“Be-Esek Atevata”: A Contextual Interpretation of an Elusive Phrase in Akdamut Millin

שְׁבַח ריבון עַלְמָא, אֲמִירָא דַכְוָתָא:

שְׁפַר עֲלֵיהּ לְחַווּיֵהּ, בְּאַפֵּי מַלְכְּוָתָא:

1 תָּאִין וּמִתְכַּנְשִׁין, כְּחֵיזוּ אַדְוָתָא:

2 תְּמֵהִין וְשַׁיְילִין לֵיהּ, בְּעֵסֶק אַתְוָתָא:

5 יְקָרָא וְיָאָה אַתְּ אִין תַּעַרְבִי לְמַרְוָתָא:

6 רְעוּתֵךְ נַעֲבֵיד לִיךְ, בְּכָל אַתְרְוָתָא:

2 Amazed, question one another about her signs

הִשְׁבַּעְתִּי אֶתְכֶם בְּנוֹת יְרוּשָׁלִָם אִם תִּמְצְאוּ אֶת דּוֹדִי מַה תַּגִּידוּ לוֹ שֶׁחוֹלַת אַהֲבָה אָנִי:

בְּנוֹת יְרוּשָׁלָיִם:

מַה דּוֹדֵךְ מִדּוֹד הַיָּפָה בַּנָּשִׁים מַה דּוֹדֵךְ מִדּוֹד שֶׁכָּכָה הִשְׁבַּעְתָּנוּ:

הָרַעְיָה:

דּוֹדִי צַח וְאָדוֹם דָּגוּל מֵרְבָבָה:

רֹאשׁוֹ כֶּתֶם פָּז קְוֻצּוֹתָיו תַּלְתַּלִּים שְׁחֹרוֹת כָּעוֹרֵב:

עֵינָיו כְּיוֹנִים עַל אֲפִיקֵי מָיִם רֹחֲצוֹת בֶּחָלָב יֹשְׁבוֹת עַל מִלֵּאת:

לְחָיָו כַּעֲרוּגַת הַבֹּשֶׂם מִגְדְּלוֹת מֶרְקָחִים שִׂפְתוֹתָיו שׁוֹשַׁנִּים נֹטְפוֹת מוֹר עֹבֵר:

יָדָיו גְּלִילֵי זָהָב מְמֻלָּאִים בַּתַּרְשִׁישׁ מֵעָיו עֶשֶׁת שֵׁן מְעֻלֶּפֶת סַפִּירִים:

שׁוֹקָיו עַמּוּדֵי שֵׁשׁ מְיֻסָּדִים עַל אַדְנֵי פָז מַרְאֵהוּ כַּלְּבָנוֹן בָּחוּר כָּאֲרָזִים:

חִכּוֹ מַמְתַקִּים וְכֻלּוֹ מַחֲמַדִּים זֶה דוֹדִי וְזֶה רֵעִי בְּנוֹת יְרוּשָׁלִָם:

בְּנוֹת יְרוּשָׁלָיִם:

אָנָה הָלַךְ דּוֹדֵךְ הַיָּפָה בַּנָּשִׁים אָנָה פָּנָה דוֹדֵךְ וּנְבַקְשֶׁנּוּ עִמָּךְ:

הָרַעְיָה:

דּוֹדִי יָרַד לְגַנּוֹ לַעֲרוּגוֹת הַבֹּשֶׂם לִרְעוֹת בַּגַּנִּים וְלִלְקֹט שׁוֹשַׁנִּים:

אֲנִי לְדוֹדִי וְדוֹדִי לִי הָרֹעֶה בַּשּׁוֹשַׁנִּים:

מכילתא דרבי ישמעאל בשלח – מסכתא דשירה ג

Also note how the poet’s תְּמֵהִין וְשַׁיְילִין לֵיהּ is taken nearly verbatim from the expression וכל האומות מסתכלין בהם ותמהין ואומרים of Bemidbar Rabba, which is used in the context of the flags.

Megilat Rut: The night of Boaz and Rut Revisited

The night of Boaz and Rut Revisited

Rut, Naomi tells Ruth to bathe herself, put on her [best] clothes and go down

at night to where Boaz is sleeping. Boaz then will “tell her” what to do. The

simple implication of this story is that Ruth would be sent to make a marriage

proposal to Boaz who could simply consummate the marriage immediately.[2]

that the story of Boaz and Ruth contains many elements of “yibum” procedure and

therefore it was concluded that at that time “yibum” was practiced by other

close relatives, not just the brother of the deceased.[4]

In theory Boaz could have relations with Ruth and thus do yibum immediately

that night, but since there was a closer kin[5]

he did not touch Ruth but waited until the morning. When in the presence of the

elders Boaz offered the closer relative to redeem the fields left for Ruth, he

was willing to do this, but when Boaz stipulated that he would have to marry

Ruth as well he refused saying: פֶּן אַשְׁחִית אֶת נַחֲלָתִי (lest I destroy

my “inheritance”). Hazal[6]

understand him to argue with Boaz’s opinion that a female from Moav is

permitted to “enter the congregation of Israel” i.e. marry a regular Jew. The

word “inheritance” is thus taken to mean descendants who will not be kosher

Jews and won’t be able to marry others in the Jewish nation[7].

understand a related issue: in the laws of yibum, what is the meaning of

(Devarim 25:6): “The first child born shall stand up in memory of the deceased

brother.” Hazal understand this not to mean the actual name of the person but

rather to be talking about inheritance belonging to the deceased brother.

However they explain[8]

that this inheritance is transferred to the brother that did the yibum.

According to Shadal[9] this

explanation was needed in order to encourage[10]

the brother to want to do yibum, but the original meaning of the Torah was

actually that yibum caused financial loss to the brother doing it as he would

not partake of the inheritance[11]

as it would all belong to the son born[12].

to discuss before we continue is the issue of “kri” and “ketiv”: “written” and

“read” forms of words. It is well known that certain words in Tanach are not

read the same way as they are written. The Talmud[13]

assumes that this is part of “halacha leMoshe miSinai[14]”

– part of oral traditions stemming from Moshe who received them at Mt. Sinai.

The difficulty with this is that many of these “kri” and “ketiv” forms are in

Neviim and Ketuvim – prophetic works written long after Moshe. R. Reuven

Margolies therefore concludes[15] that the expression “halacha leMoshe

miSinai” can mean a decision in some generation by the Great Sanhedrin[16].

Another explanation of “kri” and “ketiv” is offered by Radak[17]

and others: the two are preserved in some of the cases when different

manuscripts[18] had

different version of the word(s). Another possibility[19]

is that “kri” can be a kind of correction to the “ketiv” that the “Men of Great

Assembly” made for various reasons. Many of the “kri” and “ketiv” cases in fact

support this last opinion[20].

