Everything I am saying now could change. It is indeed possible that the haredi leadership could do a complete turn-around and decide that it is not helpful to take the country in a direction which while more “pious” would end up destroying it at the same time. But this would take some incredible acts of courage by the haredi leadership. They would have to break with a message that has been advocated for the last thirty years or so.

Here is what R. Shakh wrote about democracy (Mikhtavim u-Ma’amarim, vol. 5, p. 124):

בל נחשוב, שהשיטה הנקראת “דמוקרטיה” היא דבר חיובי . . . האמת היא שהיא אסון לעולם. היא נותנת הרגשה מדומה של “חופש” בו בזמן שלאמיתו של דבר היא רק הפקר, ותו לא . . . הדמוקרטיה היא דבר טרף, וכל כוונתם לעקור דרכה של עם ישראל ולהרסו

ואנו תפילה להרבונו של עולם, אנא פטור אותנו מקללת הדמוקרטיה החדשה שנשלחה לעולם, שהיא ממש כמו מחלת הסרטן שנשלחה לעולם. כי רק התורה הקדושה היא הדמוקרטיה האמיתית.

האדם חייב לחיות בתוך מגבלות, לצורך אושרו וטובתו. ודוקא הדמוקרטיה ההורסת את המגבלות היא המחריבה את האנושות

If anyone still has doubts that the future growth of the haredi parties will present a serious threat to Israeli democracy, here is a passage, from R. Yissachar Meir, that appeared in an official Degel ha-Torah publication, Ve-Zarah ha-Shemesh (Bnei Brak, 1990), p. 630 (emphasis added; many other similar passages could be cited). What will take the place of democracy in the haredi state is spelled out right here:

טעות אחת טעו מנהיגיה הראשונים של המדינה, הם חוקקו חוק הנקרא “דמוקרטיה”. כל אחד יודע דמוקרטיה זו מהי, על פי השיכורים הנמצאים במדינה – שלוש מאות אלף מסוממים חיים במדינה – ועל פי זקנים מסוידים וכו’ נקבע השלטון. כמו כן בכל מיני שוחד, ודרכי כפיה, נקבע ע”י מה שנקרא “בחירות”, איך תנהג המדינה בכל הנושאים העולים על הפרק. על פי דרך התורה, גדולי התורה הם הקובעים את המנהיגות.

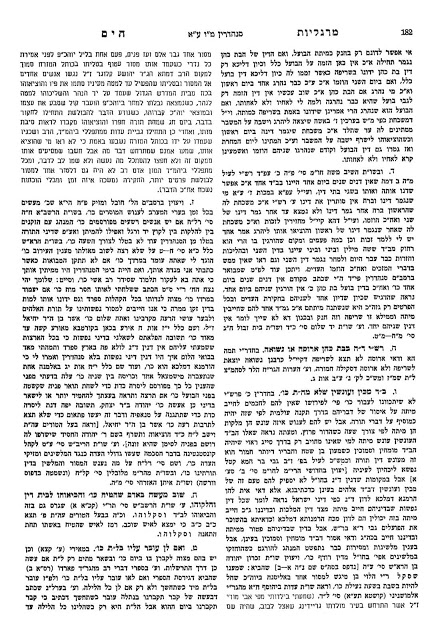

Here is another responsum, by R. Israel David Harfenes, Nishmat Shabbat, vol. 5 no. 500:4.

None of this makes any sense, as people can be under the influence of a secular or anti-religious ideology much like they are under the influence of a Reform or Conservative ideology. If you can apply the logic of tinok she-nishbah to one, there is no coherent reason not to apply it to the other. For good measure, Harfenes also throws in that one who doesn’t believe in the Rambam’s Thirteen Principles is among those who should be killed. Taking a line from the Inquisition, he adds that killing these people is actually good for their souls, not to mention a benefit to the community at large.

In a previous responsum, 400:1, he discusses the same question with regard to the typical secular Jew and concludes likewise that one cannot save them on Shabbat. The only heter he can find is that if the haredi doctors don’t save them, then the secular doctors will refuse to save haredi patients. But unbelievably, rather than seeing this as a natural reaction of the secular Jews upon learning how people like Harfenes don’t value their lives, and are even are prepared to let them die, Harfenes sees this as an example of anti-Orthodox hatred! You can’t make this stuff up.

