[שאלה] מה פירוש נביא שסדר את התורה עשה זאת בנבואת משה רבינו. האם היו עוד נביאים כמשה? הלא מעיקרי הדת שלא היו.

[תשובה] לפי הרמב“ם אלו עיקרי הדת. ברם, אפילו אמוראים סברו אחרת לגבי הפסוקים האחרונים בתורה

In other words, since there are amoraim who disagree with Maimonides’ Principle, it is not binding.

[7]

In speaking of the Torah, Sherlo uses this provocative formulation (emphasis added):

ניסוח התורה הוא ניסוח שאנו מתייחסים אליו כולו כאילו כולו יצא מרבונו של עולם בדרגת “תורה” ולא בדרגה נמוכה ממנה.

One of the commenters asks as follows (and both of the possibilities he suggests are far from traditional):

הרב כותב כי “ניסוח התורה הוא ניסוח שאנו מתייחסים אליו כולו כאילו כולו יצא מריבונו של עולם”. האם זהו רק יחס שלנו, והיינו שיש לכתוב סמכות של תורה, או שבאמת אלוקים דיבר וסיעתו של עזרא כתבה?

Sherlo replies that he simply does not know, and that we don’t know what the Torah looked like in the years after it was given (until the days when the Torah she-ba’al peh was written down, and quotations of the Torah are found there). In other words, it might be significantly different than the Torah we have today:

אנחנו לא יודעים. יש חור שחור בתולדות מסירת התורה, כי אין לנו בדיוק מושג מה היה באלף השנים שבין מתן תורה לבין כתיבת התורה שבעל פה. לכן התנסחתי בנוסח זה.

In a previous post I already called attention to a comment by the great R. Solomon David Sassoon, who wrote as follows (

Natan Hokhmah li-Shelomo, p. 106 [emphasis in original; I learnt of this passage from R. Moshe Shamah]):

אבל אם יאמר פסוקים אלה נביא אחר כתב אותם מפי הגבורה ומודה שקטע זה הוא מן השמים ומפי הגבורה, אדם שאומר כך אינו נקרא אפיקורוס, מה שהגדיר אותו כאפיקורוס אינו זה שאמר שלא משה כתב את הקטע אלא בזה שהוא אומר שדבר שזה מדעתו ומפי עצמו אמרו ושאין זה מן השמים

This too can provide a religious justification for Biblical Criticism.

Let me make one more comment relating to Biblical Criticism. (There is, of course, more to say, but this can wait until the next installment.) Those who have read my posts know that I find it very interesting when Orthodox figures attack a position as foolish or heretical not knowing that this very position was stated by a great sage. If one was dealing with a detached academic, obviously heresy wouldn’t be a concern. And as for regarding a position as foolish, even if it is pointed out to the detached academic that, for example, Aristotle held this view, he would not retract from his statement that the position he criticized was foolish. It would just be an example where the great Aristotle adopted a foolish position. But in the Torah world, this sort of attitude is improper, so people are in a bind when they learn that the position they thought was foolish was actually held by a great sage.

[8] In many cases I assume the people cannot change the way they think. They still think the position is foolish, but they can’t say this publicly anymore. Let me given an example of this relating to Biblical Criticism.

As is well-known, one of the arguments of early Biblical Criticism was that the “Book of the Law”, found by Hilkiah and given to Josiah (see 2 Kings 22 and 2 Chronicles 34), was actually the book of Deuteronomy, which the Critics assume to be the latest of the books of the Pentateuch.

[9] They regard it as a pseudepigraphical document, attributed to Moses. In other words, it was a pious fraud created to provide the basis for Josiah’s reform. Readers can correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t think that this theory has many advocates in recent scholarship. In any event, what concerns me here is that when rabbis and polemicists argue against Biblical Criticism, they often tear part the claim that Deuteronomy is the subject of the Josiah story. One can find lectures online where the speaker will mention this notion, and then reject it with great contempt. The attitude expressed is that anyone with any understanding of the Torah, or even of simple

peshat of the relevant verses, would realize that Josiah story must be dealing with a complete Torah, not one book of the Pentateuch. Some go so far as to make it seem that only an idiot could conclude that Josiah is dealing with the book of Deuteronomy. For a traditionalist, this would appear to make perfect sense, since who ever heard of dividing the Torah into separate scrolls?

