‘Masa’ot Yerushalayim’ and the ‘Sabba Kaddisha’ R. Shlomo Eliezer Alfandari

By: Moshe Maimon

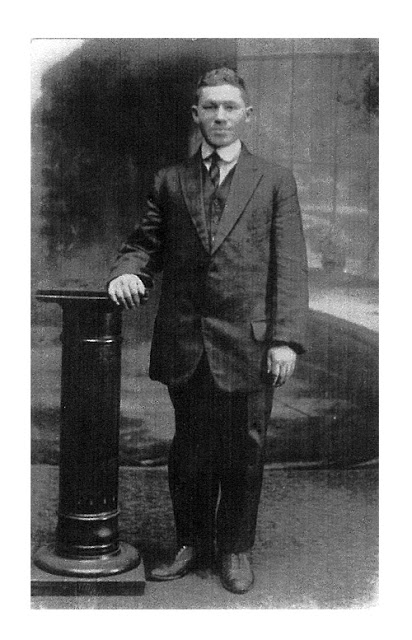

One of the greatest and most unique Torah scholars, Sephardic or otherwise, of the past 100 years was R. Shlomo Eliezer Alfandari . His life spanned about a century

[1] and his prolific rabbinic career included stints in Istanbul, Damascus, Safed and Jerusalem. Besides for being an outstanding scholar with a near-photographic memory he was also extremely diligent and was a prodigious writer of responsa and novellae. Additionally, he was renowned as an independent thinker and outspoken critic of many of the societal norms prevalent around him including Zionism and modernity, and he had little tolerance for those who he felt had strayed from the torah-true path.

[2] This quality earned him many admirers and not a few adversaries, but all admitted that R. Shlomo Eliezer’s sole motivation was the truth and he did nothing for personal gain. Indeed, despite his considerable means, he lived a life of asceticism and completely shunned any form of publicity.

Amongst his native Sephardic brethren he was known as ‘Chacham Mercado Alfandari’.

[3] This unusual-sounding surname; ‘Mercado’, meaning ‘purchased’ in Ladino, was somewhat common in his native Turkey and was indicative of the fact that it’s bearer had undergone a symbolic ceremony in his youth whereby he was ‘sold’ and redeemed. This practice is mentioned in

Sefer Hasidim (#245) and was widespread in Sephardic lands.

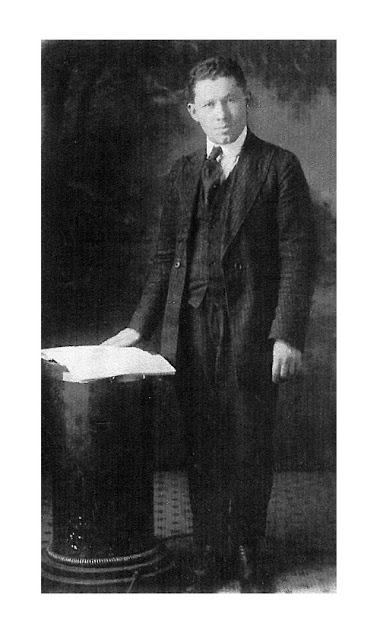

[4] My Great-uncle, Sam Bension Maimon, himself a Turkish native, in his book

The Beauty of Sephardic life (p. 188) has this to say about that interesting custom:

This practice of “purchase,” was followed by a family that was blessed with a newborn baby, but had previously suffered the loss of an infant before the new arrival. In order to ensure the life of the

muevo nasido (newborn baby), they would go through a formality in which a relative or a friend would “purchase” this baby from the parents, thus transferring ownership. This was done to outsmart the evil spirits and ward off their fatal hold on this family’s offspring that was marked for a fatal accident. So, if it was a boy, he was called

Mercado; or if it was a girl, she was called

Mercada.

