A New Work about the Ramban’s Additions to his Commentary on the Torah

A New Work about the Ramban’s Additions to his Commentary on the Torah

By Eliezer Brodt

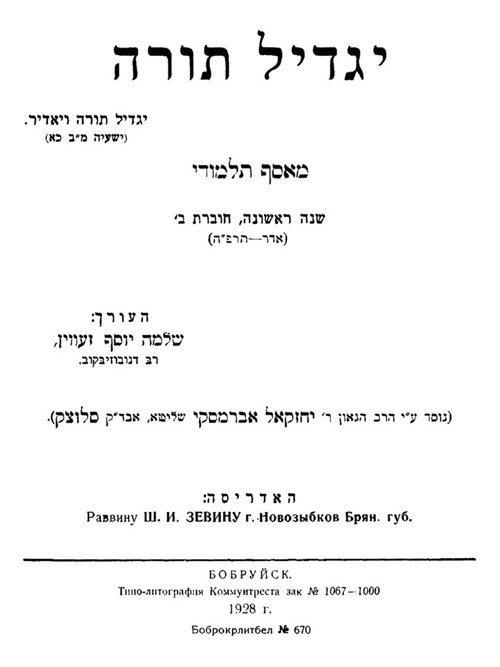

.תוספות רמב“ן לפירושו לתורה, שנכתבו בארץ ישראל, יוסף עופר, יהונתן יעקבס, מכללה הרצוג, והאיגוד העולמי למדעי היהדות, 718 עמודים

In this post I would like to explain what this work is about.

One of the most important Rishonim was Rabbi Moshe Ben Nachman, famously known as Ramban. Ramban was famous for numerous reasons and has been the subject of numerous works and articles.[1] This year alone two important works were written about him, one from Dr. Shalem Yahalom called Bein Gerona LeNarvonne, printed by the Ben Tzvi Institute and another one from Rabbi Yoel Florsheim called Pirushe HaRamban LeYerushalmi: Mavo, printed by Mossad Harav Kook.

One of Ramban’s most lasting achievements was his commentary on the Torah. This work is considered one of the most essential works ever written on the Chumash. Scholars debate when exactly he write this work, but it appears that he completed the commentary before he left Spain for Eretz Yisroel in 1269. For centuries this commentary has been one of the most studied works on Chumash. However, what is less known is that some time after he arrived in Eretz Yisroel he continued to update his work and sent numerous corrections and additions back his students in Spain.

Correcting and updating works was not an unusual phenomenon in the time of the Rishonim in the Middle ages, as Professor Yakov Spiegel has documented in his special book Amudim Betoldos Hasefer Haivri, Kesivah and Ha’atakah, and many authors at the time practiced this.

We find that R’ Yitzchak Di-min Acco already writes:

.וראיתי לבאר בו המדרש שכתב הרמב”ן ז”ל באחרית ימיו בארץ הצבי, בעיר עכו ת”ו בתשלום פירושו התורה אשר חברו [מאירת עינים, עמ’ שכז]\

Many knowledgeable people know of some pieces where Ramban clearly writes that when he arrived in Eretz Yisroel he realized he had erred in his commentary. One of the most famous of such pieces is what he writes in regard to the location of Kever Rochel[2]:

זה כתבתי תחילה, ועכשיו שזכיתי ובאתי אני לירושלם, שבח לאל הטוב והמטיב, ראיתי בעיני שאין מן קבורת רחל לבית לחם אפילו מיל. והנה הוכחש הפירוש הזה, וגם דברי מנחם. אבל הוא שם מדת הארץ כדברי רש”י, ואין בו תאר רק הסכמה כרוב השמות, והכ”ף לשמוש שלא נמדד בכוון… וכן ראיתי שאין קבורה ברמה ולא קרוב לה, אבל הרמה אשר לבנימן רחוק ממנה כארבע פרסאות, והרמה אשר בהר אפרים (ש”א א א) רחוק ממנה יותר משני ימים. על כן אני אומר שהכתוב שאומר קול ברמה נשמע .(ירמיה לא יד), מליצה כדרך משל… [רמב”ן בראשית לה:טז]\

