Soloveitchick’s Act of Selfless Heroism, 1785

A few weeks ago, on the Courland coast (a bay of the Baltic Sea), a certain Russian courier on route to Würtemberg burst before the sleigh of a Polish Jew. Suddenly the ice broke under his horse and the abyss threatened to swallow horse and rider. The Jew saw this and heard the Christian wailing, he jumped in and saved him at the risk of his own life. The courier then pulled out his bag to reward the Jew, but he turned down the money, and asked for nothing more than that every poor Jew that the rescued man would see in danger he would take under his wing. This Jew, Abraham Isaac’s son, is called Soloveitchick and is a native of Kovno in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

מנהג אמירת ‘שלש-עשרה מידות’ בהוצאת ספר תורה בימים נוראים ובשלש רגלים ובפרט כשחל בשבת

נוראים ובשלש רגלים ובפרט כשחל בשבת

אישית[1].

בליל יום הכיפורים תשס”ה, שבאותה שנה חל בשבת, שמעתי באזני מפי הגרי”ש

אלישיב זצוק”ל, שענה לשואל אחד שאין לאמרם בשבת, אע”פ שהשואל הסתייע

מלוח ארץ ישראל לרי”מ טוקצ’ינסקי שיש לאומרם. אחר כך סיפר השואל לנוכחים

שמפרסמים פסקים בשם הרב שאינם נכונים כלל וכלל.

לא נכח הגרי”ש בבית הכנסת, ובהוצאת ספר תורה פתח החזן באמירת ‘שלש-עשרה

מידות’. קם אחד המתפללים וגער בו בקול: ‘אתמול קבע הרב שליט”א שאין לאומרם

בשבת!’ נעמד לעומתו נאמנו של הגרי”ש ר’ יוסף אפרתי, וסיפר כי אמש לאחר שאלת

השואל, ישב הרב בביתו על המדוכה בדק ומצא כי בספר ‘מטה אפרים’ פסק לאומרו, וסמך

עליו. ולפיכך יש לאומרו גם ביומא הדין שחל בשבת.

שמפרסמים פסקי-שווא בשם הרב לא נכח שם, וגם הוא לא זכה לשמוע משנה אחרונה של הרב

בענין זה.

שהעליתי במצודתי:

תצ”ה, חלק ימים נוראים, פרק א עמ’ ט, נאמר: “והרב זצ”ל כתב שכל המתענה

בחדש הזה שיאמר ביום שמוציאים בו ספר תורה בעת פתיחת ההיכל הי”ג

מידות ג’ פעמים”[2].

ממקורות שונים ואין לו מדיליה כמעט כלום. דברי האריז”ל מופיעים כבר ב’שלחן

ערוך של האריז”ל’, שנדפס לראשונה בקרקא ת”ך[3]. ומשם

העתיק זאת ר’ יחיאל מיכל עפשטיין לספרו ‘קיצור של”ה’, שנדפס לראשונה בשנת

תמ”א[4]

[דפוס ווארשא תרל”ט, דף עה ע”א]. וכ”כ ר’ בנימין בעל שם, בספרו ‘שם

טוב קטן’ שנדפס לראשונה בשנת תס”ו[5], וגם

בספרו ‘אמתחת בנימין’ שנדפס לראשונה בשנת תע”ו[6]. כל

החיבורים הללו נדפסו קודם ‘חמדת ימים’.

לר’ יעקב צמח, שנדפס לראשונה באמשטרדם שנת תע”ב[7], מצינו:

“מצאתי כתוב בסידור של מורי ז”ל בדפוס כמנהג האשכנזים, והיה כתוב בו אחר

ר”ח אלול מכתיבת מורי ז”ל: שכשהאדם עושה תענית, שישאל מן השי”ת

שיתן לו כפרה וחיים ובנים לעבודתו יתברך, וזהו בהוצאת ס”ת, ויאמר אז

הי”ג מדות רחמים שלש פעמים, ואני תפלתי שלשה פעמים…”. ר’ יעקב צמח

הוסיף שם: “יש סמך לזה בזוהר יתרו קכו וגם בעין יעקב ר”ה סי’ יג

בפירושו”[8].

אליהו שפירא ב’אליה רבה’ (סי’ תקפא ס”ק א) שנדפס לראשונה לאחר פטירתו בשנת

תקי”ז בשם ר’ יעקב צמח[9].

מי שמתענה בחודש אלול ראוי שיאמר י”ג מידות בשעת הוצאת ס”ת[10].

בחיבורו הידוע ‘שערי ציון’ (נדפס לראשונה בפראג תכ”ב ובשנית באמשטרדם

תל”א): “בראש השנה וביוה”כ בשעת הוצאת ס”ת יאמר י”ג מדות

ג”פ, ואח”כ יאמר זאת התפילה, רבונו של עולם מלא משאלותי לטובה…”[11].

שבועות יקרא ג’ פעמים י”ג מדות ואח”כ יאמר תפלה זו רבש”ע מלא כל

משאלתי…”. העתיקו ר’ בנימין בעל שם בספרו ‘אמתחת בנימין’ שנדפס לראשונה

בשנת תע”ו.

אליהו הכהן שנפטר בשנת תפ”ט כתב שיש לומר בר”ה, ביו”כ, בסוכות

ובשבועות, י”ג מידות ג”פ ואחר כך יאמר רבש”ע[12].

אבל יש לציין שחיבור זה נדפס לראשונה בשנת תצ”ז באיזמיר.

“שלש עשרה מדות ורבון העולם לי”ט ור”ה וי”כ אינם בשום סדור

כ”י ולא בדפוסים ישנים אבל הם נעתקות אל הסדורים החדשים מס’ שערי ציון שער

ג”[13]. וכ”כ בסידור אזור

אליהו עי”ש[14].

ר’ ישכר בער כתב בספר ‘מעשה רב’, אות קסד: “בשעת הוצאת ס”ת אין

אומרים רק בריך שמיה ולא שום רבש”ע וי”ג מידות“[15].

ונכפל באות רו, בהלכות ימים נוראים: “וכן אין אומרים י”ג מדות בהוצאת

ס”ת”. בין בשבת בין בחול.

כנראה נהגו לאמרו, וכמו שכתב ר’ יעקב כהנא: “לי”ג מדות… והנה חזינן…

ויש מקומות אשר כל ימי אלול עד אחר יו”כ אומרים אותו בכל יום, ויש מקומות

שאומרים אותו בכל יום ב’ וה’ ויש מקומות שאומרים אותו בכל יום כל השנה ולא משגחו

וטעמא מיהא בעי…”[16].