Some of the “kri” and “ketiv” differ only in that one of them reads as two

words what the other reads as one word. For example, the “ketiv” in “Devarim

39:2 is “Eshadot” but the “kri” is “Esh” “Dat” – fire of religion. Shadal[21]

writes that Dat is a Persian word and therefore the original meaning must have

been according to the “ketiv[22]”.

the key verse (4:5) has a “written” and “read” form:

וּמֵאֵת רוּת הַמּוֹאֲבִיָּה אֵשֶׁת הַמֵּת קָנִיתָה לְהָקִים שֵׁם הַמֵּת

עַל נַחֲלָתוֹ

that according to the ketiv (the written form) an opposite[24]

from traditional understanding immerges. According to “ketiv” Boaz did

consummate the marriage and when talking to the kinsman he says that Ruth is

already his wife. If he will later have a child from Ruth, the child will

inherit her husband’s property and the money the other relative paid to redeem

the field will go to waste.[25]

This then is the meaning of the other relative’s rejection of the offer (4:6):

<לגאול> לִגְאָל לִי פֶּן אַשְׁחִית אֶת נַחֲלָתִי גְּאַל לְךָ אַתָּה אֶת

גְּאֻלָּתִי כִּי לֹא אוּכַל לִגְאֹל:

meaning he would lose the field he would purchase.

Ruth on Shavuot, the simplest being that the main action takes place when

gathering barley and wheat crop, around the time of Shavuot.

interpretation, this is implied by Rut Rabbah 7:4. See also Taz, Yore Deah

192:1 who assumes this and discusses why the gezeira of seven days due to “dam

chimud” did not apply.

Devarim 25:6.

Batra 91a).

uncle.

marry Ruth since he already had another wife (see Targum ad loc) or so that his

older children won’t have to split the inheritance with his children from her

(see similarly Rema, Even Haezer 1:8).

halitzah, a financial incentive was used for this too, see Rema, Even Haezer

163:2.

want Tamar to have children.

the deceased thus the inheritance coming back to the original owner.

opinion in this sugia, see also Orach Chaim 141:8.

meaning. Various propositions have been offered regarding the relationship

between the two.

“halacha leMoshe miSinai” statements should not be taken literally see for

instance Rosh in the beginning of Mikvaot, see also Pesachim 110b.

Marc Shapiro, Limits of Orthodox Theology, page 101 who brings other

Rishonim that follow the same opinion. In one place in his commentary Radak

goes a step further and notices that Targum Yonatan seems to have a reading

where a letter is moved from the beginning of the word to the end of previous

word (Melachim 1:20:33, see also our next note).

in the times of Second Temple and probably before that as well. There are many

examples of this, see for instance Tosafot s.v. Maavirim and R. Akiva

Eiger, Shabbat 55b. One of the famous examples seems to be the well known

drasha in the Agada that criticizes the “wicked” son for excluding himself from

other participants: “lachem velo lo”. The obvious difficulty is that the wise son

also says: “etchem” (to you). Now we know that in some manuscripts the verse in

Devarim 6:20 indeed uses the expression “otanu” (us), see also Yerushalmi

Pesachim 10:4 (70b), Mechilta, end of Bo (chapter 18 in some editions,

paragraph 125 in others). Note also that many of the variants can be learned by

studying the old Torah translations, for instance Septuagint. It seems that

some of “deliberate changes” mentioned in Megila 9a-b were actually based on

variant manuscripts. In case of “naarei bnei yisrael”, we actually learn from

Masechet Sofrim 6:4 and parallel sources that there were variant manuscripts.

Additional examples can include “hamor” – “hemed” and “bekirba” – “bekroveah”,

where the words are very similar. R. Reuven Margolies in his “Hamikra Vahamesora”,

chapter 17 brings some interesting examples of translations that were based on

variant manuscripts. Without knowing this we can’t understand some words of

Hazal correctly. Just to bring two examples here, the question of how to read

“dodecha” in Shir Hashirim 1:2 (see Avoda Zara 29b) can be understood in light

of Septuagint translation as “breasts” (from the word “dad”; this also explains

why this particular question was asked when discussing the prohibition of

non-Jewish cheese; the verses describe that the Jewish nation’s wine, oil, and

breasts, i.e. milk are the best, and we should not use any of these products

made by non-Jews). In this example the difference with Masoretic text is only

in the vowels that are not written in the scrolls (see another example in

Mishley 12:28 that has in our Masoretic text “al mavet” – “not death” but

according to the Aramaic Targum the verse seems to read “el mavet” – “towards

death”). Another example with a real textual difference in consonants is in the

verse of Bereshit 26:32. The Bereshit Rabbah (end of 64) seems to at first not

be sure whether they found water or not. R. Reuven Margolies claims that the

uncertainty was whether the correct reading is “we did NOT find water” (based

on Septuagint translation) or “we found water” (as it is in our Masoretic

text). The difference is whether the word “Lo” should be with “Vav” (they said

to him) or with Aleph (they said: “we didn’t”, see however Rashash ad loc who

thinks that even according to the Masoretic text there is a possibility to

understand Lo with Vav as “not”).

to Yirmiyahu. This may be related to a similar question of what is “tikun

sofrim”, see R. Marc Shapiro, Limits of Orthodox Theology, starting

with page 98 and R. Saul Lieberman “Hellenism in Jewish Palestine”

starting with page 28. Indeed in

Midrash Tanchuma (Beshalach 16) the tradition is brought that tikun

sofrim is an actual change made by Anshey Kneset Hagedola.

synonym of “ketiv” but the expression used is a softer form, when the “ketiv”

is too crude, see Devarim 28:27 and 28:30, see also Talmud Bavli Megilah 25b.

the “ketiv” but most explain the meaning of verses according to the “kri”.

1982, page 171. He additionally writes based on discoveries in Ebla that ומאת is to be

understood not as “and from” but rather “but”. For Hazal’s understanding of

this “kri” and “ketiv” see Ruth Rabbah 7:10.

offer the exact opposite understanding.

It seems that according to the practice of the time a widow of a person was

able to enjoy some of the rights to his property or possibly make decision as

to which of the relatives takes possession of it.

An (almost) Unknown Halakhic Work by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi and an attempt to answer the question: who punctuated the first edition of the Shulhan Arukh?

An (almost) Unknown Halakhic Work by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of

Liadi and an attempt to answer the question: who punctuated the first edition

of the Shulhan Arukh?

by Chaim Katz

Chaim Katz is a

database computer programmer in Montreal Quebec. He graduated from McGill

University and studied in Lubavitch Yeshivoth in Israel and New York.

