Some Unusually “Liberal” Statements by Mainstream Rabbinic Figures

Some Unusually “Liberal” Statements by Mainstream Rabbinic Figures

Marc B. Shapiro

I have found a number of statements by mainstream rabbinic figures that, if one didn’t know better, one would think that they were said by liberal Orthodox figures. For example:

ומה אעשה ולבי מרחם על אלמנה [ובפרט בימינו] רחמים גדולים, ואולי אפשר לערער אם אני כשר לדון דין אלמנה, אבל מצד הדין אינני רואה פסול לעצמי.

If a liberal Orthodox rabbi made this statement, I think many would say that he was not “objective” and thus not suitable to serve as a dayan. Yet the statement I just quoted was made by R. Isaac Herzog.[1]

I was surprised to see that R. Ovadiah Yosef stated that had the Hazon Ish been a dayan and seen the pain of agunot first-hand then he would have been more lenient.[2]

רבנו דיבר על החזון איש שהחמיר בענין תרי רובי בעגונות, והחמיר עוד בעניינים אחרים, ואמר רבנו אודות החזון איש, שאם החזון איש היה אב בית דין היה מוכרח להקל, כי כך אמרו הרבה שכאשר הרב מוכרח לומר דברים למעשה הוא מוכרח יותר להקל, ואמר רבנו חבל שלא עשו את החזון איש אב בית דין, כי אם היו ממנים אותו אב בית דין היה מוכרח להקל, כי הוא יושב בביתו וכותב, אם היה יושב בבית דין, והיה רואה את הנשים שבוכות כשבאות לבקש להתיר אותן וכו’ היה מוכרח למצוא צדדים להקל. ובספר אבי הישיבות אמרו על רבי חיים מוולוזין שהיה אומר בתחלה שכל עוד שלא נתמנה לאב”ד היה מחמיר בתרי רובי, ועכשיו שמינו אותו לדיין הוא מיקל בתרי רובי בעגונה.

Regarding R. Hayyim of Volozhin, who is mentioned by R. Ovadiah, see what he writes in Hut ha-Meshulash, no. 8.

שכת”ר נוטה אל החומרא מחמת שאין הדבר מוטל עליו ואף אני כמוהו לא פניתי אל צדדי היתרים העולים מתוך העיון טרם הוחלה עלי עול ההוראה והן עתה שבעוה”ר בסביבותינו נתייתם הדור מחכמים והעלו על צוארי עול הוראה מכל הסביבה שאינם מתירים בשום אופן בלתי הסכמת דעתי הקלה וחשבתי עם קוני וראיתי חובה לעצמי להתחזק בכל כחי לשקוד על תקנת עגונות.

Some people will think that the following statement, which appeals to a dayan’s emotion, is problematic:

והוא הדבר גם כאן על הדיין לראות מעצמו אם היה ענין כזה באחת מבנותיו ח”ו, ובא הבעל נגדה בטענה כזו, האם ירצה שביה”ד יפסקו עליה להוציאה בע”כ מבלי כתובה.

Yet this was said by R. Ovadiah Hadaya.[3]

In fact, words very similar to those of R. Hadaya were earlier stated by R. Hayyim Palache.[4] He explains that the Sages referred to Jewish women as בנות ישראל and not נשי ישראל in order to teach us that when a dayan and beit din deal with women in difficult halakhic circumstances, they should treat them just like their own daughters. Just like they would move heaven and earth to try to find a heter for their own daughters, so too they should do this with every woman who comes appears before them. Here are some of his words, and I wouldn’t be surprised if they are soon emblazoned on the website of ORA.

שירחם הדיין והב”ד וכל מי שהוא חכם בעל הוראה להשתדל על נשי ישראל כאלו הם בנותיו שיצאו מיריכו ובכן בבא עליהן צרה וצוקה שנעלמו בעליהן באיזה אופן שיהיה ותהיינה צרורות שישים כל מגמתו לחפש בספרי הפוסקים חיפוש מחיפוש עד מקום שידו מגעת וידיעתו מכרעת בינו לשמים אם המצא ימצא להפוך בזכותן כאלו היתה בתו ממש כדי שלא תשאר עגונא כמו שמשתדל האב על בתו?:

.The following sentence sounds very 20th century

כנראה שהר’ ז”ל [רש”י] כאב הבנות הפך בזכותן בכל ואולי מזה הצד הוסיף כפייה לחליצה שלא כדברי שאר הפוסקים.