קהלת’: “והוא מנהג שלא מצאתיו בפוסקים ואין נכון בעיני לאמר י”ג מדות

בראש השנה, כי לא תיקנו לאמרן בתפילות ר”ה ולא בפיוטיו, אך יעב”ץ כתב המנהג

על פי האר”י ואין משיבין את הארי, אבל לא כתב דבר שיאמר ג’ פעמים כי הוא נגד

הדין לדעתי כי פסוקי שבחים גדולים כי”ג מדות אסור לכפלם”[17].

‘שו”ת בנין ציון’ שאלה שנשאל: “לא ידעתי על מה נסמך המנהג לומר בראש

השנה ויוה”כ וי”ט בשעת הוצאת הס”ת ג’ פעמים י”ג מדות וג’

פעמים ואני תפלתי, הרי לפי פירוש רש”י בהא דאמרינן האומר שמע שמע הרי זה

מגונה דזה באמר מלה וכופלו אבל בשכופל הפסוק משתקין אותו, ולפי’ רב אלפס עכ”פ

הרי זה מגונה ובשניהם דהיינו בי”ג מדות וגם באני תפלתי לא שייך הטעם שכתב

רש”י בסוכה (דף ל”ח) שכופלין בהלל מאודך ולמטה כיון דכל ההלל כפול וגם

לא טעם הרשב”ם בפסחים בזה משום דאמרו ישי ודוד ושמואל ואולי רק בשמע ומודים

הוי מגונה או משתקינן מטעם דנראה כב’ רשויות אבל הכפלת שאר פסוקים שרי…”.

משיב לשאלת השואל: “נראה לי לחלק דדוקא באומר שני דברים שווים דרך תחנה ובקשה

או דרך שבח ותהלה שייך החשד דב’ רשויות, לא כן בקורא פסוקי תורה וכתובים. וראי’

לזה שהרי מצוה לחזור הפרשה שניים מקרא, וע”פ האר”י יש לכפול כל פסוק

ופסוק וקורין הפסוק שמע ישראל ב’ פעמים זה אחר זה, ואין קפידא. וכיון דמה שמזכירין

י”ג מידות אין זה דרך תחנה, דא”כ יהי’ אסור לאומרם ביום טוב אלא ע”כ

לא אומרים רק כקורא פסוק בתורה וכן בואני תפלתי, ע”כ אין בזה משום קורא שמע

וכופלו. כנלענ”ד”[18].

וילנא, כתב בספרו ‘פתחי תשובה’ ליישב קושיית השואל בדרך אחרת: “ולולא

דמסתפינא ליכנס בענינים העומדים ברומו של עולם הייתי אומר דבי”ג מדות לא שייך

כלל החשד דב’ רשיות כמו בשמע, דהענין שהיו אומרים אחד פועל טוב ואחד רע וכי”ב

מהבליהם והי”ג מדות גופיה הוא סתירה לדבריהם, דבו נכלל כל המדות והנהגות

העולם והכל ביחיד, כידוע ליודעי חן”[19].

בסידורים שיאמר אדם בר”ה וימים טובים בעת הוצאת ס”ת ג”פ י”ג

מדות ואח”כ יאמר בקשתו. ונסתפקנו איך יוכל לכפול הפסוק של י”ג מדות שיש

לחוש בזה כאשר חששו רז”ל כאומר שמע שמע ומודים ומודים. יורינו המורה לצדקה

ושכמ”ה.

אלו מדעתנו אלא רק במקום שחששו בו חז”ל שהוא בפסוק שמע ישראל ובמודים, והראיה

דכופלים כל יום פסוק ה’ מלך וכו’ וכן בעשרת ימי תשובה שמוסיפים לומר ה’ הוא האלהים

ג”כ כופלים אותו. ואין לומר התם שאני שעניית הציבור מפסקת בין קריאת החזן וכן

קריאת החזן מפסקת בין עניית הציבור, דזהו אינו, דהא אפילו היחיד כאשר מתפלל ביחיד

ג”כ כופל פסוקים ואומרם בזא”ז ועוד אעיקרא פסוק ה’ הוא האלהים הוא בעצמו

כפול שאומר ה’ הוא האלהים ה’ הוא האלהים, ונמצא דאין כאן חשש שחששו בשמע ומודים, וא”כ

ה”ה בפסוק זה של ה’ ה’ אל רחום וחנון אם יכפול ליכא חשש. והיה זה שלום ואל

שדי ה’ צבאות יעזור לי. כ”ד הקטן יחזקאל כחלי נר”ו[21].

הביא בספרו ‘ארחות חיים’ בשם שו”ת בשמים רא”ש (סימן עא) בשם רב האי

גאון, שלא לומר י”ג מידות בשבת[22]. אך

ר’ אפרים זלמן מרגליות מבראדי, בספרו ‘מטה אפרים’ (סי’ תריט, סעיף יח), הכריע

שלמרות זאת כדאי לאמרו. וכפל דבריו בספרו ‘שערי אפרים’ (שער י, סעיף ה)[23].

סעיף סד) כתב עליו: “אבל המעיין יראה שאין לסמוך על דברי הבשמים רא”ש

הנ”ל ולאו הרא”ש חתום עלה”[24].

ב, עמ’ רמ בהוספות מכ”י): “כשחל בשבת אין לאמרה”. וכ”כ ר’

חיים אלעזר שפירא[25];

ר’ שבתי ליפשיץ[26];

ר’ חיים צבי עהרענרייך[27]; ר’

ישראל הלוי ראטטענבערג בעל אור מלא[28], ר’

יוסף אליהו הענקין[29] ורי”י

קניבסקי בעל ‘קהילות יעקב’[30].

בספרו ‘אשי ישראל’ בשם הגרש”ז אויערבאך, שטוב לומר פסוקים אלו גם בשבת[34].

בשעת הוצאת ספר תורה ואפילו אם חל בשבת מצינו במנהגי בית הכנסת הגדול בק”ק

אוסטרהא: “בעת הוצאת ספר תורה בר”ה ויה”כ אומרים י”ג מדות

אפילו אם חלו בשבת…”[35].

“סיפר לי מה שראה בבית הכנסת שמה גיליון הגדול ממה שהנהיג מרן המהרש”א שם

ומהם זוכר שני דברים…”[36]. שני

הדברים שהוא מביא מופיעים ברשימת המנהגים הנ”ל, ומכאן שמייחסים מנהגים אלו למהרש”א.

לפי זה, כבר בזמן המהרש”א קיים מנהג זה של אמירת י”ג מידות בשעת הוצאת

ספר תורה. מהרש”א נפטר בשנת שצ”ב[37].

מענדיל ביבער, שעל פיהם אין להביא ראיה שכך עשו בזמן המהרש”א:

מעליך כי המקום הזה קדוש הוא, במקום הזה התפללו אבות העולם גאונים וצדיקים…

המהרש”ל זצ”ל ותלמידיו, השל”ה הקדוש ז”ל המהרש”א

ז”ל ועוד גאונים וצדיקים… המנהגים אשר הנהיגו בה הגאונים הראשונים נשארו

קודש עד היום הזה ומי האיש אשר ירהב עוז בנפשו לשנות מהמנהגים אף כחוט השערה ונקה?

