Finders Keepers? The Itinerant History of Strashun Library of Vilna, Pt I

Finders Keepers? The Itinerant

History of Strashun Library of Vilna

by Dan Rabinowitz

History of Strashun Library of Vilna

by Dan Rabinowitz

Since the 1990s, the issue of reparation of items looted by the Nazis has become a high-profile issue, with numerous successful attempts at reuniting owners with their stolen possessions. The recent movie, Monuments Men, fictionalized the

Allies’ post-war efforts that led to the locating some of these looted treasures. While some of the best-known examples of these recovered treasures are related to art, gold, or Swiss bank accounts, Hebrew books were also part of the Nazi’s appropriation scheme and were included in the items recovered after World War II. Some of the books recovered belonged to a unique institution, the first Jewish public library, and tracing the journey of these books, up to present day, parallels that of its patrons, tortured, uncertain, and yet despite all odds, surviving.

Allies’ post-war efforts that led to the locating some of these looted treasures. While some of the best-known examples of these recovered treasures are related to art, gold, or Swiss bank accounts, Hebrew books were also part of the Nazi’s appropriation scheme and were included in the items recovered after World War II. Some of the books recovered belonged to a unique institution, the first Jewish public library, and tracing the journey of these books, up to present day, parallels that of its patrons, tortured, uncertain, and yet despite all odds, surviving.

Matisyahu Strashun the Library’s Architect and Founder

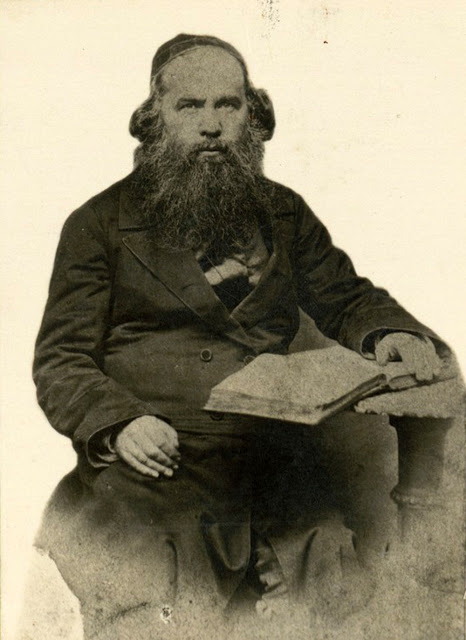

Matisyahu Strashun[1] was born in 1817 in Vilna. His family was among the Vilna elite. His father, Samuel Strashun (also known as Rashash), whose notes/annotations – he never published a stand-alone work – to numerous classic rabbinic works, including Midrash Raba, Mishna, and Maimonides’ Mishna Torah, and Talmud Bavli.[2] In terms of breadth, the latter is most

impressive, as his notes cover nearly every single page[3] of the Talmud Bavli.[4]

impressive, as his notes cover nearly every single page[3] of the Talmud Bavli.[4]

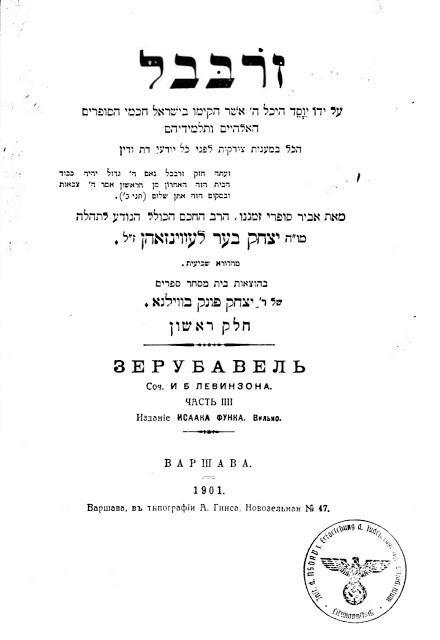

Matisyahu too was a Talmudist, his comments to Baba Batra and Eruvin are incorporated into the Vilna edition of Talmud Bavli, and was proficient in the entire corpus of rabbinic literature.[5] Matisyahu espoused views that were consistent with the haskalah movement.[6] For example, Matisyahu supported Max Lilienthal’s controversial attempt to reform “the Jewish educational system within the Pale Settlement,”[7] and Matisyahu help found and financially supported two schools in Vilna aligned with the haskalah.[8] Matisyahu corresponded with leaders of the haskalah movement, Isaac Ber Levinsohn, among others, and Strashun’s articles appeared in both rabbinic as well as haskalah newspapers and journals.[9] And, his home was a salon of sorts for traditionalists and the maskilim of Vilna.[10]

Strashun was independently wealthy and derived his substantial income from commercial and banking activities rather than rabbinic activities. Yet he was considered a leader of the Vilna community. He served on a number of communal institutions including the Vilna Tzedakah Gedolah. And, at his death, he donated over 50,000 rubles to charity (approximately $1 million today). Leading Eastern European rabbis, R. Yitzhak Elchonon Spector and R. Jacob Joseph (later Chief Rabbi of

New York) among them, eulogized Strashun.[11] Posthumously, a street in Vilna was named after him.[12]

New York) among them, eulogized Strashun.[11] Posthumously, a street in Vilna was named after him.[12]

Throughout his life, he was an avid book collector, and, at the time of his death, amassed a collection of over 5,700 books and manuscripts.[13] His collection included incunabula, rare and controversial works (e.g. Me’or Eynaim), and manuscripts – from his father in addition to other authors. As reflected in his outlook during his lifetime, Strashun’s collection included rabbinic and haskalah works and books in non-Hebrew languages.[14]