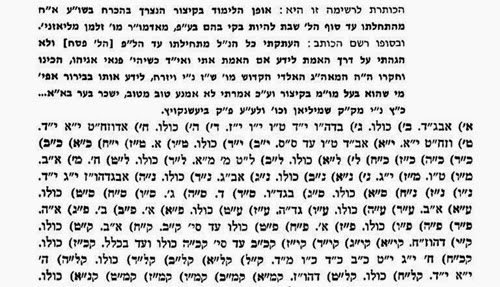

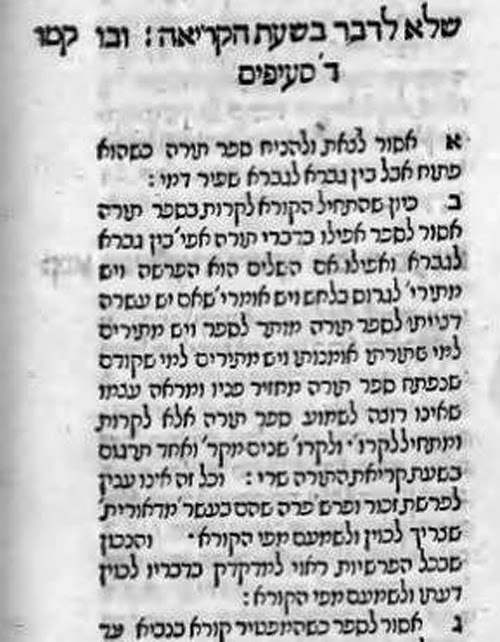

published a manuscript, which was a list of chapters and paragraphs (halakhot and se’fim), selected by Rabbi Shneur

Zalman of Liadi (RSZ), from the Shulhan Arukh (SA) of Rabbi Yosef Karo.[1]

(RYK)

Shneur Zalman and the preliminary and concluding notes written by R. Isakhar

Ber.

Isakhar Ber, who copied the original manuscript, explained the purpose of the

list in a preliminary remark:

of essential laws from the beginning of Shulhan Arukh Orah Hayim until the end of the Shabbat laws – to know them

fluently by heart, from Admur (our master, teacher and Rebbe), our teacher

Zalman of Liozna.

Isakhar also added an epilogue:

above, from the beginning until the laws of Pesah, but I didn’t check it

completely to verify that I copied everything correctly and G-d willing when

there’s time I will check it. Prepared and researched by the Rabbi and Gaon,

the great light, the G-dly and holy, our teacher, Shneur Zalman, may his lamp

be bright and shine, to know it clearly and concisely, even for those people who

are occupied in business. Therefore I thought I won’t withhold good from the

good. Isakhar Ber, son of my father and

master … Katz, may his lamp be bright, of the holy community of Shumilina and

currently in Beshankovichy.

manuscript was probably composed (or at least copied), between the years

1790-1801, when RSZ lived in Liozna. The existence of this list isn’t

acknowledged in any source that Rabbi Mondshine was aware of, and obviously the

list was never published in book form, either because RSZ

decided not to publicize it or because the list was simply put aside and

forgotten.

wasn’t the first who envisioned a popular digest of the SA. Rabbi Yehuda Leib

Maimon lists four works that preceded the famous Kitzur Shulhan Arukh.[2]

They preceded RSZ’s work as well and are all quite similar although they also

have their differences.

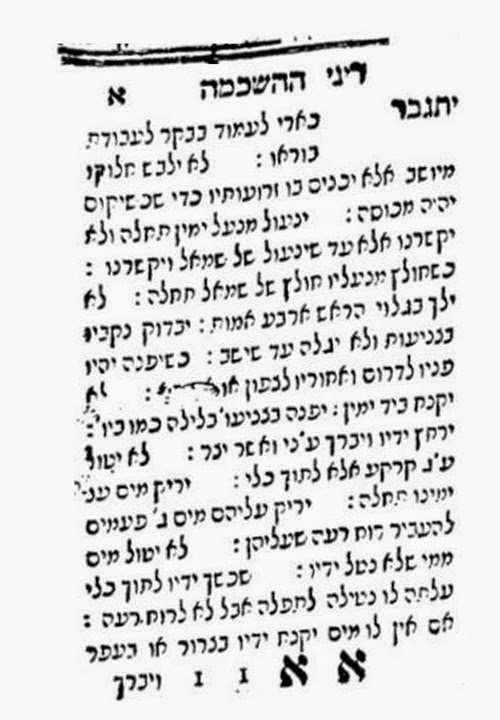

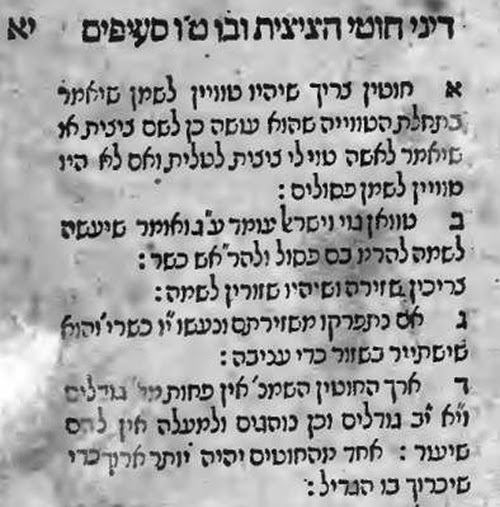

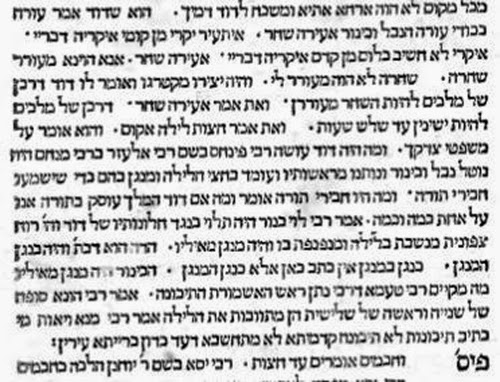

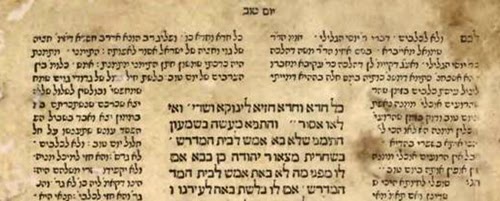

Figure 2: First edition of Shulhan Tahor by Rabbi Joseph Pardo (from

Hebrewbooks.org). The page summarizes three and a half chapters of the original

Shulhan arukh. Note how the author sometimes combines the words of RYK with the

words of Rema (line 11).

Others have a narrower scope and cover only Orah Hayim. RSZ covers even less.

Some collections are abbreviated extensively; others include more details.[3]

There are variations in the language and content; some quote opinions of later

authorities, some quote Kabbalah, some re-cast the language of the SA and some

retain the language as much as possible.

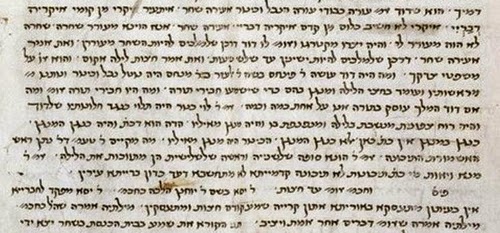

Hebrewbooks.org), composed in 1784. Note the author quotes Ateret Zekenim, (R.

MM Auerbach, published in 1702). The additions in parenthesis are by the

publisher of the 1879 edition.

two goals in mind. One of the goals was to make the basic rules and practices

of the SA more accessible. To this end, certain subjects or details were left

out because they were too technical for the chosen audience. Other rules were

omitted because the situations to which they applied happened only infrequently

(בדיעבד). Many regulations

were left out because daily life and its circumstances had changed so much

since the sixteenth century.

