Announcement – Lecture by Rabbi Yechiel Goldhaber at the Sprecher home

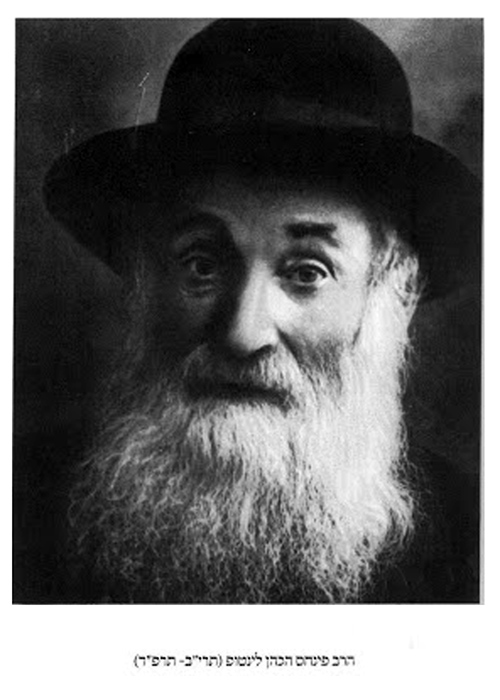

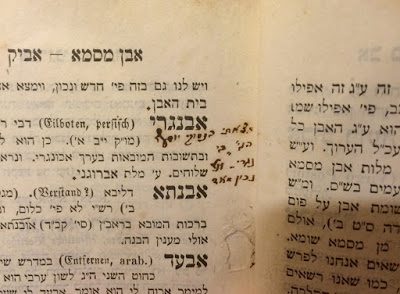

Maimonides and Prophecy, R. Pinhas Lintop, R. José Faur, and More Examples of Censorship

Regarding this issue, see also R. Kafih’s commentary to Guide 2:33, n. 5, where he writes:

Further discussion of this matter, where R. Kafih elaborates on what he only hinted at elsewhere, can be found in his She’elot u-Teshuvot ha-Rivad (Jerusalem, 2009), nos. 24-26, where he explains to R. Mazuz what Maimonides had in mind.

In previous writings (books, articles, and posts), I have called attention to many examples where Maimonides writes things that he does not actually believe, so what we have just seen is nothing new. The significance of the example I have mentioned is that R. Kafih accepts this approach as a valid method of explaining a formulation of Maimonides in the Mishneh Torah. For another example from R. Kafih, see his note to Guide 2:45 (p. 268), where he writes:

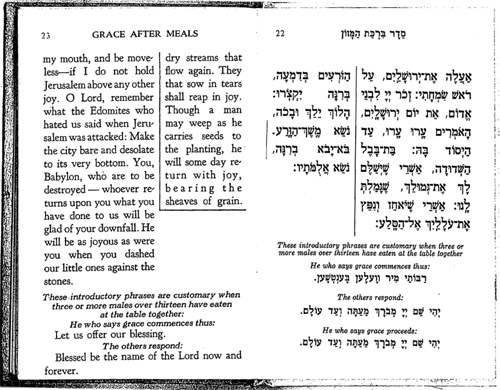

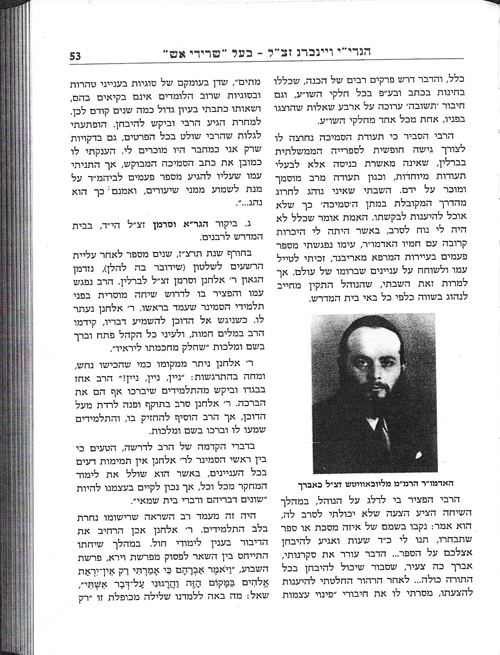

The picture I referred to is the following, from R. Abraham Weingort, ed., Haggadah Shel Pesah al Pi Ba’al ha-Seridei Esh (Jerusalem, 2014), p. 53.

The Hebrew passage just quoted begins by stating that the comment in Zikhron Yehudah that one can take off one’s head covering if it is hot was added by “those who are bareheaded”.[15] This is followed by a quotation from the manuscript in which R. Judah says that on hot days he would sit with a lighter head-covering than normal. However, even this version has the language וטוב שלא לישב בגלוי ראש which also implies that there is no prohibition to be bareheaded during Torah study. This manuscript also has ולפעמים מפני כובד החום נראה להקל, which implies that one can be completely bareheaded if it is hot, to which it then adds that R. Judah himself did not sit bareheaded but wore a lighter head-covering. I therefore don’t see any substantial difference between the two versions of the responsum, yet the unnamed גאב”ד did see a problem with the first version and assumed that the text had been tampered with by a heretic.