שאם יתפרסם שרופאים חרדיים אינן מטפלין בשבת עם החולים החילוניים אז הרופאים החילוניים ינקמו נקם ולא ירצו גם הם לטפל להציל חולים מסוכנים מן יהודים חרדיים (כידוע תוקף שנאת הדת הארצינו הקדושה ירחם ה’).

I will call attention to only some of the points Adler puts forth as halakhah. When I read things like this I wonder, how big can the Orthodox tent really be? When are the various communities in Orthodoxy so much at odds with each other that we must speak of two entirely different communities, much like the Protestants are divided into various sects?

One of the main points of the book is to argue that contemporary non-Orthodox Jews are not to be regarded as tinok she-nishbah, and thus they are subject to all the disabilities of brazen Sabbath violators. This means that they do not need to be treated with any respect or dignity. Those who know the relevant halakhot know what I am referring to, but let me cite some examples that you might not have thought of and which are results of his position. These come from chapter 31 and are stated with reference to most contemporary non-religious Jews (since only very few of them qualify as a tinok she-nishbah). How should the non-religious respond when they hear that this is what a rabbi is saying about them:

אין להקדים שלום לאדם רשע . . . אסור לראות פני הרשע . . . ונראה דהוא הדין תנוק שנשבה

אין נוהג בו איסור אונאת דברים . . . נראה דאין כלפיו איסור “לא תחמוד”

פעם ביקר אצל הרבי יהודי חילוני מגולח ובכ”ז הושיט לו הצדיק [ר’ ישראל האגער] את ידו וקבל אותו בסבר פנים יפות, כדרכו בקודש. ישב שם אחד מחסידי צאנז, שהיה מוכר כמתנגד לבית-וויז’ניץ. לחש החסיד באזני הרבי ושאל “מדוע פושט הרבי ידו לפושעי-ישראל זה?” אמר לו הצדיק: “עד שאתה מתפלא עלי, תתפלא על הקב”ה, שגם הוא דרכו בכך, כמו שנאמר ‘אתה נותן יד לפושעים וימינך פשוטה לקבל שבים

On p. 408 Adler writes:

המחלל שבת בפרהסיא (גם אם מחלל לתיאבון) יוצא לענין דינים שונים מכלל “אחיך” עמיתך” “רעך” ומכיון שיצא מכלל עמיתך, אין כלפיו את המצוות הנוהגות “בין אדם לחבירו” וכן אין נוהגים כלפיו את האיסורים, כגון הכלמה ולשון הרע.

Is there anyone in the kiruv world who believes this? Would anyone ever become religious if he even had an inkling that there are rabbis who advocate this position about the future baal teshuvah’s parents?

[8] Aren’t the many haredi hesed organizations that don’t distinguish between Jews’ levels of religiosity a good sign that the mainstream haredi world rejects the viewpoints of Adler and Sternbuch?

On p. 470 he says that it is forbidden to belong to an organization that has non-Orthodox members, and this even includes charitable organization. The reason given for this position is as follows:

כיון שהישיבה עמהם גורמת קירור בעבודת השי”ת, ומלבד זאת, אופן החשיבה וקבלת ההחלטות אינם לפי דעת תורה.

So we see that it is problematic for an Orthodox Jew to have any dealings with the non-Orthodox. Although the author cites R. Samson Raphael Hirsch to justify this extreme position, this is a complete distortion. Hirsch opposed membership in organizations that were led by the non-Orthodox or even had organizational ties with non-Orthodox groups. He never said that individual non-Orthodox Jews would not be welcome to join with the Orthodox for the betterment of the Jewish community.

On p. 406 Adler tells us that one cannot sell or rent an apartment in a religious neighborhood to a non-religious person. Will the author then complain when the non-religious don’t want to sell or rent to haredim (especially if they think that these haredim might hold the same views as Adler)? If it is OK for haredim not to want to live together with secular Jews because of the “atmosphere” the latter bring, why have the haredi Knesset members cried racism when secular residents don’t want an influx of haredim for exactly the same reason? In a democracy one can’t have it both ways.