[10]

Yet if the people arguing so strongly against the Josiah-Deuteronomy connection would look at the version of the story in 2 Chron. 34, they would find something that would shock them. While verses 14 and 15 speak of finding ספר תורת ה’ ביד משה and ספר התורה, the commentary attributed to Rashi understands this to mean משנה תורה, i.e., the book of Deuteronomy! In other words, the position of the Bible Critics as to which book was “found”,

[11] and the position attacked so mercilessly by the opponents of the Biblical Critics, is in fact held by a

rishon! I am not saying that this

rishon is a proto-Biblical Critic, or that he denies the Mosaic authorship of Deuteronomy. But he does say that the book found, and which was read to Josiah and so affected him, was not the Torah itself, but only the book of Deuteronomy. I grant that this is an unusual position, but now that we have seen what this

rishon holds, does this mean that this viewpoint now has to be treated with more respect, as opposed to the current treatment it gets at the hands of Orthodox polemicists?

[12]

This notion, that the book Hilkiah found was Deuteronomy, is also advocated by R. Elijah Benamozegh.

[13] Benamozegh states that if this viewpoint is correct, it means that from early on there was a practice to write the book of Deuteronomy separately from the rest of the Pentateuch. He also cites a rabbinic view that the Torah that the king carried was only the book of Deuteronomy.

[14] Based upon this, he explains why the book found was brought to the king, since it was precisely this book that the king was obligated to write and carry with himself. Benamozegh concludes:

סוף דבר קרוב ונראה שהיו מעתיקים ס’ מ”ת בפ”ע כמו שנוכיח להבא בע”ה כי ספר תורת משה נכתבה בימי קדם חלקים ונתחים כל א’ בפ”ע, ובראש כל אתוון מה שהעידו רבותינו באומרם: תורה מגלה מגלה נתנה

2. Since in the previous section I referred to Ibn Ezra’s view on post-Mosaic additions to the Torah, let me say a little bit more about this. At the beginning of his commentary to Deuteronomy chapter 34, Ibn Ezra states that the last twelve verses of the Pentateuch were written by Joshua. The Talmud only offers this possibility concerning the last eight verses. The Kol Bo, Seder Tefillat ha-Moadot (ed. Avraham [Jerusalem, 1992), vol. 3, p. 220) writes:

ושמנה פסוקים אשר בזאת הברכה שהם מויעל משה עד ויהושע בן נון, יחיד קורא אותם.

The problem with this formulation is that there are twelve verses from ויעל משה (Deut. 34:1), not eight. I presume that instead of ויעל משה the text should read וימת משה (Deut. 34:5), which is the eighth verse from the end and what the Talmud refers to. It is also possible that instead of stating “eight verses” it should read “twelve verses,” and the

Kol Bo would then be agreeing with Ibn Ezra.

[15]

In

The Limits of Orthodox Theology I referred to

Avat Nefesh, an anonymous medieval commentary on Ibn Ezra, as one of those who understood the latter as positing post-Mosaic additions. I had access to the Genesis portion of the commentary which appeared in William Gartig’s 1994 Hebrew Union College doctoral dissertation. A typescript of the complete commentary is now available on Otzar ha-Hokhmah, and this typescript pre-dates 1994. (In the preface to the typescript, the transcriber presents evidence that the author is R. Yedayah ha-Penini [ca. 1270-1340].)

[16] In his commentary to Gen. 12:6,

Avat Nefesh states that according to Ibn Ezra “many verses” in the Torah were only added after Moses’ death. He also notes that this is the focus of most of Ibn Ezra’s “secrets”.