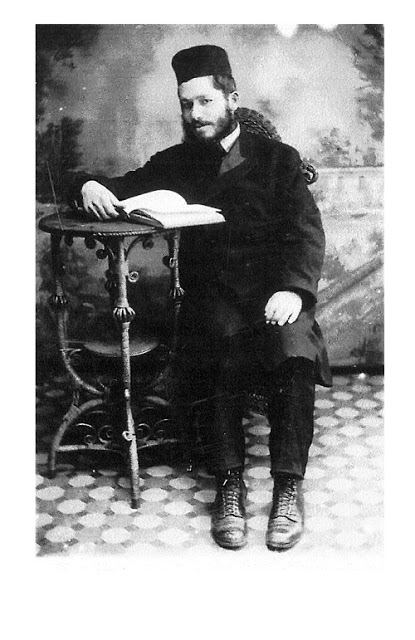

[5]Today, however, he is more popularly known as ‘the Sabba Kaddisha’ which was the title bequeathed upon him by the Minchas Elazar of Munkacz; R. Chaim Elazar Shapira, who was largely responsible for bringing this sage to the attention of the greater public especially in Europe among the Ashkenazim. This also was used as the title of his response – שו”ת הסבא קדישא. In a sense, the Munkaczer was also responsible for shaping the perception that many people have of R. Alfandari, as his perspective as detailed in his writings and in Masa’ot Yerushalayim, is the lens through which many see the Sabba Kaddisha.

The Munkaczer, after hearing about this extraordinary personality almost completely coincidentally, gradually became convinced that this sage was the ‘Holy elder’ or Sabba Kaddisha of the generation. According to a personal Hassidic tradition he had, the Holy Elder of every generation was capable of bringing the Messiah. This is what drew this great Hassidic leader, born and bred in Ashkenazic/Hassidic Hungary to R. Alfandari, although from a distance it might have seemed that the two made strange bedfellows. R. Alfandari, for his part, was delighted to make the acquaintance of an important Torah leader who shared his extreme views on Zionism and modernity.

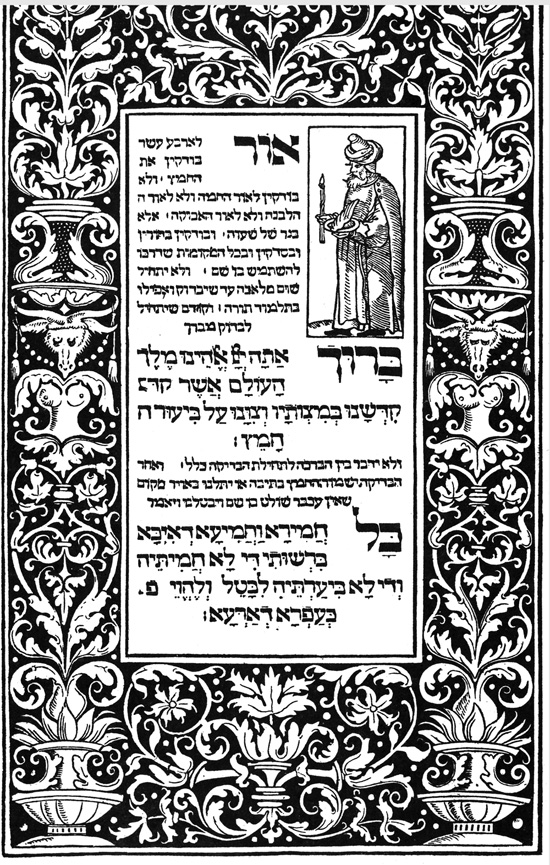

Masa’ot Yerushalayim; Journey To Jerusalem: A review

There are various sources which provide biographical information on this unique sage,