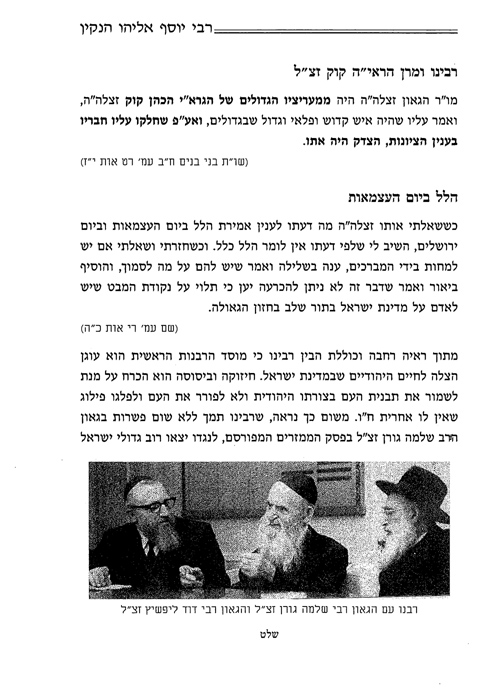

The second document is a 1969 letter from R. Abadi to Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Nissim defending R. Faur. I found this document in the R. Nissim archive at Yad ha-Rav Nissim in Jerusalem. Together with the letter is a note that provides the following identifications.

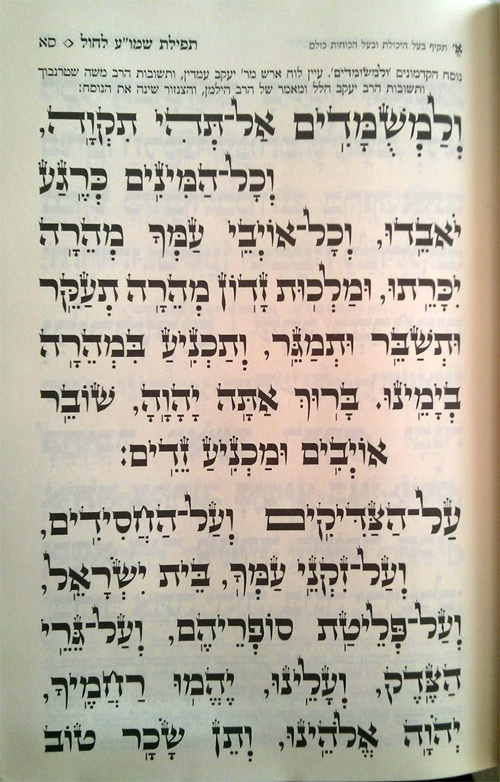

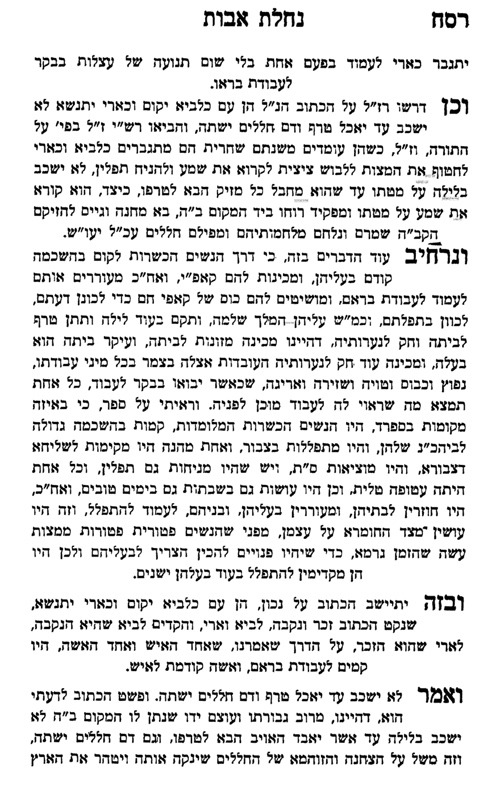

In 2015 the multi-volume set of Nahalat Avot was reprinted in Jerusalem. Take a look at the following page and you will see that the passage dealing with the women’s prayer groups has been deleted in its entirety.

אכן השם שלו היה חיים שימי, ואין זה קיצור חיבה של ‘שמעון’ (כמובן לא היו עושים כן על מצבה). הוא נקרא כך, למיטב ידיעתי, על שם סבתו (אם-אמו, חותנתו של הרב הענקין) שימא קריינדל, שנפטרה כשנה וחצי לפני הולדתו.

פעם שאל אותי חסיד אחד, מילא לקרוא לבן ע”ש בת אינו חידוש ומצאנו כן במעלה הדורות, אבל להמציא בשביל זה שם חדש, היכן מצאנו דבר כזה אצל שלומי אמוני ישראל?! והשבתי לו, אולי הגמרא לא מלאה ברב שימי בר אבין [צ”ל אשי] וכיו”ב?

