Rabbi Chaim Volozhin’s Motivation to Write Nefesh HaChaim

Rabbi Chaim Volozhin’s Motivation to Write Nefesh HaChaim

(Including a response to R. Bezalel Naor’s Review of Nefesh HaTzimtzum)

Avinoam Fraenkel

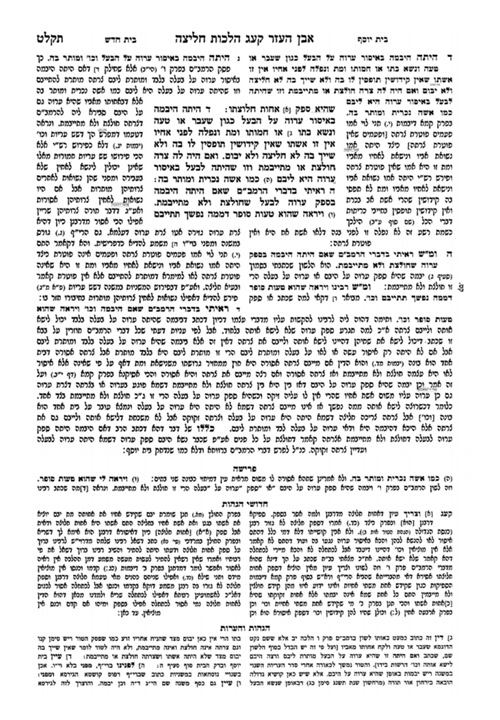

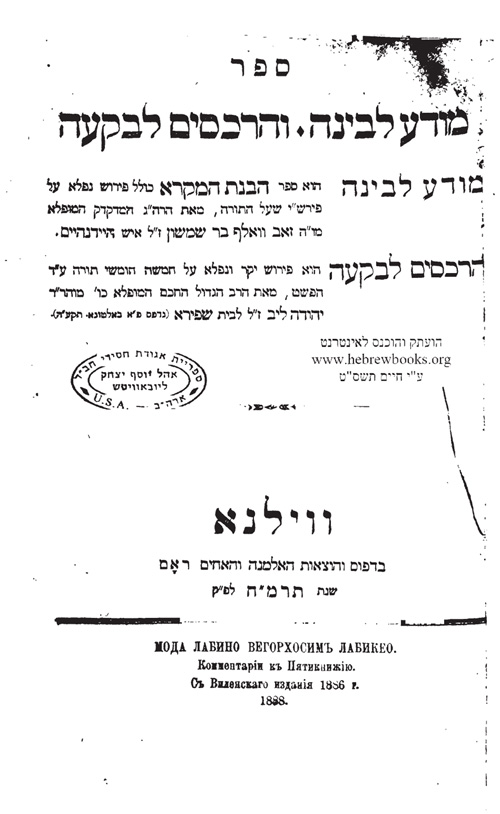

Avinoam Fraenkel’s new 2 volume work, Nefesh HaTzimtzum (Urim Publications), is a full facing page translation and extensive commentary on Nefesh HaChaim together with all related writings by R. Chaim Volozhin. It also presents a groundbreaking study on the Kabbalistic concept of Tzimtzum which is demonstrated to be the key principle underpinning all of Nefesh HaChaim. The following essay captures some of the key insights in overview from Nefesh HaTzimtzum which should be referred to for in-depth details and sources.[1]

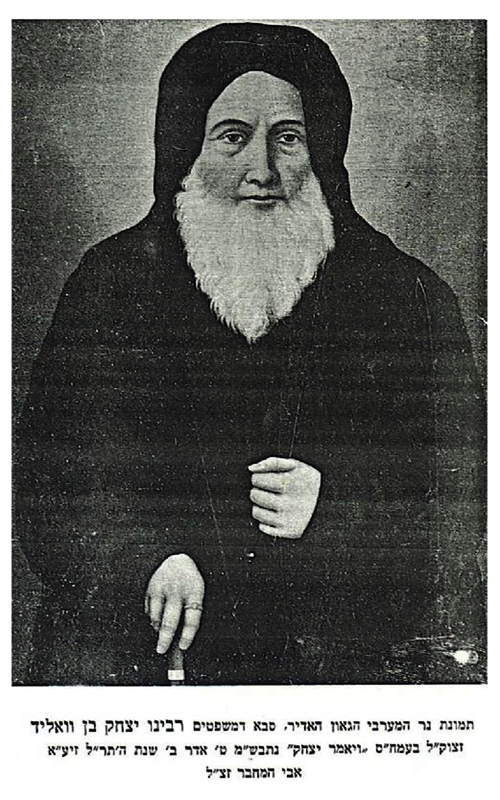

Life is complex and our most significant actions in life are often motivated by a wide spectrum of catalysts driven by both conscious and subconscious objectives. Therefore it is a considerable challenge when looking deeply into R. Chaim Volozhin’s magnum opus, Nefesh HaChaim, to try to ascertain what may have primarily driven him to compose it and what motivated him to provide an urgent deathbed instruction to his son in 1821, to publish it as soon as possible.[2]