כי כונתו שזה לא כתב משה אך נכתב אחר שנכבשה הארץ וכן דעתו בהרבה פסוקים ורוב סודותיו סובבים בזה כאשר אמר בראש אלה הדברים.

With the complete commentary we can also see what he says in Deut. 1:1. Here again he explains Ibn Ezra’s secret to be referring to post-Mosaic verses. Yet he also expresses his disagreement with Ibn Ezra and defends Mosaic authorship, although it is not clear if he is disagreeing in general or only with regard to the example he is discussing, where he explains why the expression בעבר הירדן is not an anachronism.

The principle by which Ibn Ezra determined that certain verses are post-Mosaic is if they contain what he regarded as clear anachronisms. All of the examples he gives in his commentary to Deut. 1:1 fall into this category. R. Joseph Bonfils famously argues that while Ibn Ezra acknowledged post-Mosaic additions of individual words and verses, which function as explanatory glosses, Ibn Ezra did not believe that there could be entire sections that are post-Mosaic. This is how Bonfils explains why Ibn Ezra, in his commentary to Gen. 36:31, responded so sharply to Yitzhaki’s suggestion that Gen. 36:31-39 is post-Mosaic:

וחלילה חלילה שהדבר עמו . . . וספרו ראוי להשרף

The problem with these verses is that they begin with the following: “And these are the kings that reigned in the land of Edom, before there reigned any king over the children of Israel.” Some viewed it is an anachronism to speak of the Israelite monarchy when still in the desert. As mentioned in The Limits of Orthodox Theology, R. Judah he-Hasid, R. Avigdor Katz, and according to one Tosafist collection also Rashbam identified these verses as post-Mosaic. As far as I can tell, there is no evidence to support Bonfil’s supposition that Ibn Ezra, for dogmatic reasons, denied that there could be post-Mosaic additions of entire sections. In the case of Gen. 36:31-39, there are internal reasons why Ibn Ezra would not see it as problematic, as he explains in his commentary.

Returning to Avat Nefesh, there is something else noteworthy in the commentary. He mentions that Ibn Ezra believes that “many verses” are post-Mosaic. Although Ibn Ezra himself doesn’t supply us with that many verses, once we assume that Ibn Ezra was guided by what he viewed as anachronisms in pointing to post-Mosaic additions, there is no reason to conclude that the examples he gives in his commentary to Deut. 1:1 exhaust the list. In support of Avat Nefesh’s point, let me mention the following: Ibn Ezra lists Gen. 12:6, “And the Canaanite was then in the land,” as one of the post-Mosaic additions. Understood according to their simple sense, these words can be seen as anachronistic as the Canaanites were still in the Land of Israel in the days of Moses. In other words, the words are written from the perspective of one living in a generation when there were no longer Canaanites in the Land of Israel. If these words are post-Mosaic, then the second half of Gen. 13:7 must also be post-Mosaic, as it says, “And the Canaanite and the Perizzite dwelt then in the land.” Just as Ibn Ezra didn’t feel it was necessary to spell out his view with regard to Gen. 13:7, so too, Avat Nefesh believes, there are other similar cases.

Avat Nefesh provides an example of this in his commentary to Num. 13:24, where he writes that according to Ibn Ezra (see his commentary, ibid.) at least some of what appears in this verse was written in the days of the Judges.

ר”ל שוירדוף עד דן נכתב לפי דעתו בימי השופטים שאז נקרא שם העיר דן כשם דן אביהם, כן כוונתו בנחל אשכול שנכתב אחרי כן בשמו שקראו הקורא

