Rabbi Zeira – Forgetting the Teachings of Babylon

Rabbi Zeira – Forgetting

the Teachings of Babylon

85a):

R. Zeira, when he moved to the land of

Israel, observed a hundred fasts to forget the teachings of Babylonia, [1] so

that they should not disturb him.

He fasted another hundred times so that R.

Elazar should not die during his years and the responsibilities of the

community not fall upon him.He fasted another hundred times so that

the fire of Gehenna should have no power over him.

forgetting the teachings of Babylonia:

contain many interactions between sages who travelled from the land of Israel

to Babylon or from Babylon to the land of Israel. These sages shared their own teachings

and traditions with their counterparts. By forgetting Babylonian teachings, R.

Zeira is choosing not to participate in this knowledge transfer. Why? [2]

the Jerusalem Talmud and sometimes he transmits in the name of his Babylonian

teachers. Many of these exchanges clearly took place when he already was in the

land of Israel. How can he transfer Torah information that he has supposedly forgotten?

[3]

when R Zeira was about to leave for the land of Israel, he went out of his way to

hear one more teaching from his teacher, Rav Yehuda. Why would he go to the trouble of amassing

more Babylonian teachings if he intended to immediately forget them?

isn’t a pious thing to do. The Mishna Pirkei Avot 3:10 strongly discourages it,

as does the Talmud: R. Elazar said: One who forgets a word of his learning (Talmud)

causes his descendants to be exiled – Yoma 38b. Resh Laqish said: One who forgets a word of his learning (Talmud)

transgresses a negative commandment – Menachot

99b.

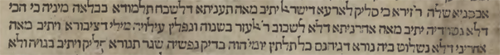

questions in one of the manuscripts of Baba Metzia, written around 1137

and housed in the National Central Library in Florence. The manuscript disagrees

with the premise that R. Zeira ever forgot his learning:

forget the teachings of Babylon.

R Il’a should not die in his lifetime.

Manuscript BM 85a

manuscripts that exist today in defining “not to forget” as the purpose R.

Zeira’s fast. [4] The manuscript is also attractive for a couple of other reasons:

than in the standard version. The explanations “when he moved to the land of

Israel”, “so that it should not disturb him”, [5] “so that the responsibilities

of the community not fall upon him” are all missing. This reduction most likely

indicates that the manuscript reflects an early version of the story – a

version in which marginal commentary had not yet been copied (inadvertently) into

the text.

R. Zeira (in all versions) tells of Rav Yosef (R. Zeira’s colleague) who also observed

a series of three sets of forty intermittent fasts. The purpose of Rav Yosef’s

fasts was to guarantee that the knowledge of the Torah would not depart from

himself, from his children and from his grandchildren. The goal of Rav Yosef’s

fasts seems to agree with the goal of R. Zeira’s fasts; to remember (i.e., not

forget) the teachings of Babylonia.

Zeira’s fasts have something in common with each other. He fasted so he would

not forget, he fasted so that R. Ila’i would not die, and he fasted so that the

fire of Gehina would not harm him. He always seems to be fasting so that

something should not happen.

the standard version, and no one (as far as I know) has relied on this reading

to resolve the original questions. [6]

are some of the classical interpretations that attempt to solve the problems of

R. Zeira’s forgetting.

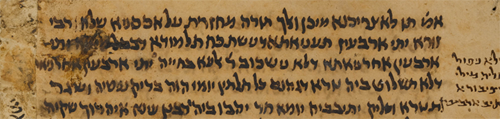

writes (BM 85a) that the students in the land of Israel were not בני מחלוקת, were not contentious, ונוחין זה לזה, they were pleasant to each other] . . . ומיישבין את

הטעמים בלא קושיות ופירוקין and they explained their reasoning without challenging each

other with difficulties and rebuttals.

to Rashi , R. Zeira forgets the “atmosphere” of the Babylonian academies. [7]

Rashi. He argues that the sages in the land of Israel do engage in questioning

and answering like their counterparts in Babylonia. He cites the Gemara (Baba Metzia 84a) where

R. Yohanan says about Reish Laqish: he

would raise twenty-four objections, and I would reply with twenty-four answers.

possibly the Babylonian piplul was faulty and similar to a style of piplul

that existed in his own time דוגמת חילוקים

שבדור הזה. He objects to this style of questioning and answering because it

distances one from the truth, and can’t help one rule on halakhic issues. Accordingly,

R. Zeira fasted in order to forget how to piplul the Babylonian way.

on Pirkei Avot (on the Mishna in chapter 5 which begins: There are four types

who study with the sages) writes somewhat similarly. The problem with the one who

is compared to a sponge, who soaks up everything – is that he retains things

that are untrue. In the search for truth, there are necessary steps which themselves

are untrue: כי לא תברר האמת כי אם בהפכו truth can only

be evaluated when compared with its opposite. R. Zeira fasts to forget the stages in

the arguments of the Babylonian Talmud that were untrue.

interpretations agree that R. Zeira didn’t literally forget the Babylonian

teachings. He forgot the “atmosphere” of the Babylonian academies or the

interim discussions that took place there. [8]

how the story of R. Zeira is presented in some early Hassidic sermons, to show

how the Rebbes and their audiences understood the story of R. Zeira. These

sources aren’t concerned with explaining our Gemara; R. Zeira’s story is cited

to support an ethical or moral lesson.