ולמען לא ישכחו את המנהגים ברבות הימים כתבו כל המנהגים וסדר התפילות לחול ולשבת

וליום טוב דבר יום ביומו על לוח גדול של קלף והוא תלוי שם על אחד מן העמודים אשר

הבית נשען עליהם. הזמן אשר בו נבנתה וידי מי יסדו אותה ערפל חתולתו, ואם כי בעירנו

קוראים אותה זה זמן כביר בשם בית הכנסת של המהרש”א ולכן יאמינו רבים כי

המהרש”א בנה אותה בימיו אבל באמת לא כנים הדברים…”[38].

המנהגים דבית הכנסת הגדול בק”ק אוסטרהא שמנהג אמירת י”ג מידות היה קיים

כבר בזמן המהרש”א. אמנם רואים שנהגו לאמרו גם בר”ה ויו”כ שחל בשבת.

מטרסדורף מצינו שנהגו לומר י”ג מדות בשעת הוצאת ספר תורה אף כשחל בשבת[39].

‘קיצור הלכות המועדים‘ את שני

המנהגים[40],

אבל למעשה כתב שבר”ה שחל בשבת אין אומרים אותו ורק ביוה”כ שחל בשבת

אומרים י”ג מידות[41].

המבורגר ב’לוח מנהגי בית הכנסת לבני אשכנז’ המסונף לשנתון ‘ירושתנו’ ספר שביעי

(תשע”ד), עמ’ תז: “בהוצאת ספר תורה אומרים י”ג מידות ותפילת ‘רבון

העולם’ אף כשחל בשבת”, ואילו לגבי ר”ה שחל בשבת הוא כותב שאין אומרים י”ג

מידות ותחינת רבונו של עולם[42].

משום איסור שאלת צרכיו בשבת, כפי שהעיר ר’ יששכר תמר על המנהג המובא בשערי ציון לומר

י”ג מדות בשבת[43]. ענין

זה רחב ומסועף, ואחזור לזה בעז”ה במקום אחר, אך יש להביא חלק מדברי

הנצי”ב בזה:

המג”א שם בס”ק ע’ שאין לומר הרבון של ב”כ בשבת, ולכאורה מ”ש

שבת מיו”ט בזה… והטעם להנ”מ בין יום טוב לשבת יש בזה ב’ טעמים, הא’

משום דכבוד שבת חמיר מכבוד יום טוב, או משום שביו”ט יום הדין שהוא רה”ש

כידוע, ונ”מ ביום טוב שחל בשבת דלהטעם משום דכבוד שבת חמיר א”כ יום טוב

שחל בשבת אין לאומרו, אבל להטעם משום דיו”ט של ר”ה שהוא יום הדין יש לאומרו,

א”כ אפילו חל יום טוב בשבת ג”כ צריך לאמרו, והרמב”ם שכתב דתחינות

ליתא בשבת חוה”מ, דוקא בשבת חוה”מ, אבל יום טוב שחל בשבת יש לאומרו,

וכיון דשרי תחינות אומרים נמי הרבון, ומעתה אזדי כל הראיות שהביא המ”א

מתשובות הגאונים דא”א הרבון בשבת, דהמה מיירי בשבת לפי מנהגם שנ”כ בכל

יום, וקאי על שבת שבכל השנה. משא”כ במדינתנו שאין נו”כ אלא ביום טוב,

ולא משכחת אלא בשבת שחל ביום טוב, ויוכל להיות שבכה”ג אומרין גם בשבת, וכן

באמת המנהג פ”ק וולאזין לומר הרבון בשבת שחל ביום טוב… איברא הראיה

שהביא המ”א מאבינו מלכנו, שאין אומרים בשבת שחל בר”ה, ראיה חזקה היא,

אבל לפי טעם הלבוש שהביא המג”א (סי’ תרפ”ד) שהוא משום שנתיסד כנגד תפלת

שמונה עשרה ניחא הא דאין אומרים אבינו מלכנו, אבל תחינות מותר לאמרן, ובאמת הלבוש

הביא טעם הר”ן והריב”ש משום שאין מתריעין בתחינות בשבת, ודחה דשאני

ר”ה ויוהכ”פ, וממילא ה”ה כל יום טוב שהוא יומא דדינא, והראיה

שג”כ מרבים בתחנת גשם וטל, מותר לאמר גם הרבון לדעתי[44].

להוכיח על פי קבלה שאין לומר י”ג מידות בראש השנה ויום כיפור אפילו כשאינו חל

בשבת, וכל המנהג בטעות יסדו, ושזה אינו מהאר”י הקדוש לאחר שקיבל מאליהו

הנביא. עיי”ש באריכות הוכחותיו[45]. ומעניין

שר’ עובדיה יוסף קיבל דבריו וגם לדעתו אין לומר י”ג מדות ביום טוב[46].

סלימאן מני: “ובשעת הוצאת ספר תורה… בבית אל… אומרים י”ג מדות ואני

לא נהגתי לומר, ואפילו שהזכירה בשער הכוונות, דאיתא זכירה דיש מי שפקפק בזה מטעם

שאין אומרים י”ג מדות ביו”ט, וגם אתיא זכירה בחמדת ישראל שפקפק בזה,

ואמר כמדומה לי שכתב כן [האר”י ז”ל] בתחלת למודו. ולכן לא הנהגתי

לאומרו…”[47].

מפראג בספרו הנפלא ספר החיים:

הן שמותיו של הקדוש ברוך הוא וכמו ששמו קיים לעד ולנצח כך הזכרת מדותיו אינו חוזר

ריקם, מכל מקום אינו אומר שיהיו נזכרים, רק כסדר הזה יהיו עושין לפני לפי שהעשיה

הוא עיקר, שצריך האדם לדבוק באותן המדות ולעשותם, ובעשרה אפשר שיהיו נעשים, שזה

רחום וזה חנון, וזה ארך אפים וכן כולם, שעיקר המדות הללו הם עשר. ולפי שבדורותינו

זה יהיו נזכרים ולא נעשים, על כן אין אנו נענים בעונותינו הרבים[48].

