach because תפלה does not look like a primary noun. Rather, it looks like a noun

that would have arisen based on a verb such as פלל

or פלה.)

There are other examples in Tanakh of

words that have the form of hitpael

but are either voluntary passives (like התפללand התחנן)

or even true passives, as the role of the hitpael

expanded over time.[18] Some examples:[19]

37:35: va-yakumu khol banav ve-khol

benotav le-naḥamo, va-yemaen le-hitnaḥem…(The

meaning of the last two words seems to be that Jacob refused to let himself be

comforted by others or refused to be comforted; the meaning does not seem to be

that he refused to comfort himself.)

13:33: ve-hitgalaḥ (The

meaning seems to be “let himself be shaved by others.”)

23:9: u-va-goyim lo yitḥashav

28:68: ve–hitmakartem sham

le-oyvekha la-avadim ve-li-shefaḥot… (It is unlikely that the meaning is

that the individuals will be selling themselves.)

92:10: yitpardu kol poalei

aven (The evildoers are not

scattering themselves but are being scattered.)

30:29: ke-leil hitkadesh ḥag…(The holiday is not sanctifying

itself.)

31:30: ishah yirat Hashem hi tithalal

3:8: ve-yitkasu sakim ha-adam ve-ha-behemah… (Animals

cannot dress themselves!)

II Kings 8:29 (and similarly II Kings

9:15, and II Ch. 22:6): va-yashav Yoram

ha-melekh le-hitrape ve-Yizre’el… (The

meaning may be that king Yoram went to Jezreel to let himself be healed by

others or to be healed.)

precise role of the hitpael is

important to us as Jews who engage in prayer. Readers may be surprised to learn

that understanding the precise role of the hitpael

can be very important to those of other religions as well. A passage at Gen.

22:18 describes the relationship of the nations of the world with the seed of

Abraham:

again at Gen. 26:4.) Whether this phrase teaches that the nations of the world

will utter blessings using the name

of the seed of Abraham or be blessed

through the seed of Abraham depends on the precise meaning of the hitpael here. Much ink has been spilled

by Christian theologians on the meaning of hitpael

in this phrase.[20]

could be so interesting and profound!

mean “let us strengthen ourselves,” “let us continually be strengthened,” or

“let us be strengthened”? I will leave

it to you to decide!)

thank my son Rabbi Shaya First for reviewing and improving the draft.

commentary translated by Isaac Levy includes the following (at Gen. 20:7): התפלל means: To take the element of God’s truth,

make it penetrate all phases and conditions of our being and our life, and

thereby gain for ourselves the harmonious even tenor of our whole existence in

God…. [התפלל

is] working on our inner self to bring it on the heights of recognition of the

Truth and to resolutions for serving God…Prior to this, the commentary had pointed

out that the root פלל means “to judge” and that a judge brings

“justice and right, the Divine Truth of matters into the matter….”

Aryeh Leib Gordon explained that the word for prayer is in the hitpael form because prayer is an

activity of change on the part of the petitioner, as he gives his heart and

thoughts to his Creator; the petitioner’s raising himself to a higher level is

what causes God to answer him and better his situation. See the introduction to Siddur Otzar Ha-Tefillot (1914), vol. 1,

p. 20. The Encylcopaedia Judaica is

another notable source that uses the term “self-scrutiny” when it defines the

Biblical conception of prayer. See 13:978-79. It would be interesting to

research who first suggested the self-judge/self-scrutiny definition of prayer.

I have not done so. I will point out that in the early 13th century

Radak viewed God as the one doing the judging in the word התפלל. See his Sefer

Ha-Shorashim, root פלל.

and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (1994). The authors do cite the

article by E.A. Speiser (cited in the next note) that advocates the

interpretation. But they cite the article for other purposes only. The

interpretation of התפלל that Speiser

advocates and that I will be describing is nowhere mentioned.

“[o]utside Hebrew, the stem pll is at

best rare and ambiguous.” See his “The Stem PLL

in Hebrew,” Journal of Biblical

Literature 82 (1963), pp. 301-06, 301. He mentions a few references in

Akkadian that shed very little light. There is a verb in Akkadian, palālu, that has the meaning: “guard,

keep under surveillance.” See the פללarticle in Theological

Dictionary of the Old Testament, vol. 11, p. 568 (2001), and

Koehler-Baumgartner, entry פלל, p. 933. This perhaps

supports the “assess” and “think” meanings of the Hebrew פלל.

meaning at Is. 16:3 (asu pelilah) is

vague but could be “justice.” The meaning at Is. 28:7 (paku peliliah) (=they tottered in their peliliah) seems to be a legal decision made by a priest. Finally,

there is the well-known and very unclear ve-natan

be-flilim of Ex. 21:22. Onkelos translates this as ve-yiten al meimar dayanaya. But this does not seem to fit the

words. The Septuagint translates the two words as “according to estimate.” See

Speiser, p. 303. Speiser is unsure if this translation was based on guesswork

or an old tradition, but thinks it is essentially correct.