It states that because Rashi had daughters he was led to decide the halakhah in a certain way. Although it sounds modern, it was actually stated by R. Levi Ibn Habib.[5]

Look at the following sentences that explain a dispute among rishonim about the messianic era based on the environments they were living in.

וכפי הנראה החלוקה באה מסיבת חלוקת הזמנים והמקומות שהיה לכל אחד ואחד, שהרמב”ן ז”ל היה בעת המצור והמצוק שהציקו את ישראל ואכלום בכל פה בימי הבינים בין הקתולים, לכן לא מצא מקום למלאות תקות הגאולה אם לא ביד חזקה וכפיות הרצון הנעשה ע”י נפלאות כבימי פרעה מלך מצרים. אבל הרד”ק ז”ל היה בשעתו ומקומו בין מלכי חסד ועמים רודפי צדק אשר לא שנאו את ישראל והיתה תקוה קרובה, כי ישוב לבם לטוב על ישראל.

This definitely sounds like a liberal Orthodox approach, since traditionalists do not usually say that rishonim are influenced by their environment when it comes to such an important thing as their vision of the End of Days. Yet the passage I quoted actually comes from R. Jonathan Eliasberg, Shevil ha-Zahav (Warsaw, 1897), pp. 64-65.

What about someone who writes words of praise for the woman who does not ask the rabbis if she can wear tallit and tefillin, but simply does it on her own? Believe it or not, such a sentiment is found in the writings of R. Yom Tov Algazi, who served as Rishon le-Tziyon in the 18th century.[6]

והנה בפ”ק דברכות אמרו אין עוז אלא תפילין שנא’ נשבע ה’ בימינו ובזרוע עוזו ועוד אמרי’ התם האי מאן דבעי למהוי חסידא לקיים מילי דברכות מפני שהברכות הן להמשכת החסדים כנודע והוא הנרצה באומרו עוז והדר לבושה שהית’ לובשת תפילין וטלית שנקרא עז והדר ומעיד עליה הכתוב לאמר ותשחק ליום אחרון דשכרה איתה ליום אחרון בעה”ב דאע”ג דאינה מצוו’ ועושה מ”מ יש לה שכר, דגדול המצווה אמרו מכלל דמי שאינו מצוו’ ועוש’ נמי נוטל שכר אבל אף חכמת’ עמדה לה שלא באת’ לשאול לחכמי’ אם תהי’ מנחת או”ל אלא היא מעצמה פיה פתחה בחכמ’ ותור’ חסד על לשונה שהית’ עוש’ מ”ע שה”ג שלא נצטו’ בהם מעצמ’.

If someone says that the Talmud was written by men for men and reflects a male approach in the way it is written, I would normally assume that this person is a feminist who sees patriarchy at every corner and interprets everything through the prism of gender. Yet in fact this was actually said by R. Avrohom Chaim Levin of Chicago.[7]

Even when it comes to women rabbis, I have been surprised by some of what I have found. Take a look at this rabbi’s response to a question:

אישה תוכל לכהן כרבנית קהילה?

אני לא יודע. ברור שיש ראשונים שחשבו שזה בסדר ויש כאלו שסלדו מהרעיון. רש”י על התורה מביא את דברי ‘הספרי’ על הציווי למנות שופטים: התורה אומרת ‘הבו לכם אנשים’, והספרי תמה ‘וכי יעלה על דעתך נשים?’. אנחנו אומרים: רש”י, מורנו ורבנו, על דעתך זה לא עולה? על דעתנו זה עולה. אחרי שזה עולה יכול להיות שאנחנו נוריד את זה, אבל אנחנו לא חושבים שמדובר בשיגעון או טירוף. הציווי לבנות עולם ניתן גם לנשים וגם לגברים, ‘לעבדה ולשמרה’.

This was not said by a liberal rabbi but by R. Aharon Lichtenstein.[8] R. Lichtenstein also deals with this matter in his conversations with R. Haim Sabato.[9] Here he tells us that he simply doesn’t know what will be in thirty years when it comes to women’s ordination.