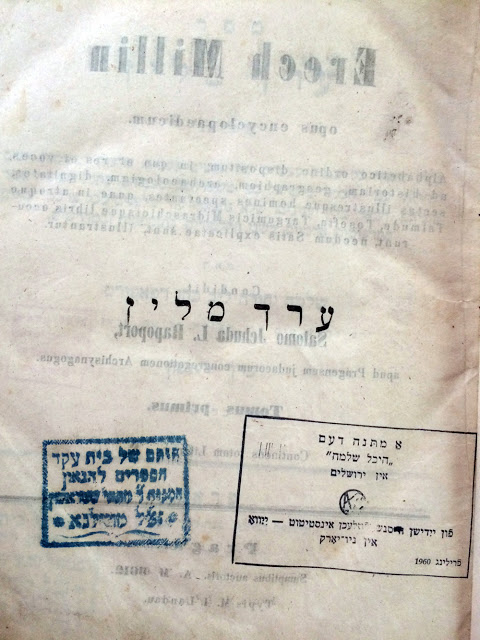

During Strashun’s lifetime, numerous printing houses and bookstores populated Vilna, providing access to most contemporary books, including in languages other than Hebrew.[15] But, unfortunately, we do not have much information regarding how and when Strashun amassed his collection that extended well beyond those contemporary books, beyond that when he traveled he took the opportunity to seek out and purchase books. For example, when he took therapeutic trips to the spa he also took that opportunity to seek out and purchasing books. In addition to Strashun’s spa trips, in 1857 he went on a Rabbinic tour of Eastern Europe and visited R. Shlomo Yehuda Rappaport (Shi”r) in Prague and R. Tzvi Hirsch Chajes.[16] But, R. Rapahel Nathan Rabinowicz, a book dealer and noted book collector, commented after visiting Strashun that while Strashun’s collection was larger than Rabinowicz’s, his collection was richer in rare and older books.[17]

STRASHUN’S COPY OF SHIR’S EREKH MILIM

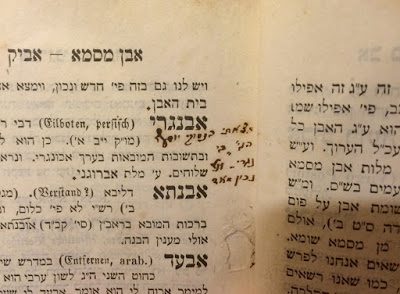

STRASHUN MARGINALIA TO EREKH MILIM

Creation of the Vilna Jewish Public Library

At his death in 1885, Strashun left no direct heirs. He did, however, provide for the disposition of his library in his will. In the past, those with large libraries had sold or left it to relatives,[18] Strashun elected a novel approach, rather than an individual or individuals he bequeathed his library to the Vilna Jewish community writ large, with instructions to establish a stand-alone public library.[19] His vision for the library was modeled on “the non-Jewish libraries that he saw [20] in the Diaspora.”[21] To that end, Strashun provided not only the books but also the funds to support the creation and sustainment of the library.[22] Immediately the impact of this decision was apparent. At his funeral, among other enumerated good deeds and scholarship mentioned was, “the large library he left after death for the benefit of the community,” and which will “provide a

lasting legacy beyond that of any actual blood descendants.”[23]

lasting legacy beyond that of any actual blood descendants.”[23]

The creation of a public library out of Strashun’s personal collection was not a swift one, for seven years following Strashun’s death “the books remained under

lock and key” and were available only to those with special access.[24] It remained in this state even though there were trustees and enough money to cover its operations.[25] Although the

library did not open to the public, the trustees were not idle during this time; and in 1889, published a complete catalog of Strashun’s collection. His collection was comprised of 5,753 items, 63 of which contained marginalia in his hand.[26]

lock and key” and were available only to those with special access.[24] It remained in this state even though there were trustees and enough money to cover its operations.[25] Although the

library did not open to the public, the trustees were not idle during this time; and in 1889, published a complete catalog of Strashun’s collection. His collection was comprised of 5,753 items, 63 of which contained marginalia in his hand.[26]

The Library is Open to the Public

In 1892, the Library was finally opened to the public. At the time, however, it remained in Strashun’s home.[27] For years

after the library was opened to the public, in legal documents, the listed owner was not the Vilna community but one of the Library’s trustees. Although Strashun’s intent was clear – that the Library belonged to the community and not a trustee or any other individual – the Library’s legal status clouded that directive. In the late 1890s, there was a successful campaign to correct that issue, and the community becomes the sole owner of the Library, fulfilling Strashun’s wishes regarding ownership.[28]

after the library was opened to the public, in legal documents, the listed owner was not the Vilna community but one of the Library’s trustees. Although Strashun’s intent was clear – that the Library belonged to the community and not a trustee or any other individual – the Library’s legal status clouded that directive. In the late 1890s, there was a successful campaign to correct that issue, and the community becomes the sole owner of the Library, fulfilling Strashun’s wishes regarding ownership.[28]

The Library & Its Impact on the Vilna Community

In 1902, the Library finally moved into a building of its own in the courtyard of the Great Synagogue of Vilna.[29] From this

point forward, the Strashun Library would be one of Vilna’s most important institutions.

point forward, the Strashun Library would be one of Vilna’s most important institutions.

The Strashun Library was a Jewish public institution and, to fulfill the needs of the public, additional steps were required beyond building and maintaining

infrastructure and clarifying ownership.

Specifically, although Strashun’s collection was substantial both in

terms of size and breadth, it was still the product of one man’s idea of a library. For this reason, Hillel Noach Steinschneider, one of Vilna’s leading scholars and historians, pleaded with the public to donate books and ensure the completeness of the library and fulfill its mission of serving the entire community. He acknowledged that Strashun amassed a very impressive private collection, but that for a public library his collection alone was insufficient because “it is lacking in books for people” whose interests did not align with Strashun’s.

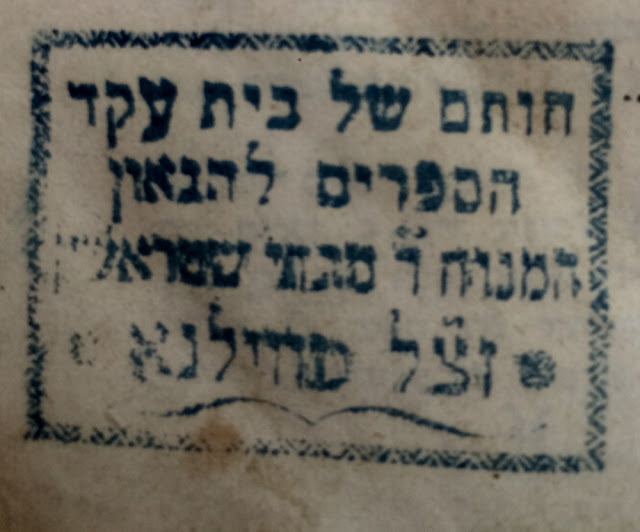

That is, a public library is not only a place open for all but also one that provides value for all. Consequently, the library’s composition must reflect the entirety of its audience and not a single collector. Apparently, this plea was successful,[30] many Vilna scholars donated their collections to the Library in addition to the general public, and, by the 1930s, the Library had grown to over 35,000 volumes.[31] Additionally, Vilna’s Tzedakah Gedolah organization also provided funds for acquisitions. Books acquired through those funds contain a special stamp or receipt.

infrastructure and clarifying ownership.

