Borders, Breasts, and Bibliography

By Elliott Horowitz

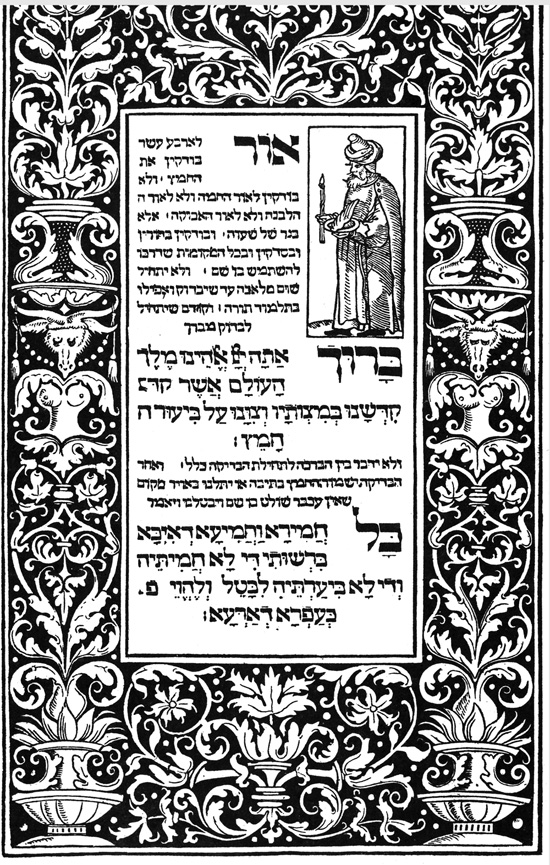

Dan Rabinowitz has provided us which a characteristically learned pre-Passover post on the Prague 1526 Haggadah, specifically concerning the illustrations on its borders, and from those borders continues on to the always contentious subject of breasts, a bare set (or rather, two bare sets) of which he claims may be found on the title page of that edition. Indeed, on both the right and left borders of the title page may be found rather curious figures with non-human faces but quite human- looking breasts; yet those breasts are not bare, but rather bound in form-fitting corsets from which the nipples peek out. Readers may search on their own, online or elsewhere, for images of such nipple -revealing bodices, which were popular in English masque costumes of the early seventeenth century,[1] but I will provide only a quotation from the celebrated English traveler Fynes Moryson (1566-1630) on the women of late sixteenth-century Venice who “weare gowns, leaving all of the neck and brest bare, and they are closed before with a lace….they show their naked breasts, and likewise their dugges, bound up and swelling with linnen, and all made white by art.”[2]

Here is the title page::

From the breasts on the borders of the Prague Haggadah’s title page Rabinowitz moves on to the less contentious pair to be found in the Haggadah itself, appropriately accompanying the quotation from Ezekiel 16. He charitably notes that “both Charles Wengrov and Elliot[t] Horowitz have pointed to earlier manuscript antecedents of Prague’s usage of such illustrations,” but then takes issue with “Hor[o]witz’s contention that Spanish Jews were less accepting of such displays.” To that end he presents, in living color, two panels from the so-called “Sarajevo Haggadah,” illustrated in fourteenth-century Spain, depicting “a bare-breasted Eve,” and another illustration from the “Golden Haggadah,” – of similar provenance – depicting female bathers in a scene of the finding of Moses.

Yet in all those instances the semi-nude women are shown either in profile with partially covered breasts, or with breasts of rather adolescent dimensions – in contrast to the more amply-bosomed maiden depicted frontally in the Prague Haggadah (and uncensored facsimiles thereof), but not in Rabinowitz’s otherwise amply illustrated post. Moreover, in contrast to the rather demure female figures in the late medieval Spanish haggadot, the “Prague Venus” (as I shall call her) gazes directly at the viewer – in a manner reminiscent of Titian’s “Venus of Urbino,” completed a dozen years after the 1526 Haggadah was published. It may be noted that two bare-breasted mermaids are frontally depicted on a bronze Hannukah lamp from sixteenth-century Italy in the Israel Museum’s Stieglitz collection.[3]