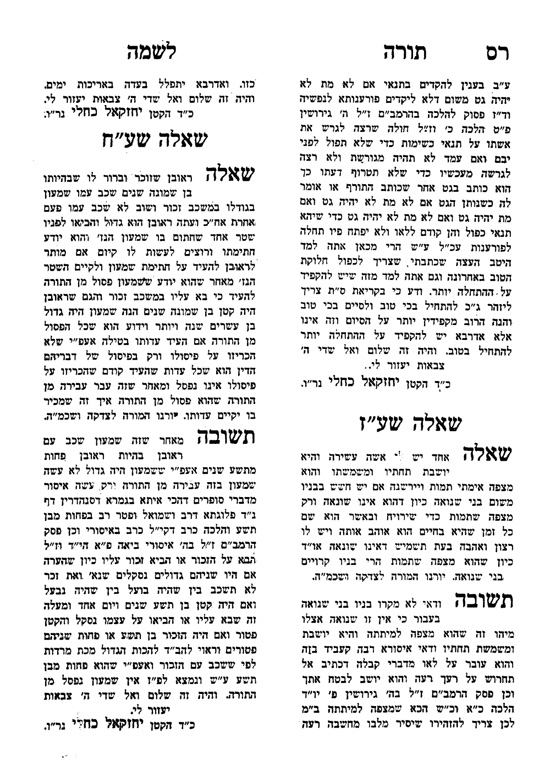

4. In a recent post on his blog, R. Daniel Eidensohn refers to my comment in this

post where I suggested that the lenient attitude towards pedophilia in much of right wing Orthodoxy is due to the fact that the real trauma of sexual abuse is not something that one can learn about in traditional Jewish sources but comes to us from psychology, and as such is suspect in those circles that see psychology as a “non-Jewish” discipline. Let me offer another example that illustrates how today we take sexual abuse much more seriously than in previous years. Here is a responsum no. 378 from R. Joseph Hayyim’s

Torah li-Shemah.

As you can see, the sexual abuse of a child under nine years old was not regarded by him as an earth-shattering violation (certainly not at the level of violating Shabbat or eating non-kosher food). While we regard child sexual abuse as one of the worst things imaginable, it is easy to see how someone whose only exposure to these matters would have been through traditional sources would not see it as such a terrible offense, namely, an offense that would require one turn the person into the police. In another responsum, Torah li-Shemah no. 441, R. Joseph Hayyim writes as follows regarding one who has sex with a child under nine years old:

והרי זה הבועל כמי שמשחית זרעו ע”ג עצם ואבנים

In other words, he sees this as an issue of wasting seed, without any cognizance of the terrible damage done to the child.

[18] Responsa like this are important in showing how, with increased knowledge, attitudes have changed. What our generation regards as the most vile behavior was often seen in a very different light in previous generations. This is the only

limud zekhut for those who in past years did not take sexual abuse seriously.

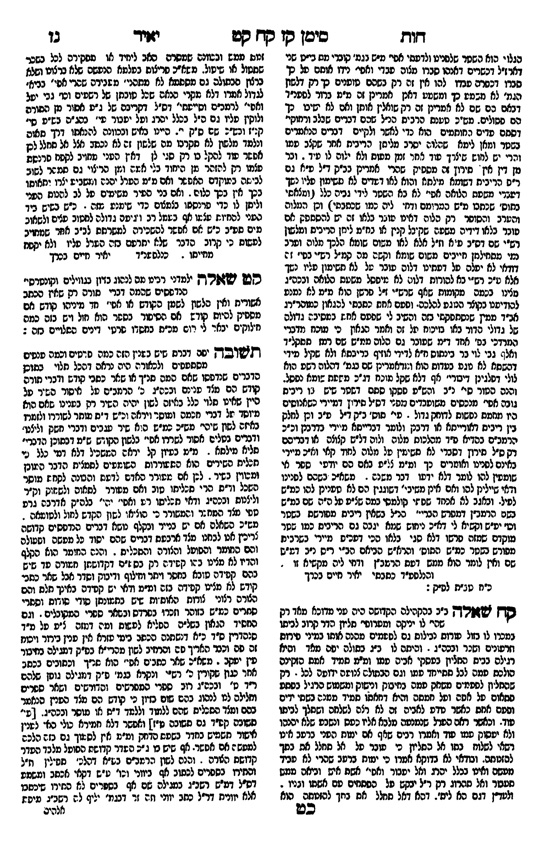

R. Ysoscher Katz also called my attention to a relevant discussion on a Yiddish site. See

here. One of the matters discussed is a responsum of R. Yair Hayyim Bacharach,

Havot Yair no. 108.