Ron C. Kiener claims that the following passage in Zohar Hadash 27d is referring to Muslim control of the Temple Mount. Its view is exactly the opposite of what we saw in Pitron Torah:

אבנא אבנא אבנא קדישא עילאה על כל עלמא בקדושתא דמארך זמיני בני עממיא לאתזלזלא בך ולאותבא גולמי מסאבין עלך לסאבא אתרך קדישא וכל מסאבין יקרבון בך ווי לעלמא בההוא זמנא

Oh stone, oh stone! Oh holy stone, greater in the world in the holiness of your Master. In future times the nations will humiliate you and place upon you defiled objects, defiling your holy place. And all the defiled ones will come unto you. Woe to the world at that time!

Translation by Kiener, “The Image of Islam in the Zohar,” Mehkerei Yerushalayim be-Mahashevet Yisrael 8 (1989), p. 51.

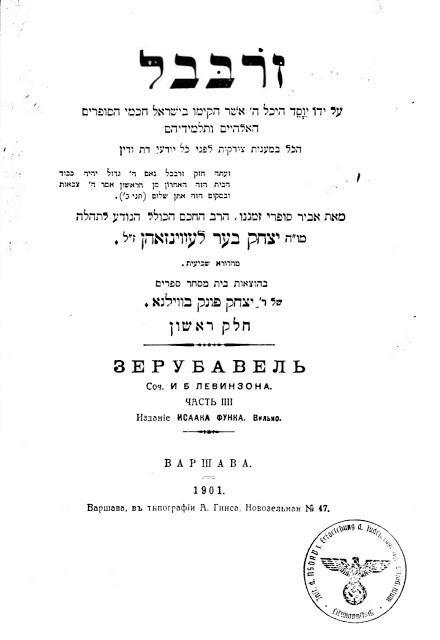

Finders Keepers? The Itinerant History of Strashun Library of Vilna, Pt I

History of Strashun Library of Vilna

by Dan Rabinowitz

Allies’ post-war efforts that led to the locating some of these looted treasures. While some of the best-known examples of these recovered treasures are related to art, gold, or Swiss bank accounts, Hebrew books were also part of the Nazi’s appropriation scheme and were included in the items recovered after World War II. Some of the books recovered belonged to a unique institution, the first Jewish public library, and tracing the journey of these books, up to present day, parallels that of its patrons, tortured, uncertain, and yet despite all odds, surviving.

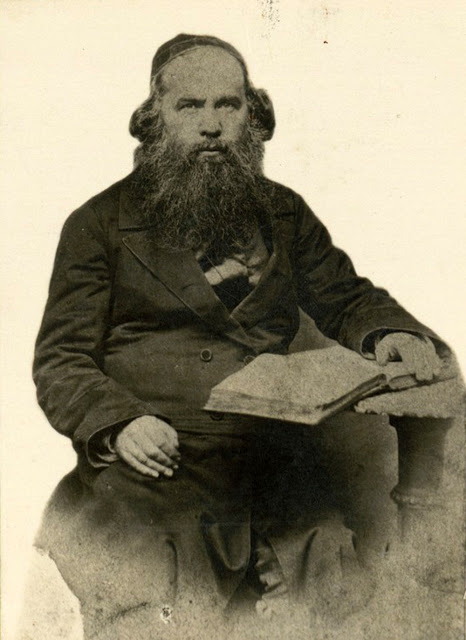

impressive, as his notes cover nearly every single page[3] of the Talmud Bavli.[4]

New York) among them, eulogized Strashun.[11] Posthumously, a street in Vilna was named after him.[12]

lasting legacy beyond that of any actual blood descendants.”[23]

lock and key” and were available only to those with special access.[24] It remained in this state even though there were trustees and enough money to cover its operations.[25] Although the

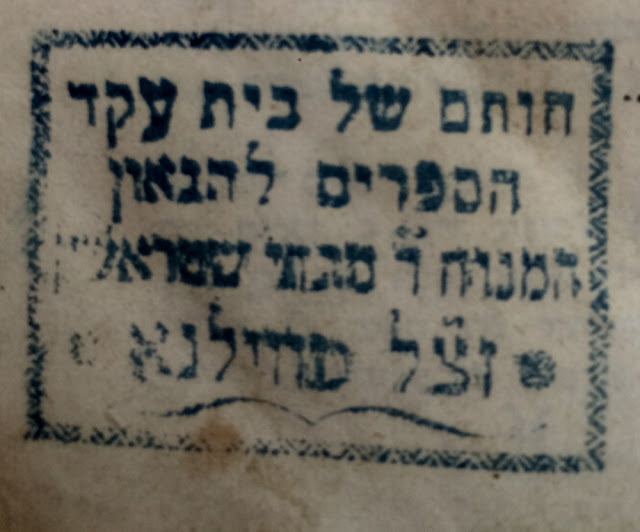

library did not open to the public, the trustees were not idle during this time; and in 1889, published a complete catalog of Strashun’s collection. His collection was comprised of 5,753 items, 63 of which contained marginalia in his hand.[26]

after the library was opened to the public, in legal documents, the listed owner was not the Vilna community but one of the Library’s trustees. Although Strashun’s intent was clear – that the Library belonged to the community and not a trustee or any other individual – the Library’s legal status clouded that directive. In the late 1890s, there was a successful campaign to correct that issue, and the community becomes the sole owner of the Library, fulfilling Strashun’s wishes regarding ownership.[28]

point forward, the Strashun Library would be one of Vilna’s most important institutions.

infrastructure and clarifying ownership.