Was it simply a structured presentation, recording the enormously important worldview of R. Chaim’s revered master, the Vilna Gaon? Was it a manifesto to set the tone for his newfound and soon to be world famous Volozhin Yeshiva? Was it a broadside shot at the entire Chassidic establishment to attempt to bring it into line? Was it a defense for the Mitnagdic camp, to shore up their opposition to the Chassidim by providing them with its own authoritative framework to dampen any attraction to the looming specter of what for many was the compelling allure of the competing Chassidic philosophy?

In all likelihood, all of these factors and many more, both communal and personal, may have motivated R. Chaim, at least to some degree. Nevertheless, on investigation, it appears that there was indeed a single primary motivating factor that can be isolated as significantly influencing the presentation of Nefesh HaChaim. However, in order to be able to relate to this factor, it is necessary to first dispel a smokescreen of deep rooted misconception which has persisted for the last 200 years about perceived fundamental differences of faith between the Chassidim and the Mitnagdim. Once dispelled, as explained below, it becomes clear that R. Chaim aimed his urgent message in Nefesh HaChaim at many on the periphery of the Chassidic movement, but not directly at the Chassidic establishment itself. He perceived those on the periphery to be at severe risk of compromising their faith due to their mistaken adoption of practices whose sole objective was to passionately increase their piety to get closer to God at all costs even if this would ironically result in Halachic compromise.

This smokescreen was a result of raging turmoil between the Chassidim and their opponents, the extent of which was so acute that it caused many to be utterly confused as to what the fight was actually about. It prepared the ground for it to be all too easy to believe and accept that the schism was about the fundamental principles of Judaism focusing, in particular, on the Kabbalistic concept of Tzimtzum and the degree to which God is directly manifest in this physical world – and therefore to have a different perception of the required balance between the desire to get closer to God and the necessary punctilious observance of the Halacha. So, even though many equivalences can be found between statements in Nefesh HaChaim, the contemporary Chassidic literature of its time in general and Sefer HaTanya in particular, the profound importance of the key message of Nefesh HaChaim to the wider Chassidic community was entirely misunderstood and therefore totally ignored, as Nefesh HaChaim was perceived to have been based on a fundamentally different philosophical outlook that diverged from what was mistakenly thought by many to be the exclusively Chassidic view on the extent of God’s immanence.

It should be noted that this is not just of historic interest in that it was only relevant in R. Chaim’s day. Even though the acuteness of the schism between the Chassidim and Mitnagdim has abated and both camps, although with some exceptions, are generally accepting of each other nowadays, nevertheless the prevalence of Halachic practice becoming the primary casualty of a desire to get closer to God is in many ways just as rife today as it ever was. This impacts all camps across the entire spectrum of Jewish religious affiliation. The less religiously affiliated who are susceptible to possibly view Halachic compromise as sometimes being acceptable if they see it as enabling more of their activities to otherwise be closer to God. The more religiously affiliated who frequently adopt pious self-imposed practices going beyond the letter of Halachic obligation, where out of what they call “Frumkeit,” are vulnerable to possibly look down on, speak about and act disdainfully with baseless hatred towards others who they may view as less pious, flagrantly and often publicly breaching the Halacha. This phenomenon is arguably manifest in its worst form in instances of acts of open aggression in the name of God against Jews by some extremist Jews who try to enforce what they perceive to be a high level of piety, where neither the aggression nor the supposed piety conform with anything even vaguely close to any accepted standard of Halachic practice. R. Chaim’s message is therefore just as urgently required and relevant today and the fact that Nefesh HaChaim has largely been ignored for the last 200 years has prevented its critical message from being properly communicated and absorbed.

It should also be highlighted that while the Chassidic community has ignored the message of Nefesh HaChaim due to their perception of the entire work as being philosophically disconnected from their own outlook, the Mitnagdim on the other hand have had a problem accepting the widespread study of Kabbalah. No-one in the Mitnagdic community has any authority or would dare to challenge the status of Nefesh HaChaim as a seminal work that must be studied. Nevertheless, many in the Mitnagdic community have been generally guilty of attempting to rebrand Nefesh HaChaim, trying to ignore that it is a Kabbalistic work, failing to appreciate, or even denying outright, that engagement in the Kabbalistic concepts it so intentionally presents for public consumption is an absolute pre-requisite to properly relate to its message. They surreptitiously treat it as an ethical work, a work of Mussar, by only focusing study on some selected non-Kabbalistic parts of the book and thereby entirely miss the point of the book.[3]]Therefore from either the Chassidic or Mitnagdic perspective, the key burning message of Nefesh HaChaim which so badly needs to be applied to Jewish life today, has sadly and irresponsibly been ignored!