איני יודע מה יפסקו פוסקי הדור בעוד שלושים שנה בשאלות סמכות נשים וכדומה. אין לי מושג . . . ידועים דברי הרמב”ם, על סמך הספרי, בעניין המינויים הפורמליים, אך יש פוסקים שלא נרתעו מכך. מה יהיה בעתיד איני יודע. אבל מה שאני יודע זה שהיום חשוב שבנות ישראל תדענה תורה, שתהיינה דבקות בתורה. לגבי כל השאר איני אומר בדיוק. בהדי כבשי דרחמנא למה לך

His position, which recognizes the possibility of change in this matter guided by Modern Orthodox/Religious Zionist halakhic authorities, is much more nuanced than what we have been hearing recently. R. Lichtenstein recognized that changes occur and he was honest enough to admit that he didn’t know what the future will bring.

R. Norman Lamm has also stated that he doesn’t know if women will be ordained, and that his opposition to women’s ordination is “social, not religious.”[10] In another interview he took the middle ground, saying that he doesn’t know if it is halakhically permissible for women to become rabbis, but he also doesn’t know if this is forbidden.[11]

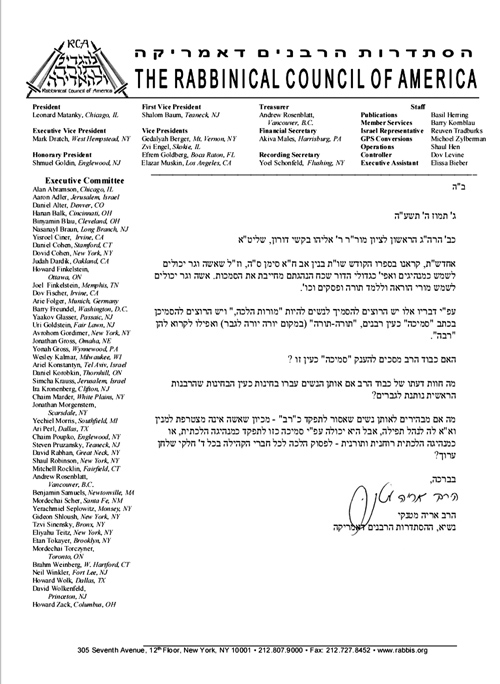

Regarding the general matter of women’s ordination, I have already commented on it here.[12] Let me just add that I think I have read everything coming out of the RCA and its people in the last few months, and I confess that I still don’t see the objection to female clergy. I am not talking about women pulpit rabbis, but what is the problem with a woman chaplain at a hospital or a woman teacher of advanced Torah studies or even a woman posek (poseket)? I realize that there are objections to using the title of “rabbi” for women, and Saul Liebeman focused on this in his letter of opposition. So why not just come up with a different title?

The RCA is apparently opposed to giving learned women any title. However, titles are important, as they are community recognition that someone has reached a certain level. There are women who are learned and it is only fitting that they too have a title. In fact, some women who went into academic Jewish studies would have been just as happy to remain in traditional Jewish studies if there was some way of recognizing their achievements. And before you start putting down the importance of titles, I can tell you that there are learned (and not so learned) men who use the title “rabbi”, even though they have never received semikhah. They do so because they feel the title is important for their community work. By the same token, a title can also be important for women who are involved in teaching Torah and community leadership.

As for the title of “rebbetzin”, or “rabbanit” in modern Hebrew,[13] this has no appeal for many of the Modern Orthodox, as I have mentioned here. This point is also seen in a recent comment by Yakir Englander and Avi Sagi, that the title “rabbanit” is used to create a halo of authority where none exists.[14] Yet as I note in the just mentioned post, there is biblical precedent for calling women by their husband’s title. I subsequently saw that in Shabbat 95a, Rashi, s.v. אשה חכמה claims that אשה חכמה here does not mean a learned woman but the wife or daughter of a scholar who would have picked up some knowledge by virtue of her family situation.[15] Isn’t this the same thing with rebbetzins in the haredi world? Simply by being married to a rabbi they end up more Jewishly learned, especially in practical halakhah, than the typical haredi woman.