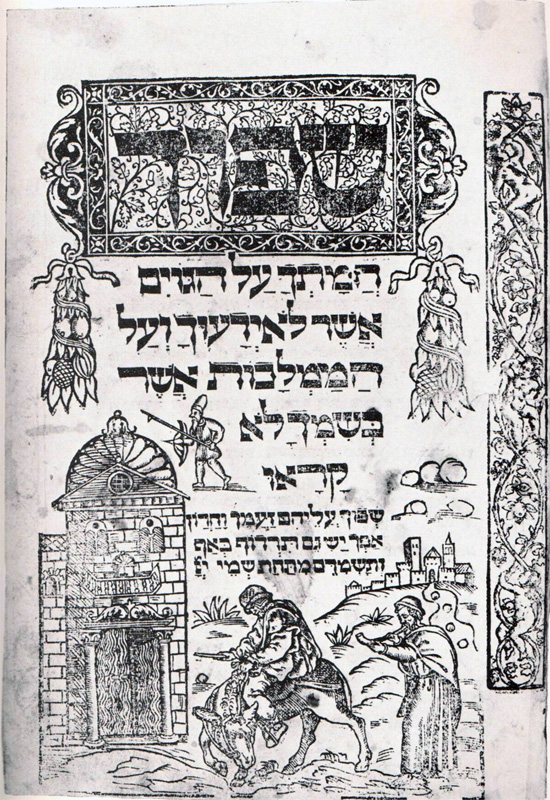

[6] but predominant among them is the detailed account of the Munkaczer Rebbe’s trip to meet R. Alfandari in the late spring of 1930 shortly before the latter’s passing. This account was written by a follower of the Rebbe, who accompanied him on his trip, by the name of R. Moshe Goldstein. The book, entitled

Masa’ot Yerushalayim which also contains a biographical section on R. Alfandari

[7] was first published 1931 in Munkacz and has been published many times since. This monumental meeting between east and west is a most interesting narrative and in addition to providing insight into the lives of these great scholars, it also allows for a view of pre-war Israel which is the backdrop for this meeting.

The book was recently translated into English by Artscroll (in 2009) and is called Journey to Jerusalem. It is this last work which I will focus on. Unfortunately, instead of adhering to their usual high standard and putting in the type of quality effort they have come to be known for into producing a professional edition of this classic, I found it to be lacking in many basic areas. First off, it is essentially just a simple translation from the original, complete with the archaic syntax such as ‘the Holy Rebbe’, ‘the Holy shul’, etc. Generally speaking, such prose, although sounding fine in Rabbinic Hebrew, nevertheless grates on the ears when rendered into English.

Additionally, the ’famed’ Artscroll system of transliteration

[8] was dropped in the case of this book, instead they adopted in many instances

the Hungarian Hasidic mode of pronunciation. Understandably, this can be accepted when mentioning the Minchas Elazar who was known to his Hasidim as the Minchas

Eluzar; but what justification is there, on the other hand, for spelling out Rabbi

Eluzar son of Rabbi Shimon (p. 136) and Rabbi

Eluzar Azikri (p. 157)?

In one instance (p. 205) they transliterated the Hebrew spelling of the Isle of Rhodes (רודיס) and thereby refer to “…The great Rabbi Rephael Yitzchak Yisrael, rav of Rudis (!)”.

In one case a faulty translation of the original completely corrupts the meaning of the sentence such as when discussing the origin of the famous Abohab Synagogue in Safed the author writes parenthetically:

אינו נודע אם זהו בעהמח”ס מנורת המאור או זקינו.

In English they got it backwards and wrote (p. 148):

It is unclear whether it was he or his grandfather who authored the Menoras Hamaor.

So much for style, but when it comes to content there are also quite a few editorial blunders such as when they refer to the Maharit (= Moreinu Harav Yosef diTrani) as Rabbi Yitzchak (!) of Trani (p. 204). One particularly egregious oversight can be found in the following paragraph (from p. 142 – 143):

The story is told in the holy Rabbi Shlomo ibn Gabirol’s accounts of his travels in Eretz Yisroel that because of Rabbi Alkabetz’s great wisdom, the gentiles envied him, and an Arab killed him and buried him under a tree in his garden. When the tree bore fruit early, people investigated. The crime was discovered, and the murderer was hanged on that very tree. This story is recorded in the holy work Kav Hayashar (chapter 86) about Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz.