Specifically, although Strashun’s collection was substantial both in

terms of size and breadth, it was still the product of one man’s idea of a library. For this reason, Hillel Noach Steinschneider, one of Vilna’s leading scholars and historians, pleaded with the public to donate books and ensure the completeness of the library and fulfill its mission of serving the entire community. He acknowledged that Strashun amassed a very impressive private collection, but that for a public library his collection alone was insufficient because “it is lacking in books for people” whose interests did not align with Strashun’s.

That is, a public library is not only a place open for all but also one that provides value for all. Consequently, the library’s composition must reflect the entirety of its audience and not a single collector. Apparently, this plea was successful,[30] many Vilna scholars donated their collections to the Library in addition to the general public, and, by the 1930s, the Library had grown to over 35,000 volumes.[31] Additionally, Vilna’s Tzedakah Gedolah organization also provided funds for acquisitions. Books acquired through those funds contain a special stamp or receipt.

works” and who sat side-by-side with the “younger generation who were reading haskalah works.”[33] When dignitaries came to Vilna, the Strashun library

was a waypoint.[34]

Jewish celebrities, but also for its well-regarded holdings. According to A.J. Heschel, it was the largest public Hebraic library in Eastern Europe reported holding over 40,000 volumes.[37] On the one hand, the Strashun library was recognized as one of the greatest cultural institutions in Eastern Europe, on the other, like so many public institutions, the Library struggled to raise sufficient funds throughout the early part of the 20th century, consistently hampering its ability to maintain and build its

collections in addition to limiting its public access.[38] But, it would not be funding that led to its demise but the Nazis and their campaign to appropriate Jewish cultural treasures.

of those compared to the Nazi’s systematic campaign to identify, collect, and appropriate important Jewish treasures –specifically books – and, consequently, important libraries. The intent was that these pillaged libraries would supplement the already substantial Judaic holdings of Frankfort City Library.[40] Immediately after the Nazis occupied Vilna, the Strashun Library as Vilna’s “oldest and perhaps most distinguished” library was identified as a target for this campaign.[41]

libraries, both public and private that ended up at Offenbach, without any clear method of repatriation. This lack of clarity leads to inconsistent results at best. Indeed, first-hand accounts of post-war Germany confirm the ad-hoc, doubtful legal grounds and sometimes completely lawless reparation regime in the post-war chaos. In many instances, individuals made many of the decisions regarding disposition with little information and virtually to no oversight.

half of the heirless Jewish books recovered by the Allies went to the Jewish National and University Library (“JNUL”) at the Hebrew University (now the National Library of Israel),[50] which was “quite right” because some unnamed person or entity had determined “that clearly the [JNUL] should take the place of the vanished Jewish communities of Europe.”[51]

and did everything in his power, including employing very underhanded means, to repatriate items to Hebrew University.[52]

could not remove any items. But, for Scholem, some items proved too enticing. Scholem identified a number of rare and important books and manuscripts. He was concerned that if the disposition of these items were left to the Allied authorities the items would not end up in Jerusalem, but, instead, at the Jewish Theological Seminary, or some other institution, in the United States. This was unacceptable to Scholem. To facilitate the transfer of these items to the JNUL, Scholem colluded with a Jewish American serviceman to smuggle the works out of Offenbach. Scholem placed the collection into five boxes but did not label

their contents and provided a fake name on the invoice. The American serviceman personally ensured that the boxes were shipped to Paris, after which they were sent to the JNUL. Eventually, the Allies found out about the theft, and demanded the return of the five boxes, even lodging a formal diplomatic complaint. In the end, after much back and forth, the boxes remained at the JNUL.[54]

After WWII, on behalf of the Jewish Distribution Committee after World War II, she went to the Offenbach Depot to assist with identification of heirless books. Prior to coming to Offenbach, she had “promised [herself] that [she] would do [her] best to

safeguard the rights of possible owners and heirs.”[57] And, when she came upon some of the remains of the YIVO collection,[58] she “was in a state of exaltation” and in a letter home wrote that she “had ‘a feeling akin to holiness, that [she] was touching something sacred.’”[59]

strange story” that the head of YIVO, Max Weinreich,[60] had told her “back in 1940.” Weinreich told her that during the brief period of time when the Soviets had returned Vilna to Lithuanian control, YIVO attempted to move its library out of Vilna.[61] And, that “the trustees of the Strashun Library, also fearing for the sake of their library, asked the Vilna YIVO to ship [the Strashun Library] too.” Unfortunately, the shipment never occurred and both libraries remained in Vilna and ultimately plundered by the Nazis.

rescued from the ruins of Europe and brought back to YIVO in New York in 1947.”[64] YIVO’s library catalog again implies that all the recovered books went to YIVO and links the disposition of the Strashun Library with that of YIVO’s, the provenance note explains that “[t]he Strashun Collection, along with the YIVO Vilna collections, were liberated by the American Army, and

re-repatriated to YIVO in New York in April 1947.”[65]