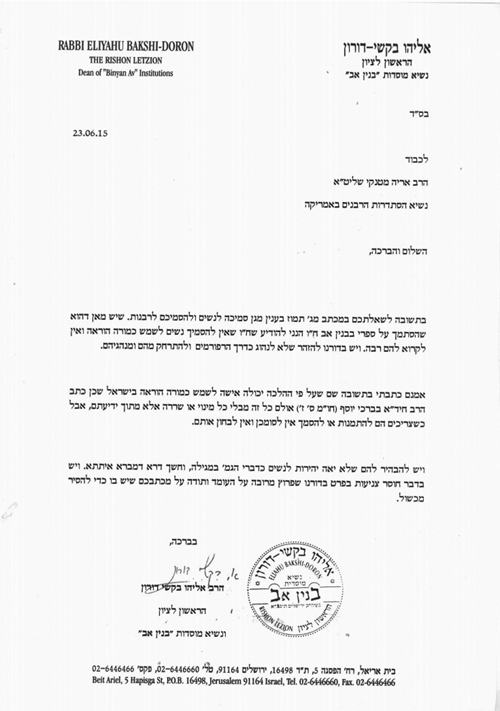

For a long time the ones pushing women’s ordination have pointed to a responsum by R. Eliyahu Bakshi-Doron, Binyan Av, vol. 1, no. 65, in which he affirmed that women could be poskot. Here is his conclusion.

I have already noted here that very few rabbis are poskim, but every posek is by definition a rabbi. And since R. Bakshi-Doron is telling us that a women can be a posek, it is easy to see why this responsum has been cited again and again in support of women rabbis. This led the RCA to turn to R. Bakshi-Doron for clarification as to whether he indeed supports women’s ordination. Here is the RCA letter[16] and R. Bakshi-Doron’s response

As you can see, he strongly rejects the notion of women rabbis, seeing this as a Reform innovation. He also says that while women can function as poskot, they cannot be appointed to any such position in an official way, and thus a rabbinic position is also out of the question. (So again I ask, what would be the problem with a woman being given a title if she served as a chaplain or teacher? This does not contradict what R. Bakshi-Doron says.[17]) R. Bakshi-Doron concludes his letter as follows:

ויש להבהיר להם שלא יהא יהירות לנשים כדברי הגמ’ במגילה, וחשך דרא דמברא איתתא. ויש בדבר חוסר צניעות בפרט בדורנו שפרוץ מרובה על העומד ותורה על מכתבכם שיש בו כדי להסיר מכשול.

Rabbi Gordimer did a post on R. Bakshi-Doron’s reply. In it, he translated the last sentence of the final paragraph of R. Bakshi-Doron’s letter.

There inheres in the matter (of women serving as rabbis and licensed halachic authorities) a lack of modesty, especially in our generation, in which immodesty is more prevalent than modesty. I thank you for your letter, which has enabled me to remove a source of misinformation.

Rabbi Gordimer did not translate the final paragraph in its entirety. The first part of it states: “It should be explained to them that haughtiness is not fitting for women, as stated by the Gemara in Megillah.” The exact reference is Megillah 14b.

If this wasn’t enough for the Orthodox feminists to stop citing R. Bakshi-Doron, then his next words will be. He wrote וחשך דרא דמברא איתתא. The first thing to note is that there is a typo here and דמברא should read דמדברא. The source of this passage is Midrash Tehillim 22:20 where it states: חשיך דרא דאתתא דברייתא. This means, “Woe unto the generation whose leader is a woman.” This is definitely not the sort of thing that a typical RCA rabbi would feel comfortable putting in print, or announcing from the pulpit. For those arguing against women rabbis this kind of sentiment would hurt, not help, the cause. I think this is the reason why the RCA has not released a translation of R. Bakshi-Doron’s letter, and as noted, Rabbi Gordimer didn’t provide a complete translation either.