The other goal,

and arguably the primary goal, was to provide a text of law that could be

memorized. In the introduction to Shulhan Tahor, the author’s son writes:

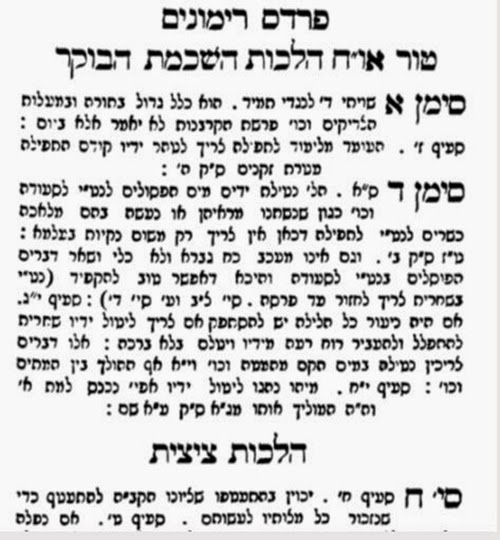

“every man will be familiar and fluent in these laws (שגורים בפי כל האדם)”. Likewise, the

author of Pardes Rimonim defines the purpose of his work: “so that the reader

will be fluent in these rules (שגורים

בפיו)

and will review them each month”. In

the introduction to the Shulhan Shlomo, the author writes: “Put these words to

your heart and you won’t forget them”, and the motive of R. Shneur Zalman’s

work is: “to know [these laws] fluently by heart”.

of the Shulhan Arukh, published in Venice in 1565 where memorization is

emphasized (from the scanned books at the website of the National Library of

Israel, (formerly the Jewish National and University Library.)

tradition of memorizing practical laws goes back to RYK himself, and probably

goes back even earlier.[4]

RYK writes in the introduction to his Shulhan Arukh:

that it is fitting to gather the flowers of the gems of the discussions [of the

Beit Yosef] in a shorter way, in a clear comprehensive pretty and pleasant

style, so that the perfect Torah of G-d will be recited fluently by each man of

Israel. When a scholar is queried about a law, he won’t answer vaguely.

Instead, he will answer: “say to wisdom

you are my sister”. As he knows his sister is forbidden to him, so he knows the

practical resolution of every legal question that he is asked because he is

fluent in this book… Moreover, the

young (rabbinical?) students will occupy themselves with it constantly and

recite its text by heart…

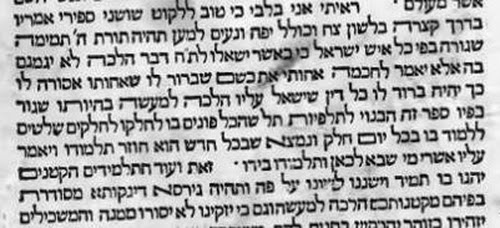

working on a phone version of RSZ’s work using the first print of

RYK’s SA for that portion of the text. However, (aside from the difficulty of

text justification in an EPUB), there is one typesetting decision that I’m

wondering about. The first edition of

the SA is punctuated with elevated periods and colons. The colons always separate each halakha, but

infrequently colons appear in the middle of a halakha. Sometimes followed by a

new line and sometimes not. The periods may appear in the middle of a halakha,

sometimes followed by horizontal white space and sometimes not.

much in the past 450 years; the colons at the end of each paragraph are present

in most current editions of the Shulan Arukh, but the periods, colons and white

space in the middle of the paragraphs have largely been ignored in subsequent

prints.[5]

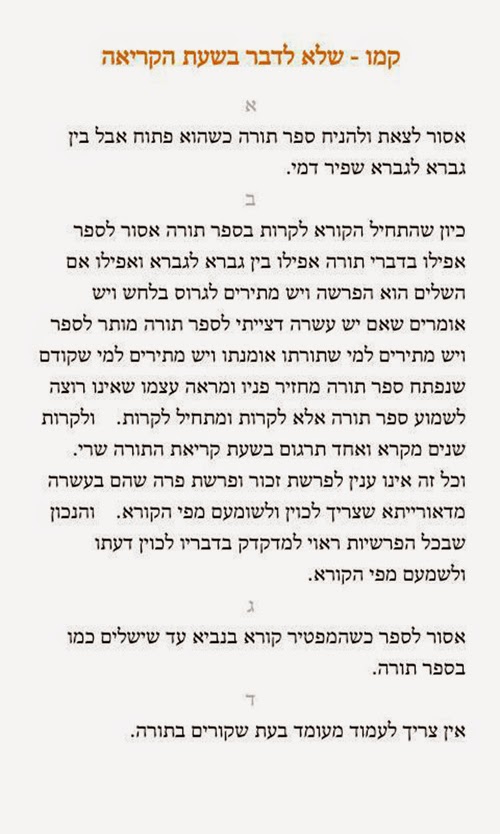

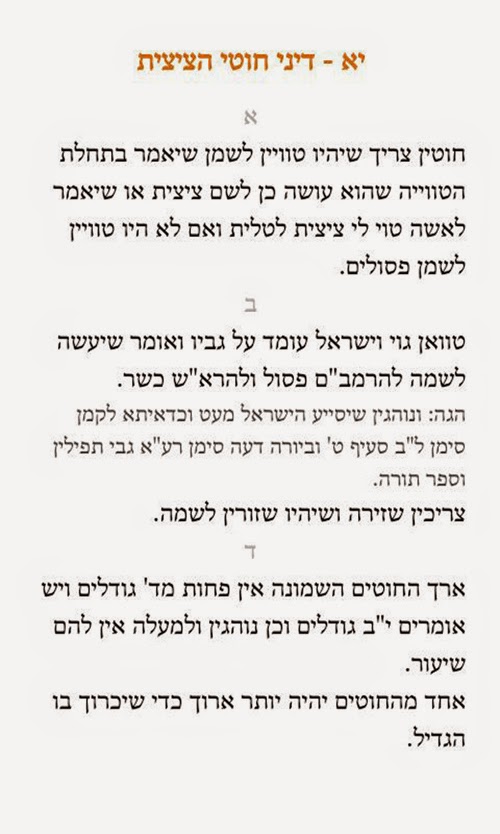

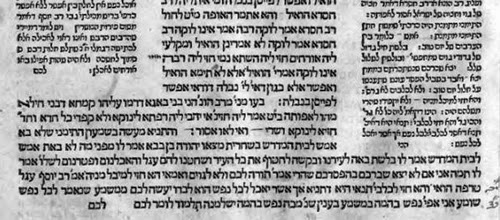

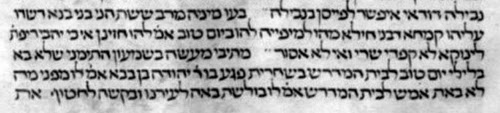

Do I try and duplicate this punctuation or not? Here are two examples where I

replaced the elevated period and colons with modern periods, but tried to keep

the original layout.

(from the National Library of Israel web site).

composition. Note periods and line feeds.

of chapter 11. See the colons in in the fourth halakha.

list – chapter 11

the punctuation of the first edition of the SA was copied from RYK’s manuscript. Prof.

Raz-Krakozkin writes: He (Karo) insisted on personally supervising its

publication and made sure that the editors followed his instructions[6]. On

the other hand, I can’t explain why the punctuation marks occur so rarely.

punctuated his manuscript before sending it to the printers, we can compare

other manuscripts that were printed then. For example, the Yerushalmi was first

printed in Venice (1523) from a manuscript, which is still extant today.