The historic smokescreen of fundamental difference between the Chassidic and Mitnagdic camps has unfortunately been propagated by many of great stature in the Jewish world and also by many in the academic world. Simply put, the general mistaken presentation of difference around the Tzimtzum process which explains why we cannot see the infinite God in this finite physical world, is that the Chassidic view is that God is present everywhere and in everything physical but His presence is concealed, i.e., God is totally immanent. Whereas the Mitnagdic view is that God is removed and absent from the physical world and merely controls all from a distance through Divine Providence, i.e., God is totally transcendent.

This unfortunate presentation was perhaps most famously captured by a letter written in 1939 by R. Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the last Lubavitcher Rebbe, which delineates a 4 position approach to the concept of Tzimtzum and presents a picture of stark contrast between each of the views of the Vilna Gaon, the Baal HaTanya and R. Chaim.[4] In this letter R. Schneerson went so far as to state “… the author of Nefesh HaChaim … disagrees with his master, the Vilna Gaon [about the concept of Tzimtzum]. In general, it appears that R. Chaim Volozhin saw the works of Lubavitch – and Sefer HaTanya, in particular – and that he was influenced by them, however, I do not have definite proof of this.” In contrast to the positions of both the Vilna Gaon and R. Chaim, R. Schneerson then continued to explain the Chassidic view, that the Tzimtzum process was only initially applied to “the lowest level of the Light [of the Ein Sof].”

R. Schneerson’s statement here explicitly highlights a diverse difference in fundamental philosophical outlook between the Chassidic world and that of the Vilna Gaon and therefore the Mitnagdic world. His suggestion, without proof, that R. Chaim was swayed somewhat towards what he describes as the Chassidic view was based on the employment of many seemingly Chassidic statements in Nefesh HaChaim.

However, on in-depth study of the positions of the Vilna Gaon, R. Chaim and the Leshem[5] it becomes crystal clear that they are identical with the Baal HaTanya, and indeed with the Arizal and the Zohar, regarding the concept of Tzimtzum. In order to see this it is crucial not to initially look at the terminology they employ but to carefully assess the substance of each of their arguments. On face value, the Vilna Gaon and the Leshem seemed to openly express strong dissatisfaction with the Chassidic perspective and there is scope to question if the Baal HaTanya aimed scathing comments on this topic directly at the Vilna Gaon. Notwithstanding this, if we are particular to examine what they actually say about the substance of the topic, and not be deflected about what they may or may not have said about each other, then it will allow us to see that they in fact all agreed.

The critical factor to appreciate the substance of each of their arguments is to understand that they all saw the arena within which the Tzimtzum process occurs as only being in the Sefira of Malchut of any level, including that of the highest level called the “Ein Sof.”[6] Malchut is the lowest Sefira of any level and is in fact in a different dimension to it. This means that any change within Malchut of any level as a result of the Tzimtzum process, does not impact the level itself in any way. Therefore, the first instance of the Tzimtzum process which occurred in the Malchut of the first level which was emanated from God’s Essence, the Ein Sof, did not impact the Ein Sof in any way. Therefore, by extension, not only does the Tzimtzum process not change the Ein Sof, it also has no impact on God’s Essence in any way.

Once this is understood then it becomes clear that the debate over whether Tzimtzum means either immanence or transcendence is simply wrong. As the Tzimtzum removal only occurs within Malchut, transcendence only applies to Malchut. Therefore, everything above Malchut, i.e., both God’s Essence and also the Ein Sof, is entirely and absolutely immanent. In other words, the Tzimtzum process itself results in a dual simultaneous combination of both immanence and transcendence. The particular stance of immanence or transcendence then becomes a matter of perspective. In the language of the Nefesh HaChaim, immanence is “Mitzido”, the perspective of the higher level (and ultimately God’s perspective) and transcendence is “Mitzideinu”, the perspective of the lower level (and ultimately that of the physical creations).[7] All discussion about the differences between levels therefore becomes relative to the level the discussion is centered upon. This point is so important that it is the key to begin to understand any discussions of the Arizal.[8]