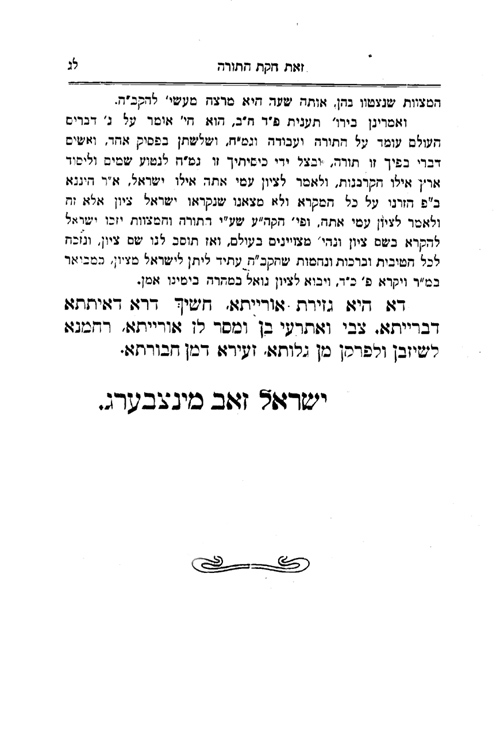

To give an example of how this passage from Midrash Tehillin has been used in the past, R. Yisrael Zev Mintzberg published his Zot Hukat ha-Torah in Jerusalem in 1920. This work is devoted to showing that women are not permitted to vote. Look how he cites the passage in his conclusion on p. 33.

R. Hayyim Hirschensohn referred to this passage as well, in his strong attack on R. Mintzberg in which he goes so far as to say that the latter does not even permit women to be women.[18]

ואחד מרבני ירושלים הרה”ג מוהר”ר ישראל זאב מינצבערג נ”י יצא בקונטרס “זאת חוקת התורה” אשר חוקה הוא חוקק גזרה הוא גוזר בכח הפלפול ובכח הקבלה ובכח האגדה לשלול כל זכיה מנשים אפי’ מלהיות נשים, כל ההולך בעצת אשתו נופל בגהינם, אינון מסיטרא דדינא קשיא, חשיך דרא דאיתתא דבריתא, דא היא גזירת אורייתא, ואי אתה רשאי להרהר אחריה.

R. Shlomo Zalman Ehrenreich also cites the phrase חשיך דרא דאיתתא דברייתא in order to make the following point:[19] Women were not created to bring others to Torah. Rather, their role is to enable their husbands to reach perfection.

האשה לא נבראת לטהר אחרים לאביהם שבשמים כדאיתא במגילה י”ד לא יאי יוהרא לנשי ובמדרש שוח”ט חשיך דרא דאיתתא דברייתא הובא בילקוט שמעוני שופטים ב’ ע”ש. ולפמש”כ דכל עיקר האשה הוא רק לתכלית שהבעל יתקדש על ידה.

Finally, when it comes to the matter of women rabbis, I think people will find the following amusing, or disturbing. There are liberal Muslims in Israel, and these are the people that Israel should be supporting. Recently, a Muslim member of Kenesset, Issawi Frej, journeyed to Bnei Brak to try to convince some leading rabbis to support the appointment of women qadis. The problem is that Minister Yaakov Litzman of the Yahadut ha-Torah bloc is strongly opposed to appointing women as qadis, because he fears that this will then lead to pressure for recognition of women rabbis. Knowing that Litzman and the other haredi Kenesset members take their orders from the rabbis, Frej understood that he had to convince the rabbis of his position. Yet unfortunately for Frej and liberal Muslims as whole, and I think for the rest of us as well, the Bnei Brak rabbis he met with refused to budge. See the story here.

Regarding the issue of yoatzot, I don’t want to get into that in any detail, but I do want to call readers’ attention to the following which surprisingly has not been referred to by any of the supporters of yoatzot. In the Leket Yosher (pp. 35-37 in the Machon Yerushalayim edition) we can see a yoetzet in action. A woman wrote to the wife of R. Israel Isserlein with a halakhic question. The wife inquired from her husband, R. Isserlein, and then replied to the woman. Had she already known the answer she would not have had to ask her husband. This is exactly what yoatzot do in the 21st century. Here is the text.

There is also a text in Niddah 13b that refers to what we can term a yoetzet, yet I have also not seen it cited.

אמר רבי חרשת היתה בשכונתינו לא דיה שבודקת לעצמה אלא שחברותיה רואות ומראות לה.