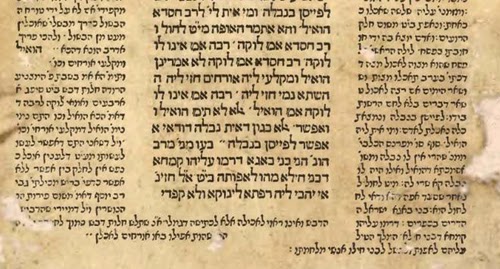

(Berakhot 1:1), with raised periods to separate word groups from the scanned

books at the website of the National Library of Israel, (formerly the Jewish

National and University Library.)

Yerushalmi has elevated periods that delineate groups of words. These markings

are already found in the source manuscript in the exact same places.

(1289 CE), Brakhot 1:1 from the Rabbinic Manuscripts on line at the National

Library of Israel web site, (formerly the Jewish National and University

Library).

speaks of two possibilities concerning the origin of the

Talmud Yerushalmi’s punctuation. The punctuation may be relatively recent – the

scribe punctuated the text or the punctuation existed in the manuscript that

the scribe copied from. Alternatively,

the punctuation might be a reduction or simplification of cantillation marks

that were common in much older rabbinic manuscripts. Either way, the printers

didn’t invent the punctuation.

dots”) in strategic places.[8]

These colons already exist in one of the first Talmud editions – the Bomberg

Talmud (Venice 1523).

colons. (The horizontal lines near the colons are either blemishes, or markings

by hand.) Note the horizontal white space after the colons.

edition were not printed from manuscript, but were copied from the Talmud

printed by Joshua Moses Soncino in 1484[9].

In the Soncino Talmud, we find separators in the exact places as the colons of

the Bomberg edition. The Soncino Talmud had two types of

punctuation: a top comma (or single quote mark) that marks off groups of words

(like the Yerushalmi has) and a double top comma (double quote mark). When

Bomberg printed his edition (40 years later), his printers replaced the double

commas with colons (and dropped the single commas).

page (21a) in Betza. Note the two elevated commas, where we have a colon and

the subsequent horizontal white space. (The Soncino Talmud does not have the

same pagination as us). From the National Library of Israel web site.

to our Betza 21a. Note again 2 commas where we have a colon.

We don’t know which manuscripts were used by the printers of the Babylonian

Talmud, and in any case the many Talmud burnings in the 1550’s in Italy

destroyed most of the manuscripts that were there. Nevertheless, there is at

least one old manuscript that has punctuation marks similar to what we find in

the Soncino Talmud.

manuscript showing the upper double comma separator for the same page – Betza

21a (From the Rabbinic Manuscripts on line at the National Library of Israel

web site, (formerly the Jewish National and University Library).)

The Gottingen manuscript is a Spanish

manuscript from the early thirteenth century[10] – almost three hundred years older than the Talmud printed

in Soncino. It doesn’t have the upper single commas that Soncino edition has,

but it does have the same double comma in the same places that the Soncino

print has. Just to repeat: the pauses

represented by colons, that we see in our Talmud are at least 800 years old!

punctuated just as the Talmudic manuscripts that he studied from were.

Summary

abbreviated (Kitzur) SA, and discussed it in the context of other similar

works. I mentioned that the authors aimed at producing collections of relevant laws

that could be memorized. I noted that the first edition of the SA was punctuated

differently from following versions. I suggested (based on comparisons with

early printed Talmuds) that the punctuation was probably the work of RYK and

not the work of the printers.

(1984). Migdal Oz (Hebrew), Kfar Habad: Machon Lubavitch , pp. 419-421. Dedicated to the memory of Rabbi

Azriel Zelig Slonim ob”m. Essays on Torah and Hassidut by our holy Rabbis, the

leaders of Habad and their students, collected from manuscripts and authentic

sources and assembled with the help of the Almighty.

Leib, The history of the Kitzur Shulhan Arukh (Hebrew), published in Rabbi Shlomo

Ganzfried, Kitzur Shulhan Arukh, Mossad Harav Kook Jerusalem Israel 1949. The

earlier works mentioned are: Shulan Tahor by R. Joseph Pardo,edited/financed by

his son David Pardo, Amsterdam 1686. Shulan Arukh of R. Eliezer Hakatan by Eliezer Laizer Revitz printed by his

son-in-law R. Menahem Azaria Katz, Furth

1697. Shulhan Shlomo by Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Mirkes printed in Frankfort

(Oder) 1771. Pardes Rimonim by R. Yehuda Yidel Berlin, composed in 1784 and

printed for the first time in Lemberg (Leviv) 1879.

beginning until the end of chapter 156 contains 18,000 words while the same

portion of the big Shulhan Arukh contains approximately 40,000 words. A word is

loosely defined as a group of characters separated by a space or by spaces.

the Mishne Torah, Maimonides writes: “I divided this composition into legal

areas by subject, and divided the legal areas into chapters, and divided each

chapter into smaller legal paragraphs so that all of it can be memorized.” See: Studies in the Mishne Torah, Book of

Knowledge Mossad Harav Kook, Jerusalem (Heb.) by Rabbi José Faur for a

discussion and explanation of the study methods of Middle Eastern Jews (page 46

and following pages, especially footnote 60).

Israel, (formerly the Jewish National and University Library) has the edition

of the Shulhan Arukh printed in Krakow in 1580. This is the second version with

the notes of the Rema (which was first printed in 1570) and it doesn’t have the

original punctuation marks.

to Venice: The Shulhan ‘Arukh and the Censor” (in: Chanita Goldblatt, Howard

Kreisel (eds.), Tradition, Heterodoxy and Religious Culture, Ben

Gurion University of the Negev (2007)

91-115).

A.M. Haberman, The First Editions of the Shulhan Arukh

(Heb.) on the daat.ac.il web

site, (from the journal Mahanaim # 97 1965 p 31-34.) suggests that the

editor/corrector of the first edition, Menahem Porto Hacohen

Ashenazi created its table of contents.

See also the discussion about who created the chapter headings, (a

pre-requisite for the table of contents), in Gates in Halakha (Heb.), Rabbi

Moshe Shlita, Jerusalem 1983, page 100. He argues that the chapter headings of

the Shulhan Arukh could not be the work of Rav Yosef Karo.

According to Ms Or 4720 of the Leiden University Library, Academy of the Hebrew

Language Jerusalem 2001 Introduction by Yaakov Sussmann.

beginning of Leviticus “What is the purpose of the horizontal white-space (in

the text of the Torah)? It gives Moshe some space to contemplate between a

section and the next section, between a topic and the next topic. (Rashi Lev. 1:1 s.v. vayikra el Moshe (2nd)

from the Sifra.

Rabbinovicz. Essay on the printing of the Talmud (Hebrew).

