Some Recollections of R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, Love Before Marriage, and More

הרב ויינברג: דער אלטער ז”ל (דער סלאבאדקער, זאגט מען דער אלטער), ר’ נטע הירש, ער איז דאך א צדיק.

הרצוג: אבער נישט קיין למדן.

הרב ויינברג: נישט קיין גרויסער למדן. ער האט געקענט לערנען, אבער ער איז נישט געווין קיין גרויסער למדן. אבער ער איז געווען א חכם, א גרויסער.

הרצוג: יא, דער חכם פון סלאבאדקע.

הרב ויינברג: און ער איז געווען א איידעלער מענטש זייער.

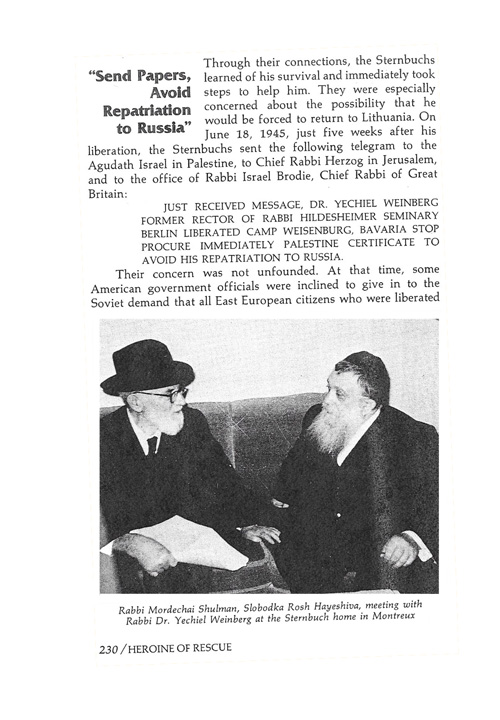

ויינברג: ער איז ארויפגעקומען צו מיר אין סעמינאר. ער איז געווען אין בערלין, זיך ארומגעדרייט צוויי מאנאטן. געוואלט אריין אין סעמינאר. האב איך אים געזאגט: הערט זיך איין, ר’ מרדכי, ער איז א טיקטינר. דו וועסט נישט ווערן קיינמאל קיין דאקטאר. און אויב דו וועסט זיין א דאקטאר אפילו, וועסטו קיינמאל נישט קריגן קיין רבינער שטעלע אין דייטשלאנד. וואס טויג עס דיר? וועסט נישט מאכן קיין קאריערע. איז גיי אוועק צוריק אין סלאבאדקע. אמאל קען זיין, דו וועס זיך פארליבן אדער זי וועט זיך אין דיר פארליבן, די טאכטער פון ר’ אייזיק’ן, וועסטו ווערן ר’ אייזיק’ס א איידים.

.הרצוג: וכך הווה

.ויינברג: און איך האב אים דערמאנט דאס. אז איך האב עס אים אמאל פאראויס געזאגט

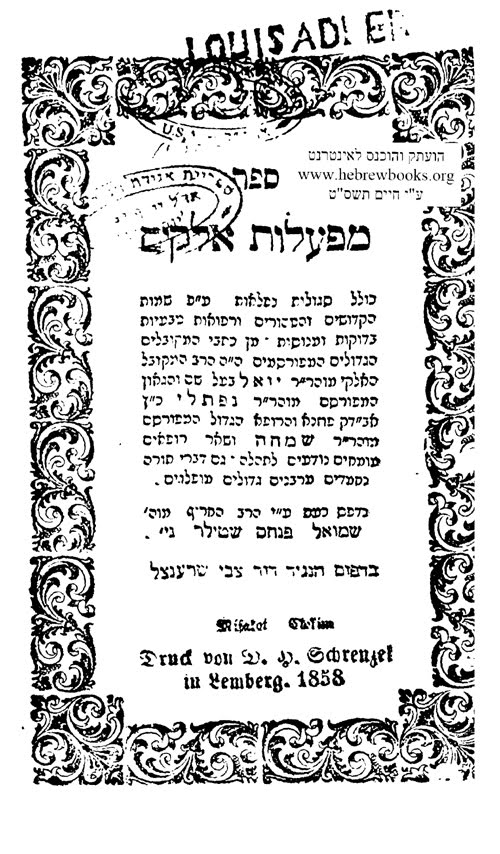

Also of interest is this picture that appears at the beginning of each section of the book. As I learnt from Shimon Steinmetz, urinating putti were a common theme in the art of Archivolti’s day. You can read about it here.

[1] Israel State Archives, Yaakov Herzog Collection, 2989-4/פ. R. Yaakov David Herzog was the son of R. Isaac Herzog. He was named after R. Yaakov David Wilovsky, the Ridbaz, from whom R. Isaac Herzog received semikhah. In addition to his public role in government and as a diplomat, Yaakov Herzog was also a rabbinic scholar. In 1945 he published a translation and commentary of Mishnah Berakhot, Peah, and Demai. This translation was actually ready for publication by the end of 1942, before Herzog was even 21 years old (he was born Dec. 11, 1921). See Michael Bar-Zohar, Yaacov Herzog: A Biography (London, 2005), p. 50.

[2] Shlomo Tikochinski, Lamdanut, Musar ve-Elitizm (Jerusalem, 2016) p. 111 n. 131, cites Israel Zissel Dvortz and Dov Katz who claim that R. Finkel was indeed a “gadol” in talmudic learning, but he hid this knowledge even from those who were close to him. Some will no doubt regard this judgment as motivated by “religious correctness,” especially as R. Weinberg had a particularly close relationship with R. Finkel and was privy to all sorts of private information. See, however, Nathan Kamenetsky, Making of a Godol, pp. 777ff., who cites additional sources testifying to R. Finkel’s talmudic knowledge.