[9]

Adler is part of a growing trend in haredi writings not to see the secularists as tinok she-nishbah, with all the halakhic implications this entails. While Adler acknowledges the existence of tinok she-nishbah as a category, note what he puts in brackets which pretty much empties the category of any meaning (p. 31):

ולענין הלכה, מכיון שאין בנו כח להכריע, במחלוקות אלו, וגם אין כל הענינים שוים, מתי נקרא בשם “תנוק שנשבה” ומתי לא, ובפרט קשה ההכרעה המציאותית של “שיעור ידיעת כל אחד ואחד” בזמנינו, לכן, בכל הנוגע לדיני תורה, יש להחמיר ולנהוג כלפי מחלל שבת בפרהסיא [שלא ידוע ככופר] ככל דיני “אחיך”, כגון לענין דיני גמילות חסד, לבקרו בחוליו, לתת לו צדקה, להלוות לו, להשיא לו עצה טובה. וכן יש להצילו ולהחיותו.

But when it comes to Shabbat, Adler states that it is absolutely forbidden to violate the Sabbath to save a non-religious person, even if he is a tinok she-nishbah! (p. 556).

I realize that, with only some exceptions, Adler hasn’t made up any of the material in his book, and even the most extreme rulings can be found in earlier traditional sources. So what does it say about so much of contemporary Orthodoxy, be it haredi, Habad, or Modern Orthodox, that its adherents would never dream of relating to the non-Orthodox the way Adler prescribes?

[10] The reason they wouldn’t dream of relating to the non-Orthodox this way is not because they can point to other halakhic sources that disagree with the ones Adler cites (although the scholars among them can indeed point to these sources). There is something much more basic at work, namely, the moral intuition of people which even when it comes into conflict with what appears in halakhic texts does not agree to simply be pushed aside. Most Orthodox Jews of all stripes refuse to believe that what Adler is advocating is what God wants. It is impossible for them to accept that the Judaism they know and cherish, which has been taught to them by great figures, would have such a negative outlook, and all the halakhic texts in the world won’t be able to change their minds.

Since we are dealing with Adler, let me also note that he gives us advice on how to create anti-Semitism in the world and reinforce the stereotype of the “cheap Jew” (p. 415):

אין לתת לגוי מתנת חינם [כגון “טיפ” (-תוספת) הנהוג לשלם למלצר או נהג מונית]

On p. 417 he writes (emphasis added):

אין איסור לייעץ לגוי עצה שאינה הוגנת ולא זו בלבד אלא שאסור להשיא לו עצה הוגנת

As the source for the underlined halakhah he cites

Sefer ha-Hinukh no. 232. To begin with, there is the methodological problem of recording something as halakhah because it is found in the

Sefer ha-Hinukh when it is not found in the

Shulhan Arukh or any of the classic responsa volumes. This is what I call cherry picking halakhot, and is quite common today. People write books on the most arcane topics and in order to fill the pages they cite opinions from any book ever written, and record all the opinions they find as if they are halakhah. In this case, however, the halakhah cited here does not explicitly appear in the

Sefer ha-Hinukh. All the

Sefer ha-Hinukh states is that there is a biblical prohibition to give bad advice to a fellow Jew. But who says that this means that it is permitted when dealing with a non-Jew? It could still be forbidden for a variety of other reasons (perhaps even rabbinic), just not from this particular verse. Even if the

Sefer ha-Hinukh does mean what Adler says (and the

Minhat Hinukh also assumes that this is the meaning), only in the note does Adler reveal that the

Minhat Hinukh explicitly holds an opposing position. This is the general trend in the book. He puts extreme positions in the text itself, which are on some occasions based on his own understanding, while only in the notes does he reveal the authorities who disagree.

(R. Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg defends the Minhat Hinnukh‘s position in his Mishmeret Hayyim, vol. 1, pp. 125-126. But it still makes for uncomfortable reading as he writes:

כיון דבעלות דגוי אינו חשוב כל-כך אין לאו דגזל שייך גבי גוי, וכן באיסור רציחה דהאיסור הוא דנוטל נשמתו וגבי גוי דלא חשוב נשמתו כל-כך לא שייך לאו זה

It would be pretty hard to be an

Or la-Goyim while at the same time following Adler’s prescriptions. In a previous post I already mentioned that there is no Modern Orthodox synagogue in the country that would hire someone who had his perspective, and this shows a real cultural divide between at least some haredim and the Modern Orthodox. (I say “some haredim” because I believe that in this matter many, and perhaps most, haredim share the Modern Orthodox perspective.)

[11]

At the end of the section in which Adler records what I quoted from him about tipping waiters or cab drivers, he adds:

מפני דרכי שלום מותר

I would like someone to explain to me how it could ever

not be

darkhei shalom?