This, in a nutshell, is the concept of Tzimtzum that was held in common by the Vilna Gaon, R. Chaim, the Leshem, the Arizal and the Zohar. Any time any one of these sources refers to a “removal”, they are therefore referring to a removal within “Malchut” only of whatever level they happen to be discussing. It is far beyond the scope of this essay to provide sources to explain the concepts and demonstrate how they translate into day to day life and the reader is referred to Nefesh HaTzimtzum.[9]

However, just to whet the appetite and demonstrate that our focus must be on the substance of the argument and to not be deflected by terminology let’s look at two simple sources. The Baal HaTanya states “… the characteristic of His Malchut is the characteristic of Tzimtzum and concealment, that conceals the light of the Ein Sof.”[10] This, unsurprisingly, is consistent with R. Schneerson’s statement that the Tzimtzum process was only initially applied to “the lowest level of the Light [of the Ein Sof].” The Leshem, on the other hand, states the following “…and therefore that place within which the Tzimtzum process occurred is called Malchut of the Ein Sof … it is exclusively in Malchut of every revelation for every Tzimtzum is exclusively in Malchut ….”[11] Therefore, very surprisingly to many, the Leshem, the staunch Mitnaged and follower of the path of the Vilna Gaon, entirely agrees with the Baal HaTanya and with what R. Schneerson presents as the Chassidic view that the Tzimtzum process is only within Malchut!

With all of the above in mind, we are now in a position to step aside and briefly focus our attention on R. Bezalel Naor’s review of Nefesh HaTzimtzum (see here). In his eloquent review, he “cuts to the chase,” as he puts it, to describe his argument against the Tzimtzum thesis of Nefesh HaTzimtzum. Unfortunately, he “cuts” out more than he “chases” and it is astonishing that in his entire review, R. Naor doesn’t even vaguely mention or make any attempt to counter the key critical factor presented above that is emphasized numerous times in Nefesh Hatzimtzum, that all the players in the Tzimtzum discussion agree with each other that Tzimtzum happens exclusively in Malchut! It seems that R. Naor, in common with many of great stature before him, has unfortunately fallen into the classic historical trap which has plagued this topic for centuries of focusing on a presumed understanding of the terminology employed by the various proponents, especially in their expressions of disagreement with their colleagues. In doing so he has failed to investigate the actual substance of their Tzimtzum argumentation and is unaware that they actually agreed with each other! (This response continues in the note.[12])

Stepping back to the main thread of this essay, historically most were severely misled and confused by a smokescreen of difference which was contributed to by two key factors. Firstly, by terminology used by some key Kabbalists, the historic context of which was misunderstood.[13] Secondly, by a famous letter forged in the name of the Baal HaTanya which explained the Vilna Gaon’s position on Tzimtzum as arguing with the view of Chassidut.[14] However, not all were misled. Rabbi Eliyahu Dessler, among many other prominent individuals, understood that the argument between the Chassidim and the Mitnagdim was not about the fundamental principles of Judaism. He wrote on the topic of Tzimtzum in 1938 that “in this generation in which there is a need to unite…it is fitting to publicize the fact that there are no differences of opinion in the essence of these issues”.[15]

After fully absorbing the fact that the philosophical outlook in relation to the Tzimtzum concept of the Vilna Gaon, R. Chaim, the Baal HaTanya and the Chassidic world are identical, the genius of R. Chaim’s presentation in Nefesh HaChaim can then be clearly seen. The Chassidic works of his day, including Sefer HaTanya, barely quoted their sources. In contrast, when R. Chaim presents his ideas in general, and the concept of Tzimtzum in particular, ideas which at the time were seen by many to be uniquely Chassidic ideas, he frames them in the context of extensive quotations from and references to traditional Jewish sources. As mentioned above, he even uses many similar expressions and sentences to those appearing in the Chassidic works of his day. He is demonstrating that there is no scope for anyone to suggest that there is a fundamental difference between the formal outlook of the Chassidic Movement and that of mainstream Judaism and that the paths for serving God of both the Chassidim and the Mitnagdim are fundamentally the same and are derived from the same Torah and the same Mesorah. Therefore, against a historic backdrop of some who erroneously thought that the new Chassidic Movement had blazed a new trail in Judaism and were using the inspiring Chassidic presentation of these concepts to compromise Halacha, R. Chaim’s key message is, there is no basis for anyone to bend these concepts out of their true context of mainstream Judaism, and as a result, there is no basis to use them to license Halachic compromise in any way whatsoever.