I think any modern person reading it will be surprised to see that there is no emotion shown, no reflection on the difficult circumstances of the girl. Everything is examined from a halakhic standpoint. But this again shows how differently we approach these sorts of matters than was the case years ago.

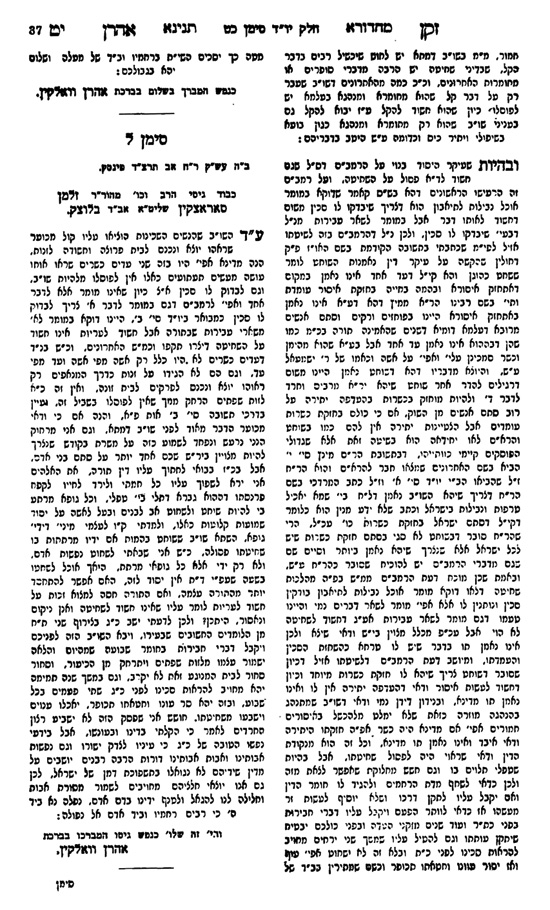

If sexual abuse is treated just like another sexual transgression, then the lenient approach some rabbis have adopted towards it makes sense. After all, shouldn’t a rabbi want to give a sinner the opportunity to repent? Sexual sins have always been regarded differently than kashrut or Shabbat violations. If a rebbe was seen eating a hamburger in McDonalds or driving on Shabbat he would immediately be fired, without any opportunity to repent. But more leeway is given when it comes to sexual sins, the reason being, no doubt, that everyone understands the power of the evil inclination in this area. A good illustration of my point is seen in R. Aaron Walkin, Zekan Aharon, vol. 2, no. 30.

The responsum deals with a shochet who was seen entering the home of a “loose” woman. R. Zalman Sorotzkin didn’t know what do about it and wrote to R. Walkin. R. Walkin refuses to disqualify the shochet, and tells R. Sorotzkin that even if there were two witnesses testifying to the matter it would not change his mind, since this would only turn the shochet into a

mumar le-davar ehad! It is true that not all rabbis would have been as lenient as R. Walkin,

[19] but the fact that this great posek ruled the way he did is quite significant.

[20]

Finally, I am curious to hear what some of the lawyers reading this post have to say about the following: Some time ago, I was contacted by a man who wanted to talk to me about being an expert witness for the defense in the appeal of a sexual abuse conviction. The case is actually one of the worst we have seen. I was told that my role would only be to answer questions about sexual mores in the hasidic world, in particular, how they understand tzeniut. While I am far from an expert on this, not being from that world, the defense team wanted an academic on the stand. (Needless to say, there are academics who would also be much better choices than me.) .