[12] Adler is speaking to people who wear black suits and hats, the sort that everyone recognizes as Jewish. So by definition if you stiff the cab driver or the waiter it is an immediate

hillul ha-shem? Therefore, what sense does it make to even quote the halakhah mentioned above? Isn’t it irresponsible to allow yeshiva students on their own to determine when their actions will cause a

hillul ha-shem and when not?

Since this post has dealt with how to relate to the non-religious and non-Jews, let me now turn once again to something relevant in Artscroll. Originally I thought that the example I will now point to was an intentional falsehood, because the Hebrew Artscroll gets it right. However, based upon the note to the passage that we will see, I am now no longer sure. It is one thing to translate a censored passage in the name of good relations, but it is hard to imagine that people who know the truth would go so far as to insert a false note. As thousands of people doing daf yomi have been misled as to the meaning of the talmudic passage we will see, if the distortion is intentional this would seem to be a classic case of ziyuf ha-Torah. When authors added a note at the beginning of their books stating that all references to non-Jews referred to those pagans in China and India, everyone knew it wasn’t to be taken seriously, so there was no ziyuf ha-Torah. Yet people who reads the Artscroll translation and note assume that they are getting the Torah truth. As such, I am more inclined to think that what we will now see is a simple error, rather than a “tactical” mistake.

Avodah Zarah 26a-b reads:

העובדי כוכבים ורועי בהמה דקה לא מעלין ולא מורידין אבל המינין והמסורות והמומרים היו מורידין ולא מעלין

Artscroll translates: “Idol worshipers and shepherds of small animals, the law is that we neither raise them up from a pit nor lower them into a pit. But as for the minin, the informers and the renegades, they would lower them into pits and not raise them up.”

This is, indeed, a proper translation of what appears in the Talmud. Yet in every edition of the Talmud before the Vilna Shas of 1883 the text states אבל המינין והמסורות והמומרים מורידין ולא מעלין . That is, the word היו, which makes the passage past tense (and thus no longer relevant), is not authentic but was added to avoid problems with the censor. The Oz ve-Hadar edition of the Talmud points out that the word היו was only recently added. Soncino and Steinsaltz also recognize this. What is particularly noteworthy is that the Hebrew Artscroll also knows this, and tells the reader that the word היו is not authentic.

In its note on the passage in both the Hebrew and English editions, Artscroll quotes the Hazon Ish, Yoreh Deah 2:16, that the type of actions referred to in the Talmud are no longer applicable. Why then didn’t Artscroll mention in the English edition that the word היו is not authentic? Furthermore, Artscroll’s citation of the Hazon Ish is mistaken, although as mentioned, I am not sure whether it is an intentional falsification. Contrary to what Artscroll states, the Hazon Ish’s comment was only made with reference to heretics. His “liberal” judgment was never stated with regard to informers.

In its note, Artscroll states: “It goes without saying that the law never applied in places where government regulations would prohibit such an act.” Once again, I am not sure whether Artscroll really believes that this is true. As a historical statement it is false. Here is a page from R. Reuven Margaliyot’s

Margaliyot ha-Yam, vol 1, p. 91b (to

Sanhedrin 46a), that shows how even in the not-so-distant past an informer could be killed.

2. In this post I mentioned the outrageous accusation, based on nothing at all, that the telegram from Kobe was actually sent by the Chief Rabbinate in order to be able to pressure other rabbis to accept the Chief Rabbinate’s position on the dateline issue. Dr. Dov Zakheim sent me the following valuable email:

I noted in your recent blog you point out that some chareidim are asserting there was never a telegram from Kobe. There was. My father zt”l sent it. He had been the legal counsel of the Jewish community of Vilna (as well as a musmach of Ramailes) and also Reb Chaim Ozer ztl’s personal assistant and legal advisor (see his introduction to his sefer Zvi ha-Sanhedrin). He escaped from Vilna in 1941 and managed the Mirer Yeshiva’s legal affairs (where my uncle zt”l was a talmid) when they left Vilna, on the trans-Siberian, in Kobe and then in Shanghai.