עשר מדות שבם מרחם ומכפר לחוטאים וזאת היא תשובת שאלת הראני נא את כבודך, ולכן אמר

ויעבור ה’ על פניו, ללמדו היאך יסדר אלו הי”ג מדות הוא והנמשכים אחריו לביטול

הגזרות ולכפרת העונות, כאומרם ז”ל אלמלא מקרא כתיב אי אפשר לאומרו, כביכול

נתעטף בטליתו ואמר לו כ”ז שישראל עושים כסדר הזה אינן חוזרות ריקם, שנא’ הנה

אנכי כורת ברית. ופירושו ידוע, שהרי אנו רואים הרבה פעמים בעונותינו שאנו מעוטפים

בטלית ואין אנו נענין, אבל הרצון כל זמן שישראל עושים כסדר הזה שאני עושה, לרחם

לחנן דלים ולהאריך אפים ולעשות חסד אלו עם אלו, ולעבור על מדותיהן כאומרם כל

המעביר על מדותיו וכו’, אז הם מובטחים שאינן חוזרות ריקם. אבל אם הם אכזרים ועושי

רשעה, כל שכן שבהזכרת י”ג מדות הם נתפסין. וזהו וחנותי את אשר אחון, מי שראוי

לחול ולרחם עליו. ולכן הוצרך לומר ויעבור ה’, כאילו הוא מעצמו עבר לפניו ללמדו

כיצד יעשה וכיצד יקרא. כמו שהש”י קרא ואמר ה’ ה'”[49].

מההערה שכתבתי במאמרי ‘ציונים ומילואים לספר “מנהגי הקהילות”‘, ירושתנו,

ב (תשס”ח), עמ’ ריב-ריד. בעז”ה אכתוב על כך באריכות בספרי ‘עורו ישנים

משנתכם’.

בענין אמירת י”ג מידות ראה: שדי חמד מערכת יום כיפור סימן ב אות כא; ר’ ישראל

חיים פרידמאן, ליקוטי מהרי”ח, ג, ירושלים תשס”ג, עמ’ כז; ר’ שמואל מונק,

קונטרס תורת אמך (בסוף שו”ת פאת שדך או”ח, ח”ב), אות קד והערה

91; ר’ אברהם ראזען, שו”ת איתן אריה, סי’ קכ; י’ מונדשיין, אוצר מנהגי

חב”ד, ירושלים תשנ”ה, עמ’ קג; ר’ יהודה טשזנר, שערי הימים הנוראים,

תשע”א, עמ’ תשד-תשו.

כתבים נבחרים, א, ירושלים תשכ”ט, עמ’ 44-45; וראה מה שהעיר מ”ד צ’צ’יק,

‘עוד על סידור הגר”א’, המעין, מז, גל’ ד (תמוז תשס”ז), עמ’ 84 מס’ 9.

ספרות ההנהגות, ירושלים תש”ן, עמ’ 86 ואילך; יוסף אביב”י, קבלת

האר”י, ב, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 752-753.

ייחוס מנהג כיסוי השופר בשעת ברכות לב”ח ולשל”ה, ירושתנו ז

(תשע”ד), עמ’ שפא ואילך.

תשכ”ו.

תשכ”ו. על חיבורים אלו ראה מה שכתבתי בליקוטי אליעזר, ירושלים תש”ע, עמ’

יג ואילך.

מורחב של החיבור (נדפס לראשונה רק בשנת תרס”ה), דף לה ע”ב.

תש”ן, עמ’ 82 ואילך, 87 ואילך; יוסף אביב”י, קבלת האר”י, ב,

ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 593-595, ועמ’ 670-671.

עמ’ קפז.

חכמים, פראג תקע”ה, דף סה ע”א.

אלול, הארכתי בספרי ‘עורו ישנים משנתכם’.

תשע”ב, עמ’ עח.

עמ’ 98, ענף בקשה. עליו ראה: ג’ שלום, ‘ר’ אליהו הכהן האיתמרי והשבתאות’, ספר היובל לכבוד אלכסנדר מארכס, ניו יורק תש”י, עמ’ תנא-תע; וכן במבואו של ר”ש אשכנזי [לא על שמו] לשבט מוסר,

ירושלים תשכ”ג.

(ד”צ), עמ’ 223.

אליהו, ירושלים תשס”ו, עמ’ סט. וראה מש”כ ר’ בנימין שלמה המבורגר,

ירושתנו ב (תשס”ח), עמ’ תמא.

דור ודור, עמ’ פ אות טז, שכך נהגו בית הכנסת הגר”א בתל אביב.

תרס”ז, סי’ כט, דף לב ע”א. אי”ה אעסוק בחיבור זה בהזדמנות אחרת.

עמ’ 178.

סי’ תקפד ס”ק א.

המהדורה שי”ל ע”י אהבת שלום בתשע”ג.

מה.

תורה שם.

הקריאה, בערלין 1882, עמ’ 164.

במאמרי ”ציונים ומילואים למדור נטעי סופרים – על הגאון ר’ רפאל

נתן נטע רבינוביץ זצ”ל בעל דקדוקי סופרים’,

ישורון כד (תש”ע), עמ’ תכה-תכז.

תשס”ז, עמ’ קפה.

תש”ס, עמ’ 126; שו”ת גבורות אליהו, ירושלים תשע”ג, עמ’ רעב. וראה

שם עמ’ רצב והערה 1150.

רבינו, ב, בני ברק תשנ”ו, עמ’ רח.

הלוי, ברלין תרס”ז, עמ’ 28.

תשס”ז, עמ’ רצ.

ברלין, חולין תשס”ז, עמ’ 95.

עמ’ תקפו, אות פא. וכ”כ בשם ר’ שלמה זלמן אויערבאך, הליכות שלמה, ירושלים

תשס”ד, הלכות יום כיפור, פרק ד הערה 14.

במחזור כל בו, חלק ג, וילנא תרס”ה, עם הערות של ר’ אליהו דוד ראבינאוויץ

תאומים (האדר”ת) שנכתבו בשנת תר”ס. לאחרונה נדפסו מנהגים אלו בתוך ‘תפילת

דוד’, קרית ארבע תשס”ב, עמ’ קנז-קעז; ‘תפלת דוד’, ירושלים תשס”ד, עמ’

קלט-קנ. חלקם של המנהגים נדפסו על ידי ר’ יצחק ווייס, ‘אלף כתב’, ב, בני ברק

תשנ”ז, עמ’ ט-י. וראה: ר’ אליהו דוד ראבינאוויץ תאומים, סדר פרשיות, בראשית,

ירושלים תשס”ד, עמ’ שפד, אות 49.

עמ’ צא, אות סה.

לגדולי אוסטרהא, ברדיטשוב תרס”ז, עמ’ 42-46; ש’ הורדצקי, לקורות הרבנות,

וורשא תרע”א, עמ’ 183; ר’ ראובן

מרגליות, תולדות אדם, לבוב תרע”ב, עמ’ יז ועמ’ צ-צא.

אוסטרהא, ברדיטשוב תרס”ז, עמ’ 26-27.

ב, ירושלים תשס”ה, עמ’ נט.

עמ’ צא.

