Emek ha-Netziv : The Manuscript

Emek ha-Netziv : The Manuscript

by Gil S. Perl

Rabbi Dr. Gil S. Perl is dean of the Margolin Hebrew Academy/Feinstone Yeshiva of the South in Memphis. The following selection comes from his new book, The Pillar of Volozhin: Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin and the World of Nineteenth-Century Lithuanian Torah Scholarship.

The manuscript of ‘Emek ha-Netziv remains in the possession of the Shapira family and there are no additional extant copies. The family are prominent members of a staunchly traditionalist Ḥaredi community in the Geulah neighborhood of Jerusalem. Members of this community generally oppose sustained contact with Western culture and its representative institutions, including universities of any type. The Shapira family seems to harbor additional skepticism toward those researching Netziv , due to the fact that his relative openness to certain aspects of non-traditional culture has made him a controversial figure in some ultra-Orthodox communities.[1]These facts, combined with the sheer value of their manuscript collection,[2] make the family understandably guarded about allowing access to thematerials they possess. However, with the assistance of Rabbi Zevulun Charlop, Dean of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in New York City and a cousin of the Shapira family,[3] I was able to secure brief and accompanied access to the manuscript from which ‘Emek ha-Netziv was taken.[4]

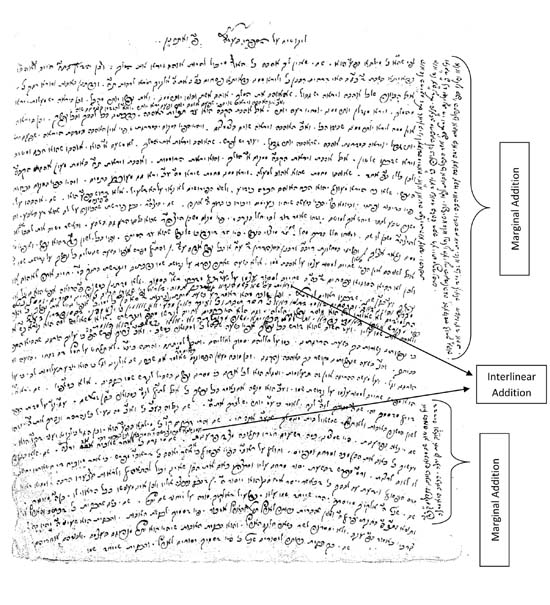

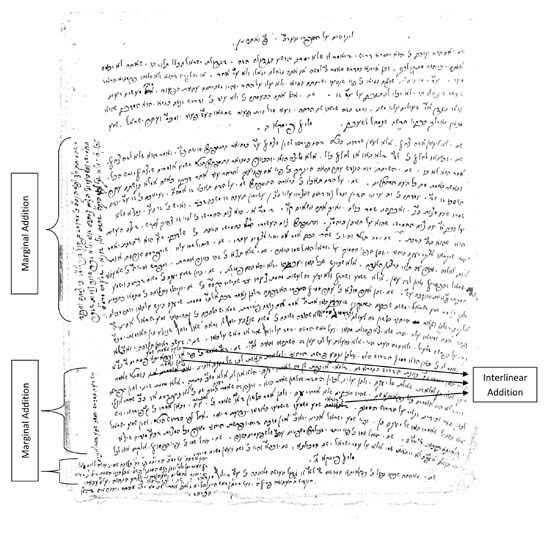

The manuscript is handwritten in three volumes, corresponding to the three volumes of the printed text. The first two volumes were bound, but the binding has completely deteriorated and sections of each volume easily separate from one another. The third volume seems never to have been bound. The pages of all three volumes are severely frayed at the edges.

As suspected, the manuscript contains a core text with countless interlinear and marginal additions as well as words and entire lines that have been crossed out:

.

It is important to note that the brackets and parenthesis which appear throughout the printed text do not correspond to these additions. Rather, they correspond to places in which Netziv placed parenthesis or brackets around his own words both in the core text and in the additions. The additions and the notes he appended to the end of the manuscript (referred to by the Netziv as hashmatot )[5] were incorporated without indication into the printed text.

The script of the core text through the first two volumes and half of the third is a fairly consistent narrowly-spaced brown cursive[6] written with a fairly wide-tipped pen. In the second half of the third volume the script of the core text changes to a blacker, wider-spaced cursive seemingly done with a thinner-tipped pen. The script of the later marginal additions varies.