Oral Torah, Halakha, Mishna, Tosefta, Talmud, External Tractates (Compendia

Rerum Iudaicarum Ad Novum Testamentum)

The Princess and I: Academic Kabbalists/Kabbalist Academics

Kabbalists/Kabbalist Academics

Assistant Rabbi at Lincoln Square Synagogue and on the Judaic Studies Faculty

at SAR High School.

contribution to the Seforim blog. His

first essay, on “The Nazir in New York,” is available (here).

have witnessed the veritable explosion of “new perspectives” and

horizons in the academic study of Kabbalah and Jewish Mysticism. From the

pioneering work of the late Professor Gershom Scholem, and the establishment of

the study of Jewish Mysticism as a legitimate scholarly pursuit, we witness a

scene nowadays populated by men and women, Jews and non-Jews, who have

challenged, (re)constructed, and expanded upon Scholem’s work.[2]

variously praised and criticized themselves for sometimes blurring the lines

between academician and practitioner of Kabbalah and mysticism.[3]

Professor Boaz Huss of the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev has done

extensive work in this area.[4]

One of the most impressive examples of this fusion of identities is Professor

Yehuda Liebes (Jerusalem, 1947-) of Hebrew University, who completed his

doctoral studies under Scholem, and rose to prominence himself by challenging

scholarly orthodoxies established by his mentor.

initial encounter between so-called ‘traditional’ notions of Kabbalah and

academic scholarship was a jarring one, calling into question aspects of faith

and fealty to long-held beliefs.[5]

In a moment of presumption, I would imagine that this same process is part and

parcel of many peoples’ paths to a more mature and nuanced conception of Torah

and tradition, having undergone the same experience. The discovery of

scholar/practitioners like Prof. Liebes, and the fusion of mysticism and

scholarship in their constructive (rather than de-constructive) work has served

to help transcend and erase the tired dichotomies and conflicts that previously

wracked the traditional readers’ mind.[6]

in honor of the 33rd of the ‘Omer –

the Rosh ha-Shana of The Zohar and

Jewish Mysticism that I present here an expanded and annotated translation of

Rabbi Menachem Hai Shalom Froman’s poem and pean to his teacher, Professor

Yehuda Liebes.[7]

Study of the unprecedented relationship between the two, and other

traditional/academic academic/traditional Torah relationships remains a

scholarly/traditional desideratum.[8]

was born in 1945, in Kfar Hasidim, Israel,

and served as the town rabbi of Teko’a in the West Bank of Israel.

During his military service, served as an IDF paratrooper and was one of the

first to reach the Western Wall.. He was a student of R. Zvi Yehuda Kook at

Yeshivat Merkaz ha-Rav and also studied Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University

of Jerusalem. A founder of Gush Emunim, R. Froman was the founder of Erets Shalom and advocate of

interfaith-based peace negotiation and reconciliation with Muslim Arabs. As a

result of his long-developed personal friendships, R. Froman served as a

negotiator with leaders from both the PLO and Hamas. He has been called a

“maverick Rabbi,” likened to an “Old Testament seer,”[9]

and summed him up as “a very esoteric kind of guy.”[10]

Others have pointed to R. Froman’s expansive and sophisticated religious

imagination; at the same time conveying impressions of ‘madness’ that some of

R. Froman’s outward appearances, mannerisms, and public activities may have

engendered amongst some observers.[11] He passed

away in 2013.

for his written output, although recently a volume collecting some of his

programmatic and public writing has appeared, Sahaki ‘Aretz (Jerusalem: Yediot and Ruben Mass Publishers: 2014).[12]

I hope to treat the book and its fascinating material in a future post at the Seforim blog. [13]

by Josh Rosenfeld

and leaping[14]

had opened to love

father to be his wife[16]

and leaping

men amidst the longing of doves[17]

moment of intimacy

embrace of parting moment[18]

and leaping

had left her in pain

honor of her father and the garb of royals

and he danced

glory of his God

the troubles in hers

herds

leaping he loved

wish to join with those who are honoring my teacher and Rebbe Muvhak [ =longtime teacher] Professor Yehuda Liebes, shlit”a [ =may he merit long life]

(or, as my own students in the Yeshiva are used to hearing during my lectures, Rebbe u’Mori ‘Yudele’ who disguises himself

as Professor Liebes…).

according to its authorial intent), describes the ambivalent relationship

between two poles; between Mikhal, the daughter of Saul, who is connected to

the world of kingship and royalty, organized and honorable – and David, the

wild shepherd, a Judean ‘Hilltop Youth’ [ =no’ar

gev’aot]. Why did I find (and it pleases me to add: with the advice of my

wife) that the description of the complex relationship between Mikhal, who

comes from a yekkishe family, and

David, who comes from a Polish hasidishe family, is connected to [Prof.] Yehuda

[Liebes]? (By the way, Yehuda’s family on his father’s side comes from a city

which is of doubtful Polish or German sovereignty). Because it may be proper,

to attempt to reveal the secret of Yehuda – how it is possible to bifurcate his

creativity into the following two ingredients: the responsible, circumspect (medu-yekke)

scientific foundation, and the basic value of lightness and freedom.

(as he analyzes with intensity in his essay “Zohar and Eros”[19]),

formality and excess (as he explains in his book, “The Doctrine of

Creation according to Sefer Yetsirah“[20]),

contraction and expansion, saying and the unsaid, straightness ( =shura)

and song ( =shira). Words that stumble in the dark, seek in the murky mist,

for there lies the divine secret. Maimonides favors the words: wisdom and will;

and in the Zohar, Yehuda’s book, coupling and pairs are of course, quite

central: left as opposed to right, might ( =gevura)

as opposed to lovingkindness ( =hesed),

and also masculinity as opposed to the feminine amongst others. I too, will

also try: the foundation of intellectualism and the foundation of sensualism

found by Yehuda.

aspects of Yehuda’s creativity mesh together to form a unity? This poem, which

I have dedicated to Yehuda, follows in the simple meaning of the biblical story

of the love between Mikhal and David, and it does not have a ‘happy ending’;

they separate from each other – and their love does not bear fruit. Here is

also the fitting place to point out that our Yehuda also merited much criticism

from within the academic community, and not all find in his oeuvre a unified

whole or scientific coherence of value. But perhaps this is to be instead found

by his students! I am used to suggesting in my lectures my own interpretation

of ‘esotericism’/secret: that which is impossible to [fully] understand, that

which is ultimately not logically or rationally acceptable.

story ‘in praise of Liebes’ (Yehuda explained to me that he assumes the meaning

of his family name is: one who is related to a woman named Liba or, in the changing of a name, one who is related to an Ahuva/loved one). As is well known, in

the past few years, Yehuda has the custom of ascending ( =‘aliya le-regel)[21]

on La”g b’Omer to the

celebration ( =hilula) of

RaShb”I[22]

in Meron. Is there anyone who can comprehend – including Yehuda himself – how a

university professor, whose entire study of Zohar is permeated with the notion

that the Zohar is a book from the thirteenth- century (and himself composed an

entire monograph: “How the Zohar Was Written?”[23]), can be

emotionally invested along with the masses of the Jewish people from all walks

of life, in the celebration of RaShb”I, the author of the Holy Zohar?

asked me to join him on this pilgrimage to Meron, and I responded to him with

the following point: when I stay put, I deliver a long lecture on the Zohar to

many students on La”g b’Omer,

and perhaps this is more than going to the grave of RaShb”I.[24]