Specifically, although Strashun’s collection was substantial both in

terms of size and breadth, it was still the product of one man’s idea of a library. For this reason, Hillel Noach Steinschneider, one of Vilna’s leading scholars and historians, pleaded with the public to donate books and ensure the completeness of the library and fulfill its mission of serving the entire community. He acknowledged that Strashun amassed a very impressive private collection, but that for a public library his collection alone was insufficient because “it is lacking in books for people” whose interests did not align with Strashun’s.

That is, a public library is not only a place open for all but also one that provides value for all. Consequently, the library’s composition must reflect the entirety of its audience and not a single collector. Apparently, this plea was successful,[30] many Vilna scholars donated their collections to the Library in addition to the general public, and, by the 1930s, the Library had grown to over 35,000 volumes.[31] Additionally, Vilna’s Tzedakah Gedolah organization also provided funds for acquisitions. Books acquired through those funds contain a special stamp or receipt.

The Library was open seven days a week and became the central meeting location for the residents of Vilna.[32] The Library’s visitors were representative of Strashun’s commitment to both traditional and modern ideas and ideals. Patrons included “rabbis and talmudic scholars who were studying responsa and Halakhic

works” and who sat side-by-side with the “younger generation who were reading haskalah works.”[33] When dignitaries came to Vilna, the Strashun library

was a waypoint.[34]

works” and who sat side-by-side with the “younger generation who were reading haskalah works.”[33] When dignitaries came to Vilna, the Strashun library

was a waypoint.[34]

The intent was to have Herzl be the first visitor to the Library, however, the Russian government prohibited him appearing at the Library.[35] Other famous Jewish personalities did visit and signed the guest book, known as the Golden Book, including Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh (Mendele Mokher Seforim), and Hayim Nachum Bialik, in addition to more traditionalists, R. David Friedman of Karlin, R. Shlomo Ha-kohen, and the Chafetz Chayim.[36] The Library was not only known for its visiting

Jewish celebrities, but also for its well-regarded holdings. According to A.J. Heschel, it was the largest public Hebraic library in Eastern Europe reported holding over 40,000 volumes.[37] On the one hand, the Strashun library was recognized as one of the greatest cultural institutions in Eastern Europe, on the other, like so many public institutions, the Library struggled to raise sufficient funds throughout the early part of the 20th century, consistently hampering its ability to maintain and build its

collections in addition to limiting its public access.[38] But, it would not be funding that led to its demise but the Nazis and their campaign to appropriate Jewish cultural treasures.

Jewish celebrities, but also for its well-regarded holdings. According to A.J. Heschel, it was the largest public Hebraic library in Eastern Europe reported holding over 40,000 volumes.[37] On the one hand, the Strashun library was recognized as one of the greatest cultural institutions in Eastern Europe, on the other, like so many public institutions, the Library struggled to raise sufficient funds throughout the early part of the 20th century, consistently hampering its ability to maintain and build its

collections in addition to limiting its public access.[38] But, it would not be funding that led to its demise but the Nazis and their campaign to appropriate Jewish cultural treasures.

The Nazi’s Looting of the Strashun Library

During World War II, Vilna was occupied and controlled first by the Soviets, then the Lithuanian government, the Soviets again, and finally by the Germans.[39] While under Lithuanian and Soviet rule, the Library had its share of challenges, but none

of those compared to the Nazi’s systematic campaign to identify, collect, and appropriate important Jewish treasures –specifically books – and, consequently, important libraries. The intent was that these pillaged libraries would supplement the already substantial Judaic holdings of Frankfort City Library.[40] Immediately after the Nazis occupied Vilna, the Strashun Library as Vilna’s “oldest and perhaps most distinguished” library was identified as a target for this campaign.[41]

of those compared to the Nazi’s systematic campaign to identify, collect, and appropriate important Jewish treasures –specifically books – and, consequently, important libraries. The intent was that these pillaged libraries would supplement the already substantial Judaic holdings of Frankfort City Library.[40] Immediately after the Nazis occupied Vilna, the Strashun Library as Vilna’s “oldest and perhaps most distinguished” library was identified as a target for this campaign.[41]

Less than a month after occupying Vilna, the Nazis “enlisted” the Library’s librarian, Chakil Lunski, who had served in that capacity for over forty years, in addition to others, to select, identify and catalog important books including “the incunabula and manuscripts in the Strashun Library” to be sent back to Germany.[42] Needless to say, Lunski was “distraught” that “he [was] supposed to help remove the treasures from ‘his’ Strashun Library that he protected for 45 years!”[43] Consequently, a number of books from the Strashun Library ended up in Frankfort, Germany.[44]

Post War Efforts to Reclaim Heirless Jewish Property

The Library’s building did not survive the war, but some of its books did.[45] After WWII, the Allies recovered thousands of items the German’s looted and collected them at the Offenbach Depot outside of Frankfort.[46] Much of what was recovered was likely heirless and the Allies faced with the dilemma of restitution. Initially, the Americans took the position that heirless property should return to the country from which it was looted.[47] This position raised the specter of rare and important Judaica and Hebraica returning to Poland or even Germany. This outcome was unacceptable to many Jews.[48] Some elected to influence the fate of looted heirless books through traditional democratic means, others took matters into their own hands.[49]

Free For All? The Disposition of Other Significant European Libraries

The Strashun Library was by no means the only library identified at the Offenbach depot. There were numerous other

libraries, both public and private that ended up at Offenbach, without any clear method of repatriation. This lack of clarity leads to inconsistent results at best. Indeed, first-hand accounts of post-war Germany confirm the ad-hoc, doubtful legal grounds and sometimes completely lawless reparation regime in the post-war chaos. In many instances, individuals made many of the decisions regarding disposition with little information and virtually to no oversight.

libraries, both public and private that ended up at Offenbach, without any clear method of repatriation. This lack of clarity leads to inconsistent results at best. Indeed, first-hand accounts of post-war Germany confirm the ad-hoc, doubtful legal grounds and sometimes completely lawless reparation regime in the post-war chaos. In many instances, individuals made many of the decisions regarding disposition with little information and virtually to no oversight.