Nothing came of this discussion, and I myself decided that I would have nothing to do with the case after learning the particulars, which are indeed sickening. My question is as follows: We know that defense lawyers are not personally tainted even if they represent horrible people. We recognize that this is their job. My sense is that people would not give the same leeway to an expert witness, and he would be viewed very negatively, as one who was helping to free a sexual abuser. Yet I would like to get some feedback from the lawyers. If I would have agreed to be called to the stand to answer general questions about halakhah and tzeniut, does the fact that I was part of the defense team’s strategy mean that I would be “helping” the defense? It was made clear to me that my role would be to simply to answer general questions and I would have nothing to do with the defendant per se. Another way of framing the question is, would it have been immoral for me to agree to this role if, after having examined the evidence, I was convinced that the defendant committed terrible crimes and should remain in jail?

5. For the runoff quiz I asked the following:

A. What is the first volume of responsa published in the lifetime of its author?

B. There is a verse in the book of Exodus which has a very strange vocalization of a word, found nowhere else in Tanach. (The word itself is also spelled in an unusual fashion, found only one other time in Tanach). The purpose of this vocalization is apparently in order to make a rhyme. What am I referring to?

Some got the answer to the first question, and others got the answer to the second question. But only one person, Peretz Mochkin, got the answers to both.

The answer to the first question is the responsa volume Binyamin Ze’ev (Venice, 1539), by R. Benjamin Ze’ev of Arta.

The answer to the second question is the word אתכה in Ex. 29:35. It is spelled and vocalized the way it is in order to rhyme with the word ככה that appears earlier in the sentence.

וְעָשִׂיתָ לְאַהֲרֹן וּלְבָנָיו, כָּכָה, כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר-צִוִּיתִי, אֹתָכָה