Yehuda bested me, and roared like a lion: “All year long – Zohar, but on La”g b’Omer – RaShb”I!”

covenant makes it known.[25]

[2] It is no understatement to say that there is a vast literature on the late Professor Gershom Scholem and for an important guide, see Daniel Abrams, Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory: Methodologies of Textual Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of Jewish Mysticism, second edition (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2014). See also Gershom Scholem’s Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism 50 Years After: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on the History of Jewish Mysticism, eds. Joseph Dan and Peter Schafer (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1993), 1-15 (“Introduction by the Editors”); Essential Papers on Kabbalah, ed. Lawrence Fine (New York: NYU Press, 1995); Mysticism, Magic, and Kabbalah in Ashkenazi Judaism, eds. Karl Erich Grozinger and Joseph Dan (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1995); Kabbalah and Modernity: Interpretations, Transformations, Adaptations, eds. Boaz Huss, Marco Pasi and Kocku von Stuckrad (Leiden: Brill, 2010), among other fine works of academic scholarship.

[3] While representing a

range of academic approaches, these scholars can be said to have typified a

distinct phenomenological approach to the academic study of Kabbalah and what

is called “Jewish Mysticism.” See Boaz Huss, “The Mystification

of Kabbalah and the Myth of Jewish Mysticism,” Peamim 110 (2007): 9-30 (Hebrew), which has been shortened into

English adaptations in Boaz Huss, “The Mystification of the Kabbalah and

the Modern Construction of Jewish Mysticism,” BGU Review 2 (2008), available online (here);

and Boaz Huss, “Jewish Mysticism in the University: Academic Study or

Theological Practice?” Zeek (December 2006), available online (here).

“Spirituality: The Emergence of a New Cultural Category and its Challenge

to the Religious and the Secular,” Journal

of Contemporary Religion 29:1 (January 2014): 47-60; see further in Boaz

Huss, “The Theologies of Kabbalah Research,” Modern Judaism 34:1 (February 2014): 3-26; and Boaz Huss,

“Authorized Guardians: The Polemics Of Academic Scholars Of Jewish Mysticism

Against Kabbalah Practitioners,” in Olav Hammer and Kocku von Stuckrad,

eds., Polemical Encounters: Esoteric

Discourse and Its Others (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 85-104. On the difficulty

of pinning down just what is meant by the word ‘mysticism’ here, see Ron

Margolin, “Jewish Mysticism in the 20th Century: Between Scholarship and

Thought,” in Haviva Pedaya and Ephraim Meir, eds., Judaism: Topics, Fragments, Facets, and Identities – Sefer Rivkah

(=Rivka Horwitz Jubilee Volume) (Be’er Sheva: Ben Gurion University, 2007;

Hebrew), 225-276; see also the introduction to Peter Schäfer, The Origins of Jewish Mysticism

(Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009), 1-31, especially 10-19, where Schäfer attempts

to give a precis of the field and the various definitions of what he terms

“a provocative title.” See

Boaz Huss, “Spirituality: The Emergence of a New Cultural Category and its

Challenge to the Religious and the Secular,” Journal of Contemporary

Religion 29:1 (January 2014): 47-60; see further in Boaz Huss, “The

Theologies of Kabbalah Research,” Modern Judaism 34:1 (February 2014):

3-26; and Boaz Huss, “Authorized Guardians: The Polemics Of Academic

Scholars Of Jewish Mysticism Against Kabbalah Practitioners,” in Olav

Hammer and Kocku von Stuckrad, eds., Polemical Encounters: Esoteric Discourse

and Its Others (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 85-104.

pinning down just what is meant by the word ‘mysticism’ here, see Ron Margolin,

“Jewish Mysticism in the 20th Century: Between Scholarship and

Thought,” in Haviva Pedaya and Ephraim Meir, eds., Judaism: Topics,

Fragments, Facets, and Identities – Sefer Rivkah (=Rivka Horwitz Jubilee

Volume) (Be’er Sheva: Ben Gurion University, 2007; Hebrew), 225-276; see also

the introduction to Peter Schäfer, The

Origins of Jewish Mysticism (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009), 1-31,

especially 10-19, where Schäfer attempts to give a precis of the field and the

various definitions of what he terms “a provocative title,” as well

earlier in Peter Schäfer, Gershom Scholem

Reconsidered: The Aim and Purpose of Early Jewish Mysticism (Oxford, U.K.:

Oxford Centre for Postgraduate Hebrew Studies, 1986).

sometimes fraught encounter and oppositional traditional stance regarding the

academic study of Kabbalah, see Jonatan Meir, “The Boundaries of the

Kabbalah: R. Yaakov Moshe Hillel and the Kabbalah in Jerusalem,” in Boaz

Huss, ed., Kabbalah and Contemporary

Spiritual Revival (Be’er Sheva: Ben Gurion University Press, 2011),

176-177. Inter alia, Meir discusses

the adoption of publishing houses like R. Hillel’s Hevrat Ahavat Shalom of “safe” academic practices such as

examining Ms. for textual accuracy when printing traditional Kabbalistic works.

See also R. Yaakov Hillel, “Understanding Kabbalah,” in Ascending Jacob’s Ladder (Brooklyn:

Ahavat Shalom Publications, 2007), 213-240; and the broader discussion in

Daniel Abrams, “Textual Fixity and Textual Fluidity: Kabbalistic

Textuality and the Hypertexualism of Kabbalah Scholarship,” in Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory:

Methodologies of Textual Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of

Jewish Mysticism, second edition (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2014), 664-722.

overview of Liebes’ work, see Jonathan Garb, “Yehuda Liebes’ Way in the

Study of the Jewish Religion,” in Maren R. Niehoff, Ronit Meroz, and

Jonathan Garb, eds., ve-Zot le-Yehuda –

And This Is For Yehuda: Yehuda Liebes Jubilee Volume (Jerusalem: Mosad

Bialik, 2012), 11-17 (Hebrew); and for an example of a popular treatment of

Liebes, see Dahlia Karpel, “Lonely Scholar,” Ha’aretz (12 March 2009), available online here

(http://www.haaretz.com/lonely-scholar-1.271914).

first published in Menachem Froman, “The King’s Daughter and I,” in

Maren R. Niehoff, Ronit Meroz, and Jonathan Garb, eds., ve-Zot le-Yehuda – And This Is For Yehuda: Yehuda Liebes Jubilee Volume

(Jerusalem: Mosad Bialik, 2012), 34-35 (Hebrew). The translation and

annotation of this essay at the Seforim

blog has been prepared by Josh Rosenfeld.

[8] For

a sketch of the (non)interactions of traditional and academic scholarship in

the case of Gershom Scholem, see Boaz Huss, “Ask No Questions: Gershom

Scholem and the Study of Contemporary Jewish Mysticism,” Modern Judaism 25:2 (May 2005) 141-158. See also Shaul Magid, “Mysticism,

History, and a ‘New’ Kabbalah: Gershom Scholem and the Contemporary

Scene,” Jewish Quarterly Review

101:4 (Fall 2011): 511-525; and Shaul Magid, “‘The King Is Dead [and has

been for three decades], Long Live the King’: Contemporary Kabbalah and

Scholem’s Shadow,” Jewish Quarterly

Review 102:1 (Winter 2012): 131-153.