Besides for the obvious problem with this story being that R. Shlomo Ibn Gabirol preceeded R. Alkabetz by 500 years, there are two contradictory sources given for this tale, namely the supposed ‘accounts of R. Ibn Gabirol’s travels’ (a non-existent work) and Kav Hayashar. A quick check with the Hebrew Edition will reveal the source of this error. Here is the original:

ולפלא, כי המעשה שהביאו בספרי תיירי ארץ הקודש מהקדוש מה״ר שלמה בן גבירול שמרוב חכמתו נתקנאו בו אומות העולם, וישמעאל אחד הרגו והטמינו תחת אילן בגן שלו, ועל ידי שהתאנה חנטה פגיה קודם זמנה חקרו, ואכן נודע הדבר ונתלה הרוצח על אותו אילן, מובא בספר הקדוש קב הישר (פרק פ״ו) על מה״ר שלמה אלקבץ ז״ל, יעיין שם.

What he is saying is that he was amazed to find that different accounts of tourists’ travels in Israel record a story supposedly about R. Shlomo Ibn Gabirol, while in Kav Hayashar it is reported to have happened to R. Shlomo Alkabetz. This is indeed an important bibliographical point, but In truth this legend is actually quoted in

Shalshelet hakaballah regarding Ibn Gabirol

[9] and although the authenticity of this sefer is often questioned, there can be no doubt that the legend predates R. Shlomo Alkabetz and indeed no contemporary sources indicate that R. Alkabetz had anything but a peaceful end. Even though all early prints of

Kav Hayashar that I have checked say R. Shlomo Alkabetz, the context leaves no doubt that it is a mistake and should read Ibn Gabirol.

[10]Censorship and political correctness in Masa’ot Yerushalayim

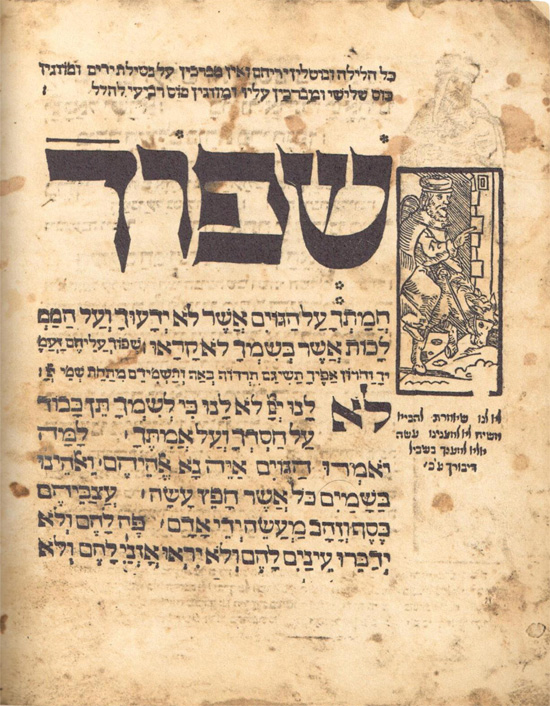

It is clear that the English edition is a translation from the latest Hebrew Edition published in 2003

[11] by Emes publishing ltd. (the official publishing house of the Munkacz Hasidim in Brooklyn).

[12] This addition is somewhat different from the first edition and I am not sure on what basis these changes were made. In addition to the footnotes which were actually parenthetical remarks included in the text in the original they have added numerous footnotes expanding and cross-referencing the material

[13] and there is no differentiation made between the original footnotes and the later ones. There are also various differences in the text itself. For instance the original edition when describing the Grave of R. Haim ibn Attar, (the author of Ohr Hachaim) the first edition (p.25b) adds:

‘סמוך למנוחת האוה”ח הקדוש שם ג”כ מנוחת אשתו ושתי יבמות שהיו לו לנשים’

The 2003 edition is less shocking in it’s revelation by stating instead:

‘סמוך למנוחת האור החיים הקדוש שם גם כן מנוחת שתי נשיו‘

This is also the version found in the English translation and if memory serves correct, contemporary restorations at the actual gravesite reflect the veracity of the later edition. In fact, this may be the reason they took the initiative, justified or not, to change the text.

[14]On another occasion the altering of the text was clearly intended to avoid possible fallout with today’s Yeshiva adherents. I refer you to the passage in the first edition (p.87b-88a) which recounts how certain members of the Hareidi Rabbis of Jerusalem approached the Munkaczer Rebbe in an attempt to find a solution to the problem of the negative effect the recently established Hebroner yeshiva was having on native Jerusalmite youth on account of the former’s modern style of dress.