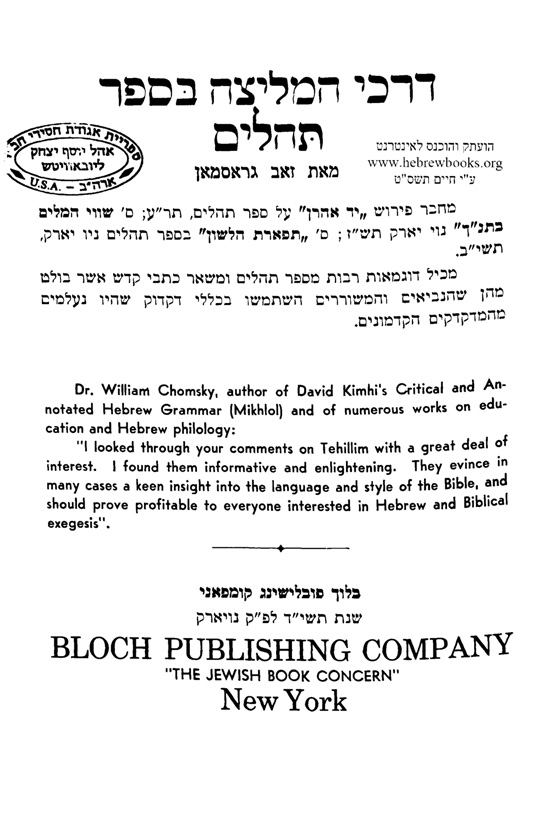

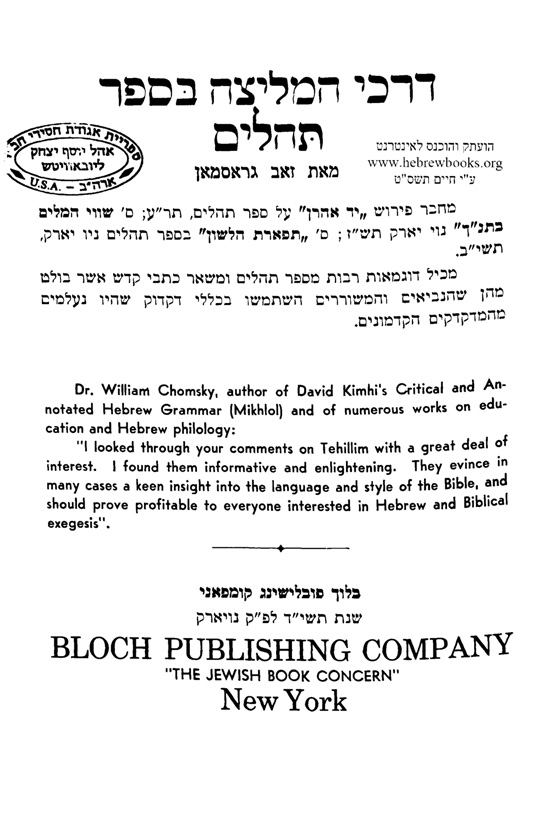

One of the sources that refers to this text is Zev Grossman,

Darkhei ha-Melitzah be-Sefer Tehillim. This is a very interesting book on aspects of grammar in Tanach. Here is the title page, with an approbation of sorts from William Chomsky. I don’t know of any other book that puts the approbation on the title page, and in this case the approbation is in English. (William Chomsky, incidentally, is the father of Noam Chomsky.)

One of the things Grossman points out in his book is that there are many examples of verses where we find words in non-grammatical forms in order that they rhyme. Here is just one example, from Psalms 5:8:

וַאֲנִי–בְּרֹב חַסְדְּךָ, אָבוֹא בֵיתֶךָ; אֶשְׁתַּחֲוֶה אֶל-הֵיכַל-קָדְשְׁךָ, בְּיִרְאָתֶךָ

In context, the final word, ביראתך, means “in fear of you”, even though this is not grammatically correct. This form is used to make the rhyme, because if one were applying grammatical rules it would not be spelled this way.

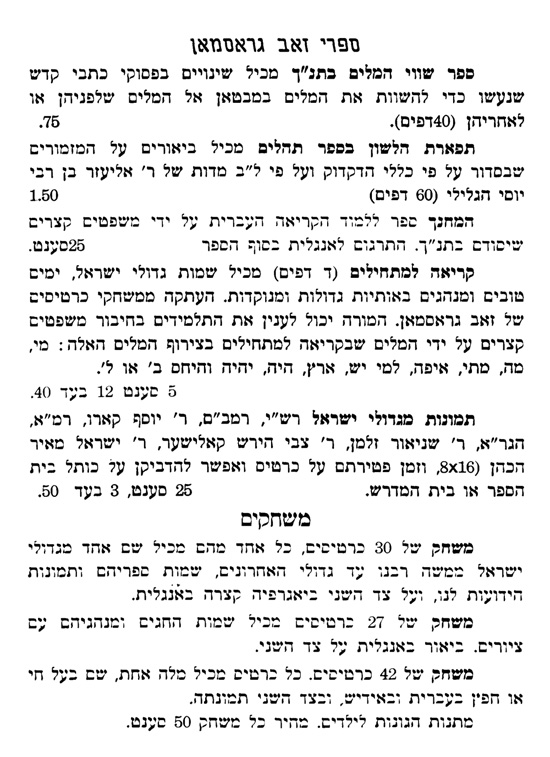

At the end of the Hebrew section of the book, Grossman has a page listing his published books.

As you can see, he also produced a set of gedolim cards. When I was young, in the 1970s, there were gedolim cards. I know this because I collected them.

[21] But I never imagined that they existed already in the early 1950s.

6. In my post of January 13, 2013, I wrote: “R. Meir Schiff (Maharam Schiff) is unique in believing that one without arms should put the tefillin shel yad on the head, together with the tefillin shel rosh. This is the upshot of his comment to Gittin 58a.” I saw this comment of Maharam Schiff many years ago, and unfortunately did not examine it carefully before adding this note. As R. Ezra Bick has correctly pointed out, Maharam Schiff is not speaking about wearing tefillin shel yad on the head to fulfill the mitzvah, but only stating that this is a respectful way to carry the tefillin shel yad if you have to remove it from your arm. This has no relevance to what I wrote about someone without arms (unless he has to carry the tefillin shel yad).