Some Notes on Censorship of Hebrew Books

by Norman Roth

Habent sua fata libelli (Books have their fate)

One of the tragedies of the Inquisition and the Expulsions – both from Spain and Portugal– which has received very little attention is the destruction and loss of Hebrew manuscripts and books. Since the printing of Hebrew books in Spain began many years before the Expulsion, this loss involved printed books as well as manuscripts. Indeed, due to these losses, since only fragments survive of some of the earliest examples of Hebrew printing in Spain it may be impossible to ever know with certainty when this printing actually began. [1]

The edict of Expulsion (1492) caught the Jews of Spain completely by surprise. Even though extensions were granted, it was not always possible to arrange for the transport of books, perhaps especially for the several thousand Jews of northern Castile who had to make their way on foot across the border into Portugal. [2] Many of the Jewish exiles of 1492 returned from Portugal and North Africa in that year and in 1493, as well as later years, to be baptized and live again in Spain. Fernando and Isabel permitted these conversos to keep Hebrew and Arabic books as long as they were not about the Jewish law or glosses and commentaries to the Bible, or, specifically mentioned, the Talmud or prayer books. A Jew of Borja who returned after the Expulsion and converted to Christianity reported that a Jewish cofradía (religious brotherhood) of that town had left 55 books valued at 4,000 jaqueses, but he wanted no part of the books because he had converted.[3]

Portugal

Isaac Ibn Faraj, one of the exiles from Portugal, reported that the king had ordered that all the books which the Jews had brought with them from Spain were to be collected and burned. Nonetheless, not all books were, in fact, burned. Another source reveals that long after the Jews were expelled from Portugal, the king of Morocco sent Jewish delegates there, one of whom was a qabalist who asked permission to see a famous biblical manuscript brought by the Jews from Spain, and this manuscript was among the books seized by the king and kept in a “synagogue filled with books.”[4]

Levi Ibn Shem Tov and his two brothers, apparently the great-grandsons of the Spanish qabalist Shem Tov b. Joseph (not, as usually stated, Shem Tov b. Shem Tov), advised King Manoel to seize all the Jewish books. Their intention had also been to burn the Sefer ha-emunot of their great-grandfather, because of his criticism of Maimonides, but they became afraid because of an order of the king not to burn any Jewish books, and therefore they hid the book in a synagogue in Lisbon. When the Jews were expelled from Portugal, those Jews who had been appointed by the king to search out and seize all books discovered this hidden manuscript and brought it, along with portions of the yet-unpublished Zohar, to Turkey (these men were Moses Zarco, Isaac Barjilun, Moses Mindeh [?], and apparently Solomon Ibn Verga, author of the semi-fictitious chronicle Shevet Yehudah). This undeniably accurate testimony appears to contradict the eyewitness account of Ibn Faraj mentioned earlier. Either he was confused, or else the king issued contradictory orders at different times.[5]

Italy

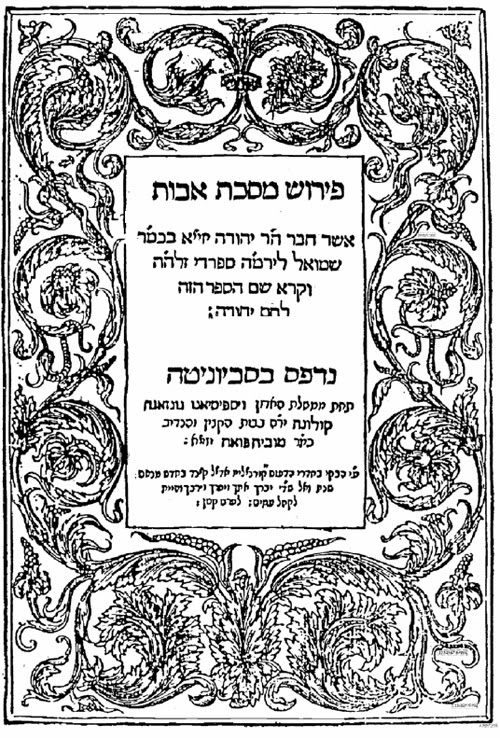

In 1533 the Talmud was, once again, condemned to the flames in Italy, and with it also legal codes or summaries derived from the Talmud. As in Spain and Portugal, censorship of all Jewish books was under the jurisdiction of the Inquisition. In 1568 a second, more sweeping, destruction of Hebrew books was carried out. Not only Jews, but even Christians, who dared to print such prohibited Hebrew books were subject to punishment, such as exile in the case of Jews, or loss of license in the case of Christians. Rabbi Judah Lerma, perhaps the first Sefardic author who so declared himself, proudly, on the title page of his book, published his Lehem Yehudah, a commentary on Avot, in Sabionetta (1554).