It is fascinating to note that R. Chaim was not alone in this quest to highlight the potential pitfalls of Halachic compromise resulting from an attempt to get closer to God. He was joined by some of the establishment Chassidic figures who expressed themselves in a very similar way.[16] Furthermore it is inconceivable that the Baal HaTanya would have sanctioned any form of Halachic compromise, as he is after all the author of the widely respected and accepted Halachic work, the Shulchan Aruch HaRav.[17]

The underlying principle guiding R. Chaim’s presentation in Nefesh HaChaim reflects the position of his master, the Vilna Gaon, that as the Kabbalah is an intrinsic part of the Torah, it cannot be that anything derived from it can prescribe any action which contradicts and is inconsistent with the Torah.[18] Any directive derived from the Kabbalah which contravenes the Torah and Halachic practice must therefore be a misunderstanding of Kabbalah. In addition, this principle was explicitly highlighted by some of the Chassidic masters who were also clearly objecting to the same phenomenon of Halachic compromise on the periphery of the Chassidic world that R. Chaim was objecting to.[19]

The outcome of all the above is that because of R. Chaim’s historic motivation to write Nefesh HaChaim, he has left us with a remarkable work, a motivational framework of how a person is to view and philosophically interact with the world, which substantiates every statement it makes by referencing many traditional Jewish sources in general, and Kabbalistic sources in particular. As a result, the highly structured presentation of Nefesh HaChaim itself is a unique gateway into the highly unstructured world of Kabbalah. It is a tremendous portal through which a genuine introduction to the world of Kabbalah and to the deeper meaning of the Torah has been made accessible to one and all. May the study of Nefesh HaChaim and R. Chaim’s Torah bring a true conscious awareness of unity in the Jewish World.

[1] Nefesh HaTzimtzum includes the following:

- A historical and structural introductory overview.

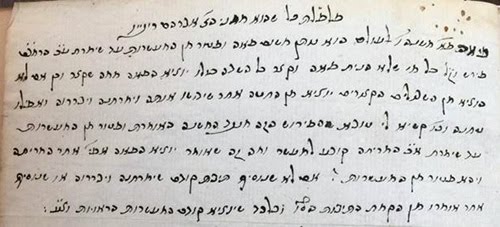

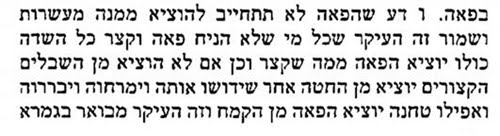

- A corrected Hebrew text for Nefesh HaChaim, likely to be the most accurate ever published.

- An innovative hierarchical presentation of both the Hebrew and facing page English texts for ease of use.

- Extensive explanatory annotations on all texts.

- Expansion in English translation of virtually all sources quoted and referenced in Nefesh HaChaim, including all Kabbalistic sources.

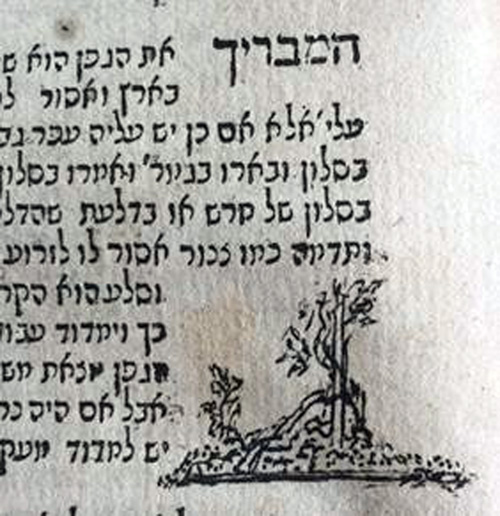

- An explanation of the concept of Tzimtzum with:

- Full details of the positions of the Zohar, the Arizal, Yosef ben Immanuel Irgess, R. Immanuel Chai Ricchi, the Vilna Gaon, the Baal HaTanya, R. Chaim Volozhin, the Leshem, R. Dessler and the Lubavitcher Rebbe, among others.

- Extensive source material in both the original Hebrew and facing page translation.

- A comparison between Nefesh HaChaim and Sefer HaTanya on their key approaches to Torah study, Mitzvah performance and prayer which are all based on their common understanding of the Tzimtzum concept.

- A demonstration of how the correct understanding of the Tzimtzum concept underpins the concept of Partzuf and therefore all of the Arizal’s Kabbalistic teachings.

- A presentation of the Vilna Gaon’s messianic outlook which is dependent on knowing Kabbalah and Science.

- An explanation of the concept of The World of the Malbush.

- Facing page translation of all of R. Chaim Volozhin’s published writings related to Nefesh HaChaim, including his single published sermon, letters and his introductions to commentaries of the Vilna Gaon on Shulchan Aruch, Zohar and Sifra DeTzniyuta (which includes the largest authentic published repository of stories of the Vilna Gaon by any of his students).

- Translated and cross-referenced extracts of all Nefesh HaChaim related sections from Ruach Chaim.

- Yosef Zundel of Salant’s brief extract on prayer with translation.