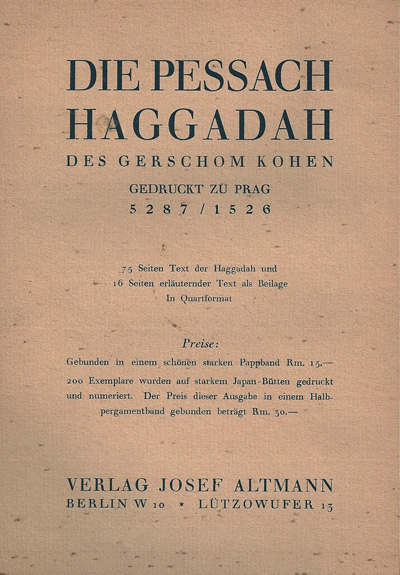

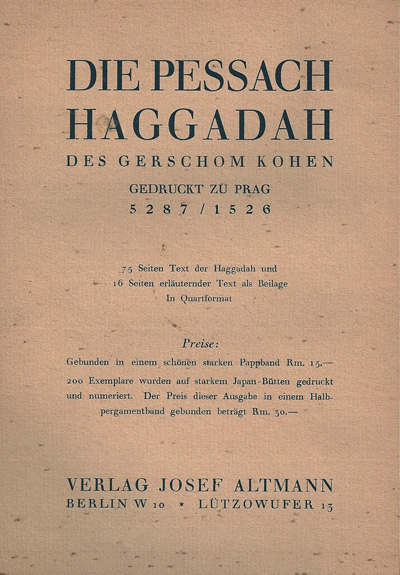

As far as the Prague Haggadah’s date, Rabinowitz (gently) chides me for taking Efrat’s Religious Council to task not only for deleting the semi-nude scene from the 2001 facsimile edition in honor of their settlement’s twentieth anniversary, but for giving the Haggadah’s date as 1527 rather than 1526. Rabinowitz justifies that error by noting that the (uncensored) Berlin facsimile – whose date he gives erroneously as 1925 rather than 1926 – gave the Haggadah’s date as “5287/1527.” This is indeed true of its frontispiece, but in my battered copy of the Berlin facsimile a previous owner helpfully left behind a double-side flyer for the Haggadah which includes the more accurate information: “GEDRUCKT ZU PRAAG, 5287/1526.”

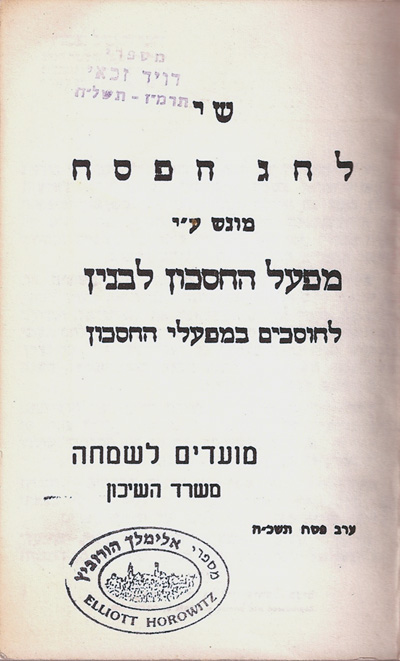

In my modest collection of haggadot the Berlin facsimile of the Prague Haggadah sits next to an octavo-size paperback of that same Haggadah issued in 1965 by Israel’s Ministry of Housing. It’s frontispiece reads:

שי לחג הפסח מוגש ע”י מפעל החסכון לבנין

לחוסכים במפעלי החסכון

Although the date of the Haggadah is there too given erroneously as 1527, Israel’s Mapai-controlled Housing Ministry of 1965 saw no reason to make the same breast-related deletions as Efrat’s Religious Council thirty six years later – or perhaps did not yet have (or afford) the technical ability to do so. The minister of housing before Passover of that year was Yosef Almogi, who had been general secretary of Mapai during the early 1960’s but joined Ben-Gurion’s renegade Rafi party before the November elections of 1965, after which he was replaced by Levi Eshkol. The copy in my possession previously belonged to David Zakkai (1886-1978), who was briefly general secretary of the Histadrut before David Ben-Gurion assumed that position in 1921, and after the founding of Davar in 1925 wrote for that newspaper for many years under the pen-name “Z. David.” He won the Sokolov prize for journalism in 1956. Some three decades later many of the books previously in his possession were being sold off as duplicates by the library of Ben-Gurion University, which was named after yet another Mapai politician – Zalman Aranne (1899-1970), who had also been general secretary of the party, and later served( twice) as Israel’s secretary of education and culture.