תשס”ט, עמ’ יט-כ; וזרח השמש, עמ’ לח אות כ, ועמ’ מז אות יד. וראה ר’ יוסף

הענקין, שו”ת גבורות אליהו, ירושלים תשע”ג, עמ’ רצב והערה 1150.

וראה עוד מה שכתב בענין זה ב’נספח ללוח מנהגי בית הכנסת לבני אשכנז’, ירושתנו ב

(תשס”ח), עמ’ תמא.

שבת, עמ’ קכד. וראה ר’ יעקב פישר, קונטרס בקשות בשבת, ירושלים תשס”ה, עמ’ לה;

ר’ יהושע כהן, אזור אליהו, ירושלים תשס”ו, עמ’ תרז-תריא.

משיב דבר חלק א סימן מז.

סי’ יא. וראה דבריו בהקדמה ל’שער התפלה’, ירושלים תשס”ח, עמ’ 24. וראה ר’

דניאל רימר, תפילת חיים, ביתר תשס”ד, עמ’ רמו-רמח.

קט.

אליהו סלימאן מני, מנהגי ק”ק בית יעקב בחברון, ירושלים תשנ”א, עמ’ לב, אות עא. וראה שם, עמ’ מא אות פג לענין

יו”כ.

ספר סליחה ומחילה, פ”ח, עמ’ קפג.

א, עמ’ תפח [דודי ר’ שלום יוסף שפיץ הפנני למקור זה]. וראה מה שכתב ר’ דוד צבי רוטשטיין,

מידת סדום, ירושלים תשנ”א, עמ’ 138 ואילך.

Le-Tacen Olam (לתכן עולם): Establishing the Correct Text in Aleinu

The sentence from the liturgy referred to (…זה היום) is from the introductory section to the ten verses of zikhronot. A reasonable inference from these Talmudic passages is that Rav composed (at least) the introductory sections to zikhronot, malkhuyyot and shofarot. Aleinu

is part of the introductory section to malkhuyyot. Since the sentence from the introduction to zikhronot quoted corresponds to the present

introduction to zikhronot, it is reasonable to assume that their introduction to malkhuyyot corresponded to the present introduction to malkhuyyot, i.e., that it included Aleinu. Admittedly, Rav could have made use of older material in the introductory sections he composed. The fact that Aleinu has been found (in a modified version) in heikhalot literature is some evidence for Aleinu’s existence in this early period, even though the prayer is not specifically mentioned in any Mishnaic or Talmudic source. (Regarding the dating of heikhalot literature, see below.) On the version of Aleinu in heikhalot literature, see Michael D. Swartz, “ ‘Alay Le-Shabbeaḥ: A Liturgical Prayer in Ma‘aseh Merkabah,” Jewish Quarterly Review 77 (1986-1987), pp. 179-190. See also the article by Bar-Ilan cited above. For parallels in later sources to the two passages from the Jerusalem Talmud, see Swartz, p. 186, n. 20. See also Rosh ha-Shanah 27a.

pp. 379-380. Statements that Aleinu was composed by Joshua are found in various Ashkenazic Rishonim. This idea seems to have originated with R. Judah he-Hasid (d. 1217). For the references, see Wolfson, pp. 380-381.

very clear that Ecclesiastes is a late Biblical book See EJ 2:349.)

edition, the Mechon Mamre edition (www.mechon-mamre.org), and the editions published by R. Yitzḥak Sheilat and by R. Yosef Kafaḥ. All

print לתכן. (The Frankel edition does note that a small number of manuscripts read לתקן.)

is known as Cambridge Add. 3160, no. 10. When Mann published the fragment, he erroneously printed לתקן.

“examine,” “measure,” or “place in order.” (At Psalms 75:4, עמודיה תכנתי, the root is commonly translated as “establish,” but even here it probably means something like “properly apportion” or “place in order.” See, e.g., the commentary of S. R. Hirsch.) תכן with the meaning “establish” is not found in the Mishnah or Tosefta. But תכן may mean “establish” in the Dead Sea text 4Q511: שנה למועדי תכן (DJD VII, p. 221), and perhaps in other Dead Sea texts as well.

presumption should be one of unitary authorship. Close analysis of the verses cited shows that both sections quote or paraphrase from the same chapter of Isaiah (45:20: u-mitpallelim el el lo yoshia and 45:23: ki li tikhra kol berekh tishava kol lashon; there are quotes and paraphrases of other verses from chapter 45, and from 44:24 and 46:9 as well.) This strongly suggests that both sections were composed at the same time. (I have not seen anyone else make this point.) Terms characteristic of heikhalot literature are found in both sections as well.

A New Work about the Ramban’s Additions to his Commentary on the Torah

A New Work about the Ramban’s Additions to his Commentary on the Torah

By Eliezer Brodt

.תוספות רמב“ן לפירושו לתורה, שנכתבו בארץ ישראל, יוסף עופר, יהונתן יעקבס, מכללה הרצוג, והאיגוד העולמי למדעי היהדות, 718 עמודים

In this post I would like to explain what this work is about.

One of the most important Rishonim was Rabbi Moshe Ben Nachman, famously known as Ramban. Ramban was famous for numerous reasons and has been the subject of numerous works and articles.[1] This year alone two important works were written about him, one from Dr. Shalem Yahalom called Bein Gerona LeNarvonne, printed by the Ben Tzvi Institute and another one from Rabbi Yoel Florsheim called Pirushe HaRamban LeYerushalmi: Mavo, printed by Mossad Harav Kook.

One of Ramban’s most lasting achievements was his commentary on the Torah. This work is considered one of the most essential works ever written on the Chumash. Scholars debate when exactly he write this work, but it appears that he completed the commentary before he left Spain for Eretz Yisroel in 1269. For centuries this commentary has been one of the most studied works on Chumash. However, what is less known is that some time after he arrived in Eretz Yisroel he continued to update his work and sent numerous corrections and additions back his students in Spain.

Correcting and updating works was not an unusual phenomenon in the time of the Rishonim in the Middle ages, as Professor Yakov Spiegel has documented in his special book Amudim Betoldos Hasefer Haivri, Kesivah and Ha’atakah, and many authors at the time practiced this.