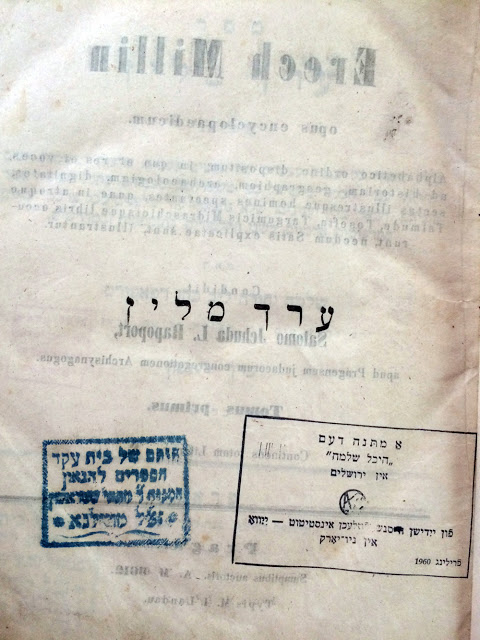

Mekorei Rambam, first published in 1870 in Vilna, and while not a true stand-alone work, Rashash’s comments appear

alone, without the Rambam’s text. See Mekorei ha-Rambam, Harkavy ed., (Jerusalem, Hatsa’at ha-Sefarim ha-Erets-Yisre’elit, 1957, Im ha-Madurah, and p. 59.

n.10. First, Zalkin, cites Strashun’s comment in Gitten 6b, that “we find many amora’im who did not know how to read scripture” as proof of his “unorthodox” views. But we find a similar statement from the medieval period. See Tosefot, Bava Batra, 113a. Zalkin’s second citation is to Rashas’s comments, Rosh ha-Shana 26a, “certain things that were uttered in a particular time and particular place are inserted by editors of the Talmud in their appropriate location in the text.” This misrepresents the Rashash. Rashash is attempting to answer how the Talmudic sage, Levi, was unaware of an explicit verse as the TB in RH 26a implies. Rashash explains that although there is no explicit mention of the time or place that this story occurred, Rashash posits that the story in Rosh Hashana occurred at the same time as another story with Levi, Yevamot 105a, where he had a moment of senility.

Rashash is not offering his opinion regarding the redaction of the Talmud, instead he is merely dating the story in Rosh ha-Shana. Finally, it is unclear the relevance of Zalkin’s third example, “you will find many contradictions between different locations is (sic) Rashi’s text.” Locating and alleging contradictions in Rashi is hardly remarkable.

Strashun Z’L, in Mattiyahu Strashun, Matat-Ya, Haghot, Hidushim ve-He’arot Me’irot ‘al Midrash Raba Pri Eito Shel Matityahu Strahsun, (Vilna: The Widow and Brothers Romm, 1893), 15.

(Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press, 2006), 48-52.

See Likutei Shoshaim, nos. 386,1024,1178, 2522, 3352, 3650, 3781, 4377, 5399, 5592. Regarding other well-known Hebrew book collectors and their collections, see Alexander Marx, “Some Jewish Book Collectors,” in his Studies in Jewish History & Booklore, (New York, 1941), 198-237; Cecil Roth, “Famous Jewish Book Collections & Collectors,” in Essays in Jewish Booklore, (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1971)330-35.

Alexander Marx, “Some Notes on the History of David Oppenheimer’s Library,” Revue des Études Juives 82 [=Israel Lévi

Festschrift] (1926): 451-460; Charles Duschinsky, “Rabbi David Oppenheimer: Glimpses of His Life and Activity, Derived from His Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library,” Jewish Quarterly Review 20:3 (January 1930): 217-247; Alexander Marx, “The History of David Oppenheimer’s Library,” in Studies in Jewish History and Booklore (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1944), 238-255; and more recently in Joshua Teplitsky, “Between Court Jew and Jewish Court: David Oppenheim, The Prague Rabbinate, and Eighteenth-Century Jewish Political Culture (PhD dissertation, New York University, 2012); and Abraham Schischa, “Rabbinic Writings from the Collection of Rabbi David Oppenheim,” Yeshurun 31 (2014): 781-794 (Hebrew).

Treasured Legacy (Clevland/Jerusalem: Ofeq Institute, 1990) 66-67.

appearing in Yoreh De’ah. Because Wallensky’s materials were even more obscure and rare, the only place he could access these was the Strashun Library. Ya’akov Wallensky, Daltei Teshuva, (Vilna, 1890), Introduction, 5-6, (link).

comprised of 5,739 items.

346.

venerable long-bearded men, wearing hats, studying Talmudic texts, elbow to elbow with bareheaded young men and even young women, bare-armed sometimes on warm days, studying their texts. The old men would sometimes mutter and grumble about what the world had come to. The young people would titter.”).

Lithuania,” in Yahdut Lita (Tel Aviv: Am Hasefer Publishers, 1950), 522 (Hebrew). For a photo of one such visit, see Layzer Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, vol. 2 (New York: Laureate Press, 1974), 416.

(New York, 1935 – in Yiddish), p. 286-7

States: Oxford University Press, 2015), 121.