Rashi explains:

ומראות לה: שהיתה בקיאה במראה דם טמא ודם טהור.

Let me now return to the matter of halakhic decisions and ideology. As mentioned, Rabbi Gordimer is mistaken in stating that Modern Orthodox poskim evaluate matters the same way as haredi poskim. They don’t, and this isn’t even something that they should aspire to. Does this mean that a posek’s general ideology should disqualify him in some people’s eyes? For example, if someone is a recognized posek, does the fact that his ideology on Zionism is diametrically opposed to yours (e.g., R. Moshe Sternbuch) mean that you shouldn’t ask him questions?

Historically, ideological matters were kept separate from halakhah. The various rabbinic organizations in Europe and the United States were comprised of rabbis who held different views about Zionism and other matters. If you were a Mizrachi supporter but the rav of your town was an Agudist, you still asked him all of your halakhic questions, because he was your rav. By the same token, if you were an Agudist and the rav of the town was Mizrachi, he was still the one to answer your halakhic questions. This is how matters worked in Lithuania and Poland and then in the United States. One of the unfortunate results of modern haredi Judaism (and it has precedents in Germany and Hungary) is that this model was destroyed.

A basic feature of “official” haredism, especially in Israel, is the attitude that even if someone is a great posek, he is still disqualified if he doesn’t follow the correct Da’as Torah. It is hard to imagine a greater degrading of respect for Torah scholars than this (which thankfully is not shared by all who identify as haredim, even though it is reflected in all the Israeli haredi newspapers and “official” publications). It is precisely this approach, that of degrading one’s ideological opponents despite their great Torah knowledge, that stands at the root of all the terrible disputes in the haredi world. It also explains why, in recent years, haredi figures and newspapers felt that it was OK to speak so inappropriately about outstanding sages such as R. Ovadiah Yosef, R. Meir Mazuz, R. Shlomo Amar, R. Aharon Leib Steinman, and R. Shmuel Auerbach.

Unfortunately, this approach has now entered the Sephardic world as well, where in the last Israeli elections we saw the worst aspects of Ashkenazic haredi society, i.e., personal denigration for ideological reasons, arise for the first time in the Sephardic world. I will discuss this in detail in a future post when I speak about R. Mazuz’s religious and political outlook, his role in the last Israeli elections, and the vicious things said about him and his yeshiva.

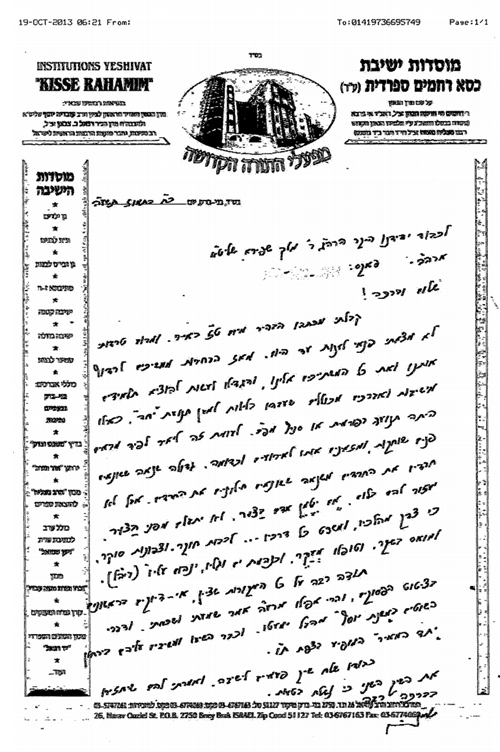

While it is true that it was Ashkenazim who began the personal denigrations, it is a Sephardi, R. Shalom Cohen, who brought it to a new low. I will discuss this in the upcoming post, but for now, suffice it to say that for all the Ashkenazic haredi disrespect for opponents, I don’t know of anyone who has referred to an opponent’s yeshiva in the way R. Cohen referred to R Mazuz’s Yeshivat Kise Rahamim, a yeshiva that has educated thousands of students and today is of much greater significance than R. Cohen’s Porat Yosef. For those who haven’t heard, and it is difficult for me to even repeat this, R. Cohen publicly referred to the great Kise Rahamim yeshiva as a בית הכסא. Can anyone imagine a more disgraceful statement about a place of Torah? This is what happens when people think that they can degrade those who don’t adopt a certain Da’as Torah perspective.