We find that R’ Yitzchak Di-min Acco already writes:

.וראיתי לבאר בו המדרש שכתב הרמב”ן ז”ל באחרית ימיו בארץ הצבי, בעיר עכו ת”ו בתשלום פירושו התורה אשר חברו [מאירת עינים, עמ’ שכז]\

Many knowledgeable people know of some pieces where Ramban clearly writes that when he arrived in Eretz Yisroel he realized he had erred in his commentary. One of the most famous of such pieces is what he writes in regard to the location of Kever Rochel[2]:

זה כתבתי תחילה, ועכשיו שזכיתי ובאתי אני לירושלם, שבח לאל הטוב והמטיב, ראיתי בעיני שאין מן קבורת רחל לבית לחם אפילו מיל. והנה הוכחש הפירוש הזה, וגם דברי מנחם. אבל הוא שם מדת הארץ כדברי רש”י, ואין בו תאר רק הסכמה כרוב השמות, והכ”ף לשמוש שלא נמדד בכוון… וכן ראיתי שאין קבורה ברמה ולא קרוב לה, אבל הרמה אשר לבנימן רחוק ממנה כארבע פרסאות, והרמה אשר בהר אפרים (ש”א א א) רחוק ממנה יותר משני ימים. על כן אני אומר שהכתוב שאומר קול ברמה נשמע .(ירמיה לא יד), מליצה כדרך משל… [רמב”ן בראשית לה:טז]\

A different correction to Ramban’s commentary was a letter found at the end of some of the manuscripts of his work, where he writes about the weight of the Biblical Shekel, retracting what he writes in his work on Chumash. Early mention of this letter can be found in the sefer Ha-ikryim

וכן העיד הרמב”ן ז”ל כי כשעלה לארץ ישראל מצא שם בעכו מטבע קדום של כסף שהיה רשום בו צנצנת המן ומטה אהרן שהיה כתוב סביבו כתב שלא ידע לקרותו, עד שהראו לכותיים לפי שהוא כתב עברי הקדום שנשאר אצל הכותיים, וקראו הכתב ההוא והיה כתוב בו שקל השקלים. ואלו הם הדברים שהגיה בסוף פירושו וששלח מארץ ישראל…[ספר העיקרים מאמר ג פרק טז]

This important letter was printed based on a few manuscripts by Rabbi Menachem Eisenstadt in the Talpiot journal in 1950. Rabbi Eisenstadt included an excellent introduction elaborating on the background about this letter and its importance. In 1955 Rabbi Yonah Martzbach was made aware of this article by Rabbi Kalman Kahana while he was preparing the entry ‘Dinar’ for the Encyclopedia Talmudit. He wrote a letter to Rabbi Eisenstadt with some minor comments and requested a copy of this article. A short while later Rabbi Eisenstadt responded thanking him for his comments.[3]

Ramban’s above mentioned letter has been dealt with at length by Rabbi Yakov Weiss in his Midos Umishklos Shel hatorah (pp. 96-97, 113-116) and by Rabbi Shmuel Reich in his Mesorat Hashekel (pp. 83-98).[4]

But no one realized just how many such corrections there were.

In 1852, and again in 1864, Moritz Steinschneider discovered that there were several manuscripts of Ramban’s commentary that had lists of numerous additions at the end of the work. However, he was not sure who authored them.

In 1950, Rabbi Eisenstadt [in the aforementioned article] mentions that in back of a manuscript of Ramban’s commentary there are additions to the pirush, which were written in Eretz Yisroel. In 1958, Rabbi Eisenstadt began printing his edition of Ramban’s commentary with the pirish called Zichron Yitzchak. In his notes throughout the work, he points out the various additions he found highlighted in the manuscript. Unfortunately he never completed his work and only the volume on Bereishis was printed.

In 1969, Rabbi Kalman Kahana printed an article which had a list of all the corrections and updates found in a few manuscripts of Ramban’s commentary. Rabbi Kahana’s list numbered at 134 corrections and additions to Ramban’s commentary. He also included explanations to some of these additions to show their significance in understanding various pieces of Ramban’s commentary. Rabbi Kahana reprinted this article in 1972 in his collection called Cheikar Veiun (volume three). After this article, the subject was barely discussed.

In the edition Ramban’s pirush, printed in 1985 by Rabbi Pinchas Lieberman, with his commentary Tuv Yerushlayim, I did not find that he makes any mention of Rabbi Kahana’s article.

In 2001, Rabbi Dvir began printing an edition of Ramban’s commentary with a super-commentary called Beis Hayayin. In the back of volume one, he reprints Rabbi Kahana’s article, however he barely deals with the topic throughout the sefer.

In 2004, Artscroll began printing a translation of Ramban’s pirush along with a super-commentary. In their introduction, the editors write that besides making use of various manuscripts for establishing their text of Ramban’s pirush, they also used Rabbi Kahana’s list and that they identify the corrected pieces of Ramban’s pirush throughout the work.

In 2006, Mechon Yerushalyim started printed an edition of Ramban’s commentary. In the beginning of their edition, they mention that Ramban added pieces to the commentary after he arrived in Eretz Yisroel and that they will identify those pieces. However, they do not mention the source for those identifications.

In 2009, Mechon Oz Vehadar began printing an edition of the Pirush with a super-commentary. In their Introduction (p. 26), the editors write that they also made use of Rabbi Kahana’s list:

אחרי שעלה רבינו לארץ ישראל הוסיף והגיה בפירושו בכמה מקומות, אשר נמצאו רק במקצת כתבי היד, הוספות אלו נדפסו ללא כל סימן היכר, ובמהדורותינו זיהינו אותם וציינו אליהם, כי לפעמים ההוספה של רבינו אינה נקראת בתוך שטף דבריו, והלומד מתקשה בשינוי הלשון [וגם כי לפעמים מה שהוסיף רבינו אינו אלא כאחד מן הפירושים שהביא מתחילה, ונראה כביכול שהכריע בהוספתו שלא כשאר פירושים, ועל כן חשוב לציין כי זו הוספה שנוספה לאחר מכן…] הוספות אלו ציינו על פי עבודתו ופרי יגיעת הר”ר קלמן כהנא ז”ל, שחקר ובירר ענין זה והדפיסו בחקר ועיון (ח”ג)

All of the above work was done based solely upon the 134 corrections listed by Rabbi Kahana.

In 1997, Hillel Novetsky submitted a paper to Professor David Berger titled “Nahmanides Amendments to his Commentary on the Torah”. In this paper Novetsky deals with what we can learn from these 134 additions to the Pirush and why Ramban added them in. Amongst the reasons for Ramban’s changes, Novetsky points to a firsthand knowledge of the geography of Eretz Yisroel, newly obtained literature (such as Pirush Rabbenu Chananel on Chumash) and general additions based on new thoughts and the like. Recently, Novetsky has returned to this topic, as can be seen here. He also put up online the numerous additions he found while going through the various manuscripts of the Pirush.[5] He discovered that there are actually much more than 134 updates and corrections. However he recommends checking back as not all of his information has been uploaded.

In 2005, Dr. Mordechai Sabato printed a lengthy article[6] dealing with Ramban’s additions to his commentary to Bereishis, showing that a study of the manuscripts shows there are more additions than the number published by Rabbi Kahana. He discovered what he believes are other pieces that were added into the work at a later time which were not included in the lists at the end of some of the manuscripts. In this study he also shows the importance of some of these additions.