Also in the post I referred to the letter published by R. Kasher in which lots of great rabbis refer to the State of Israel as the beginning of the redemption. I noted how Zvi Weinman has shown that this is a religious Zionist forgery, as at least some of the rabbis never signed such a letter. I mentioned that we don’t know if Kasher was responsible for the forgery (as Weinman appears to think) or someone else. Sholom Licht was kind enough to call my attention to

this source from where we see that the letter Kasher published already appeared in

Ha-Tzofeh many years prior, so Kasher clearly had nothing to do with the forgery.

3. In the last few posts I have dealt with Artscroll a good deal, as is only proper since Artscroll is the most significant Jewish publishing phenomenon of our time. I still have a lot more to say, but let me now turn to R. Jonathan Sacks’ siddur, and give an example where Sacks gets it wrong while Artscroll gets it right.

The blessing to be recited upon lightning and Birkat ha-Hamah is עושה מעשה בראשית This goes back to Mishnah Berakhot 9:2. Although the standard version of the Mishnah omits the word מעשה, it is recorded in various medieval texts and this is how the blessing has come down to us.

What does עושה מעשה בראשית mean? The first thing we must do is figure out if there is a

segol or a

tzeirei under the

shin in עושה. Looking at the siddurim in my house that have English translations, I found that Sacks, Birnbaum, Sim Shalom, and Artscroll, have a

segol.

[13] This is also what appears in the Kaufmann Mishnah. See

here. However, the Metsudah siddur and the Blackman Mishnayot have a

tzeirei.

What is the difference between the vocalizations? If there is a segol than the words עושה מעשה בראשית should be translated in the English present, as עושה is a verb. If there is a tzeirei then עושה is a noun, as in the words of Hallel (from Ps.115:15): עושה שמים וארץ, which means “Maker of heaven and earth.” Let us see if the translations follow this rule. Artscroll, which has a segol, translates: “Who makes the work of Creation.” This translation is correct, although I don’t know why the C in creation is capitalized. This translation implies the continuing work of creation, as reflected in the words of the prayer: המחדש בטובו בכל יום תמיד מעשה בראשית

Birnbaum translates עושה מעשה בראשית as: “Who didst create the universe.” This is incorrect, as the passage is not in the past tense. Sacks, who also has a segol, translates: “Author of creation.” This too is incorrect, as עושה with a segol is a verb, not a noun. Sim Shalom, also with a segol, translates: “Source of Creation.” This too is incorrect.

Now for the texts that have a

tzeirei: Blackman translates: “the author of the work of the creation”, which is a correct rendering. Metsudah, on the other hand, translates: “Who makes the work of Creation.” Leaving aside the capital “C”, this is a mistaken translation. While Metsudah has עושה with a

tzeirei under the

shin, it translates as if there was a

segol.

[14]

Artscroll, while being correct when it comes to this blessing, does not get a pass when it comes to the word עושה. In the Artscroll siddur, pesukei de-zimra, p. 70, we find the words עושה שמים וארץ. This comes from Psalm 146:6. There is a segol under the shin which means that it is a participle and should be translated here with the English present tense, as are all the other verbs in this Psalm. Yet Artscroll translates עושה שמים וארץ as “Maker of heaven and earth”, which is incorrect. Sacks follows many other translations by rendering the words: “who made heaven and earth”. Yet this too is not correct and doesn’t follow the model of the Psalm, which has a series of participles that are to be translated as the present tense:

עושה שמים וארץ

השומר אמת לעולם

עושה משפט לעשוקים

נותן לחם לרעבים

מתיר אסורים

פוקח עורים

זוקף כפופים

אוהב צדיקים

שומר את הגרים

What about the word בונה in the blessing בונה ירושלים? There is a tzeirei under the nun in בונה which means that it is not a verb. Artscroll correctly translates the phrase as “Builder of Jerusalem”. Birnbaum and Metsudah also get it right. However Sacks (and also De Sola Pool and Sim Shalom) are mistaken in their translation. Sacks renders בונה ירושלים as if the nun had a segol: “Who builds Jerusalem.”

Since בונה ישראל must be translated as “Builder of Jerusalem”, and all translations are in agreement that גואל ישראל means “Redeemer of Israel”, does this mean that the conclusion of all the blessings of the Amidah should follow this model? What about חונן הדעת? Artscroll translates : “Giver of wisdom”, seeing חונן as a noun. Birnbaum and Metsudah do likewise. However, Sacks assumes חונן is a verb and translates: “who graciously grants knowledge.” This rendering (which I thinnk is in error) is also found in De Sola Pool and Sim Shalom.