R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812). On

page 69c, in a discussion about spiritual worlds, the author says:

The purpose of the river diNur, (fiery

river (or maybe fiery light)), in which the soul submerges itself as it passes from

this world to Gan Eden, is to erase its memories of this physical world. If the

soul remembers its encounter with materiality, it can’t experience Gan Eden.

And when the soul goes from the lower Gan Eden to the higher Gan Eden it also must

pass through a river diNur to forget the comprehension and pleasures of the

lower Gan Eden. (Zohar part 2 210a) This is the idea in the Gemara: R. Zeira

observed 100 fasts to forget the Talmud of Babylonia even though he had studied

it with devotion.

of Bratslav (1772 – 1810) writes:

A

person sometimes has to feel self-important גדלות, as it says (2

Chronicles 17:6) His heart was elevatedויגבה לבו in

the service of G-d. This helps the same way

as fasting helps. For when one needs to attain an understanding or needs to

reach a higher level, he has to forget the wisdom he had previously acquired. R.

Zeira fasted to forget the Talmud of Babylon in order to reach a greater level

of comprehension – the level of the Talmud of the land of Israel. Similarly through self-importance, one forgets

his wisdom . . .

is no difficulty with the idea that R. Zeira forgets his learning in order to reach

higher spiritual plateau. Forgetting is a purification process that is both

necessary and exemplary. [9]

Gemara:

(1847-1914), the author of Dorot Harishonim addresses our problem in a footnote

(Dorot II p 427 footnote 93). He posits that in R. Zeira’s time there were already two canonized

collections of Talmudic material arranged around the Mishna; each in its own

distinct form and style.

וכן הי׳ להם אז כבר גם בארץ ישראל.

forget the Babylonian Talmud (as it existed in his time), because it interfered

with his studies in the land of Israel.

interpretation, R. Zeira forgot only the redaction or arrangement of the

teachings he had learned. He didn’t forget

the teachings themselves (or the study method). [10]

an original explanation. It’s based on passages in the Talmud about R. Zeira

and additionally can explain why only R. Zeira decided to forget the teachings

of Babylon when he moved to the land of Israel.

R.

Yitzhak b. Nahmani said in the name of R. Eleazar: The halakha agrees with R.

Jose b. Kipper. R. Zeira said: “If I

merit, I’ll go there and learn the halakha from the Master himself”. When R.

Zeira came to the land of Israel he found R. Eleazar and asked him: “Did you

say: The halakha is in agreement with R. Jose b. Kipper?” – Nidda 48a

R.

Zeira said to R. Abba b Papa: When you go there, detour around the Ladder of

Tyre and visit R. Yaakov b Idi. Ask him if he heard from R. Yohanan if the

Halakha is like R. Aqiba or not – Baba Metziah 43b

R

Zeira, commented: How can you compare R Binyamin b Yefet’s version of R.

Yohanan’s statement with the version of Rabbi Hiya b Abba. R Hiya b Abba was

precise when he studied the halakhic traditions from R Yohanan but R. Binyamin

b Yefet was not precise. Moreover, R Hiya b Abba reviewed his learning (Talmud)

with R. Yohanan every thirty days. – Berachot

38b

R.

Nathan b. Tobi quoted R. Johanan . . . Rabbi Zeira asked: “Did

R. Johanan say this?” Yes, he answered. Rabbi Zeira recited this teaching forty

times. R. Nathan said to R. Zeira: Is this the only teaching that you have

heard or is it a teaching that is new to you? R. Zeira replied: “It’s new to

me. I wasn’t sure if it was taught in the name R. Yohanan or R Yehoshua b

Levi.” – Berachot 28a

see that the teachings of the land of Israel (especially R. Yohanan’s) did

reach R. Zeira while he was still in Babylon [11]. R. Zeira, however, didn’t really

trust these teachings. Sometimes he thought they were attributed incorrectly,

or their content was not accurate. He doubted if a statement in the name of R.

