The Agunah Problem, part 2; Wearing a Kippah; More Censorship by ArtScroll

הכל יודעים ששום בת ישראל לא תנשא לאיש שהמיר דתו אפילו אם עשה אח”כ תשובה בלבו ואפילו אם ימיר את דתו החדשה בדת ישראל.

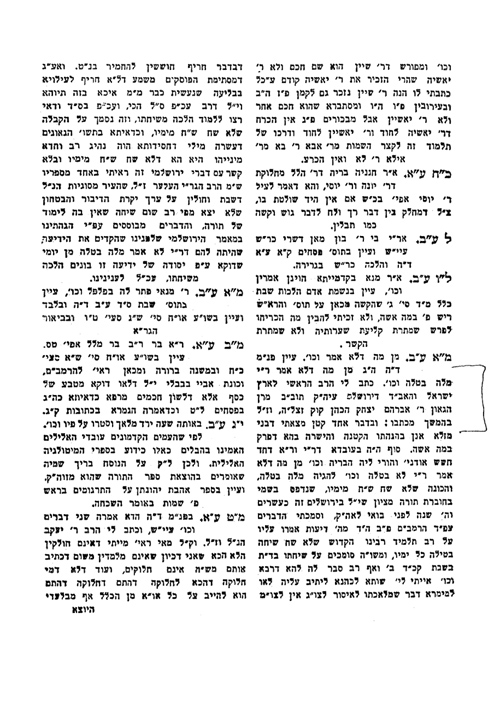

ואחרי זאת בקחתנו גם בחשבון חומר השעה המיוחד שאנו חיים בה בתקופתנו אשר רבו שוטני התורה וכן בראותינו פירצת הדור הצעיר המנוער מתורה ויראת שמים וכשלא מוצא אוזן קשבת לדבריו עושה במחשך מעשיו, וכמה פעמים הרי אזנינו שומעות ולא זר מהמכשולים הגדולים שהנשים נכשלות ומכשילות את הרבים באיסור א”א ואנו עומדים רפה אונים באין בידינו להעמיד הדת על תלה, נדמה לי ששפיר ישנו במה שכתבתי בספרי שם כר נרחב לתת מקום לדון בכובד ראש בהערכת כל מקרה ומקרה שלטענת מאוס עלי ולהשתמש לפי הצורך בכפיה . . . ולכן לפענ”ד נאמנים המה דבריו של המהר”א טוואה בחוט המשולש שכותב שאפי’ לדעת הסוברים שלא לכוף אם יש צורך שעה בכפייה יכופו דאין לדיין אלא מה שעיניו רואות, ובלבד שתהא כוונת הדיין לש”ש ויחקור על הדבר כראוי.

R. Waldenberg concludes that the final decision on this matter should come from all the rabbinic courts in Israel. He does not want to have a situation like we have today, where different courts have entirely different approaches when it comes to how to deal with divorce law.

There is another point that is important to make. I have heard people say that the problem of the agunah that we have today, where a man refuses to give his wife a get, is a new phenomenon. This is completely incorrect, as this phenomenon is already seen in the medieval responsa. However, you won’t generally find it discussed among the responsa that deal with agunah. The matter is discussed when dealing with whether one can be forced to give a divorce. From medieval times until the present, women in unhappy marriages have demanded divorces. As we have seen, in situations that many people today would consider cases of agunah, in prior generations the rabbis ruled that the woman was not entitled to a get.

While in general both these statements are correct, it is not correct that this is always the case. For instance, let’s say the wife runs away to Europe with the kids. Does anyone seriously think that the husband is still obligated to give her a get? In such a circumstance it is entirely appropriate for the husband to insist that she come back to the United States and settle all custody issues before a get is issued. Or let’s say a husband and wife separated, and the wife refuses to let the husband see his children. It could be many months before the secular court rules on the matter of visitation. Why would anyone think that in the meantime the husband is obligated to give his wife a get if she refuses to allow him to see his children? I don’t think that there is any reputable beit din in the world that would side with the woman in these two cases. These are obviously extreme examples, and have nothing to do with the typical agunah case we hear about. Yet we should be aware that there are nuances that sometimes come into play, and every case must be investigated by a reputable beit din before judgments are made.

Finally, those who want to learn more about the matters we have been discussing should consult R. Shmuel Gartner’s detailed book, Kefiyah be-Get (Jerusalem, 1998). A 2000 page book with the title Mishpat ha-Get has just appeared. I have not yet seen it but it must have important material as well. There is also another book that is worth noting, R. Raphael Aaron Ben-Shimon’s Bat Na’avat ha-Mardut (Jerusalem, 1917). R. Ben-Shimon (died 1928) was a leading Egyptian rabbi and author of a number of significant works. What makes Bat Na’avat ha-Mardut of particular interest is that he has a number of formulations that if written today would lead certain people to claim that he was a feminist or an adherent of Open Orthodoxy. For example:

P. 4:

When reprinting rulings from R. Elyashiv that appeared in the Israeli government Beit Din publication, rather than telling the reader where they are taken from, all we get is פ”ד. Similarly, the typical reader will have no way of knowing that material has been taken from R. Ovadiah Yosef’s Yabia Omer, R. Yitzhak Yedidyah Frankel’s Derekh Yesharah, and R. Shaul Yisraeli’s Mishpetei Shaul. Obviously, for the individual who published the Kovetz Teshuvot, there is something problematic with all of these individuals, and with the government beit din, and he therefore wouldn’t even mention the name of their publications.

6. In the last post I wrote about a dispute in understanding a text between Rabbis Israel Brodie and Shlomo Yosef Zevin on one side, and Profs. Shlomo Zalman Havlin and Israel Moshe Ta-Shma on the other. I was incorrect in this, as R. Zevin actually agrees with Havlin and Ta-Shma. Thanks to Rabbi Dovid Solomon for noting this.