Here is a letter I recently received from R. Mazuz, which I publicize with his permission.

In it he states:

גדולה שנאה ששונאים חרדים את החרדים משנאה ששונאים חילונים את החרדים.

It is unfortunate that the disqualification of great Torah scholars due to ideological reasons has also been seen in the Religious Zionist world, though not to the extent that it is found in the haredi world. For some Religious Zionist figures, haredi poskim are disqualified in the exact same way that haredim disqualify Religious Zionist poskim. R. Dov Lior quotes R. Kook as stating that the rabbis we today refer to as haredim cannot arrive at the truth of Torah in any matter.[20]

שמי שחי בדור שלנו ואינו מביט אל האור הזרוע של תהליך גאולת עם ישראל, לא יוכל לכוון בשום דבר לאמתה של תורה. גם אם הם יכולים להתפלפל בעניייני שור שנגח את הפרה, בענייני ההנהגה של כלל ישראל הם לא מכוונים לאמיתתה של תורה.

R. Lior’s statement was made in response to haredi indifference to the Gush Katif expulsion, and he claims to be simply citing R. Kook. Yet if we look at R. Kook, Iggerot ha-Re’iyah, vol. 2, no. 378 (p. 37), we find that R. Kook’s statement is much narrower, and I have underlined the point that R. Kook focuses on.

ואם יבא אדם לחדש דברים עליונים בעסקי התשובה בזמן הזה, ואל דברת קץ המגולה ואור הישועה הזרוחה לא יביט, לא יוכל לכוין שום דבר לאמתתה של תורת אמת.

Even R. Lior’s statement is not entirely clear, since he begins by saying that the haredi rabbis can never arrive at Torah truth, but in the end he only seems to be referring to Torah truth when dealing with communal and national matters. R. Kook would agree with this latter point, but I know of no evidence that he would say that in general the haredi rabbis can never arrive at Torah truth.

R. Zvi Yehudah Kook, basing himself on the same letter of R. Kook cited by R. Lior, stated that one should not ask a haredi posek any halakhic questions.[21]

רבנו לימד את אגרת שע”ח: “ואשר יבוא לחדש דברים עליונים בעסקי התשובה ואל דברת הקץ המגולה ואור הישועה הזרוחה לא יביט, לא יוכל לכוון שום דבר לאמתתה של תורת אמת”. הוא הסביר: “עסקי תשובה – הכוונה לדברים כלליים”. תלמיד שאל: “האם בהלכות שאינן נוגעות לענייני תשובה ואמונה ושאר דברים כלליים – אפשר לשאול רב חרדי”? רבנו הגיב חדות: “הדברים ברורים! מה כוונתך?” התלמיד חזר ושאל: “למשל, האם אפשר לשאול רב חרדי בהלכות בשר וחלב”? רבנו דפק על השולחן והגיב בתקיפות: “חרדיות זה מיעוט אמונה, ומיעוט אמונה זה עקמומיות בשכל, ועקמומיות בשכל צריכה בדיקה.”

This is just the flip-side of the common haredi position that one should not ask a Religious Zionist posek any halakhic questions. As mentioned already, the haredim were the first to push this approach, and I find it unfortunate that some Religious Zionist leaders have responded in kind.

Coming soon: R. Hershel Schachter on poskim as communal leaders, a newly discovered letter from R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg in which he praises R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik, and a previously unknown picture of R. Moshe Feinstein and R. Soloveitchik.

[1] Pesakim u-Khetavim, Even ha-Ezer, no. 229 (p. 1291).

[2] Rabbenu, p. 191.

[3] See R. Ovadiah Yosef, Yabia Omer, vol. 3, p. 300. R. Ovadiah Yosef does not agree with R. Hadaya’s sentiments.

[4] Hayyim ve-Shalom, vol. 2, Even ha-Ezer, no. 1 (p. 2a).

[5] She’elot u-Teshuvot ha-Ralbah, no. 36.