For example, Solomon B. Freehof, who himself amassed one of the greatest responsa collections in the 20th century, spent time in post-war Germany and encountered heirless property and describes attempts of repatriation. He indicates that

half of the heirless Jewish books recovered by the Allies went to the Jewish National and University Library (“JNUL”) at the Hebrew University (now the National Library of Israel),[50] which was “quite right” because some unnamed person or entity had determined “that clearly the [JNUL] should take the place of the vanished Jewish communities of Europe.”[51]

half of the heirless Jewish books recovered by the Allies went to the Jewish National and University Library (“JNUL”) at the Hebrew University (now the National Library of Israel),[50] which was “quite right” because some unnamed person or entity had determined “that clearly the [JNUL] should take the place of the vanished Jewish communities of Europe.”[51]

Others agreed with Freehof that the natural repository for heirless books of European origin was the JNUL in Jerusalem. Most notably, Judah Magnes, and the trustees of the JNUL wanted to recover and claim for the JNUL as much heirless Judaica as possible. The JNUL dispatched Gershom Scholem, the eminent Kabbalah scholar, and bibliophile, to Europe to locate and return heirless property. He discovered a significant number of important books and manuscripts in the Offenbach Depot

and did everything in his power, including employing very underhanded means, to repatriate items to Hebrew University.[52]

and did everything in his power, including employing very underhanded means, to repatriate items to Hebrew University.[52]

Initially, Scholem had a very difficult time securing authorization to even enter Germany and the Offenbach Depot.[53] When he was eventually granted permission to view the contents of the Depot, it was with the explicit condition that he

could not remove any items. But, for Scholem, some items proved too enticing. Scholem identified a number of rare and important books and manuscripts. He was concerned that if the disposition of these items were left to the Allied authorities the items would not end up in Jerusalem, but, instead, at the Jewish Theological Seminary, or some other institution, in the United States. This was unacceptable to Scholem. To facilitate the transfer of these items to the JNUL, Scholem colluded with a Jewish American serviceman to smuggle the works out of Offenbach. Scholem placed the collection into five boxes but did not label

their contents and provided a fake name on the invoice. The American serviceman personally ensured that the boxes were shipped to Paris, after which they were sent to the JNUL. Eventually, the Allies found out about the theft, and demanded the return of the five boxes, even lodging a formal diplomatic complaint. In the end, after much back and forth, the boxes remained at the JNUL.[54]

could not remove any items. But, for Scholem, some items proved too enticing. Scholem identified a number of rare and important books and manuscripts. He was concerned that if the disposition of these items were left to the Allied authorities the items would not end up in Jerusalem, but, instead, at the Jewish Theological Seminary, or some other institution, in the United States. This was unacceptable to Scholem. To facilitate the transfer of these items to the JNUL, Scholem colluded with a Jewish American serviceman to smuggle the works out of Offenbach. Scholem placed the collection into five boxes but did not label

their contents and provided a fake name on the invoice. The American serviceman personally ensured that the boxes were shipped to Paris, after which they were sent to the JNUL. Eventually, the Allies found out about the theft, and demanded the return of the five boxes, even lodging a formal diplomatic complaint. In the end, after much back and forth, the boxes remained at the JNUL.[54]

As germane here, eventually, the boxes’ content were cataloged and it was determined that a third of the works were not heirless – their ownership was clear and restitution was possible.[55] Nevertheless, the content of the five boxes were incorporated into the JNUL.

Another example of unilateral ostensive benevolent restitution occurred with the “library of the prestigious Klaus synagogue of Mannheim, [that] ended up with U.S. Army Chaplin, Rabbi Henry Tavel.” Who, “on his own authority . . . shipped it to his alma mater, the Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati.”[56]

The Lost & Found: The Strashun Library Post-WWII

The determination regarding the disposition of the Strashun library after the Holocaust was no different from other heirless property, ad hoc and questionable. Lucy Dawidowicz, worked for YIVO before WWII and spent time in Vilna.

After WWII, on behalf of the Jewish Distribution Committee after World War II, she went to the Offenbach Depot to assist with identification of heirless books. Prior to coming to Offenbach, she had “promised [herself] that [she] would do [her] best to

safeguard the rights of possible owners and heirs.”[57] And, when she came upon some of the remains of the YIVO collection,[58] she “was in a state of exaltation” and in a letter home wrote that she “had ‘a feeling akin to holiness, that [she] was touching something sacred.’”[59]

After WWII, on behalf of the Jewish Distribution Committee after World War II, she went to the Offenbach Depot to assist with identification of heirless books. Prior to coming to Offenbach, she had “promised [herself] that [she] would do [her] best to

safeguard the rights of possible owners and heirs.”[57] And, when she came upon some of the remains of the YIVO collection,[58] she “was in a state of exaltation” and in a letter home wrote that she “had ‘a feeling akin to holiness, that [she] was touching something sacred.’”[59]

Dawidowicz also came upon books that she “could identify came from the Strashun Library.” Whereupon she recalled “a

strange story” that the head of YIVO, Max Weinreich,[60] had told her “back in 1940.” Weinreich told her that during the brief period of time when the Soviets had returned Vilna to Lithuanian control, YIVO attempted to move its library out of Vilna.[61] And, that “the trustees of the Strashun Library, also fearing for the sake of their library, asked the Vilna YIVO to ship [the Strashun Library] too.” Unfortunately, the shipment never occurred and both libraries remained in Vilna and ultimately plundered by the Nazis.

strange story” that the head of YIVO, Max Weinreich,[60] had told her “back in 1940.” Weinreich told her that during the brief period of time when the Soviets had returned Vilna to Lithuanian control, YIVO attempted to move its library out of Vilna.[61] And, that “the trustees of the Strashun Library, also fearing for the sake of their library, asked the Vilna YIVO to ship [the Strashun Library] too.” Unfortunately, the shipment never occurred and both libraries remained in Vilna and ultimately plundered by the Nazis.