A different correction to Ramban’s commentary was a letter found at the end of some of the manuscripts of his work, where he writes about the weight of the Biblical Shekel, retracting what he writes in his work on Chumash. Early mention of this letter can be found in the sefer Ha-ikryim

וכן העיד הרמב”ן ז”ל כי כשעלה לארץ ישראל מצא שם בעכו מטבע קדום של כסף שהיה רשום בו צנצנת המן ומטה אהרן שהיה כתוב סביבו כתב שלא ידע לקרותו, עד שהראו לכותיים לפי שהוא כתב עברי הקדום שנשאר אצל הכותיים, וקראו הכתב ההוא והיה כתוב בו שקל השקלים. ואלו הם הדברים שהגיה בסוף פירושו וששלח מארץ ישראל…[ספר העיקרים מאמר ג פרק טז]

This important letter was printed based on a few manuscripts by Rabbi Menachem Eisenstadt in the Talpiot journal in 1950. Rabbi Eisenstadt included an excellent introduction elaborating on the background about this letter and its importance. In 1955 Rabbi Yonah Martzbach was made aware of this article by Rabbi Kalman Kahana while he was preparing the entry ‘Dinar’ for the Encyclopedia Talmudit. He wrote a letter to Rabbi Eisenstadt with some minor comments and requested a copy of this article. A short while later Rabbi Eisenstadt responded thanking him for his comments.[3]

Ramban’s above mentioned letter has been dealt with at length by Rabbi Yakov Weiss in his Midos Umishklos Shel hatorah (pp. 96-97, 113-116) and by Rabbi Shmuel Reich in his Mesorat Hashekel (pp. 83-98).[4]

But no one realized just how many such corrections there were.

In 1852, and again in 1864, Moritz Steinschneider discovered that there were several manuscripts of Ramban’s commentary that had lists of numerous additions at the end of the work. However, he was not sure who authored them.

In 1950, Rabbi Eisenstadt [in the aforementioned article] mentions that in back of a manuscript of Ramban’s commentary there are additions to the pirush, which were written in Eretz Yisroel. In 1958, Rabbi Eisenstadt began printing his edition of Ramban’s commentary with the pirish called Zichron Yitzchak. In his notes throughout the work, he points out the various additions he found highlighted in the manuscript. Unfortunately he never completed his work and only the volume on Bereishis was printed.

In 1969, Rabbi Kalman Kahana printed an article which had a list of all the corrections and updates found in a few manuscripts of Ramban’s commentary. Rabbi Kahana’s list numbered at 134 corrections and additions to Ramban’s commentary. He also included explanations to some of these additions to show their significance in understanding various pieces of Ramban’s commentary. Rabbi Kahana reprinted this article in 1972 in his collection called Cheikar Veiun (volume three). After this article, the subject was barely discussed.

In the edition Ramban’s pirush, printed in 1985 by Rabbi Pinchas Lieberman, with his commentary Tuv Yerushlayim, I did not find that he makes any mention of Rabbi Kahana’s article.

In 2001, Rabbi Dvir began printing an edition of Ramban’s commentary with a super-commentary called Beis Hayayin. In the back of volume one, he reprints Rabbi Kahana’s article, however he barely deals with the topic throughout the sefer.

In 2004, Artscroll began printing a translation of Ramban’s pirush along with a super-commentary. In their introduction, the editors write that besides making use of various manuscripts for establishing their text of Ramban’s pirush, they also used Rabbi Kahana’s list and that they identify the corrected pieces of Ramban’s pirush throughout the work.

In 2006, Mechon Yerushalyim started printed an edition of Ramban’s commentary. In the beginning of their edition, they mention that Ramban added pieces to the commentary after he arrived in Eretz Yisroel and that they will identify those pieces. However, they do not mention the source for those identifications.

