ArtScroll and More

There is one comment that I want to make right now regarding the pictures of the topless women that appeared and then disappeared in seforim. In addition to a point that I already once made that perhaps in earlier times the breasts were associated more with breastfeeding than with romance (it certainly was associated with that as well as can be seen from the Song of Songs, but not exclusively as today; perhaps it was more like a woman’s hair which can be seen in pictures), I would like to add a stronger point regarding these pictures.

It would seem to me that before photography when it wasn’t possible to produce real live looking pictures, people would be inclined to consider drawing an ערוה. But after the advent of real photographs, one gets the feeling that he is looking at a real image of a woman. It is for this reason, perhaps, that pictures of topless women became taboo. Once photographs began to be associated with ערוה, paintings and drawings followed since they are so similar to photographs. In other words, they became guilty by association.

If there is any merit to this argument (or speculation) then one can go a step further and say that the advent of color motion pictures which is more alive caused further stringency in this area. A picture of a woman is not that “problematic”, but to watch her video is already more like “mingling without a mechitza”. Once the women are struck from the videos, it is natural that they should be expunged from the magazines as well. It is worth noting that both the laws outlawing pornography and the invention of photography coincided with one another. It would seem that it wasn’t outlawed as long as it was only in the form of a drawing, painting, or sculpture.

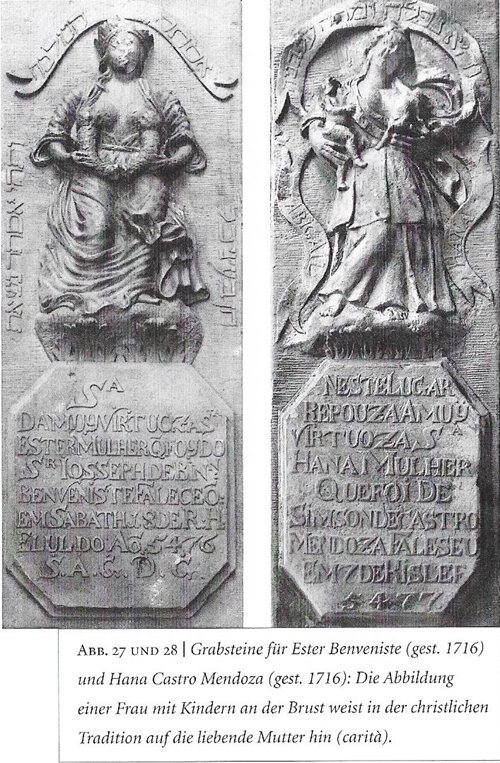

While it is true that earlier sources do speak of the sexual nature of breasts (see my post here note 19), I think that my correspondent has put his finger on a very important point. It would appear that breasts were more commonly associated with breastfeeding which meant that it was not problematic to show them in pictures. We even find such a portrayal on two tombstones in the old Sephardic cemetery in Altona. Here are the pictures as they appear in Michael Studemund-Halevy and Gaby Zuern, Zerstoert die Erinnerung Nicht. Der Juedische Friedhof Koenigstrasse in Hamburg (Munich, 2002), p. 109.

There are also a whole series of paintings and sculptures showing the Virgin Mary breastfeeding, obviously showing that this was not regarded as immodest in Christian circles.

The non-sexual nature of breasts also explains Shabbat 13a:

Another point which I think needs to be brought up about nude art is just how ubiquitous it was in Europe, statues, frescoes, and title pages in books, etc., very much influenced by Classical culture, which was of utmost importance in European learning and culture. If you’re in Venice or Prague or any major city in Europe you can’t avoid seeing it. The style of title pages may have changed, as styles do, so it is not surprising that Jewish printing culture changed as well. And eventually these seforim became one, two, and three centuries old and were only seen by individuals. Nudity in art was not ubiquitous in Eretz Yisrael and America, and it is not surprising that we woke up in the 20th century in American and EY and found these things surprising. My point is that it doesn’t necessarily have to do with them seeing breasts as sexual or not (what about thighs and bare midriffs? And seforim even depicted nude women bathing in the mikveh.) It is also important to note that in the writing of many great people they refer to specific editions they used, and it is clear that they saw it and neither defaced or said anything about it. So attitudes might be a European city vs. non-European city thing as well.

In an earlier post here I dealt with this picture which appears in the Venice 1574 edition of the Mishneh Torah.

[10] Meiri to Avodah Zarah p. 4.

[20] S. points out an interesting source which gives an unknown, but presumably true, biographical detail of R. Eybeschuetz’s life in the spiritual autobiography of an apostate Jew named Salomon Duitsch, A Short Account of the Wonderful Conversion to Christianity of Solomon Duitsch … Extracted from the Original Published in the Dutch Language (London 1771).S. wrote to me as follows:

Prone to mystical visions and ascetic practices like fasting, he was regarded locally as a tzadik, but he eventually became convinced of Christianity. When this became known was forced to divorce his wife. After a period of wandering he ended up in Altona. He still looked Jewish and his issues were unknown there. He writes of meeting and staying the night at R. Eybeschuetz, who was very delighted to host him on account that R. Eybeschuetz was educated and taken care of as an orphan in the house of his great-grandfather in Nikolsburg. This information about a Nikolsburg period in R. Eybeschuetz’s life, and who this great-grandfather might be, is not mentioned in the biographies, and is a reminder that much information about people’s lives is not necessarily in books.