While the shipment never occurred, in Dawidowicz’s telling the attempted shipment was an irrevocable act with significant implications regarding the Library’s ownership. She inferred that the Strashun trustees request to join the YIVO shipment also implicitly ceded ownership of the Strashun Library to YIVO. Thus, there she had no doubt regarding the proper disposition of the Strashun Library. Based entirely upon the “strange story” she heard, and even though according to her retelling the Strashun trustees had only intended YIVO to act as a shipper,[62] Dawidowicz told the Director of the Offenbach Depot that the heirless “remains of the Strashun Library ought to be considered as YIVO property.” She appealed to the Allied authorities and her position carried the day and the remnants of Strashun Library went to YIVO in New York.[63]

In a recent exhibit devoted to YIVO’s Strashun collection, the issue of the Strashun Library’s provenance is not discussed in any detail. Instead, the book accompanying the exhibit simply states that all the remnants of the Strashun Library “were

rescued from the ruins of Europe and brought back to YIVO in New York in 1947.”[64] YIVO’s library catalog again implies that all the recovered books went to YIVO and links the disposition of the Strashun Library with that of YIVO’s, the provenance note explains that “[t]he Strashun Collection, along with the YIVO Vilna collections, were liberated by the American Army, and

re-repatriated to YIVO in New York in April 1947.”[65]

rescued from the ruins of Europe and brought back to YIVO in New York in 1947.”[64] YIVO’s library catalog again implies that all the recovered books went to YIVO and links the disposition of the Strashun Library with that of YIVO’s, the provenance note explains that “[t]he Strashun Collection, along with the YIVO Vilna collections, were liberated by the American Army, and

re-repatriated to YIVO in New York in April 1947.”[65]

In reality, not all the remaining Strashun books went to YIVO, nor did everyone agree with the determination that YIVO was the rightful heir of the Strashun Library.

To be continued in Pt. II…

[1] For biographical information and sources see Tzvi Harkavy, Le-Heker Misphahot, (Jerusalem: Hotsa’at ha-Sefarim ha-Erets-Yisre’elit, 1953), 47-48 and n.79.

[2] A complete bibliography of his works, both published and unpublished, appears in Tzvi Harkavy, Le-Heker Misphahot, (Jerusalem: Hotsa’at ha-Sefarim ha-Erets-Yisre’elit, 1953), 45-46. Rashash’s comments on Rambam were printed in

Mekorei Rambam, first published in 1870 in Vilna, and while not a true stand-alone work, Rashash’s comments appear

alone, without the Rambam’s text. See Mekorei ha-Rambam, Harkavy ed., (Jerusalem, Hatsa’at ha-Sefarim ha-Erets-Yisre’elit, 1957, Im ha-Madurah, and p. 59.

Mekorei Rambam, first published in 1870 in Vilna, and while not a true stand-alone work, Rashash’s comments appear

alone, without the Rambam’s text. See Mekorei ha-Rambam, Harkavy ed., (Jerusalem, Hatsa’at ha-Sefarim ha-Erets-Yisre’elit, 1957, Im ha-Madurah, and p. 59.

[3] For a list of the handful of pages he omitted, see Rafael Katzenellenbogen, Rash”sh le-Shitato, in Mekori Ha-Rambam Le-Rash”sh, ed. Harkavy, (Jerusalem, 1957), 64.

[4] For general biographical details on the Strashun family, see Frida Shor, From “Likute Shoshanim” to “The Paper Brigade” The Story of the Strashun Library in Vilna, (Tel Aviv: Ariel, 2012), 15-28, and the sources cited therein. See also Shua Engelman, “Rabbi Samuel Strashun and his Haggahot on the Babylonian Talmud,” (PhD dissertation, Bar-Ilan University, 2009; Hebrew); regarding Samuel’s Talmudic annotations as compared to others, see Yaakov Shmuel Spiegel, Chapters in the History of the Jewish Book, Scholars & their Annotations (Ramat-Gan: Bar Ilan University, 2005), 421-22. Cf. Mordechai Zalkin, “Samuel and Mattiyahu Strashun: Between Tradition and Innovation,” in Mattiyahu Strashun, 1817-1885: Scholar, Leader, and Book Collector, (New York: YIVO Institute, 2001), 6-7.

[5] Moshe Shimon Anktokolski, Evel Kaved, infra n.12, 23.

[6] Mordechai Zalkin, “Samuel and Mattityahu Strashun: Between Tradition and Innovation,” in Yermiyahu Aharon Taub, ed., Mattityahu Strashun, 1817–1885: Scholar, Leader, and Book Collector (New York: YIVO Institute, 2001), 1-27. Samuel has made a very small number of comments that can be read to be consistent with ideas of the haskalah, but these do not approach Matisyahu’s active involvement with the movement, including his very public support of the movement. Additionally, it is unclear if Samuel’s comments are simply limited to their specific context.

Indeed, the examples Zalkin provides regarding Samuel’s alignment with haskalah do not support Zalkin’s thesis. Id. at 25

n.10. First, Zalkin, cites Strashun’s comment in Gitten 6b, that “we find many amora’im who did not know how to read scripture” as proof of his “unorthodox” views. But we find a similar statement from the medieval period. See Tosefot, Bava Batra, 113a. Zalkin’s second citation is to Rashas’s comments, Rosh ha-Shana 26a, “certain things that were uttered in a particular time and particular place are inserted by editors of the Talmud in their appropriate location in the text.” This misrepresents the Rashash. Rashash is attempting to answer how the Talmudic sage, Levi, was unaware of an explicit verse as the TB in RH 26a implies. Rashash explains that although there is no explicit mention of the time or place that this story occurred, Rashash posits that the story in Rosh Hashana occurred at the same time as another story with Levi, Yevamot 105a, where he had a moment of senility.

Rashash is not offering his opinion regarding the redaction of the Talmud, instead he is merely dating the story in Rosh ha-Shana. Finally, it is unclear the relevance of Zalkin’s third example, “you will find many contradictions between different locations is (sic) Rashi’s text.” Locating and alleging contradictions in Rashi is hardly remarkable.

n.10. First, Zalkin, cites Strashun’s comment in Gitten 6b, that “we find many amora’im who did not know how to read scripture” as proof of his “unorthodox” views. But we find a similar statement from the medieval period. See Tosefot, Bava Batra, 113a. Zalkin’s second citation is to Rashas’s comments, Rosh ha-Shana 26a, “certain things that were uttered in a particular time and particular place are inserted by editors of the Talmud in their appropriate location in the text.” This misrepresents the Rashash. Rashash is attempting to answer how the Talmudic sage, Levi, was unaware of an explicit verse as the TB in RH 26a implies. Rashash explains that although there is no explicit mention of the time or place that this story occurred, Rashash posits that the story in Rosh Hashana occurred at the same time as another story with Levi, Yevamot 105a, where he had a moment of senility.