The script of the core text through the first two volumes and half of the third is a fairly consistent narrowly-spaced brown cursive[6] written with a fairly wide-tipped pen. In the second half of the third volume the script of the core text changes to a blacker, wider-spaced cursive seemingly done with a thinner-tipped pen. The script of the later marginal additions varies.

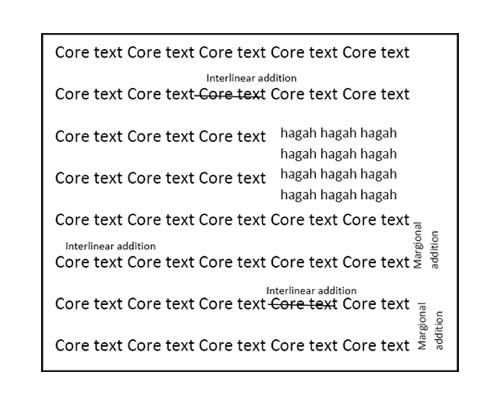

The notes which appear scattered throughout the printed text (referred to by the Netziv as hagahot) were written at the same time as the core text,[7] as evidenced by the identical script used and the intentional indentations left in the text of the core commentary in order to create space for the hagahot. The hagahotalso contain marginal additions. A typical page in the manuscript containing hagahot, then, is represented in the following diagram:

The reference to the newly printed book ‛Emek Halakhah mentioned above appears as an interlinear addition to the core text, thus implying that for that particular section of the commentary on Naso, the core text was written prior to 1845 and the addition was included after 1845. The references to Reb ‘Iẓele are also found in the core text with the word “she-yiḥyeh,” which dates those passages of the core text to the years prior to 1849 as well.[8]

The orderly progression of chapters in the core text, which begin at varying places on the physical page of the manuscript, indicates that Netziv wrote down his comments in this manuscript in proper sequence, following the order of Sifre. [9]That is, one can safely assume that in this particular copy of the manuscript, the core text of Netziv’s comments on Parashat Bamidbar were committed to writing before those of Parashat Naso, and his comments on pesikta’ aleph were committed to writing prior to those of pesikta’ bet.[10] If the core text of the manuscript was written sequentially, and the core text of EH Naso 49 (I:181) was necessarily written prior to the publication of Zev Wolf ben Yehudah Ha-Levi’s 1845 publication of ‘Emek Halakhah, one can deduce that, at the very least, the entire core text until that point was also committed to writing prior to 1845. Likewise, from the appearance of the word “she-yiḥyeh” in the core text of Be-ha‛alotekha andShelaḥ[11] one can assume that the text up to that point was written prior to Reb ’Iẓele’s death in 1849. If we then add that the handwriting remains rather constant in the core text until the second half of the third volume, we have reason to believe that all of the core text until that shift in appearance was committed to writing prior to 1849.

Thus, one can safely conclude that a good portion of the printed edition of‘Emek ha-Netziv was indeed written while Netziv was a young man in his twenties and thirties. As such, the general character and main attributes of the work must be seen as a product of the cultural and intellectual atmosphere of Lithuanian Jewish society in the 1830s and 1840s. At the same time, given the large number of later additions and the lack of any demarcation in the printed text, one can not firmly ascribe a date to any specific passage found in it, with the exception of those which contain explicit or implicit references to the time of composition.

Censorship

The process of preparing ‘Emek ha-Netziv for publication was painstakingly performed by the Shapira family over the course of many years, and thus the printed text seems to be relatively free of printing errors. However, there are two hints in the printed text which suggest the possibility of editorial censorship.

As noted above, Netziv’s relative openness to sources of information beyond the pale of the current traditionalist canon is a character trait which is at odds with the values of the contemporary ultra-Orthodox community. As we will describe at length in the pages that follow, ‘Emek ha-Netziv is filled with citations and references to such sources of information. On two such occasions the reference found in the printed text appears to be intentionally altered so as to prevent proper identification of the source. In his comments on ‘Ekev, Netziv writes that for further study one should consult the book called “thirty-two Middot of [sic] in Vilna.”[12] In all probability Netziv is referring to the book published in 1822 called Netivot Olam: Beraita de-32 Middot with the commentary of Ẓvi Hirsch Katzenellenbogen. Katzenellenbogen is known to have been a member of Vilna’s more “enlightened” circles.[13] As such, the possibility exists that the publisher intentionally left out Katzenellenbogen’s name. This prospect is bolstered by the fact that the manuscript contains a name in the standard acronymic form where the printed edition has a blank space. When I asked to look at this reference in the manuscript, it was reviewed by two members of the Shapira family and I was denied permission to look at it. Nonetheless, I did manage to see what seemed like a legible acronym ending in the letter qof.[14] Although it is possible that the editor could not discern the letters of the acronym, if such had been the case one would expect a bracketed editorial note, such as those which appear on several occasions in the printed text where the manuscript is illegible due to stains or frayed edges.[15]