Dicker, Of Learning and Libraries, The Seminary Library at One Hundred, (New York: The Jewish Theological Seminary, 1988), Appendix B. See also F.J. Hoogewoud, The Nazi Looting of Books and its American ‘Antithesis’. Selected Pictures

from the Offenbach Archival Depot’s Photographic History and Its Supplement,” Studia Rosenthaliana 26:1-2 (1992): 158-192; and F.J. Hoogewoud, “Dutch Jewish Ex Libris found among looted books in the Offenbach Archival Depot (1946),” in Chaya Brasz and Yosef Kaplan, eds., Dutch Jews as Perceived by Themselves and by Others (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 247-261.

Id. 248; 351.

no real harm.” One wonders if any surviving heirs who had legal claims to the Manheim collection would reach the same conclusion.

library and not the property of one institution or another. See Shor, From “Likutei Shoshanim”, at 44.

Similarly, Berger, “The Strashun Library in Vilna,” p. 517 claims that part of the Strashun Library went to YIVO and the other part to Hebrew University.

Similarly, the JNUL catalog does not list any items whose provenance extends to the Strashun Library. It is possible that YIVO and Berger confused the JNUL with the Jerusalem Central Library discussed below. Or simply conflated the Strashun Library with the numerous other European libraries that the JNUL successfully rescued.

