A review of Marc Michael Epstein’s The Medieval Haggadah, Narrative & Religious Imagination

Marc Michael Epstein, The Medieval Haggadah, Art, Narrative & Religious Imagination, Yale University Press, New Haven & London: 2011, 12, 324 pp. Most discussions regarding the Haggadah begin with the tired canard that the Haggadah is one of the most popular books in Jewish literature, if not the most popular, and has been treasured as such throughout the centuries. Over sixty years ago, Isaac Rivkin noted that as a matter of fact, only since the 19th century has the Haggadah become one of the most printed Jewish books. Prior to the 19th century, the Haggadah is neither the most printed nor most written about work in the Jewish cannon.[1] Epstein does not fall prey to this canard nor any other of the many associated with the Haggadah. Dr. Epstein’s survey of four Jewish medieval manuscripts is novel, vibrant, and sheds new light on these manuscripts, as well as Jewish manuscripts and the Haggadah generally. Epstein covers four well-known medieval Haggadah manuscripts:[2] The Birds’ Head Haggadah, The Golden Haggadah,[3] The Rylands Haggadah,[4] and the Brother to the Rylands Haggadah. First, a word about manuscript titles. Sometimes manuscripts are referred to by the city or institution that houses or housed the manuscript, while in other instances, especially when a manuscript contains a unique marking or the like, that unique identifier may be used to describe the manuscript. The Rylands Haggadah (currently housed at the John Rylands Museum, Manchester, UK), is an example of the former, and the Birds’ Head Haggadah is an example of the latter. In the case of the Birds’ Head, most of the figures depicted in the manuscript are drawn not with human heads, but with birds’ heads. Similarly, the Golden Haggadah is another example which gets its title due to the proliferation of gold borders and filler. Finally, the Brother to the Rylands, gets its title from the similarly of its illustrations to that of the Rylands, indicating some connection or modeling between the two manuscripts. As alluded to above, Epstein is not the first to discuss these manuscripts. Indeed, in the case of both the Birds’ Head and the Golden Haggadah, book length surveys have already been published.[5] Epstein, however, differs with his predecessors both in terms of his method as well as what he is willing to assume. Regarding assumptions, previously, many would take the path of least resistance in explaining difficult images and attribute confusing or complex illustrations to errors or lack of precision of the illustrator. Rather than assume error, Epstein gives the illustrations and illustrators their due and, in so far as possible assumes that the images are “both coherent and intentional.” As an extension of his “humility in the face of iconography,” Epstein attempts “to understand how the authors understood it rather than assume that [he] must know better than they did.” He does “not fault the authorship for what” he, “as a twenty-first century viewer, might fail to notice or understand concerning the structure or details of the iconography.” Furthermore, engaging with illustrations not only from tracing the history of how the image came into being but, more importantly, how that image was interpreted and what meaning it carried for its audience throughout its transmission is also one of Epstein’s goals. In furtherance of these goals, Epstein is all too aware of his own limitations and throughout the book, Epstein willingly admits both where the evidence can lead and, what is pure speculation. All of this translates into a highly satisfying and illuminating (no pun intended) perspective on these and Jewish manuscripts in general. The book is divided among the four manuscripts, with each getting its own section, with the exception of the Rylands and its Brother that are included in a single section. At the beginning of each section, all of the relevant pages from the manuscript are reproduced. The reproductions are excellent. This is not always the case in other books that reproduce these images. Indeed, in Narkiss, et al. who compiled an Index of Jewish Art that includes detailed discussions regarding a variety of medieval Haggadah manuscripts, only reproduce the images in black and white.[6] Similarly, Metzger, in her La Haggada Enluminée, also only reproduces the images in black and white (and many times the images are of poor quality). Here, each page containing an image is reproduced in full, in a high quality format that allows the reader to fully appreciate the image under discussion. Appreciating that to obtain similar high quality images requires the purchase of an authorized facsimile edition, which in some instances can be cost prohibitive highlights the importance and attention to detail that characterizes Epstein’s work on the whole. The Birds’ Head Haggadah is the oldest illustrated Haggadah text, dated to around the early 1300s. This manuscript is not the only Jewish manuscript to use zoophilic (the combination of man and beast) images. Zoophilic images can be found in a variety of contexts in Jewish manuscripts. For example, in the manuscript known as Tripartite Machzor, men are drawn normally while the women are drawn with animal heads.[7] Or, the well-known manuscript illustrator Joel ben Simon playfully illustrates the prayer God should save both man and beast, which can be read as God should save the man/beast, with a half human-half beast: When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope. Epstein ably summarizes the positions and based upon a close examination of the illustrations as well as his stated methodology, dismisses much of the prior theories. His ultimate conclusion, which builds upon the halachik position, is more nuanced and, hence, more believable, than his predecessors. The Birds’ Head provides a striking example where Epstein’s unwillingness to simply ignore complexity by claiming error, demonstrates the interpretative rewards offered to a close reader of the illustrations. While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. The inclusion of these persons, and allowing them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head, may be a statement regarding sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity. Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.