The second possible instance of editorial censorship concerns a passage in Netziv’s commentary on Shoftim which refers the reader to “hakdamat ḥumash besau[16] ve-‘tav’’alef’.”[17] The most common referent for the initials tav”alef in the context of Torah commentary is Targum Onkelos, the ancient Aramaic translation of the Bible. However, if the bet of the word “besau” is replaced with adaled so as to read “desau” we might suggest that the tav”alef stands for targum Ashkenaz, German translation, rather than Targum Onkelos. As such, the citation would be of the well-known introduction to Moses Mendelssohn’s Torah commentary, which was printed in Dessau and contains a German translation of the biblical text. The fact that the subject matter under discussion in this passage of Netziv’s commentary correlates to subject matter discussed by Mendelssohn in the introduction to his Bible commentary supports the latter suggestion.

We might raise the question, then, as to whether the printed text was intentionally manipulated so as to prevent easy identification of Mendelssohn’s work or whether the daled of Dessau was simply mistaken as a bet by the printsetter.[18]The fact that this particular citation was underlined in pink pencil in the manuscript bolsters the suspicion that the publishers of ‘Emek ha-Netziv were sensitive to the potential controversy the citation of Mendelssohn might have caused in the ultra-Orthodox community and that they therefore intentionally altered the printed text.[19]

Both of the above instances of possible censorship beg the question as to why the references were included altogether if the printers wished them to remain unidentified. Furthermore, as will be discussed below, the printed text of ‘Emek ha-Netziv contains references to numerous other works that lie well beyond the traditional contemporary ultra-Orthodox canon which were not censored. As such, the evidence for editorial censorship cannot be considered conclusive. Nonetheless, these two passages do raise the possibility that other parts of the text were more cleverly censored or that other citations were completely deleted.

The End of ‘Emek ha-Netziv

The end of Netziv’s commentary on Sifre, as it appears in the printed edition of ‘Emek ha-Netziv , is also an issue of concern to the critical reader. The commentary in both the printed edition and the manuscript comes to an abrupt halt halfway through the parashah of Ki Teẓeh[20] and well before the end of the text of Sifre itself. One is therefore led to question whether Netziv truly ended his commentary there, or whether there was more to the commentary that does not appear in the printed text.

Several factors indicate that Netziv’s commentary did, in fact, extend beyondpiska’ 27 of Parashat Ki Teẓeh.[21] To begin, Netziv starts his commentary at the beginning of Sifre with an introductory double couplet, and thus one would expect a similar poetic composition at the end of the work, but none appears in the printed text or in the manuscript. Furthermore, a statement of completion marks the close of each parashah throughout the text, but none appears at the end of Parashat Ki Teẓeh. Likewise, the completion of the Book of Numbers is marked by two rhyming stanzas of nine lines each,[22] while Deuteronomy, and the commentary as a whole, has no formal conclusion at all.

One must entertain the possibility that the abrupt ending of the work suggests not that the final portion of the commentary is missing from the printed text but that Netziv never completed the commentary. This theory might be supported by the fact that the statements of conclusion which follow everyparashah are in poetic form in the first two volumes, whereas in the third volume, which consists of the Book of Deuteronomy, the statements consist of nothing more than “Piska’ 8 is complete and [so too] the entire portion of ve-’Etḥ anan.”[23] One might interpret this phenomenon as suggesting that the final touches, such as the transformation of abrupt closing statements into clever couplets, were never applied to the third volume of the work.

Such a conclusion seems unlikely, however, when one considers the numerous revisions and recensions to which Netziv subjected the rest of the commentary. One generally does not spend the time editing, expanding, and re-copying a work that one has yet to complete. Furthermore, in his introduction toHa‘amek She’elah Netziv regrets that he has not yet brought his commentary onSifre to press, but he makes no mention of not having completed writing the text. Similarly, in a comment found in his Harḥev Davar, published along with his Ha‛amek Davar in 1878, Netziv writes that while he has not elaborated on a particular point in this work, he will do so at length when God grants him the merit of “publishing the commentary on Sifre.”[24] Here too, Netziv does not ask for God’s help in finishing the work, but in bringing it to press. Likewise, Avraham Yiẓḥak Kook, one of the outstanding students of Netziv , publically called upon his teacher to publish his Sifrecommentary in a footnote to a biographical article on Netziv published in 1888.[25]He too seems to suggest that the work was complete.