The old days of Mapai dominance are well behind us, but so are the days when Israel’s housing ministry could reprint a Haggadah showing bare breasts. As I write, the newly installed minister of housing is Uri Ariel of the Jewish Home, whose predecessor was a member of Shas. Perhaps the additional funds that are now expected to come Efrat’s way will allow its Religious Council to put out another facsimile edition celebrating yet another expansion of that venerable settlement. My own suggestion is Ze’ev Raban’s illustrated Shir ha-Shirim, also suitable for Passover, but not yet available in a kosher edition. It will certainly keep their censorship committee busy.

[1] See recently Barbara Ravelhofer, The Early Stuart Masque: Dance, Costume, and Music (2009).

[2] F. Moryson, An Itinerary…(1617, reprint 1907-8), recently quoted in M. F. Rosenthal, “Cutting a Good Figure…,” in M. Feldman and B. Gordon eds. The Courtesan’s Arts: Cross-Cultural Perspectives (2006), 61. See there also illus. 2.2.

[3] For reproductions of the image see Chaya Benjamin ed.,

The Stieglitz Collection: Masterpieces of Jewish Art (1987), 157; Elliott Horowitz, “Families and their Fortunes: The Jews of Early Modern Italy,” in David Biale ed.,

Cultures of the Jews (2002), 578.

Appendix by Dan Rabinowitz:

In addition to the censored reproductions discussed in the post and the one provided by Elliott Horowitz, we provide an additional example in this ever growing genre. One of the more well-known series that reproduce facsimile haggadot are those published on behalf of the Diskin Orphan Hospital Ward of Israel. As a fundraiser, they publish and distribute a different reprint of an earlier haggadah both print and manuscript. (See here discussing the Washington Haggadah reprint that led to accusation of heresy ). The first haggadah reprinted in this series is the Prague 1526. But, there are numerous errors and significant omissions in this reproduction. First the title, “The First Known Printed Passover Haggadah by Gershom Kohen Prague 5287/1527.” This edition of the haggadah is not the first known printed haggadah, that is likely circa 1486, by Soncino (see Yerushalmi, Haggadah & History, plates 2-3; Issakson, no. 29), and the first illustrated is the 1512 Latin. In the introduction written by Dr. Aaron Rosmarin, he offers that Prague 1526 is “the oldest printed Hagadah graced with woodcuts.” Again that is wrong. The 1486 haggadah already includes a handful of woodcuts.

Instead, at best, Prague 1526 is the first fully illustrated haggadah for a Jewish audience. The title also contains an error regarding the secular date, giving it at 1527. Rosmarin compounds this error. First he hedges on the secular year, when he explains that this editions was “printed by Gershom ben Shlomoh ha-Kohen and his brother Gronem in Prague 1526/27” but then zeros in on exactly when it “was completed on Sunday, the 26th of the month of Teves, 5287 (in January 1527).” It was December 30, 1526 and not some time in January 1527.

Additionally, regarding the nude image accompanying Ezekiel 16:7 that is omitted in its entirety. Although this omission (as well as a two other seeming non-offensive images) is not noted in the introduction, Rosmarin is careful to explain (without irony) that the 1526 edition contains some minor textual variants and omits the songs Ehad mi Yodeh and Had Gadyah, therefore this facsimile is not being reproduced to be used at the seder as “there are Hagadahs in abundance” for that purpose. Instead, the reason for reproducing Prague 1526 is because “this Hagadah is of great value for its art and uniqueness.”