[9] See

the obituary in Douglas Martin, “Menachem Froman, Rabbi Seeking Peace,

Dies at 68,” The New York Times (9 March 2013), available online (here).

Speaking to a member of the Israeli media at R. Froman’s funeral, the author

and journalist Yossi Klein Halevi described “Rav Menachem” as

“somebody who, as a Jew, loved his people, loved his land, loved humanity

– without making distinctions, he was a man of the messianic age, he saw

something of the redemption and tried to bring it into an unredeemed

reality,” available online here (here).

[10] R. Froman’s mystical

political theology permeated his own personal existence. Even on what was to

become his deathbed, he related in interviews how he conceived of his illness

in terms of his political vision: “How do you feel?” “You are

coming to me after a very difficult night, there were great miracles. It is

forbidden to fight with these pains, we must flow with them, otherwise the pain

just grows and overcomes us. This is what there is, this is the reality that we

must live with. Such is the political

reality, and so too with the disease.” (Interview with Yehoshua

Breiner, Walla! News Org.; 3/4/13, emphasis mine)

[11] See, for example, the

short, incisive treatment of Noah Feldman, “Is a Jew Meshuga for Wanting

to Live in Palestine?” Bloomberg

News (7 March 2013), available online (here),

who concisely presents the obvious paradox of “The Settler Rabbi” who

nevertheless advocates for a Palestinian State, and outlines the central

challenges to R. Froman’s “peace theology” from practical security

concerns for Jews living in such a state to the challenges of unrealistic

idealism in R. Froman’s thought.

of the first translations of some of Sahaki

‘Aretz’ fascinating material, can be seen online (here).

overview of R. Froman’s literary output and sui generis personality is the

forthcoming essay by Professor Shaul Magid, “(Re)Thinking American Jewish

Zionist Identity: A Case for PostZionism in the Diaspora.” To the best of

my knowledge, Professor Magid’s currently unpublished essay is the first

scholarly treatment of R. Froman’s writings in Sahaki ‘Aretz, although see the brief review by Ariel Seri-Levi,

“The Vision of the Prophet Menachem, Rebbe Menachem Froman,” Ha’aretz Literary Supplement (9 February

2015; Hebrew). I would like to thank Menachem Butler for introducing me to

Professor Magid.

referred to as the badhana d’malka,

or “Jester of the King” (see Zohar, II:107a); Liebes treats the

subject at length in Yehuda Liebes, “The Book of Zohar and Eros,” Alpayim 9 (1994): 67-119 (Hebrew).

parallel, sometimes oppositional, and rarely unified relationships between the

two royal lineages of Joseph and Judah, see the remarkable presentation of R.

Mordechai Yosef Leiner of Izbica (1801-1854), Mei ha-Shiloah, vol. 1, pp. 47-48, 54-56. On these passages, see

Shaul Magid, Hasidism on the Margin:

Reconciliation, Antinomianism, and Messianism in Izbica/Radzin Hasidism

(Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), 120, 147, 154, et al. The

marriage of David to Mikhal, daughter of Saul, represented an attempted

mystical fusion of the two houses and their perhaps complementary spiritual

roots, as R. Froman alludes to later in his essay.

5:2. See, most recently, Michael Fishbane, The

JPS Bible Commentary: Song of Songs (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication

Society, 2015), 75-76, 133-135.

b. Yoma 54b with commentary of Rashi.

“The Book of Zohar and Eros,” Alpayim

9 (1994): 67-119 (Hebrew)

Poetica in Sefer Yetzirah (Jerusalem:

Schocken, 2000; Hebrew) and see the important review by Elliot R. Wolfson, “Text,

Context, and Pretext: Review Essay of Yehuda Liebes’s Ars Poetica in Sefer Yetsira,” Studia Philonica Annual 16 (2004): 218-228.

essay, where we defined Lag ba-Omer in

the sense of the Kabbalistic/Mystical Rosh ha-Shana. For an overview of Lag ba-Omer and it’s unique connection

to the study of the Zohar, see Naftali Toker, “Lag ba-Omer: A Small Holiday of Great Meaning and Deep

Secrets,” Shana beShana (2003):

57-78 (Hebrew), available online (here).

“Holy Place, Holy Time, Holy Book: The Influence of the Zohar on

Pilgrimage Rituals to Meron and the Lag ba-Omer Festival,” Kabbalah 7 (2002): 237-256 (Hebrew).

“How the Zohar Was Written,” in Studies

in the Zohar (Albany: SUNY Press, 1993), 85-139. For an exhaustive survey

of all of the scholarship on the authorship of the Zohar, see Daniel Abrams,

“The Invention of the Zohar as a Book” in Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory: Methodologies of Textual

Scholarship and Editorial Practice in the Study of Jewish Mysticism, second

edition (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 2014), 224-438.

life, R. Froman delivered extended meditations/learning of Zohar and works of

the Hasidic masters in a caravan at the edge of the Teko’a settlement in Gush

Etzion. These ‘arvei shirah ve-Torah

were usually joined by famous Israeli musicians, such as the Banai family and

Barry Sakharov. One particular evening was graced with Professor Liebes’

presence, whereupon Liebes and Froman proceeded to jointly teach from the

Zohar. It is available online (here).

connection of this verse with the 33rd of the ‘Omer, see R. Elimelekh of Dinov, B’nei Yissachar: Ma’amarei

Hodesh Iyyar, 3:2. For an exhaustive discussion of the 33rd day of the

‘Omer and its connection with Rashbi, see R. Asher Zelig Margaliot (1893-1969),

Hilula d’Rashbi (Jerusalem: 1941),

available online (here), On R. Asher

Zelig Margaliot, see Paul B. Fenton, “Asher Zelig Margaliot, An Ultra

Orthodox Fundamentalist,” in Raphael Patai and Emanuel S. Goldsmith, eds.,

Thinkers and Teachers of Modern Judaism (New York: Paragon House, 1994), 17-25;

and see also Yehuda Liebes, “The Ultra-Orthodox Community and the Dead Sea

Scrolls,” Jerusalem Studies in

Jewish Thought 3 (1982): 137-152 (Hebrew), cited in Adiel Schremer,

“‘[T]he[y] Did Not Read in the Sealed Book’: Qumran Halakhic Revolution

and the Emergence of Torah Study in Second Temple Judaism,” in David

Goodblatt, Avital Pinnick, and Daniel R. Schwartz, eds., Historical Perspectives from the Hasmoneans to Bar Kokhba in Light of

the Dead Sea Scrolls (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 105-126. R. Asher Zelig

Margaliot’s Hilula d’Rashbi is

printed in an abridged form in the back of Eshkol Publishing’s edition of R.

Avraham Yitzhak Sperling’s Ta’amei

ha-Minhagim u’Mekorei ha-Dinim and for sources and translations relating to

the connection of RaShb”I and the pilgrimage (yoma d’pagra) to his grave in Meron, see (here).