The physical form of the third volume of the manuscript makes the possibility of missing material rather plausible as well. The printed text contains commentary to every piska’ in Sifre up until piska’ 27 of Parashat Ki Teẓeh.[26] There is no commentary on piska’ot 27-54, but the text resumes with brief comments on piska’54[27] and then ends completely. In the manuscript, piska’ 27 ends at the bottom of a page, which raises the possibility that further commentary followed on subsequent pages which are now lost. The brief comments to piska’ 54 appear on the reverse side of comments labeled as hashmatot; therefore, they may well represent hashmatot to a core commentary, now lost, on the end of Deuteronomy.[28] When one considers the fact that, unlike the first two volumes, the third volume of the manuscript is not bound and does not appear to ever have been bound, the notion that pages from the end of the commentary were lost must be seriously considered.[29]

Conclusions

The conclusion one must draw from the above investigation of the text of‘Emek ha-Netziv is that a historical analysis of the content found in the printed text must be made with caution. The possibility of the text being incomplete must always be considered both in regard to possible editorial censorship and in regard to the possibility that the text originally contained additional chapters that are currently lost. Whereas the core text of the commentary prior to Shelaḥ [30] can be rather definitively dated prior to 1849, the printed text makes no distinction between the core text and later additions. As such, with the exception of a few passages which include embedded historical evidence, no single passage in the printed text can conclusively be dated to the 1830s or 1840s. Nonetheless, there is sufficient evidence, both in Netziv’s own testimony with which this chapter began and in the clues offered by the text and corroborated by the manuscript, to conclude that the bulk of the commentary does indeed reflect a project with which Netziv was engrossed in his early years. Thus, trends which can be identified throughout the printed text and which comprise its general character must indeed be seen as reflective of the intellectual currents of Lithuanian Jewish culture in the 1830s and 1840s.

[1] In recent years, certain circles in the ultra-Orthodox community recommended that Moshe Dombey and N.T. Erline’s adaptation of Barukh Ha-Levi Epstein’s Mekor Barukh, entitled My Uncle the Neẓiv (Brooklyn, N.Y.: Mesorah Publications, 1988), not be read due to its portrayal of Neẓiv as one who did not share all of the values of the contemporary ultra-Orthodox community. See Jacob J. Schacter, “Haskalah, Secular Studies, and the Close of the Yeshiva in Volozhin in 1892,” Torah u-Madda Journal 1 (1989): 76-133; Don Seeman, “The Silence of Rayna Batya: Torah, Suffering, and Rabbi Barukh Epstein’s Wisdom of Women’,” Torah u-Madda Journal 6 (1995-1996): 91-128; Don Seeman and Rebecca Kobrin, “’Like One of the Whole Men’: Learning, Gender and Autobiography in R. Barukh Epstein’s Mekor Barukh,”Nashim 2 (1999): 52-94; Brenda Bacon, “Reflections on the Suffering of Rayna Batya and the Success of the Daughters of Zelophehad,” Nashim 3 (2000): 249-256; Dan Rabinowitz, “Rayna Batya and Other Learned Women: A Reevaluation of Rabbi Barukh Halevi Epstein’s Sources,” Tradition 35: 1 (Summer 2001): 55-69. This position toward Neẓiv, however, was already espoused a century earlier when a series of articles appeared in the Galician newspaper Maḥzike Ha-Da’at (volumes 16, 17, and 18) warning traditionalist Jews to stay away from Netziv’s Bible commentary,Ha‛amek Davar, due to its modern stance toward the authority of the Talmudic Sages. A similar sentiment is reflected in the fact that many ultra-Orthodox houses of study have refused, and continue to refuse, to include Ha‛amek Davar in their libraries.

[2] A value which stands in stark contrast to the overwhelming poverty of most of Geulah’s inhabitants.

[3] See Neil Rosenstein, The Unbroken Chain. (New York: CIS Publishers, 1990) 433-440.

[4] My examination of the manuscript took place in July of 2004 with the assistance of a Summer Travel Grant awarded by the Center for Jewish Studies at Harvard University.

[5] The hashmatot probably represent additions to the text which Neẓiv could not fit in the margins of the page of the core text due to lack of space.

[6] The letters are in cursive form, but Neẓiv generally did not attach his letters to each other. The brown color was probably black when originally applied but has lost its vibrance with the passage of time.