In 2009, Mechon Oz Vehadar began printing an edition of the Pirush with a super-commentary. In their Introduction (p. 26), the editors write that they also made use of Rabbi Kahana’s list:

אחרי שעלה רבינו לארץ ישראל הוסיף והגיה בפירושו בכמה מקומות, אשר נמצאו רק במקצת כתבי היד, הוספות אלו נדפסו ללא כל סימן היכר, ובמהדורותינו זיהינו אותם וציינו אליהם, כי לפעמים ההוספה של רבינו אינה נקראת בתוך שטף דבריו, והלומד מתקשה בשינוי הלשון [וגם כי לפעמים מה שהוסיף רבינו אינו אלא כאחד מן הפירושים שהביא מתחילה, ונראה כביכול שהכריע בהוספתו שלא כשאר פירושים, ועל כן חשוב לציין כי זו הוספה שנוספה לאחר מכן…] הוספות אלו ציינו על פי עבודתו ופרי יגיעת הר”ר קלמן כהנא ז”ל, שחקר ובירר ענין זה והדפיסו בחקר ועיון (ח”ג)

All of the above work was done based solely upon the 134 corrections listed by Rabbi Kahana.

In 1997, Hillel Novetsky submitted a paper to Professor David Berger titled “Nahmanides Amendments to his Commentary on the Torah”. In this paper Novetsky deals with what we can learn from these 134 additions to the Pirush and why Ramban added them in. Amongst the reasons for Ramban’s changes, Novetsky points to a firsthand knowledge of the geography of Eretz Yisroel, newly obtained literature (such as Pirush Rabbenu Chananel on Chumash) and general additions based on new thoughts and the like. Recently, Novetsky has returned to this topic, as can be seen here. He also put up online the numerous additions he found while going through the various manuscripts of the Pirush.[5] He discovered that there are actually much more than 134 updates and corrections. However he recommends checking back as not all of his information has been uploaded.

In 2005, Dr. Mordechai Sabato printed a lengthy article[6] dealing with Ramban’s additions to his commentary to Bereishis, showing that a study of the manuscripts shows there are more additions than the number published by Rabbi Kahana. He discovered what he believes are other pieces that were added into the work at a later time which were not included in the lists at the end of some of the manuscripts. In this study he also shows the importance of some of these additions.

Which brings us to the focus of our review Tosfot HaRamban LiPirusho LeTotrah. In this new work , Dr’s Yosef Ofer and Yonasan Jacobs deal with all of issues mentioned the above, and then some. In recent years these scholars have been working on Ramban’s additions, building off of Dr. Sabato’s work and lectures. In various articles they have added much to this subject. For example, see here and here. In this new work of theirs they collected over 300 additions and corrections by Ramban, based on over 50 manuscripts of Ramban’s commentary. Along with Dr. Sabato’s methods, they identified additional ways to note the additions within the Pirush. They were able to categorize the various manuscripts into two divisions; earlier versions and later versions. All this is elaborated carefully in their lengthy introduction to this work. They are able to show how they identified numerous new additions and corrections not found in the previous lists. Almost all of these additions and corrections can be found in the standard editions of the Pirush, however they are not identified as such. In many cases, these unmarked additions cause Ramban’s meaning to become unclear. In the current work, each piece of Ramban’s commentary where they note an addition or correction has been reprinted based on the manuscripts along with a standard academic apparatus of variant readings of the particular text. They then highlight the exact addition or correction made by Ramban to the piece. After laying this textual foundation, they then provide a well written, clear, and concise discussion about the particular piece, explaining why they believe Ramban amended the text in question or what he was adding to the original commentary. Numerous pieces of Ramban’s commentary, which were not properly understood until now, can now be more clearly grasped.

Based on these additions, Dr’s Ofer and Jacobs provide a very good summary in the introduction to their work of various aspects of Ramban’s life and his commentary, along with a section beneficial to understanding how Ramban wrote his work, such as the role played by the various newly obtained literature he saw in Eretz Yisroel and had become a part of his source material.

Also worth pointing out is their edition of the aforementioned letter where he writes about the weight of the Biblical Shekel, retracting what he writes in his work on Chumash based on all the manuscripts (pp. 337-342).

This work is very important and highly recommended for any serious student of Ramban’s commentary, who wishes to understand numerous hitherto fore unclear passages in the Pirush.