Which brings us to the focus of our review Tosfot HaRamban LiPirusho LeTotrah. In this new work , Dr’s Yosef Ofer and Yonasan Jacobs deal with all of issues mentioned the above, and then some. In recent years these scholars have been working on Ramban’s additions, building off of Dr. Sabato’s work and lectures. In various articles they have added much to this subject. For example, see here and here. In this new work of theirs they collected over 300 additions and corrections by Ramban, based on over 50 manuscripts of Ramban’s commentary. Along with Dr. Sabato’s methods, they identified additional ways to note the additions within the Pirush. They were able to categorize the various manuscripts into two divisions; earlier versions and later versions. All this is elaborated carefully in their lengthy introduction to this work. They are able to show how they identified numerous new additions and corrections not found in the previous lists. Almost all of these additions and corrections can be found in the standard editions of the Pirush, however they are not identified as such. In many cases, these unmarked additions cause Ramban’s meaning to become unclear. In the current work, each piece of Ramban’s commentary where they note an addition or correction has been reprinted based on the manuscripts along with a standard academic apparatus of variant readings of the particular text. They then highlight the exact addition or correction made by Ramban to the piece. After laying this textual foundation, they then provide a well written, clear, and concise discussion about the particular piece, explaining why they believe Ramban amended the text in question or what he was adding to the original commentary. Numerous pieces of Ramban’s commentary, which were not properly understood until now, can now be more clearly grasped.

Based on these additions, Dr’s Ofer and Jacobs provide a very good summary in the introduction to their work of various aspects of Ramban’s life and his commentary, along with a section beneficial to understanding how Ramban wrote his work, such as the role played by the various newly obtained literature he saw in Eretz Yisroel and had become a part of his source material.

Also worth pointing out is their edition of the aforementioned letter where he writes about the weight of the Biblical Shekel, retracting what he writes in his work on Chumash based on all the manuscripts (pp. 337-342).

This work is very important and highly recommended for any serious student of Ramban’s commentary, who wishes to understand numerous hitherto fore unclear passages in the Pirush.

Interestingly enough, although the Chavel edition of the Ramban, printed by Mossad Rav Kook, is based on some manuscripts and is for itself an important contribution to the understanding of Ramban’s commentary,[7] while the editor does note that there are some new pieces in the manuscripts, he did not fully grasp their significance nor did he gauge the full sum of these changes. Although he first printed his work in 1960, he was apparently not aware of Rabbi Menachem Eisenstadt in the Talpiot journal in 1950, as is evident from his comments to the letter of the Ramban printed in the back of his edition of the Ramban Al Hatorah (pp. 507-508), despite the fact that though he does cite the entry ‘Dinar’ from the Encyclopedia Talmudit which itself quotes Rabbi Eisenstadt’s article a few times. What is even stranger is over the years Rabbi Chavel updated his edition of Ramban Al Hatorah numerous times, yet apparently he never heard of Rabbi Kalman Kahana’s article listing 134 corrections and additions.

Professor Ta-Shema notes about Ramban:

ותשומת הלב העיקירת במחקר הוסטה על עבר מעמדו של הרמב”ן בתחום חכמי הקבלה הספרדית המתחדשת, ובמעט גם לעבדותו בתחום פרשנות המקרא. המעט שכתב הרמב”ן בחכמת הקבלה, שאינו מצרטף ליותר מכריסר עמודים בסך הכול, לא חדל מלהעסיק את המחקר המדעי שנים רבות, ואילו עבודתו המקיפה בפרשנות התלמוד, המהווה את עיקר פרסומו והשפעתו בשעתו ולדורות לא זכה לעיון ביקורתי… [הספרות הפרשנית לתלמוד, ב, עמ’ 32]

Although some serious advances have been seen recently in the field of Ramban’s Talmudic Novella, especially by Dr’s Shalem Yahalom and Yoel Florsheim in their works mentioned in the beginning of this article, however much research still remains to be done.

Daniel Abrams, in an article first printed in the Jewish Studies Quarterly and then updated in his recent book Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory (pp.215-218), outlines a project to print a proper edition of Ramban’s commentary on Torah, based upon all extant manuscripts and including all the known super-commentaries written on the work, both printed and those still in manuscript.[8] This would help reach a proper understanding of Ramban’s Pirush. Abrams’s main concern is with reaching a proper understanding of Ramban’s Torat HaKabalah, but as the bulk of the Pirush is not of a kabbalistic nature, such an edition would benefit everyone greatly. Unfortunately due to lack of funds nothing has yet happened with Abrams’s proposal.

Dr’s Ofer and Jacobs’s new work, based on the numerous extant manuscripts of the Pirush has definitely helped us in getting closer to a proper understanding of Ramban’s work on Torah.[9] We can only hope with time Abrams’s proposal will bear fruit.

For information on purchasing this work, contact me at: Eliezerbrodt@gmail.com Copies are available at Biegeleisen in New York. E-mail if you are interested in a table of contents or a PDF of Rabbi Kalman Kahana’s article.

[1] For a useful write up about the importance of the Ramban, see Yisroel M. Ta-Shema , Ha Safrut Haparshnit LiTalmud, 2, pp. 29-55. I am in middle of attempting to write a complete bibliography of all his writings and studies related to everything he wrote.

[3] On the location of Kever Rochel see Kaftor Vaferach [1:246-247; 2:69]; Tevuot HaAretz, pp. 131-135. See also Tosfot HaRamban LiPirusho LeTotrah, pp. 229-233, 287-292

[3] This article of Rabbi Eisenstadt was reprinted recently in his a collection of his writings called Minchat Tzvi, New York 2003, pp. 125-138. The letter of Rabbi Martzbach is also printed there (pp. 139-140) along with Rabbi Eisenstadt response. The letter of Rabbi Martzbach is also printed in Alei Yonah with some additions but without Rabbi Eisenstadt response (pp. 155-157). The Alei Yonah edition does not say to whom the letter was written to. They also edited out his request for a copy of the article.

[4] See also here.

[5] Thanks to Professor Haym Soloveitchik for pointing this out to me.

[6] Megadim 42 (2005), pp. 61-124.

[7] That is besides for the various criticism of the work, beyond the scope of this article. [See this earlier post].

[8] The recent edition of the Ramban printed by Mechon Yerushalayim is a far cry from what needs to be done for this purpose.

[9] See here for another article of Dr. Ofer which demonstrates the benefit of the manuscripts of the Ramban to reach an understanding of the Ramban.