How about מחיה המתים? Is the word מחיה a verb? Artscroll assumes yes and translates: “Who resuscitates the dead.” Sacks agrees with this, but Metsudah, striving for consistency, translates: “Resurrector of the dead.” Metsudah is, in fact, the only siddur that as a rule translates the concluding blessings of the Amidah along this model, while the other translations alternate between verb and noun. Here are some of Metsudah’s translations:

רופא חולי עמו ישראל – Healer of the sick of His people Israel

מברך השנים – Blesser of the years

מקבץ נדחי עמו ישראל – Gatherer of the dispersed of His people Israel

שובר אויבים ומכניע זדים – Crusher of enemies and subduer of the insolent

Although Metsudah follows this rule, for every rule there are exceptions, and even Metsudah translates שומע תפלה as “Who hears prayers”. Yet perhaps this is not an exception, and even here Metsudah intended “The hearer of prayers”, but since this doesn’t sound so good in English they came up with a more felicitous wording. It is true that the underlined words of the blessings המחזיר שכינתו לציון and המברך את עמו ישראל בשלום have to be seen as verbs, and Metsudah translates them as such. But I think that these are a different type of blessings than the ones in the middle of the Amidah.

The question to be asked is must we assume that there is a consistency of form in a prayer like the Amidah? If the answer is yes, then Metsudah is the only translation to get it right, and they must be recognized as having picked up on something that eluded all their predecessors and successors.

Finally, let me return to the blessing מחיה המתים. I asked if the word מחיה is a verb, and noted that Artscroll and Sacks indeed translated it this way. However, they are both incorrect for the simple reason that in their siddurim there is a

tzeirei under the

yud of

מחיה. There are siddurim, such as Tehilat ha-Shem, that have a

segol under the

yud. In such a case, the word should be translated as a verb. However, when there is a

tzeirei it must be translated as a noun. Metsudah once again gets it right, translating “Resurrector of the dead.”

[15] Right before this, we find the words מלך ממית

ומחיה. Here there is a

segol under the

yud, meaning that it is a verb and is to be translated as “Who causes death and restores life”.

Artscroll and Sacks also err in their translation of מחיה מתים במאמרו in Magen Avot in the Friday night service. There is a tzeirei under the yud meaning that it must be translated as “Resurrector of the dead with His utterance.” Artscroll mistakenly renders: “Who resuscitates the dead with His utterance,” using the same translation from the Amidah for the words מחיה המתים.

I can’t figure out Sacks’ method here. In the Amidah he translates מחיה מתים as: “who revives the dead”, but in

Magen Avot he translates: “By his promise,

He will revive the dead.” This is incorrect, as it turns the sentence into the future tense, which it is not. Furthermore, if it was to be translated as such, why not do so in the Amidah as well, as the words are identical? Indeed,

Magen Avot is nothing but an abridged version of the Amidah, so by definition the translation must be the same.

[16] Translating במאמרו as “By His promise”, which I assume means “in accordance with His promise,”

[17] is also incorrect, as the passage refers to God’s word, or better yet, the power of God’s word, not any promise.

[18]

3. I want to briefly call attention to three books that have recently appeared and which I hope to discuss in future posts. The first is Gil Perl’s

The Pillar of Volozhin: Rabbi Naftali Zvi Judah Berlin and the World of 19th Century Lithuanian Torah Scholarship. The second is Eugene Korn and Alon Goshen-Gottstein, ed.,

Jewish Theology and World Religions. The third is Ben Zion Katz,

A Journey Through Torah: A Critique of the Documentary Hypothesis. I know that there are many Seforim Blog readers who will find these books worth reading.

4. Those who want to post (or read) comments, please access the Seforim Blog site by going to http://seforim.blogspot.com/ncr Only by doing this will you be taken to the main site (and not have a country code in the URL). We have recently learnt that readers outside the United States do not have access to the comments posted and in the U.S. We don’t know why this is, or how to fix it, but the above instruction fixes the matter.

Indeed, there is a sort of reciprocal dependence between democracy and justice that impels everyone to work responsibly to safeguard each person’s rights, especially those of the weak and marginalized. This being said, it should not be forgotten that the search for truth is at the same time the condition for the possibility of a real and not only apparent democracy: “As history demonstrates, a democracy without values easily turns into open or thinly disguised totalitarianism” (

Centesimus Annus, n. 46).