- Detailed outlines and extensive indexes by themes, people’s names and book references.

[2] As recorded by R. Chaim’s son, R. Yitzchak, in his introduction to Nefesh HaChaim. Nefesh HaChaim was subsequently published in 1824.

[3] Most of the Yeshivot which include the study of Nefesh HaChaim as part of their curriculum only study the last section, the Fourth Gateway. Most of the commentaries and translations that have been published to date omit comment on or even translation of the Kabbalistic material which forms a substantial part of the book.

[4] Iggrot Kodesh, published by Kehot, Volume 1, Letter 11.

[5] For a scholarly portrait of the Leshem which brings together much important biographical information, a succinct overview of the Leshem’s major works and many further sources, see Joey Rosenfeld, “A Tribute to Rav Shlomo Elyashiv, Author of Leshem Shevo v-Achloma: On his Ninetieth Yahrzeit,” the Seforim blog, 10 March 2015, available here.

[6] It is not in the scope of the discussion here to discuss what is meant by a Sefira or a level. In Kabbalistic terminology a level may be called a “World” or a “Partzuf”. A “Sefira” is a subcomponent of the “World” or the “Partzuf”.

[7] “Mitzido”/”Mitzideinu” are also synonymous with the Zohar’s terminology “Yichuda Ilaah”/ “Yichuda Tataah,” e.g., as per end of Nefesh HaChaim 3:6 (Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 1, pp. 510-511). Incidentally “Mitzido”/”Mitzideinu” are also synonymous with the terms of “Orot”/”Keilim”.

“Mitzideinu”, “Yichuda Tataah” and “Keilim” are all different expressions which mean “Malchut”.

[8] In particular, it is the dual simultaneous perspective which generates the concept of “Partzuf” which underpins all the discussions of the Arizal. See Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, pp. 145-150.

[9] In particular, to the first 2 sections of Volume 2.

… שמדת מלכותו היא מדת הצמצום וההסתר להסתיר אור אין סוף …

[11] Sefer Hakdamot UShearim, Shaar 7, Perek 5, Ot 1:

… ולכן נקרא אותו המקום שנתצמצם בו בשם מלכות דאין סוף … הנה הוא הכל בהמלכות של כל גילוי כי כל צמצום הוא רק בהמלכות …

There are many similar statements across the writings of the Leshem. This source is particularly explicit and the review of all of Ot 1 will be insightful.

[12] In continuation of the response to R. Naor’s review, a number of points have been picked up on as detailed below. Please note that all of these points are side issues and pale into insignificance compared to the details of R. Naor’s stark omission of the concept of Tzimtzum in Malchut as per the main essay text. These points are as follows:

(1) In note 1 of his review, R. Naor quotes Dr. Menachem Kallus and mentions that in a note to Etz Chaim, R. Meir “Poppers writes that it sounds to him as if Luria’s disciples Rabbi Hayyim Vital and Rabbi Yosef ibn Tabul understood from the Rav [Isaac Luria] that ‘the Tzimtzum is literal’ (‘ha-tzimtzum ke-mishma‘o’).”

R. Naor’s suggestion here is that the Arizal is saying that the Tzimtzum process results in total literal removal and transcendence of God from physicality. However, in the light of the fact that we now know that the Tzimtzum process that the Arizal is referring to only took place in Malchut of the Ein Sof, this point is simply not relevant as the removal and transcendence only occurs in Malchut, from the perspective of the creations, Mitzideinu, but at the same time there is a total immanence of God within the unchanged presence of the Ein Sof.

Even the Baal HaTanya agrees that there is a removal in Malchut, resulting in physicality from our perspective, as he says e.g., in Sefer HaTanya 2:3 that our “flesh eyes” only see physicality.

Also see the particularly explicit statement of the Baal HaTanya in Sefer HaTanya 4:20 which is a direct corollary of the Mitzido/Mitzideinu concept of Nefesh HaChaim: “Relative to [God – i.e., Mitzido], the created physical entity is as if it has no consequence, i.e., its existence is nullified relative to the power and the light which is bestowed within it. It is like the radiance of the sun [before it has emanated and is still] within the sun. This is specifically relative to Him, where His Awareness is from above to below. However, from the perspective of the awareness of [the created entities – i.e, Mitzideinu,] from below to above, the created physical entity is an entirely separate/disconnected entity, with this awareness and perception being [only] from below, as [from its perspective] the power which is bestowed within it is absolutely not perceived at all.”

Multiple sources from across Sefer HaTanya directly expressing the Mitzido/Mitzideinu concept are brought in Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, pp. 94-95, fn. 120.