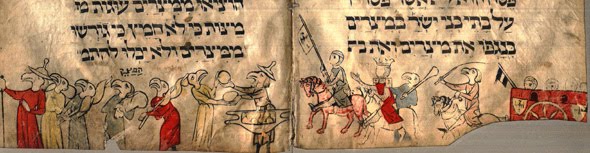

When it comes to the Birds’ Head manuscript, a variety of reasons have been offered for its imagery, running the gamut from halachik concerns to the rather incredible notion that the images are actually anti-Semitic with a bird’s beak standing in for the Jewish nose trope. Epstein ably summarizes the positions and based upon a close examination of the illustrations as well as his stated methodology, dismisses much of the prior theories. His ultimate conclusion, which builds upon the halachik position, is more nuanced and, hence, more believable, than his predecessors. The Birds’ Head provides a striking example where Epstein’s unwillingness to simply ignore complexity by claiming error, demonstrates the interpretative rewards offered to a close reader of the illustrations. While most of the images carry a bird’s head, there are a few exceptions. Most notably, non-Jews, both corporal and spiritual do not. Instead, non-Jewish humans as well as angels have blank circles instead of faces. But, there is one scene that poses a problem. One illustration shows the Jews fleeing Egypt (all with birds’ heads), being pursued by Pharaoh and his army. But, unlike the rest of the figures in Pharaoh’s army, two figures appear with birds’ heads. Some write this off to carelessness on the illustrator’s part. Epstein, who credits his (then) ten-year old son for a novel explanation, offers that these two figures are Datan and Aviram, two prominent members of the erev rav, those Jews who elected to remain behind. The inclusion of these persons, and allowing them to remain with their “Jewish” bird’s head, may be a statement regarding sin, and specifically, the Jewish view that even when a Jew sins, they still retain their Jewish identity. Sin, and including sinners as Jews, are motifs that are highlighted on Pesach with the mention of the wicked son and perhaps is also indicated with this illustration. The illustrator could have left Datan and Aviram out entirely or decided to mark them some other way rather than the Birds’ head. Thus, utilizing this explanation allows for the illustrator to enable a broader discussion about not only the exodus and the Egyptian army’s chase, but expands the discussion to sin, repentance, Jewish identity, inclusiveness and exclusiveness and other related themes.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

Epstein’s discussions of the other manuscripts are similarly eye-opening. For instance, the Golden Haggadah is an example of the Sefard manuscript Haggadah genre. Manuscript haggadahs are placed in two broad categories, Ashkenaz and Sefard. The former’s illustrations appear in the margins and generally explain the text or refer to Pesach scenes such as baking matzo or looking for hametz. The latter’s illustrations appear before the text and are a series of illustrations, appearing either in two or four panels on a single page, depicting the beginning of Jewish history with Adam and Eve, or in the case of the Sarajevo haggadah, the actual creation sequence. The illustrations culminate with the exodus. But, unlike the Ashkenaz examples, the Sefard manuscripts generally do not illustrate the Haggadah text (with the exception of HaLachmanya, a picture of matzo or the like). The Golden Haggadah follows the Sefard conventions and includes the Jewish history scenes. Epstein demonstrates, however, that the images should not just be read chronologically. Rather, the Golden Haggadah illustrator subtly linked events that did not necessarily follow in time. For example, the placement of the water in a scene depicting Jacob’s blessing to Pharaoh is linked to the scene, occurring much later, to the boys being thrown in the Nile and is similarly linked by imagery to Moses being saved from the Nile, as well as Moses rescuing Jethro’s daughters. Epstein connects all of these scenes by noting the unique method and placement of the water in the scenes. But the linkage is not merely water, instead, this interpretation affords insight into God’s blessings, promises, the parameters and methods of His divine punishment of “measure for measure,” gratitude, and salvation. Again, this is but one example where close examination of the illustrations enriches the Haggadah discussion. All of Epstein’s discussions display his keen awareness and erudition regarding illustrations appearing in both the manuscript as well as print Haggadahs. Although the work employs end notes, which we find generally to indicate that the notes are unnecessary for the text, the notes should not be ignored. They are full of interesting sidebars as well as additional information on the illustrations discussed and the history of Haggadah illustration.[8] As a testament to the importance of this work, as well as its accessibility, the book was originally published after Pesach last year (hence our belated review) and, already, before even a single Pesach, its publisher is sold out. The work has already received numerous accolades from numerous others to which we add our small voice. This is an incredible work in terms of its insights, methods, and production values that is a welcome breath of fresh air to stale and repetitive Haggadah genre.

[3] The link for viewing the Golden Haggadah at the bottom of page here or in a fully sizable and zoomable image here.

[4] The Rylands Haggadah is currently on display at the Met in NYC until September 30, 2012.