translated in this verse as “hope.” Even though this interpretation makes sense

in this verse, I am not aware of support for it in other verses. That is why I

prefer “think” and “assess,” which are closer to “intervene” and “judge.” Many

translate the word as “judge” in this verse: I did not judge (=have the

opinion) that I would see your face. See, e.g., The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon, entry פלל.

their entry פלל. Alternatively, some translate ויפלל here as “executed judgment.”

suggested that the “judge” meaning is just a later development from the

“intervene” meaning.

given varies from study to study. I have also seen references to 946, 780 and

“over 825.” See Joel S. Baden, “Hithpael and Niphal in Biblical Hebrew:

Semantic and Morphological Overlap,” Vetus

Testamentum 60 (2010), pp. 33-44, 35 n.7.

Most likely, the standard Hebrew hitpael

is a conflation of a variety of earlier t-stem forms that had different roles.

See Baden, p. 33, n. 1 and E.A. Speiser, “The Durative Hithpa‘el: A tan-Form,” Journal of the American Oriental Society

75 (2) (1955), pp. 118-121.

with regard to the hitpael of אבל, the implication may be “to be in mourning

over a period of time.” With regard to התמם

(the hitpael of תמם; I I Sam. 22:26 and Ps.18:26.), the implication may be “to be

continually upright.” Some more examples: משתאה at Gen. 24:21 (continually gaze), תתאוה

at Deut. 5:18 (tenth commandment; continually desire), ויתגעשו at Ps. 18:8 (continually

shake), and התעטף

at Ps. 142:4 (continually be weak/faint ). Another example is the root נחל. When it is in the hitpael, the implication may be “to come into and remain in

possession.”

pp. 249-250, and Speiser, The Stem PLL,

p. 305.

concession.” See his comm. to Deut. 3:23. This is farfetched. Hayim Tawil

observes that there is an Akkadian root enēnu,

“to plead,” and sees this Akkadian root as underlying the Hebrew התחנן. He views the hitpael as signifying that the pleading is continous (like the

import of the hitpael in hithalekh). See his An Akkadian Lexical Companion For Biblical Hebrew (2009), pp.

113-14. But there is insufficient reason to read an Akkadian root into התחנן, when we have a very appropriate Hebrew

root חנן.

Dictionary of the Old Testament, vol. 11, p. 568, Ernest Klein, A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of

the Hebrew Language for Readers of English (1987), p. 511,

Brown-Driver-Briggs, entry פלל, and

Koehler-Baumgartner, entry פלל, p. 933.

here remarks that this was “a form of worship common to several cults with the

purpose of exciting the pity of the gods, or to serve as a blood-bond between

the devotee and his god.”

vol. 11, p. 568, Klein, p. 511, and Koehler-Baumgartner, entry

פלל, p. 933.

to have located as many as 68 such instances in Tanakh, but does not list them. For the reference, see Baden, p.

35, n. 7. Baden doubts the number is this high and believes that the true

number is much lower. Baden would dispute some of the examples that I am

giving. Hitpaels with true passive

meanings are found more frequently in Rabbinic Hebrew. The expansion of the

meaning of the hitpael stem to

include the true passive form took place in other Semitic languages as well.

See O.T. Allis, “The Blessing of Abraham,” The

Princeton Theological Review (1927), pp. 263-298, 274-278.

others are collected at Allis, pp. 281-83.

For a few more true passives, see Kohelet 8:10, I Sam. 3:14, Lam. 4:1,

and I Chr. 5:17.

and Chee-Chiew Lee, “Once Again: The Niphal and the Hithpael of ברך in the Abrahamic Blessing for the

Nations,” Journal for the Study of the

Old Testament 36.3 (2012), pp. 279-296, and Benjamin J. Noonan, “Abraham,

Blessing, and the Nations: A Reexamination of the Niphal and Hitpael of ברך in the Patriarchal Narratives,” Hebrew Studies 51 (2010), pp. 73-93.

Torah Under Wraps

Torah Under Wraps

by Yoav Sorek

translated by Daniel Tabak

Their publications are not allowed to get out. Their roiling Internet forums are blocked by filters. The articles they publish omit the names of professors considered verboten. A cohort of Haredi scholars [1] challenge the academy and their natural surroundings, unafraid to deal with subjects deemed taboo in the yeshiva world. Few Religious Zionists have penetrated this alternative ivory tower, but one of them—Eitam Henkin, may his blood be avenged—succeeded in breaking down barriers.

*