Rashash is not offering his opinion regarding the redaction of the Talmud, instead he is merely dating the story in Rosh ha-Shana. Finally, it is unclear the relevance of Zalkin’s third example, “you will find many contradictions between different locations is (sic) Rashi’s text.” Locating and alleging contradictions in Rashi is hardly remarkable.

[7] Zalkin, id., at 15.

[8] Shalom Pludermacher, Zikaron le-Hakham: Zeh Sefer Tolodot ha-Rav ha-Go’an, he-Hakham ha-Kollel Rabbi Matitayahu

Strashun Z’L, in Mattiyahu Strashun, Matat-Ya, Haghot, Hidushim ve-He’arot Me’irot ‘al Midrash Raba Pri Eito Shel Matityahu Strahsun, (Vilna: The Widow and Brothers Romm, 1893), 15.

Strashun Z’L, in Mattiyahu Strashun, Matat-Ya, Haghot, Hidushim ve-He’arot Me’irot ‘al Midrash Raba Pri Eito Shel Matityahu Strahsun, (Vilna: The Widow and Brothers Romm, 1893), 15.

[9] A partial bibliography of Strashun’s articles appears in his Sefer Matat Yah (Vilna, 1893), 41-74 (Hebrew), available online here. Reading, and certainly actively participating with, haskalah related newspapers was considered inconsistent with Ultra-Orthodox values and was grounds for expulsion from Volozhin Yeshiva. Shaul Stampfer, The Lithuanian Yeshiva, Revised & Expanded Edition, (Jerusalem: The Zalman Shazar Center for Jewish History, 2005), 176.

[10] Aviva Astrinsky, “A Brief History of the Strashun Library,” in Yermiyahu Aharon Taub, ed., Mattityahu Strashun, 1817–1885: Scholar, Leader, and Book Collector (New York: YIVO Institute, 2001), i.

[11] Duberosh ben Aleksander Torsh, Me’arat ha-Makhpelah, shnei Hepadim . . ., (Warsaw, 1887), 50.

[12] Moshe Shimon Antokolski, Evel Kaved, (Vilna: be-Defus Avhram Tzvi Katzenellenbogen, 1886), 8; Tzvi Harkavy, Le-Heker Misphahot, supra n.1, 47. During his lifetime he also donated to public institutions, among them, the yeshivot of Mir and Volozhin. Id. at 24.

[13] Moshe Shimon Antokolski, Evel Kaved, supra n.12, 11.

[14] Mordechai Zalkin, supra n.6, 17-8.

[15] Hagit Cohen, At the Bookseller’s Shop, The Jewish Book Trade in Eastern Europe at the End of the Nineteenth Century,

(Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press, 2006), 48-52.

(Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magnes Press, 2006), 48-52.

[16] Shalom Pludermacher, Zikaron le-Hakham, 1893), 17. His meetings are reflected in Strashun’s ownership of their works.

See Likutei Shoshaim, nos. 386,1024,1178, 2522, 3352, 3650, 3781, 4377, 5399, 5592. Regarding other well-known Hebrew book collectors and their collections, see Alexander Marx, “Some Jewish Book Collectors,” in his Studies in Jewish History & Booklore, (New York, 1941), 198-237; Cecil Roth, “Famous Jewish Book Collections & Collectors,” in Essays in Jewish Booklore, (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1971)330-35.

See Likutei Shoshaim, nos. 386,1024,1178, 2522, 3352, 3650, 3781, 4377, 5399, 5592. Regarding other well-known Hebrew book collectors and their collections, see Alexander Marx, “Some Jewish Book Collectors,” in his Studies in Jewish History & Booklore, (New York, 1941), 198-237; Cecil Roth, “Famous Jewish Book Collections & Collectors,” in Essays in Jewish Booklore, (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1971)330-35.

[17] “A Collection of Letter from Jewish Scholars to ShZH”H,” in Yad ve-Shem, reprinted in Yeshurun.

[18] David Oppenheimer’s library was the first library that was posthumously sold intact – to the Bodleian Library. See

Alexander Marx, “Some Notes on the History of David Oppenheimer’s Library,” Revue des Études Juives 82 [=Israel Lévi

Festschrift] (1926): 451-460; Charles Duschinsky, “Rabbi David Oppenheimer: Glimpses of His Life and Activity, Derived from His Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library,” Jewish Quarterly Review 20:3 (January 1930): 217-247; Alexander Marx, “The History of David Oppenheimer’s Library,” in Studies in Jewish History and Booklore (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1944), 238-255; and more recently in Joshua Teplitsky, “Between Court Jew and Jewish Court: David Oppenheim, The Prague Rabbinate, and Eighteenth-Century Jewish Political Culture (PhD dissertation, New York University, 2012); and Abraham Schischa, “Rabbinic Writings from the Collection of Rabbi David Oppenheim,” Yeshurun 31 (2014): 781-794 (Hebrew).

Alexander Marx, “Some Notes on the History of David Oppenheimer’s Library,” Revue des Études Juives 82 [=Israel Lévi

Festschrift] (1926): 451-460; Charles Duschinsky, “Rabbi David Oppenheimer: Glimpses of His Life and Activity, Derived from His Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library,” Jewish Quarterly Review 20:3 (January 1930): 217-247; Alexander Marx, “The History of David Oppenheimer’s Library,” in Studies in Jewish History and Booklore (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1944), 238-255; and more recently in Joshua Teplitsky, “Between Court Jew and Jewish Court: David Oppenheim, The Prague Rabbinate, and Eighteenth-Century Jewish Political Culture (PhD dissertation, New York University, 2012); and Abraham Schischa, “Rabbinic Writings from the Collection of Rabbi David Oppenheim,” Yeshurun 31 (2014): 781-794 (Hebrew).

For other significant personal Hebrew libraries and their purchasing history, see Binyamin Richler, Hebrew Manuscripts: A

Treasured Legacy (Clevland/Jerusalem: Ofeq Institute, 1990) 66-67.

Treasured Legacy (Clevland/Jerusalem: Ofeq Institute, 1990) 66-67.

[19] For earlier examples of private libraries see Nehemya Allony, The Jewish Library in the Middle Ages, Book Lists from the Cairo Genizah (Jerusalem: Ben-Zvi Institute, 2006); S.D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society (Berkley: University of California Press, 1967), vol. II, 206, 248; vol. V 3-4, 425.

[20] It is unclear whether Strashun meant this literally because while the 19th century witnessed the modern period of the public library, there were not any public libraries in Eastern Europe during Strashun’s lifetime.