[15] The Rebbe hastened to consult with R. Alfandari who wisely advised him not to make a commotion over it as such a fuss would only have negative ‘political results’. It reads like this:

בהיות רבנו שליט”א בתוככי ירושלים באו אליו גדולים חקרי לב מהרבנים החרדים שם ליהנות ממנו עצה ותושי’ כדת מה לעשות ע”ד ישיבת סלאבאדקע שהיתה מלפנים בחברון ואחר הפרעות והשחיטות ר”ל נעתקו משם וקבעו ישיבתם בירושלים והמה רובם ככולם (אם כי למדנים הם) הולכי קצוצי פאות וזקן ומגדלי בלורית ורגילים לזה ממדינתם ובהיותם בחברון שאין שם ישוב חסידים מהאשכנזים כ”כ לא הזיקו לאחרים משא”כ פה בקרתא דשופריא עיר מלאה חכמים חסידי עליון ירעו וישחיתו לנו ולבנינו ותלמידי ישיבתנו שילמדו מהם ח”ו בדמותם כצלמם.

רבנו בשמעו את כל התלאה הזאת הלך להתייעץ עם הסבא קדישא הרב מהרש”א אם להרעיש עליהם כעת אחרי שנמלטו על נפשם מהפראים וכו’. והוא השיב בחכמת שלמ”ה אשר בקרבו כי יש לחוש בעודם בחמימות מהרוגי חברון שנשחטו גם מתלמידי ישיבתם (ובתוכם יראי ה’ הי”ד) ואם ירעישו עליהם יכנסו תחת כנפי אותו האיש קוק וכל משרד הרבנות הציונית שר”י ועי”ז יתרבה חילם עי ישיבת סלאבאדקי מפורסמת בעולם והראש מתיבתא שלהם מפורסם ללמדן ע”כ שוא”ת עדיף כעת…

וכשאני לעצמי כשבאו תלמידי סלאבאדקא לביתי לדבר דברי תורה, וראיתים בלי זקן ופיאות ומגדלי בלורית, אמרתי להם על הכתוב (שיר השירים ב, יד) הראיני את מראיך (צלם אלקים על פי התורה. ואחר כך) השמיעיני את קולך בדברי תורה. אבל כשהוא ההיפך לא אדבר עמכם, ודחיתים כי הם באמת מחריבי קרתא קדישא. וכן יעשה גם הדר״ת להזהיר לאנשי שלומו ויראי אלקים להתרחק מישיבתם, אבל לא לצאת עתה בקול רעש מטעם הנ”ל עכתד”ה.

The 2003 edition censors this passage and simply writes:

בהיות רבינו שליט״א בתוככי ירושלים באו אליו גדולים חקרי לב מהרבנים החרדים שם ליהנות ממנו עצה ותושיה כדת מה לעשות על דבר פרצה מיוחדת שנפרצה בעיר ה׳. ושאל רבנו להסבא קדישא מה לעשות במחיצת כרם בית ישראל שנפרצה. וענה לו הסבא קדישא כי יש לחוש וכו’ על כן שב ואל תעשה עדיף כעת…

וכן סיפר הסבא קדיש אל רבינו כשבאו תלמידי ישיבה מסוימת לביתי לדבר דברי תורה, וראיתים בלי זקן ופיאות ומגדלי בלורית, אמרתי להם על הכתוב (שיר השירים ב, יד) הראיני את מראיך (צלם אלקים על פי התורה. ואחר כך) השמיעיני את קולך בדברי תורה. אבל כשהוא ההיפך לא אדבר עמכם, ודחיתים כי הם באמת מחריבי קרתא קדישא. וכן יעשה גם הדר״ת להזהיר לאנשי שלומו ויראי אלקים להתרחק מהם, אבל לא לצאת עתה בקול רעש, עד כאן תורף דבריו הקדושים.