[6] Kedushat Yom Tov (Jerusalem, 1843), p. 87b (emphasis added). This passage was noted by Zvi Zohar in Akdamot 17 (2006), pp. 81-82. He mistakenly identifies the author as R. Israel Jacob Algazi, the father of R. Yom Tov.

[7] This is recorded in R. Yona Reiss’s shiur, “Women’s Issues in Halacha: Female Rabbis, Torah for Women, Saying Kaddish & Bat Mitzvas,” available here, beginning at 18:30.

[8] See here (called to my attention by Marc Glickman).

[9] Mevakshei Panekha (Tel Aviv, 2011), p. 177. The passage below from R. Lichtenstein comes from this page.

[10] See here.

[11] See here.

[12] Regarding the matter of women dayanim that I discussed here, see also R. Jonathan Eliasberg, Darkhei Hora’ah (Vilna, 1884), part 2, ch. 8. R. Eliasberg thinks that a woman can be a dayan, but she cannot be a dayan together with men.

דלעולם אשה כשירה לדון אלא דכמו דאשה חייבת בזימון (להאי שיטה) ומ”מ אינה מצטרפת עם אנשים ועקרו חכמים בשוא”ת משום פריצותא מכש”כ דאשה אינה מצטרפת עם עוד שני דיינים משום פריצותא. אבל לעולם אשה שהיא מומחית כיחיד מומחה דנה וכן ג’ נשים דנות וא”כ א”ש הכל דדבורה ע”כ דדנה ביחידי.

[14] Guf u-Miniyut be-Siah ha-Tziyoni-Dati he-Hadash (Jerusalem, 2013), p. 123.

[15] R. Meir Mazuz, Asaf ha-Mazkir, p. 115, calls attention to JShabbat 13:7:

דאמר ר”ש בי רבי ינאי אני לא שמעתי מאבא אחותי אמרה לי משמו ביצה שנולדה ביום טוב סומכין לה כלי בשביל שלא תתגלגל אבל אין כופין עליה כלי.

[16] It is strange that the RCA stationery used in June 2015 still listed Barry Freundel as a member of the Executive Committee, even though at that time he was in prison.

[17] R. Bakshi-Doron might see women rabbis as forbidden due to the prohibition of serarah for women. I haven’t seen this point mentioned by RCA figures, and it is difficult to see the modern position of rabbi as having anything to do with serarah. Regarding this matter, see R. Aryeh Frimer, “Nashim be-Tafkidim Tziburiyim bi-Tekufah ha-Modernit,” in Itamar Warfhaftig, ed., Afikei Yehudah (Jerusalem, 2005), pp. 330-354. On p. 345, R. Frimer cites R. Eliezer Silver’s hiddush that there is no issue of serarah in the Diaspora. On p. 346, he cites R. Isaac Herzog’s view that there might not even be an issue of serarah today in the Land of Israel. See also p. 353 where he prints a 1986 letter he received from R. Shaul Yisraeli that is almost prophetic, since in those days no one in Orthodoxy other than Blu Greenberg was even considering the matter of women rabbis. While R. Frimer had argued in favor of including women on religious councils in Israel, R. Yisraeli responded as follows:

כבודו מדבר על השאלה הספציפית של חברות במועצה הדתית. האם כבודו חושב, שבזה יגמר הדבר? הן כבר עיננו רואות את המפלגות החילוניות שעטו על המציאה, וכולם נעשו לפתע מעונינות למנות את נציגיהם, יותר נכון – נציגותיהן, לגוף הבוחר של רב הראשי לתל-אביב. הן לא נטעה, שמחר-מחרתיים, תופיע דרישה למנות “רבנית” במקום “רב”. והרי גם לזה לא קשה למצוא סימוכין – דבורה הנביאה וחולדה הנביאה.

[18] Malki ba-Kodesh, vol. 2, p. 172.

[19] R. Hayyim ben Betzalel, Iggeret ha-Tiyul, ed. Ehrenreich (Jerusalem, 1957), p. 90.

[20] Devar Hevron: Hashkafah ve-Inyanei Emunah (Kiryat Arba, 2011), p. 232 (emphasis added).

[21] Iturei Yerushalayim, Sivan 5769, p. 5.