In his introduction to the work, printed by Tuviah Foa, he states he had already had it printed in the previous year, but the decree consigning to the flames the Talmud and Jacob Ibn Habib’s famous anthology of the talmudic agadah had also caught his work, as well as the laws of Isaac al-Fasi, and the entire edition of 1500 copies of his book (a very large printing for the time) was burned. (Later he was able to purchase, at great cost, one copy which had been saved by Gentiles; if that copy had survived until today it would certainly be the rarest Hebrew book in the world.)

David Conforte (1618-1685) also briefly cited this introduction, noting that his maternal grandfather Yequtiel Azuz, a grammarian and qabalist who lived in Italy, lost his own copy of the Talmud in the burning which took place in the same year. Ironically, a later Judah Lerma, a rabbi in Belgrade, an apparent descendant of Judah Lerma, also lost most of the edition of his own responsa in a fire in that city (ca.1650), but at least that was a natural disaster. [6]

Shortly after the burning of the Talmud, Rabbi Samuel de Medina of Salonica, who already had news of the event, wrote that because of this, and the general religious persecution taking place in Italy, any Jew who remains there “without doubt shows no fear for his soul or his Torah,” for were it not so how would a Jew dare remain there? Furthermore, he wrote, it is impossible even to study Torah (Talmud) in Italy. Therefore, all Italian Jews should come to the Ottoman empire to live, since “the soul and body and also possessions are immeasurably safer in this kingdom.”[7]

Marranos and Censorship

In addition to this loss of manuscripts and books, the invention of printing brought with it a new fear, that of censorship. Much has been written about the censorship of Hebrew books at the hands of Christians, but less known is the “internal” censorship practiced particularly by “Marranos,” or descendants of those who converted to Christianity and then decided to become Jews. They often brought with them the inherited Catholic condemnation of people (excommunication, as in the case of Spinoza) and of books which they judged to be offensive.

Amsterdam. Some descendants of Portuguese Jews who had converted to Christianity eventually fled to Italy, where they decided to go to Amsterdam and convert to Judaism. One of the most famous of these was Miguel (Daniel Levi) de Barrios (1635-1701), who was one of the greatest literary figures of the time. He was publicly condemned for visiting “a land of idolatry” (Spain, or Portugal?) and for public profanation of the Sabbath. The publication of his allegorical masterpiece Coro de las musas (1672) was immediately condemned by the Mahamad (official council of the Jewish community). Even more serious was the reaction to his next work, Harmonia del mundo (1674), which was prohibited altogether and was denounced by the famous Rabbi Jacob Sasportas (who led the campaign against Shabetai Sevi) as “converting our Torah into a profane book, making of it a poetic version.” In 1690 his Arbol de vidas [sic; the error is perhaps due to an unconscious influence of the Hebrew plural hayim, “life”) appeared and was also immediately condemned, or more specifically the “conclusions” he appended to it were condemned. The Mahamad prohibited anyone possessing, selling or giving a copy of it to any other Jew on pain of excommunication. Finally, in 1697 he was again condemned for writing a letter to the magistrate of Hamburg which the Mahamad considered potentially injurious to the “Nation” (the community). Thus did the “Nation” honor one of its greatest writers. [8]

Germany. Already in the latter part of the sixteenth century we find mention of some few Portuguese “new Christian” merchants in Germany. One of the most important cities where these “Marranos” settled was Hamburg. In 1612 a five-year contract was made by the Senate of Hamburg with the “Portuguese Nation” (the Marranos) granting them freedom of trade and residence, but stipulating that no synagogue was to be maintained nor were they to “offend” the Christian religion. They could bury their dead in Altona or wherever they chose. The population was not to exceed 150 individuals. In 1617 the original contract with the Senate was renewed for another five years, in return for a payment of 2,000 marks, and again in 1623.[9]

Having grown up and been educated in such an atmosphere of fear and intimidation in Portugal, it is perhaps not surprising that Marranos, new converts to Judaism, applied hardly less intolerant measures of censorship within their own communities. For example, the “offensive” books of Manuel de Pina (a Jew) were ordered burned by the Sefardic communities of Amsterdam and of Hamburg (1656). In 1666 the Mahamad of Hamburg ordered copies of Moses Gideon Abudiente’s book Fin de los dias (“End of days”) sealed and locked in the community safe “until the time for which we hope arrives;” i.e., until the “end of days”! Furthermore, it was decided to impose a fine on any member of the community who kept a book which did not have the “Imprimatur” (!) of the Mahamad.[10]

England. In 1664 the Saar Asamaim (Sha ar ha-Shamayim) synagogue enacted the Escamot or Acuerdos adapted from those of Amsterdam. In turn, these ordinances were adopted by the communities of Recife (Brazil), Curaçao and New Amsterdam (New York). These enactments included a prohibition on the printing of books in Hebrew, Ladino, or any other language without the approval of the Mahamad.[11]