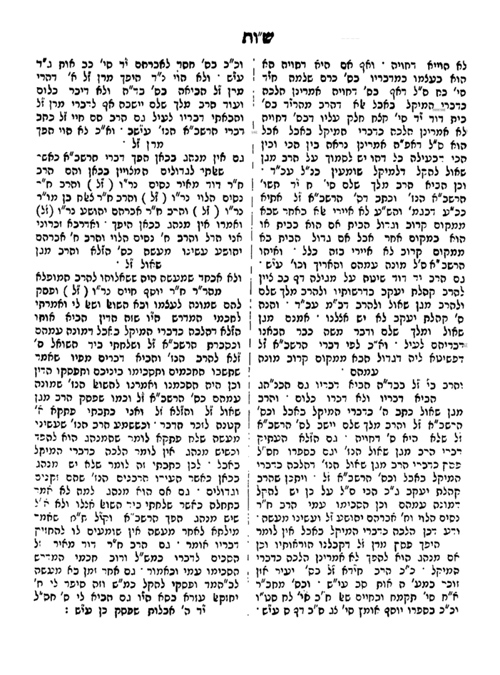

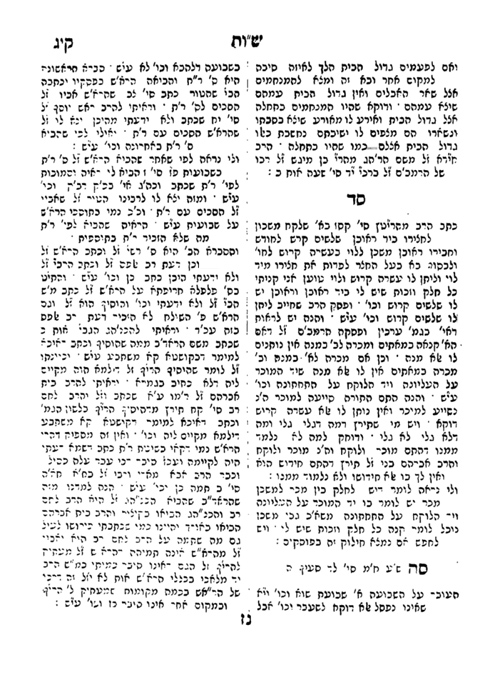

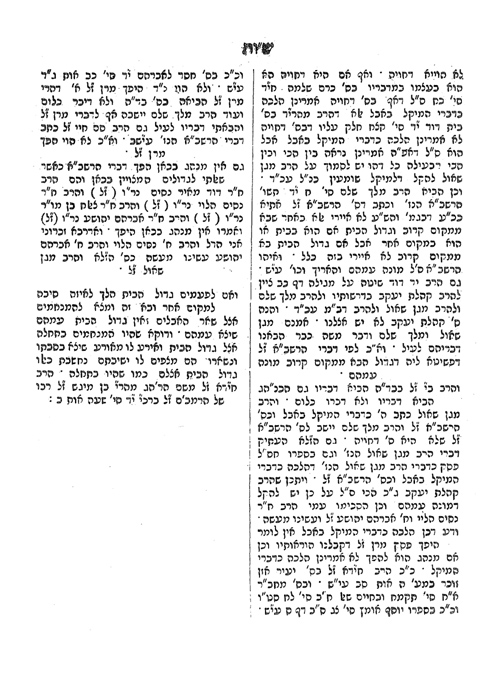

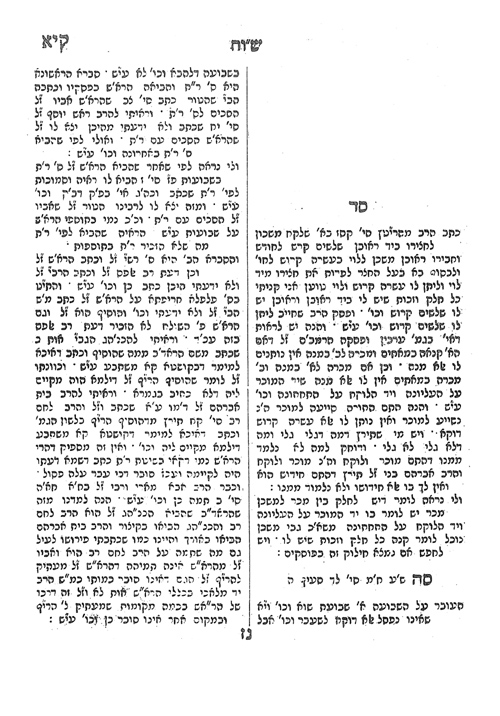

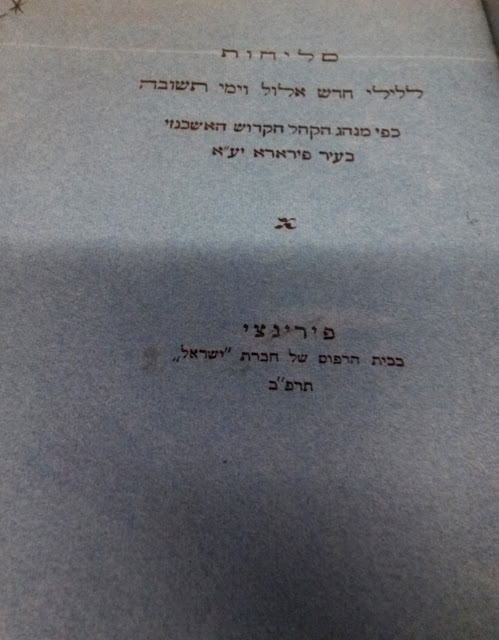

נוסח סליחות אשכנזי מודפס ארבע עשרה בלתי ידוע

דוד חיים רוט

נוסחאות מודפסים של סליחות אשכנזים: אשכנז הכללי (פפד’מ), עלזאס, פיורדא-נירנברג, וורמייזא,

פלאס, שוואבין-שוויץ, קוילן, אשכנזים שבאיטליה (כל הנ’ל הם שייכים לנוסח אשכנז

המערבי), ליטא, פולין, בהמן, פוזנא, ובית כנסת הישן בפראג (ששייכים למנהג המזרחי).[2],[3]

בכל יום, ובכל הנוסחאות הנ”ל, יש סדר שונה לכל יום של ימי אלול וימי התשובה,

וכן לשחרית, מוסף, ומנחה של יוהכ’פ.[4]

בספריה של בית מדרש לרבנים באמריקה, צריכים להבין קצת על מנהגי יהודי איטליה. באיטליה קיימות שלש ‘עדות’ שנוהגות מנהגים

שונים: אשכנזים (שנוהגים מנהג אשכנז המערבי), ספרדים, ובני רומא. כמו שהזכרנו לעיל, יש מנהג מיוחד לסליחות שנהוג

(או שהיה נהוג) אצל אשכנזים שבאיטליה (שהיה נהוג אף אצל האשכנזים שביון), אבל מה

שמצאתי הוא משהו שונה. ספר סליחות זה,

שנדפס בפירנצה ב-1922, הוא “סליחות ללילי אלול וימי תשובה כפי מנהג הקהל

הקדוש האשכנזי בעיר פירארא יע’א”. אף

שפירארא היא עיר באיטליה, נראה שבפירארא לא נהגו לומר סליחות לפי ‘מנהג האשכנזים

שבאיטליה’, אלא לפי מנהג מיוחד שלהם שמצאנו.

מנהג זה ייחודי אצל קהילות האשכנזים הנ”ל, שאין בו אלא סדר סליחות

אחד, ונראה שאמרוהו בכל יום, ודומה למנהג רוב הספרדים היום שאומרים אותם הסליחות

בכל יום[5]. לפי זה, סביר לומר שתופעה זו הגיעה מהשפעת

הספרדים שמתגוררים ליד קהילה זו באיטליה, אך גם ייתכן שמשום שמנהגי הסליחות לא

נקבעו עד די מאוחר[6]

התגבש בצורה שונה במקומות שונים. אי נמי,

אפשר להציע שאי פעם קהילת האשכנזים שבפירארא אמרו נוסח קבוע לסליחות שמחולק לפי

הימים (או לפי מנהג אשכנזים שבאיטליה או לפי נוסח אחר), ובדורות האחרונים החליטו

לקצר, ובזה מובן מה שלא מצאנו נוסח זה אלא בדפוס די מאוחר.

תפילה’, ואח’כ אומרים (כמובן עם י”ג מדות בין כל סליחה וסליחה) סליחות ‘אנשי

אמנה אבדו’,[8]

‘יום ישועה ועת רצון’,[9] ופזמון

‘ישראל נושע בה”,[10] ואח”כ

ממשיכים ‘זכור לנו ברית אבות’,[11] וידוי,

וכמה מהתחנונים שבסוף הסליחות,[12] ואחר כך

מופיע הוראה לומר קדיש תתקבל, ומשמע שלא נפלו על פניהם.

מנהג ליטא, עמ’ 7; הקדמה למחזור ליוהכ”פ, עמ’ יג.