Interestingly enough, although the Chavel edition of the Ramban, printed by Mossad Rav Kook, is based on some manuscripts and is for itself an important contribution to the understanding of Ramban’s commentary,[7] while the editor does note that there are some new pieces in the manuscripts, he did not fully grasp their significance nor did he gauge the full sum of these changes. Although he first printed his work in 1960, he was apparently not aware of Rabbi Menachem Eisenstadt in the Talpiot journal in 1950, as is evident from his comments to the letter of the Ramban printed in the back of his edition of the Ramban Al Hatorah (pp. 507-508), despite the fact that though he does cite the entry ‘Dinar’ from the Encyclopedia Talmudit which itself quotes Rabbi Eisenstadt’s article a few times. What is even stranger is over the years Rabbi Chavel updated his edition of Ramban Al Hatorah numerous times, yet apparently he never heard of Rabbi Kalman Kahana’s article listing 134 corrections and additions.

Professor Ta-Shema notes about Ramban:

ותשומת הלב העיקירת במחקר הוסטה על עבר מעמדו של הרמב”ן בתחום חכמי הקבלה הספרדית המתחדשת, ובמעט גם לעבדותו בתחום פרשנות המקרא. המעט שכתב הרמב”ן בחכמת הקבלה, שאינו מצרטף ליותר מכריסר עמודים בסך הכול, לא חדל מלהעסיק את המחקר המדעי שנים רבות, ואילו עבודתו המקיפה בפרשנות התלמוד, המהווה את עיקר פרסומו והשפעתו בשעתו ולדורות לא זכה לעיון ביקורתי… [הספרות הפרשנית לתלמוד, ב, עמ’ 32]

Although some serious advances have been seen recently in the field of Ramban’s Talmudic Novella, especially by Dr’s Shalem Yahalom and Yoel Florsheim in their works mentioned in the beginning of this article, however much research still remains to be done.

Daniel Abrams, in an article first printed in the Jewish Studies Quarterly and then updated in his recent book Kabbalistic Manuscripts and Textual Theory (pp.215-218), outlines a project to print a proper edition of Ramban’s commentary on Torah, based upon all extant manuscripts and including all the known super-commentaries written on the work, both printed and those still in manuscript.[8] This would help reach a proper understanding of Ramban’s Pirush. Abrams’s main concern is with reaching a proper understanding of Ramban’s Torat HaKabalah, but as the bulk of the Pirush is not of a kabbalistic nature, such an edition would benefit everyone greatly. Unfortunately due to lack of funds nothing has yet happened with Abrams’s proposal.

Dr’s Ofer and Jacobs’s new work, based on the numerous extant manuscripts of the Pirush has definitely helped us in getting closer to a proper understanding of Ramban’s work on Torah.[9] We can only hope with time Abrams’s proposal will bear fruit.

For information on purchasing this work, contact me at: Eliezerbrodt@gmail.com Copies are available at Biegeleisen in New York. E-mail if you are interested in a table of contents or a PDF of Rabbi Kalman Kahana’s article.

[1] For a useful write up about the importance of the Ramban, see Yisroel M. Ta-Shema , Ha Safrut Haparshnit LiTalmud, 2, pp. 29-55. I am in middle of attempting to write a complete bibliography of all his writings and studies related to everything he wrote.

[3] On the location of Kever Rochel see Kaftor Vaferach [1:246-247; 2:69]; Tevuot HaAretz, pp. 131-135. See also Tosfot HaRamban LiPirusho LeTotrah, pp. 229-233, 287-292

[3] This article of Rabbi Eisenstadt was reprinted recently in his a collection of his writings called Minchat Tzvi, New York 2003, pp. 125-138. The letter of Rabbi Martzbach is also printed there (pp. 139-140) along with Rabbi Eisenstadt response. The letter of Rabbi Martzbach is also printed in Alei Yonah with some additions but without Rabbi Eisenstadt response (pp. 155-157). The Alei Yonah edition does not say to whom the letter was written to. They also edited out his request for a copy of the article.

[4] See also here.

[5] Thanks to Professor Haym Soloveitchik for pointing this out to me.

[6] Megadim 42 (2005), pp. 61-124.

[7] That is besides for the various criticism of the work, beyond the scope of this article. [See this earlier post].

[8] The recent edition of the Ramban printed by Mechon Yerushalayim is a far cry from what needs to be done for this purpose.

[9] See here for another article of Dr. Ofer which demonstrates the benefit of the manuscripts of the Ramban to reach an understanding of the Ramban.