Italy. Fear of the Inquisition and of general problems which could be caused by negative references to Spain led to Jewish censorship even of the liturgy. Thus, the Sefardic mahzor printed in Venice in 1519 (second edition in 1524) already omitted the Spanish Hebrew lamentations referring to the attacks on the Jewish communities in 1391;[12] nor was any reference to the Expulsion permitted. In a prayer book, Imrey Na’im, published probably by Menasseh b. Israel (Amsterdam, 1628-30), appeared a poem which seems to be a general lamentation on Jewish suffering, but which Bernstein has shown is found in its original form in the prayer book for fasts, Arba’ah Ta’aniyot, printed in Venice in 1671, when there was no longer fear of an Inquisition. There, in fact, the prayer is a lamentation on the Expulsion.[13]

No doubt there are other examples of Jewish “self-censorship” in this period, but it is hoped that this brief introduction will serve to arouse interest in the topic.

Notes

[1] For information on early printing, and fragments of talmudic tractates, in Spain and Portugal, see my Dictionary of Iberian Jewish and Converso Authors (Madrid, Salamanca, 2007), pp. 39-40 (Nos. 35-37), pp. 56-58 (Nos. 86-101. The second edition of the Torah commentary of Moses b. Nahman (“Nahmanides”) was also printed at Lisbon, 1489.

[2] On censorship of Hebrew books in Spain already before the Inquisition, books owned by conversos, etc., see my Conversos, Inquisition, and the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain (Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1995; revised and updated paper ed., 2002), index; seeespecially p. 103, Jews called upon to examine Heb. books owned by conversos, and p. 242.

[3] Miguel Angel Motis Dolader, Expulsión de los judíos del reino de Aragón (Zaragoza, 1990), vol. 2, pp. 338-39.

[4] Elijah Capsali, Seder Eliyahu zuta, ed. Aryeh Shmuelevitz, Shlomo Simonsohn, and MeirBenayahu (Jerusalem, 1975-83), vol.1, p. 238.

[5] Text edited from Ms. by Meir Benayahu in Sefunot 11 [1971-78]: 261, and cf. there p. 234 onLevi Ibn Shem Tov, and p. 246 on Isaac Barjilun, or Barceloni. He and Moses Zarco may have been the important tailors in Portugal, the former the court tailor of João II, mentioned in Maria Jose Pimenta Ferres Tavares, Os judeus em Portugal no século XV (Lisbon,1982-84) vol. 1, pp. 156, 252, 361 and 301. On the Jewish official Judas Barceloni at that time, see ibid. vol. 2, p. 669.

[6] See Abraham Yaari, Meqahrei sefer (Jerusalem, 1958), p. 360, citing the full introduction of Judah Lerma’s commentary; Conforte, Qore ha-dorot (Berlin, 1846; photo rpt. Jerusalem, 1969), pp. 40b and 51b. As have virtually all scholars, Yaari ignored Conforte, and therefore did not mention the second Judah Lerma in his own discussion of books lost in fires (p. 47 ff.).

[7] She’elot u-teshuvot, hoshen mishpat (Salonica, 1595), No. 303; cited in Meir Benayahu, ha-Yahasim she-vein yehudei Yavan le-yehudei Italiah (Tel-Aviv, 1980), pp. 93-94 (my translation);see there also for other important material relating to this and to censorship, pp. 95-97.

[8] See the excerpt of Arbol de la vida in Barrios, Poesía religiosa, ed. Kenneth R. Scholberg (Madrid [Ohio State University Press], s.a. [1962]), p. 99.

[9] Alfredo Cassuto, “Contribução para a história dos judeus portugueses em Hamburg,” Biblos (Coimbra University) 9 (1933): 661; see also Hermann Kellenbenz, Sephardim an der unteren Elbe (Wiesbaden, 1958 [ Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtsschaftsgeschichte No. 40] ), pp. 31-32.

[10] “Protocols” (of the Sefardic of Hamburg); summarized in Jahrbuch der jüdisch- literarischen Gesellschaft 6 (1909); 7 (1909); 10 (1915); 11 (1916); see 7: 183; 11: 27-28.

[11] Miriam Bodian, “The Escamot of the Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Community of London, 1664,” Michael 9 (1985): 23-24, No. 30 (text; in [barbaric] Spanish). Earlier editions and studies are Lionel Barnett, ed., El libro de acuerdos (Oxford, 1931), and N. Laski, The Laws and Charities of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation of London (1952).

[12] For these, see the translations in the journal Iberia Judaica 3 (2011): 77-113.

[13] Simon Bernstein, ed. #Al naharot Sefarad (Tel-Aviv, 1956), pp. 23, 25, 26-28.