מהם – אשכנז, עלזאס, פולין, ליטא, ובהמן – נהוגים עדיין היום. אינני יודע אם יש היום איזשהו קהילה שנוהגת

מנהג פיורדא-נירנברג, שוואבין-שוויץ, אשכנזים שבאיטליה, ובית כנסת הישן בפראג,

ואני מניח (לדאבוני) שאין שום קהילה בעולם שנוהגת לפי מנהג וורמייזא, פלאס, קוילן,

או פוזנא. אם יש לאף אחד מדע לגבי

הנוסחאות שאני מסתפק בהם, אני מעוניין מאוד לדעת על זה.

גיאוגרפיים, ואין שום קשר בין מתנגדים וחסידים, נוסח אשכנז וספרד, וכו’, שכן

חילוקים אלו קיימו כבר כמה מאות שנים קודם שהחסידים המציאו את ‘נוסח ספרד’.

היום עד חצי השני של המאה ה-19 (עי’ בהקדמה למחזור גולדשמידט יו”כ עמ’ יג). וכתב הטור (או”ח תרכ) ש”סליחות ורחמים

חובת היום הם”, והערוך השלחן (או”ח תרכ,א) צעק ככרוכיא על מנהג הטעות המחודש

שלא לומר סליחות, שאין לזה יסוד כלל וכלל.

הסליחות לפי הימים, ואף בימינו יש ספרדים בצפון אפריקה, או יוצאי צפון אפריקה, שעדיין

אומרים את הסליחות ע”פ ההחלוקה לימים שבספר שפתי רננות.

מהר”ז יענט (תחילת המאה ה-15), והוא זהה למנהג האשכנזים שבאיטליה (ומודפס (עם

שיבושים) במנהגי מהר”י טירנא של מכון ירושלים, עמ’ קעט ואילך), וכן יש כמה

כת”י לפי נוסח זה או נוסח קבוע אחר. אבל מ”מ בהרבה קהילות עדיין לא נתקבלו

סדרים כאלה עד תקופת הדפוס, וקודם לכן כל חזן אמר את מבחר הסליחות שבחר

בהם, עיין בזה מאמרם של יונה ואברהם פרנקל על מחזור נירנברג here)), ויש לציין שבמחזור נירנברג עצמו יש סדר קבוע לסליחות של ער”ה,

צום גדליה, עיו”כ, ולתפילות יו”כ.

(תודתי לר’ אברהם לוין שעזר עם המדע על כתבי היד.)

הצדקה’, ואין אומרים אשרי או אדון עולם קודם.

משאר הימים, ויש שאומרים אותו אף באחד מימי בה”ב.

אחרות, אבל לא ייתכן שחסר כאן משהו, שהרי כתוב בתחילה ‘א-להנו וא-להי אבותינו’,

ועוד שיש מספרי עמודים, ולא חסר כאן כלום.

כמה מנהגים באחד מימי בה”ב.

‘סרנו ממצותיך’ ו’הרשענו ופשענו’, מופיע ‘ואתה רחום מקבל שבים ועל התשובה מראש הבטחתנו

ועל התשובה עינינו מיחלות לך: עשה למענך אם לא למענינו עשה למענך והושיענו’ [וחסר

כל הפס’ מנביאים וכתובים, כגון עזרא הסופר אמר לפניך], וקטע עננו ה’ עננו הוא גם

כן קטוע.

A Note Regarding Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer’s Position on Opening a Refrigerator on Shabbat

Lo hayu dvarim me-olam. Rav Simcha Zelig did not permit opening a refrigerator when the light inside will go on. Rav Simcha Zelig wrote (Hapardes 1934, num. 3, page 6) that it is permitted to open the refrigerator since the intention is to remove an item, “v’aino mechavein lehadlik et ha-elektri.”[2] The authors misinterpreted this statement to be a reference to an electric light in the refrigerator.

I would add two endnotes – when surveying Halachot with significant practical implications, such as in the realm of Hilchot Shabbat, it is an author’s responsibility to ensure that all sources are cited accurately, lest a reader rely on an incorrect citation with the result of Chillul Shabbat. Secondly, when confronted with a Halachic position of a Gadol B’Yisrael that seems to be entirely erroneous, the possibility that the Gadol’s position is being misunderstood must be explored.

Simcha Zelig was in possession of Hapardes 1931 number 2 when he wrote this

letter. He certainly had 1931 number 3, as obvious from his citation of R’

Moshe Levin on the permissibility of making ice on Shabbat, which appears in

number 3. It is likely that Rav Moshe Soloveitchik sent him 1931 number 3

because it contains a presentation of a shiur that Rav Moshe delivered in the

name of his son, Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, and Rav Moshe no doubt wished to

share his son’s chiddushim with Rav

Simcha Zelig. 1931 number 2 also contains a presentation of a shiur that Rav

Moshe delivered in the name of his son, so it is likely that 1931 number 2 was

also one of the three editions of Hapardes that Rav Simcha Zelig received from

Rav Moshe.

motor would be considered a psik reisha

d’lo nicha lei, see Minchat Shlomo (Kama) 10, as well as Minchat Yitzchak

2:16. Rav Eliezer Waldenberg seems to accept this classification of triggering

the motor as a psik reisha d’lo nicha lei,

in Tzitz Eliezer 8:12.