[7] The hagahot seem to have been intended as tangential footnotes to the main commentary in a manner similar to the way in which Netziv’s Harḥev Davar was intended to supplement his Ha‛amek Davar on the Bible. This format was typical of Lithuanian Torah commentary, for reasons which will be explained in Chapter Three below.

[8] I had hoped to demarcate the beginning and end of each addition in my own printed text along with a description of the script used in each addition. The Shapira family, however, was not willing to grant me the sustained access to the manuscript required for such an endeavor.

[9] If it had not been written in order, one would expect to find empty spaces on the bottom of a page where a particular chapter or section ended and new sections beginning on the top of new pages. Instead the end of each section in the manuscript is followed immediately by the beginning of the next section, indicating that they were written sequentially.

[10] There is reason to believe that this manuscript itself is a later recension of an earlier edition. The family showed me what they said were the few extant leaves of an earlier version of the commentary written by Neẓiv which predates the manuscript used for the printed text, but I was not allowed to study them at length. As such, the above analysis does not suggest that Neẓiv actually composed his commentary according to the sequence of the Sifre text, but simply that the transcription of the core text of the commentary into the manuscript at hand was done in sequential order.

[11] See note 14 above.

[12] EH ‘Ekev 4 (III: 52).

[13] See Chapter Two below.

[14] My access to the manuscript was always limited to sitting next to a member of the Shapira family, who would turn to the page I wished to check and look at the specific textual anomaly before deciding whether to let me look as well. In this case I was able to peer over his shoulder and attempt to decipher the acronym. The exact answer this member of the Shapira family gave me was, “Suffice it to say, it is not a siman in Shulḥan Arukh.”

[15] E.g., EH Naso 42 (I: 162); EH Naso 44 (I: 173); EH Matot 1 (II: 279); EHMatot ‛Ekev (III: 45); EH Re’eh 9 (III: 92).

[16] Bet-ayyin-sameh-vav.

[17] EH Shoftim 16 (III: 189).

[18] In cursive Hebrew writing the bet and daled look quite similar.

[19] A glaring example of this type of censorship recently appeared in a photo-offset of the 1926 Frankfurt edition of David Ẓvi Hoffmann’s responsa, Melamed le-Ho‛il, published by the Lebovitz-Kest foundation. In Responsa #56 in the original printing (II: 50), Hoffmann gives his approval, in exigent cases, for an Orthodox Jew to swear before a civil court without a head covering. In the context of his piece, Hoffmann also attests to the fact that Samson Raphael Hirsch instructed the students in the Frankfurt Orthodox school which he founded to cover their heads only for Judaic studies and allowed them to remain bare-headed for their secular studies. The recent photo-offset contains an introduction by a grandson of Hoffmann, David Ẓvi ben Natan Naftali Hoffmann, which gives the reader the impression that the grandson belongs to the ultra-Orthodox community of Jerusalem. Responsa #56, however, permits a practice clearly anathema to that community. Hence, when one turns to page fifty in the off-set, in place of what was earlier Responsa #56, one finds a blank space. I thank Rabbi Moshe Schapiro, librarian at the Mendel Gottesman Library of Yeshiva University, for bringing this example to my attention.

[20] EH Teẓeh (III: 296).

[21] Note that the piska‘ot of Neẓiv do not correspond to those of the Sifre text with which the commentary is printed. In the text of Sifre the last piska’ for which there is continuous commentary is 43, and it then resumes in 54. See Chapter 5.

[22] EH Mas‛ai (II: 334).

[23] EH Ve-’Etḥanan (III: 43).

[24] HrD Num. 6: 19.

[25] Avraham Yizhak Kook, “Rosh Yeshivat Eẓ Ḥayyim,” Kenesset Yisrael, ed. S.J Finn (Warsaw, 1888), 138-147. Also in Ma’amarei HaRe’iyah (Jerusalem, 1984), 123-126.

[26] EH Teẓeh (III: 296). Piska’ot here are according to Netziv’s division. For more on Netziv’s method of dividing piska’ot see Chapter Three below.

[27] EH Teẓeh (III: 299). In the absence of Netziv’s commentary, piska’ot here refer to the division found in the standard Sulzbach edition.

[28] When I asked the Shapira family about the strange ending of work, they too suggested that there might have been more that was lost. When I asked them who had possession of the manuscript prior to them, they declined to give me any names and replied instead, “Suffice it say, it has been handed down, son after son.”

[29] The existence of commentary on the latter parts of Deuteronomy could have been conclusively proven had Neẓiv included a reference to it in his other writings. I have found no such reference, but no conclusions can be drawn from silence.

[30] EH Shelaḥ 1 (II: 10)