(2) R. Naor quotes from R. Yitzchak Aizik of Homil, one of the greatest students of the Baal HaTanya who stated that the Mitnagdim “have no room for this faith that All is God.”

It is of interest to note that R. Dessler was a close student of R. Mordechai Duchman who in turn was a close student of R. Yitzchak Aizik of Homil (See Nefesh Hatzimtzum, Vol. 2, p. 305, fn. 474). R. Dessler was therefore intimately familiar with the works of Lubavitch and would have most certainly been aware of R. Yitzchak Aizik of Homil’s comment. Notwithstanding this he clearly saw that Tzimtzum was not the issue of the Machloket and valiantly tried to publicize this, as quoted in the continuation of this essay.

(3) The Baal HaTanya’s rejection of “Tzimtzum Kipshuto” (Sefer HaTanya 2:7) uses scathing, derisive language to describe those who hold by that position referring to them as “scholars in their own eyes” (Yishayahu 5:21) and that “they also do not speak intelligently” (Iyov 34:35). The question is who was the Baal HaTanya referring to? Nefesh HaTzimtzum presents a number of arguments to say that it could not have been the Vilna Gaon or R. Ricchi and by a process of elimination would then be referring to the Shabbatians. R. Naor rejects this position but in doing so starkly omits most of the argumentation from Nefesh HaTzimtzum!

A brief summary of the main Nefesh HaTzimtzum arguments is presented as follows (see Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, pp. 75-79 for much more detail on this).

Firstly and most importantly, even if we were to say that the Baal HaTanya was directing his statements at the Vilna Gaon and disagreed with what he may have assumed was the Vilna Gaon’s position, it doesn’t change the fact that the Vilna Gaon actually agreed with the Baal HaTanya on Tzimtzum only occurring in Malchut. So the debate about who the Baal HaTanya was referring to, while it may be interesting, is academic as far as who held what about Tzimtzum is concerned, as both the Baal HaTanya and the Vilna Gaon shared a common position.

R. Naor severely underplays the level of vitriol in the Baal HaTanya’s tone and considers that his statements are mild. In Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, p. 75, fn. 80, a number of sources are brought which demonstrate that Chazal very specifically used both the expressions “scholars in their own eyes” and “they do not speak intelligently” to refer to the “wicked”, e.g., “. . . and even among the wicked there are scholars, as it says . . . ‘Woe to those who are scholars in their own eyes’” (Bereishit Rabbati, Toldot, on Bereishit 26:12). Even if one could make a (somewhat forced) argument that the Baal HaTanya is taking these expressions out of their original context, since the Baal HaTanya quotes directly from R. Ricchi’s Mishnat Chassidim twice in Sefer HaTanya, it is highly questionable to suggest that such a punctilious author would quote holy statements from anyone he directly refers to derisively as “a scholar in his own eyes” and implies that he is wicked!

The section of Sefer HaTanya which included these statements, although distributed to the Baal HaTanya’s students and is extant in manuscripts of Sefer HaTanya, was only inserted for the first time in a published edition of Sefer HaTanya in the 1900 Romm edition some 88 years after the passing of the Baal HaTanya. It should be noted that this section was not just a few lines containing caustic statements. It actually ran on for a number of pages. The majority of the information it contains is repeated from other places in Sefer HaTanya, although brought together in an effective presentation in one place. Even though this is the only place in Sefer HaTanya that the specific expression “Tzimtzum Kipshuto” is used, the rejection of this position is very clear from the presentation of Tzimtzum in other places in Sefer HaTanya. Therefore, if it were just 2 or 3 caustic statements that were not initially included in Sefer HaTanya and were later inserted in the 1900 edition, it could reasonably be argued (as R. Naor suggests) that they were not included due to the raging arguments at the time of the original printing in 1796 and that they therefore were pointed at the Vilna Gaon. However, if the Baal HaTanya wanted to include this section, it would have been trivial for him to simply edit the 2 or 3 very brief caustic statements to make them politically correct. The fact that he did not edit these statements, but omitted the entire lengthy section, suggests that there was another reason for the omission.

It should also be noted that the Vilna Gaon, never used the expression “Tzimtzum Kipshuto” in any of his writings and also, as already explained, did not actually hold this position. This means that if the Baal HaTanya was directing his vitriol at the Vilna Gaon, he was doing so based on rumor. On the Baal HaTanya’s release from prison in 1798, he wrote a letter outlining the importance of remaining silent in the face of controversy, strongly highlighting that this is a characteristic of those close to God (Sefer HaTanya 4:2). Given the devotional premium that he attached to remaining silent in the face of controversy it would have been complete hypocrisy were the Baal HaTanya to have been openly derisive about his main partner in controversy. This is accentuated by the fact that the Vilna Gaon did not actually hold this position and the Baal HaTanya’s attack would have been based on rumor.