[21] Shor, supra n. 4, at 26.

[22] Sefer Matat Yah, supra n. 9, at 35, listing Strashun’s bequests.

[23] Moshe Shimon Anktokolski, Evel Kaved, supra n.12, 17.

[24] Among those who had access during this time was Ya’akov Wallensky. During this time, Wallensky was writing his supplement to Piskei Teshuvot on Yoreh De’ah. Piskei Teshuvot itself is a collection of obscure and rare works discussing issues

appearing in Yoreh De’ah. Because Wallensky’s materials were even more obscure and rare, the only place he could access these was the Strashun Library. Ya’akov Wallensky, Daltei Teshuva, (Vilna, 1890), Introduction, 5-6, (link).

appearing in Yoreh De’ah. Because Wallensky’s materials were even more obscure and rare, the only place he could access these was the Strashun Library. Ya’akov Wallensky, Daltei Teshuva, (Vilna, 1890), Introduction, 5-6, (link).

[25] Shor, supra n. 4, at 29

[26] Cf. Aviva Astrinsky, “A Brief History of the Strashun Library,” in Yermiyahu Aharon Taub, ed., Mattityahu Strashun, 1817–1885: Scholar, Leader, and Book Collector (New York: YIVO Institute, 2001), iii, who provides that his collection was only

comprised of 5,739 items.

comprised of 5,739 items.

[27] Shor, supra n. 4, at 29. Regarding the conflicting reports of the Library’s locations during this period, see id., n.71.

[28] Shor, supra n.4, 32-3.

[29] While the Library moved to the new building in 1901, and its dedication ceremony occurred on April 14, 1902, it would not be until October 20, 1902, that the Library secured the necessary governmental permits to fully open to the public. See Shor at 34-35. The government license is reproduced in Layzer Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, vol. 2, (New York: Laureate Press, 1974),

346.

346.

[30] Frida Shor, supra n.4, 51-65,174-87. See Berger, “The Strashun Library in Vilna,” in Zevi Scharfstein, ed., Hebrew Education and Culture in Europe Between the Two World Wars (New York: Ogen Publishing House of Histadrut HaIvrit BeAmerica, 1957), 513 (Hebrew), who discusses the varied subject matter of the Library’s collection.

[31] Id.

[32] According to one account, the Library had over 200 patrons daily, but only 100 seats, forcing people to share chairs and encounter waits of over a half-hour just to enter the Library. Id. at 513.

[33] Ben Tzion Dinur, “Yerushalim de-Lita,” in Layzer Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, vol. 1 (New York: Laureate Press, 1974), XVI; but see the English translation of Dinur’s article that comingles the two groups and has both the Orthodox and younger generation studying “respona or modern Hebrew novels.” Id. at XX. It is unclear what accounts for this discrepancy in translation. Lucy S. Dawidwowicz, From That Place And Time, A Memoir 1938-1947, (New York: Bantam Books, 1991), 119, provides a remarkably similar account to Dinur’s (“On any day you could see, seated at the two long tables in the reading room,

venerable long-bearded men, wearing hats, studying Talmudic texts, elbow to elbow with bareheaded young men and even young women, bare-armed sometimes on warm days, studying their texts. The old men would sometimes mutter and grumble about what the world had come to. The young people would titter.”).

venerable long-bearded men, wearing hats, studying Talmudic texts, elbow to elbow with bareheaded young men and even young women, bare-armed sometimes on warm days, studying their texts. The old men would sometimes mutter and grumble about what the world had come to. The young people would titter.”).

For a breakdown of the Library’s readership by type (i.e. students, academics and public intellectuals, workers, etc.), see Berger, supra n. 28, 514-15.

[34] See Shor, supra n. 4, 174, see also the description of David Wolfson’s Vilna visit, Israel Klausner, “The Zionist Movement in

Lithuania,” in Yahdut Lita (Tel Aviv: Am Hasefer Publishers, 1950), 522 (Hebrew). For a photo of one such visit, see Layzer Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, vol. 2 (New York: Laureate Press, 1974), 416.

Lithuania,” in Yahdut Lita (Tel Aviv: Am Hasefer Publishers, 1950), 522 (Hebrew). For a photo of one such visit, see Layzer Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, vol. 2 (New York: Laureate Press, 1974), 416.

[35] Shor, supra n. 4, 174-75.

[36] Berger, “The Strashun Library in Vilna,” at 519; Shor, MeLekutei, supra n. 4, 169; Khaykl Lunski in Yeshurin’s ווילנע

(New York, 1935 – in Yiddish), p. 286-7

(New York, 1935 – in Yiddish), p. 286-7

[37] Abraham Joshua Heschel, “Yerushalim de-Lita,” in Ran, Jerusalem, vol. I, XVII; David E. Fishman, The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture (Pittsburgh, PA, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005), 143, provides that the holdings of the Strashun Library prior to the Holocaust was comprised of “some forty thousand volumes.”

[38] See Shor, MeLekutei, 38-9; 42 (discussing a 1926 public appeal that the Library undertook where it described its financial condition as “dire and catastrophic”); id. at 43 (“The Strashun Library underwent many difficult financial periods throughout the nineteen years of Polish rule (10/9/1920- 9/19/1939). But, it continued to major Vilna cultural institution.”).

[39] Shor, MeLekutei, 44-7.

[40] Sem C. Sutter, “The Lost Libraries of Vilna and the Frankfurt Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage,” in Lost Libraries, The Destruction of Great Book Collections Since Antiquity, ed. James Raven (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 220-22.

[41] Id. at 223 & 224 discussing other Vilna Libraries that were targeted by the Nazis. See also Dov Schidorsky, Burning Scrolls and Flying Letters (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2008), 165-201; David E. Fishman, The Rise of Modern Yiddish Culture (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005), 141-44; Frida Shor, supra n.4, 189-200.

[42] Sem C. Sutter, “The Lost Libraries of Vilna,” supra n.38, 224.

[43] Id. at 226.

[44] Berger, “The Strashun Library of Vilna,” at 517. The books that were not deemed important we pulped or used as heating fuel. Schidorsky, supra 39, 182. The exact date of when the Strashun Library was transferred to Germany is unclear; however, it was some date after April 1943. See David E. Fishman, supra n.39,173 n.9. Similarly unclear is the exact number of books that were sent to Frankfort. Sem C. Sutter, “The Lost Libraries of Vilna,” supra n.38, 228. But, according to Aviva Astrinsky, “almost all of the Strashun books were crated and shipped by rail to Germany. Aviva Astrinsky, “Mattitayahu (Mathis) Strashun,” supra n.24, i.