Eleazar was correct. [12] He was unsure if R. Yohanan agreed with R. Aqiba’s

position or not. He distinguished between the different amoraim who

transmitted teachings. In general he looked at Torah that reached Babylon as

something that was possibly unreliable, inaccurate or “damaged in transit”.

only able to resolve his doubts when he moved to the land of Israel and learned

the Torah of the land of Israel there. He then forgot the imprecise version of

these teachings that he had previously memorized in Babylon – “the teachings of

Babylon”. He could forget them because they were superseded by accurate

teachings that he now received in the land of Israel. [13]

provided the cabbage rolls and coffee, and the late night sounding board.

as Babylonian Talmud, which I think is an anachronism. I will use the translation

“Babylonian teachings”. All the available manuscripts have תלמודא דבבל = the teachings of Babylonia. The phrase Talmuda

dBabel or Talmuda Babelah occurs only here

(Google). Talmud in the sense of teachings occurs many times, often in

comparison to mikra or mishna.

Compare Rosh Hashana 20b: “When R. Zeira went up [to the land of Israel], he

sent [a letter] to his colleagues [in Babylonia] . . .” R.

Zeira didn’t break off all contact with the old country. He taught them what he

heard and learned in the land of Israel.

and Babylonian Custom in Palestine” (Hebrew) Tarbiz vol. 36 1967 (pages

319-341), for examples of Babylonian traditions that R. Zeira brought to the

land of Israel. The following quote is from the online abstract:

Zeira is the outstanding figure among many who came from an area of unmixed

Babylonian tradition and who tried to impose their own Babylonian practice upon

Palestinian custom.”

The crucial word דלא, is crossed-out

in the manuscript, but I’m assuming that the strikethrough is not the work of

the original sofer. (Didn’t scribes write dots on top of the words they

wanted to erase?) The facsimile shows a number of other emendations that were written

after the manuscript’s creation.

him” would be out of place in this version of the story, since according to

this version, R. Zeria never forgot the Babylonian teachings, but the idea is

that the text is short. There is a geniza fragment from The Friedberg

Project for Talmud Bavli Variants and it is equally as short. (Note

that it matches the standard editions with regard to the goal of R. Zeira’s

fast.)

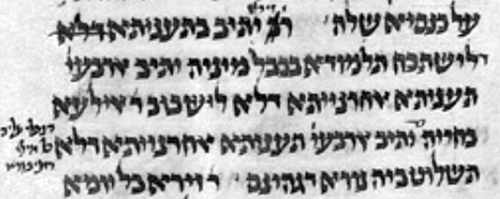

3 Geniza fragment

of our Baba Metziah 85a

the teachings of Babylon.

Il’a should not die in his lifetime.

Gehenna should have no power over him.

The author of Dikduke Soferim mentions this version but doesn’t suggest that its

reading is better than the standard one. Dikduke Sofreim has written elsewhere

that this specific manuscript belonged to Christians who translated (into Latin)

passages that were regularly used against Jews in inter-faith disputations.

There’s no Latin on this page, but you can see Latin on some other pages.

Rashi mentions his source as Sanhedrin 24a. He understands that the students of

Babylon were antagonistic to each other unlike the students in the land of

Israel who were pleasant to each other. Rashi apparently was thinking of this in

his commentary on the prayer of R. Nehunya ben HaKanah – Berachot 28b. The

prayer reads: “May it be Your will that I don’t make a mistake in a halakhic

ruling, and that my colleagues rejoice with me . . .” Rashi

understands the prayer this way – May it be Your will that I don’t make a

mistake in a halakhic ruling and my colleagues make fun of me.

The explanations of Maharsha and Abravanel have prompted subversive

interpretations by the school of the German Jewish historians of the

Talmud. In the Soncino translation of

Shabbat 41a, the translator, Rabbi DR. Freedman (1901-1982) writes: “Weiss, Dor, III, p. 188, maintains that R.

Zera’s desire to emigrate was occasioned by dissatisfaction with Rab Judah’s

method of study; this is vigorously combatted by Halevi, Doroth, II pp. 421 et

seq.”

in his book A History of the Jews in Babylonia page 218, also questions the

idea that sages of the land of Israel rejected the Babylonian methods of study,

and finds “Halevi’s strong demurrer quite convincing”.

In this context, the Talmudic statement: גדולה עבירה לשמה ממצווה שלא לשמה – מסכת הוריות י’ ע”ב may be somewhat

relevant.

Halevi, did R. Zeira also forget the

anonymous Talmudic layer (stam or redactor) that existed in his time?

The first of these conversations definitely took place in Babylon. The fourth

interaction occurred in the land of Israel but revises a teaching that R. Zeira

probably heard in Babylonia. The middle two quotes are may describe R. Zeira in

Babylon, but even if they occurred when R. Zeira was already in the land of

Israel, they reflect doubts that he had while in Babylon. The number 40 in the last example is also

remarkable. He repeats something 40 times in order to remember. He fasts 40

times to forget.

R. Eleazar teaches without citing his source but everyone knows that his

teachings are R. Yohanan’s (Yerushalmi Berakot 2:1 and Yerushalmi Shekalim 2:5).

Babylonian teachings, authored and recorded by the Babylonian amoraim. He

never doubted their accuracy. He brought those teachings to the land of Israel

and enriched the Torah of the land of Israel with them.