There is no reason to suspect that this was done to protect the identity of R. Kook, because this edition shows little sympathy for R. Kook, in fact in the preceding paragraphs dealing with R. Alfandari’s opposition to R. Kook, the Chief Rabbinate

[16], and even to Agudath Israel, nothing is omitted and the material is buttressed with lengthy footnotes detailing all the letters written by various Rabbis opposing Zionism in general and the Chief Rabbinate in particular. It is obvious that sensitivities for the Slabodka Yeshiva are at the root of this censorship. This is also why the next passage (from p. 88a), which I am loath to reproduce here, detailing R. Alfandari’s assessment of R. M.M. Epstein and R. Kook is also omitted in the 2003 edition.

Needless to say the English edition not only follows lead of the 2003 edition in censoring the Slabodka passages but also omits all of the anti R. Kook passages such as this one, from p. 229 in the 2003 edition:

כשבאו אליו אח”כ אנשים גם רבנים או אדמורי״ם שבאו לא”י, ושמע שהיו אצל ׳קוק׳ רב חראשי של המשרד חציונית והחפשים, לא אבה לקבלם להכניסם לביתו, ואמר הלא כבר היה אצל קוק

[17] ומה יחפצו ממני, ומדוע אתם פוסחים על שתי חסעיפים.

Gone too are the following statements regarding Agudath Israel attributed to R. Alfandari, and with them a possible window into the special relationship he shared with the Munkaczer:

פעם אחד שאלו אותו לחוות דעתו בענין האגודה. והשיב שאין חילוק בין הציונים והמזרחים והאגודים רק בשמא, וחוט המקיף את כולם הוא הכסף והשתררות ולא כבוד שמים. על כן היה אוהב מאוד כששמע מצדיק ואדמו״ר אשר לא כרע לבעל לשום אחת מהמפלגות וכתות הנזכרים לעיל, ואדרבה מוחה בהם ומקנא קנאת ה׳ צבאות. ואמר כי מדה זו אהוב לו מן הכל ועולה על כולנה יותר מבקיאות התורה והפלגה בחסידות וזכות אבות, אם כי רב הוא.

Understandably, the English speaking audience this book is intended for is not as virulently anti-Zionist as the Munkacz/Satmar Hasidic base that the Hebrew edition was intended for and certainly wouldn’t countenance any anti-Agudah sentiments and therefore excised the more extreme passages from its translation. It is therefore all the more surprising that the following passage got by the careful eye of the censor and made it into the English edition on P. 178:

We found out that the main reason they did not keep their word was because they were afraid of their rabbi and leader, Yaakov Maier, a member of the official rabbinate, which the Sabba Kaddisha strenuously opposed. Immediately after the Sabba Kaddisha’s demise the zealous Torah scholars of Jerusalem warned Yaakov Maier not to come eulogize him.

Obviously they did not realize that despite R. Yaakov Meir’s affiliation with the Rabbinate as the Sephardic Rishon L’zion, nevertheless he was widely respected by virtually all segments of orthodox Jewry

[18]. Indeed another popular Artscroll biography actually lauds R. Yaakov Meir for forging a close connection with Jerusalem’s Ultra-Orthodox Eidah Hachareidit and working together with them on various occasions.

[19] Most likely, the American proofreader did not know who this famous Israeli-Sephardic personality was and thus allowed this disrespectful passage though.

In conclusion

The biographical information available on R. Alfandari is sparse, and precious little of it pertains to the bulk of his life before his move to Jerusalem in his final decade. There is certainly much more to the picture we could gain from a fuller biography of his life, also taking into perspective the vastly different milieu that he sprouted from. Yet, the detailed picture we have from the period of the Munkaczer’s visit certainly is an accurate portrayal of at least one dimension of his great personality. As I have demonstrated, the reader is best served consulting the original version where possible to obtain a more complete and accurate snapshot of this historic encounter.

In the case of R. Alfandari, this sort of contest for understanding and presenting his legacy is a testament to his greatness, his broad appeal, and to his own multi-faceted personality. He is certainly worthy of further in-depth study, and a full-length professional biography would certainly give us much to learn from and be inspired. However, this will only be true if the study is free of the constraints of bias and preconceived notions.