(4) R. Naor quotes what he refers to as a key passage from Yosher Levav (Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, pp. 260-261): “Therefore relative to us (le-gabei didan), it is as if there was no Tzimtzum and we can say that the Tzimtzum is not literal. However, relative to the Ein Sof (le-gabei ha-Ein Sof) itself, it is literal.” He argues that as R. Ricchi is saying that relative to the creations the Tzimtzum is not literal, how can Nefesh HaTzimtzum present R. Ricchi as saying that relative to the creations the Tzimtzum IS literal?

Unfortunately, R. Naor omits to present the very specific and complex context of R. Ricchi’s statement which appears in Yosher Levav, Ch. 15 – and as a result his statement is misleading!

The context is set at the beginning of Ch. 15, arguably the most subtle argument in the Yosher Levav’s overall Tzimtzum presentation, saying “Even though we have proven that the Tzimtzum process itself is literal, nevertheless there is scope to say that the way in which the Tzimtzum process was applied was not literal”.

R. Ricchi spent the previous few chapters explaining that the Tzimtzum process is literal and earlier (Yosher Levav, Ch. 13) he makes a key statement: “even though I cannot imagine how this could be [literal], as I have no knowledge of how He can contract Himself since there was no space empty of Him – this is my deficiency, as I have no way of knowing anything about His Exalted Unity.” He is saying that God’s perspective is unknowable and notwithstanding God’s point of view of there being no space empty of Him, that from the point of view of the creations there is an apparent literal removal of God even though, as R. Ricchi highlig hts, he cannot logically relate to how this can be so. Therefore R. Ricchi’s general position is that from our point of view, relative to us, Tzimtzum IS literal.

In contrast, the very specific context of the beginning of Yosher Levav, Ch. 15, is discussing a scenario after the literal Tzimtzum has already taken place. R. Ricchi explains that after the literal Tzimtzum, there still remained a residue, called a “Reshimu,” which has greater creative intensity than anything we could ever imagine – therefore relative to us, we cannot differentiate between the intensity of the Reshimu and of the Ein Sof, so we would relate to the Reshimu in the same way as we do to the Ein Sof and therefore relative to us there is scope to say that it is as if there was no Tzimtzum – however relative to the Ein Sof it is literal, because compared to the Ein Sof the Reshimu is like something physical.

This point is succinctly related to in Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, p. 70, fn. 65.

[13] In particular by R. Yosef ben Immanuel Ergas and R. Immanuel Chai Ricchi. See Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, pp. 63-71, for details.

[14] This forged letter is published in Iggrot Kodesh Admor HaZaken, published by Kehot in 1987, letter 34, p. 85. It was first published as an appendix to Metzaref HaAvodah, 1858 – which was also an entirely forged work. For extensive details and hard evidence of both the letter and Metzaref HaAvodah forgeries, see Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, pp. 79-88.

[15] This was from a letter written by R. Dessler expressing his position on Tzimtzum. It was R. Dessler’s position which prompted the response by R. Schneerson in his 1939 letter. R. Dessler’s complete letter is published in Kodshei Yehoshua by his son in-law R. Eliyahu Yehoshua Geldzahler, Volume 5, Siman 421, pp. 1716–1717. It is also partially printed in Michtav MeEliyahu by R. Eliyahu Dessler, Volume 4, p. 324. This part of the letter only appeared in earlier print editions of Michtav MeEliyahu and was removed from the more recent print editions when its editor later decided to include another paragraph which was previously omitted (the complete letter could not be included at that stage as the book layout had been fixed and the contents of this letter had to be restricted to a single page).

[16] E.g., R. Tzvi Elimelech Shapira of Dinov, the Bnei Yisaschar, in Derech Pikudecha, Mitzvah Lo Taaseh 16, Chelek Hamachshava 4. Also R. Nachman of Breslov in Sichot Moharan, Siman 267. See Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, pp. 137-138, fn. 217.

[17] E.g., as quoted frequently by the Chafetz Chaim in his Mishneh Berurah, referring to the Baal HaTanya as “HaGraz”, “HaGaon Rabbi Zalman.”

[18] See R. Chaim’s introduction to the Vilna Gaon’s commentary on Zohar as brought in Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, p. 464.

[19] E.g., R. Tzvi Hirsch of Zidichov in Sur MeRah VeAseh Tov, pp. 79–80 of the Emet publication,

Jerusalem, 1996. Also R. Yitzchak Issac Yehuda Yechiel of Komarna in Zohar Chai, Hakdamat Sefer HaZohar, p. 41b. See Nefesh HaTzimtzum, Vol. 2, pp. 138-139, fn. 217.