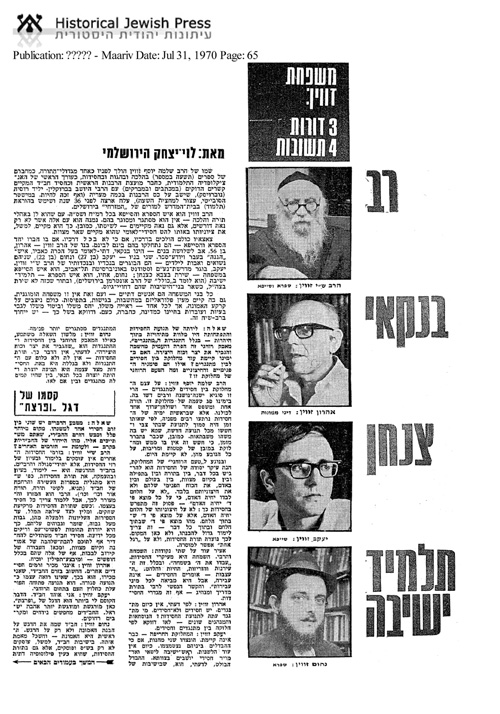

R. Shlomo Yosef Zevin and the Army, and Joe DiMaggio

Regarding the essay and its attribution to R. Zevin, R. Chaim Rapoport has commented to me that since the essay has two references to Shulhan Arukh ha-Rav, this too would seem to point to R. Zevin’s authorship. There is little doubt that in this sort of essay only a Habad author would refer to Shulhan Arukh ha-Rav.

Surprisingly, however, the person who inserted this information apparently did not know what to make of the pseudonym ב”מ-ו עזפמט. It doesn’t take much imagination to see that in atbash this equals ש”י-ף זעוין. See Aharon Sorasky, Melekh be-Yafyo ((Jerusalem, 2004), pp. 188-189. See also ibid., p. 241 n. 12, for another time when R. Abramsky signed an article אחד הרבנים.

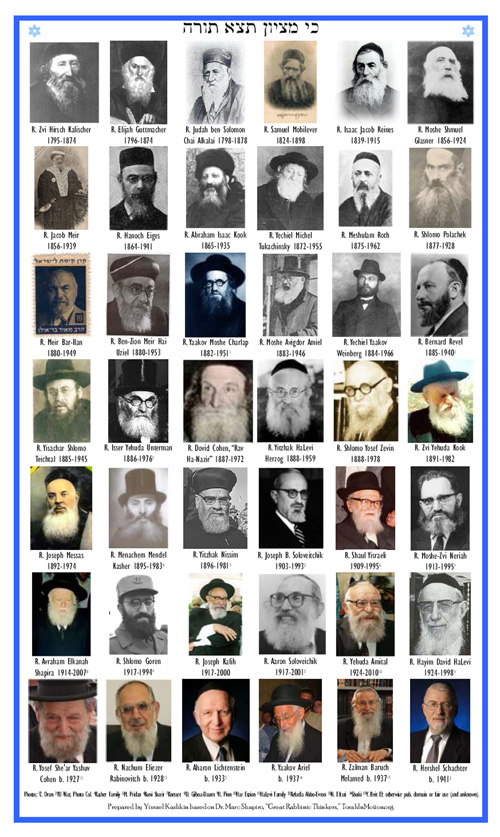

Finally, here is something very nice put together by Yisrael Kashkin. Most of the great rabbis included were what we can call card-carrying Religious Zionists, and the remaining few were positively inclined to the movement. Not surprisingly, R. Zevin’s picture is found here. Kashkin informs me that anyone interested can order framed 8.5 x 14″ and laminated 8.5 x 14″ copies. The former are meant for a wall and the latter for a Succah. He can prepare and ship the frames for $25 and the laminated for $10. You can contact him at yisrael@email.com. I recommend that every Modern Orthodox school order an enlarged copy in order to hang it in the hallway.

3. In case anyone is interested, for some reason Amazon is now selling my book Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy for the low price of $16.63. This is a 33% discount..

Since I mention Merkaz, let me also note two little known facts that would be unimaginable today. For a long time there was a special shiur given by R. Zvi Yehudah Kook in his home for students and graduates of the Chevron yeshiva. Also, for one winter “zeman” R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach gave a shiur for students of the highest class at Kol Torah together with students of Merkaz (and it was the Merkaz students who took the initiative in organizing the shiur). See R. Yitzhak Sheilat, “Mi-Seridei Dor ha-Nefilim” in Itamar Warhaftig, ed., Afikei Yehudah (Jerusalem, 2005), p. 18.

Two more points about haredim and the army: (1) There have been some incidents of violence directed against haredi soldiers from extremist haredim. This is not unexpected and one can expect more of this in the future, and it also has historical precdent. See e.g., Degel Mahaneh Ephraim (Elitzur Memorial Volume; Bnei Brak [2012]), p. 304, regarding how a group of Ponovezh students beat up one of their co-students who joined the Irgun. This led to the beaten student entirely abandoning religious life. (2) I might have missed it, but in all the haredi attacks on efforts to draft haredim, I haven’t seen anyone cite Nedarim 32a which states that Abraham was punished and his descendants doomed to Egyptian slavery “because he pressed scholars into his service, as it is written, He armed his dedicated servants born in his own house (Gen. 14:14).”

Regarding the haredi stress on Torah study above all else (and certainly army service) a reader called my attention to R. Hayyim Kanievsky, Derekh Sihah, vol. 2, p. 300, who explains why at a circumcision we speak of raising a boy to “Torah, huppah, and ma’asim tovim.” Shouldn’t “ma’asim tovim” come before “huppah“? R. Kanievsky explains that before marriage the young man should only be focused on Torah, nothingelse. Ma’asim tovim, i.e., hesed, can come after marriage, but should not interfere with a young man’s intensive Torah study..

I began to think about Palestine. My imagination played strongly and emphatically upon my mind, so that at last I decided to try. I went to Rabbi Meltzer and told him that I would like to go to Palestine with him. At first he hardly realized what I was driving at, but when I unfolded my plan that I would like to go to Rabbi Kook’s Yeshiva, he immediately agreed, possibly because he himself was zionistically inclined and he liked the plan. I immediately wrote a letter to Rabi Kook to which Rabbi Meltzer added a few words of praise about me. . . .

When it became known that I intended to go to Palestine, Rabbi Kottler [!] became furious. He called me and strongly scolded me for my venture. When he saw that I was adamant, he reminded me of my first act of disobedience and rebellion. He simply told me that I had no place in his Yeshiva anymore. This was a hard blow to me. Where could I go? How could I find food to eat? But the Almighty had not forsaken me. When Rabbi Meltzer heard of this situation, he offered me to come to stay in his house until I could go to Eretz Israel. . . . Now that I was provided with board and lodgings, I could manage without the allowance which Rabbi Kottler had withheld from me, and I could continue planning on how to get to Israel.

[4] This is incorrect. Contrary to what it says in the Hebrew Wikipedia. Panim el Panim was still published in 1973 (it stopped sometime that year) See the JNUL catalog (MS)