[45] See Ran, Jerusalem, vol II, 522, for a photo of post-war building. For a discussion regarding the numbers of books that survived from the Strashun Library, see Frida Shor, supra n.4, 204-05.

[46] Dov Schidorsky, supra n.39, 225, listing the countries and libraries who books were deposited at the Offenbach Depot. Sem C. Sutter, “The Lost Libraries of Vilna,” supra n.38, 229-32.

[47] Lisa Moses Leff, The Archive Thief: The Man who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust (United

States: Oxford University Press, 2015), 121.

States: Oxford University Press, 2015), 121.

[48] Id. at 124-30, 136-40.

[49] Id.

[50] Dov Schidorsky, supra n.39, 233, provides the numbers and location of heirless books returned by the Jewish Culture Reconstruction. For a listing of U.S. institutions that received heirless cultural property from the Offenbach Depot, see Herman

Dicker, Of Learning and Libraries, The Seminary Library at One Hundred, (New York: The Jewish Theological Seminary, 1988), Appendix B. See also F.J. Hoogewoud, The Nazi Looting of Books and its American ‘Antithesis’. Selected Pictures

from the Offenbach Archival Depot’s Photographic History and Its Supplement,” Studia Rosenthaliana 26:1-2 (1992): 158-192; and F.J. Hoogewoud, “Dutch Jewish Ex Libris found among looted books in the Offenbach Archival Depot (1946),” in Chaya Brasz and Yosef Kaplan, eds., Dutch Jews as Perceived by Themselves and by Others (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 247-261.

Dicker, Of Learning and Libraries, The Seminary Library at One Hundred, (New York: The Jewish Theological Seminary, 1988), Appendix B. See also F.J. Hoogewoud, The Nazi Looting of Books and its American ‘Antithesis’. Selected Pictures

from the Offenbach Archival Depot’s Photographic History and Its Supplement,” Studia Rosenthaliana 26:1-2 (1992): 158-192; and F.J. Hoogewoud, “Dutch Jewish Ex Libris found among looted books in the Offenbach Archival Depot (1946),” in Chaya Brasz and Yosef Kaplan, eds., Dutch Jews as Perceived by Themselves and by Others (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 247-261.

[51] Solomon B. Freehof, On the Collecting of Jewish Books, (New York, NY: Society of Jewish Bibliophiles, [196-]), 17; regarding the books that Hebrew University received, and its efforts to locate and claim heirless works throughout Europe through its Otzrot Ha-Goleh committee, see Shlomo Shunami, About Libraries and Librarianship, (Jerusalem: Rubin Mass, 1969), 56-65; Zvi Baras, A Century of Books, The Jewish National & University Library 1892-1992, (Jerusalem: Jewish National & Univ. Library,1992), nos. 94-101; Dov Schidorsky, supra n.39, 212-91.

[52] Dov Schidorsky, supra n. 39, 250-51.

[53] Id. at 248-50. According to Scholem, Abraham Ya’ari, Scholem’s partner on behalf of Hebrew University and its Goleh ha-Otzrot program, returned to Israel, in part, because of the difficulty in securing the necessary authorizations to enter Germany.

Id. 248; 351.

Id. 248; 351.

[54] Id. at 250-51.

[55] Id. at 251 n.51.

[56] See Druker, Of Learning and Libraries, 58. Druker, however, concludes that Tavel’s unilateral decision “resulted in

no real harm.” One wonders if any surviving heirs who had legal claims to the Manheim collection would reach the same conclusion.

no real harm.” One wonders if any surviving heirs who had legal claims to the Manheim collection would reach the same conclusion.

[57] Lucy S. Dawidwowicz, From That Place And Time, A Memoir 1938-1947, (New York: Bantam Books,1991), 314-16.

[58] See David E. Fishman, supra n.39, 143-53 174 n.20, discussing the YIVO Library under the Nazis and its ultimate transfer to YIVO in New York.

[59] Id. at 318.

[60] For more information regarding Weinreich and YIVO, see id. at 126-39.

[61] Id.; for a fuller treatment of this attempt see Shor, From ‘“Likute Shoshanim”, 44.

[62] Aside from Dawidowicz’s telling, according to the documents that discuss YIVO’s efforts to save its library and the Strashun and the Lithuanian government’s response throughout this attempt, the Strashun Library is described as a Vilna community

library and not the property of one institution or another. See Shor, From “Likutei Shoshanim”, at 44.

library and not the property of one institution or another. See Shor, From “Likutei Shoshanim”, at 44.

[63] Her argument has the perverse effect that the trustees attempt to save the library immediately resulted in completely losing control of the library.

[64] Aviva E. Astrinsky, Mattistyahu Strashun 1817-1885, Scholar, Leader, and Book Collector, YIVO, New York: 2001, ii, iv. But, Astrinsky also indicates that YIVO recovered “a substantial part of the Strashun Library.” Id. at i. According to YIVO’s website, however, YIVO only received part of the Strashun Library and the remainder “were transferred to the library of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. (link).

Similarly, Berger, “The Strashun Library in Vilna,” p. 517 claims that part of the Strashun Library went to YIVO and the other part to Hebrew University.

Similarly, Berger, “The Strashun Library in Vilna,” p. 517 claims that part of the Strashun Library went to YIVO and the other part to Hebrew University.

Beyond these unsupported statements, there is no evidence that any books from the Strashun Library were sent to the JNUL. While the JNUL’s post-war efforts at obtaining heirless books are well documented, see supra, there is no mention of the Strashun Library.

Similarly, the JNUL catalog does not list any items whose provenance extends to the Strashun Library. It is possible that YIVO and Berger confused the JNUL with the Jerusalem Central Library discussed below. Or simply conflated the Strashun Library with the numerous other European libraries that the JNUL successfully rescued.

Similarly, the JNUL catalog does not list any items whose provenance extends to the Strashun Library. It is possible that YIVO and Berger confused the JNUL with the Jerusalem Central Library discussed below. Or simply conflated the Strashun Library with the numerous other European libraries that the JNUL successfully rescued.

[65] See, e.g., the YIVO catalog entry for Solomon Adret’s Hidushe Nidah leha-Rashba, Altona, [1737].