Answers to Quiz Questions and Other Comments, part 2

Answers to Quiz Questions and Other Comments, part 2

by Marc B. Shapiro

1. In my previous post, in discussing the words in Ecclesiastes 2:8 עשיתי לי שרים ושרות, I referred to the interpretation in Kohelet Rabbati. This very section of Kohelet Rabbati has an amazing comment, which as far as I know was never referred to in the dispute over Sara Hurwitz’ rabbinical ordination. Commenting on the words שדה ושדות, which appear in the same sentence as שרים ושרות, the Midrash states:

שדה ושדות: דיינים זכרים ודיינות נקבות

In other words, Solomon is portrayed as appointing female dayanim! (See also Ruth Rabbah 1:1 where Deborah and Yael are described as judges.[1]) The standard commentaries find this passage very difficult and offer alternative explanations, sometimes in opposition to the plain sense of the words. Etz Yosef suggests that the job of the women was to judge other women. R. David Luria adopts the lav davka approach, and assumes that דיינות must mean policewomen of sorts.

ודיינות נקבות: לאו דווקא דיינות דאשה פסולה לדון. אלא שופטת להשגיח שלא ישלטו [ישלחו?] הנשים בעולתה איש לרעותה את ידה

His position is rejected by R. Abraham Horowitz, Kinyan Torah ba-Halakhah, vol 1, no. 8:3. Rabbi Horowitz, who was a member of the Edah Haredit beit din, assumed that when the Midrash referred to female dayanim, it didn’t mean that they actually took part in beit din proceedings, but it did mean that they decided halakhic matters, and in that sense they are דיינות. Here are his words, which everyone should examine closely.

ובאמת ל”י [לא ידעתי] מה החרדה הזאת דהא הפת”ש בחו”מ סי’ ז’ סק”ה הביא מספר החינוך מצוה קנ”ח דאשה חכמה ראוי’ להורות . . . אפש”ל דיינות שנתמנו [ע”י שלמה] רק לפסוק הוראה ולא לדון. ועימנ”ח סו”מ ע”ח דפשיטא לי’ דנשים מצטרפות לרוב חכמי הדור אם חולקין באיזו דין . . . מכ”ז נראה דאין לזלזל בסמכות אשה כשירה

I requested that readers examine his words, because in the backlash over Hurwitz’ ordination a number of statements were made the upshot of which was that halakhic decision-making is reserved for men. Ironically, this position is given support by at least some of the women serving as yoatzot, for they are careful to stress that while they provide guidance, they don’t, Heaven forbid, actually decide halakhah. When there is a real halakhic question they turn to the experts, that is, the male rabbis. The message of this is, of course, that women, no matter how learned, are disqualified from deciding halakhah.[2]

Returning to Kohelet Rabbati, R. Yisrael Be’eri accepts that the Midrash means what it says when it refers to dayanim, but suggests that Solomon not only had female courts, but also “co-ed” batei din. See Ha-Midrash ka-Halakhah (Nes Tziyonah, 1960), p. 317:

ולולי מסתפינא אמינא שזה היה הרכב זוגי ז”א אותו דין היה מתברר בפני בי”ד רגיל וכן הוסיף שיתברר בפני דיינות נקבות שאולי יש בהן בינה יתירה וגישה מיוחדת ואחר כך שוקלין זה מול זה ואז היה מתברר הדין בדקדוק ושיקול מיוחד וצ”ע.

It is noteworthy that he sees value in having the female dayanim examine the matter, since they can bring a feminine perspective to bear. If I just presented the text without telling you who the author was and when it was written, I am sure people would assume that only a modern feminist type could have penned these words. Yet we see that this is not the case.

R. Hayyim David Halevi also deals with this Midrash (Aseh Lekha Rav, vol. 8, pp. 247-248). He suggests that the Midrash is indeed operating under the assumption that there is no problem with women dayanim. Alternatively, he suggests that Solomon and his council accepted the authority of the women, and therefore this was permissible. In other words, there is only a halakhic problem when a woman is made a dayan against the will of the community, but if she is accepted by them, then she can serve. And how do we determine if the community accepts her as a dayan? Halevi explains:

וקבלה ודאי שמועילה, והכל כשרים לדון בקבלה, וקבלת גדולי הקהל מספיקה ואין צורך שכל העומדים לדין יקבלו עליהם. וכן מצאנו “דיינות נקבות” כלשון המדרש, ואין סתירה להלכה

What this means is that if the leaders of the community accept women dayanim, then this is sufficient. (I am speaking about in matters of Hoshen Mishpat, not dayanim for Even ha-Ezer.) Therefore, if leaders of the OU or the RCA declare that they accept women, that would open the door to appointing a woman as a dayan on the RCA beit din. Halevi refers to acceptance by גדולי הקהל. In the context of the United States, where there are lots of different kehilot, I would assume that this means that if the leaders of any one community, or even of one synagogue, agree to accept a woman as dayan, then this is sufficient.

R. Ben Zion Uziel also claimed that women can serve as dayanim, and the means of achieving this would be through a takanah. He cites meta-halakhic reasons to explain why this is not a good idea, but from a pure halakhic standpoint, he sees it as entirely acceptable.[3]

Leaving aside the issue of serving as a dayan, it is obvious to me that women rabbis are coming to Modern Orthodoxy, even if the powers that be are standing firmly against it. Yet they have already let the genie out of the bottle. By sanctioning advanced Torah study for women, there is no question that the time will come when there will be women scholars of halakhah who are able to decide issues of Jewish law. The notion that a woman who has the knowledge can “poskin” is not really controversial, and has been acknowledged by many haredi writers as well.[4] Very few rabbis are poskim, but every posek is by definition a “rabbi”, whether he, or she, has received ordination or not.[5] So when we have women who are answering difficult questions of Jewish law, they will be “rabbis”,[6] and no declarations by the RCA or the Agudah will be able to change matters. I am not talking about pulpit rabbis, as this position has its own dynamic and for practical reasons may indeed not be suitable for a woman. Yet as we all know, very few rabbis function in a pulpit setting, and much fewer will ever serve as a dayan on a beit din.

The reason why the issue of ordaining women has been so problematic is because the Orthodox community is simply not ready for it. Yet when women will achieve the level of scholarship that I refer to, and are already deciding matters of halakhah, then their “ordination” will not be regarded as at all controversial in the Modern Orthodox world, and will be seen as a natural progression. People will respond to this no differently than how they responded to the creation of advanced Torah institutes for women. [7] Since women were already being taught Talmud, the creation of these institutes was a natural step.

There is one more thing that needs to be added, and that is that we have not reached the point where there are women halakhic authorities.[8] I hope I won’t be accused of bashing women by pointing out the following fact, that as of 2012 not one traditional sefer, in Hebrew, written by a woman has been published. By traditional sefer I mean a halakhic work or a commentary on a talmudic tractate. I am waiting for this day, which I hope won’t be too long in the future. I also hope that a learned woman is currently working on a commentary to a tractate, even if it is one of the easier tractates such as Megillah. The point is that for women to be recognized as talmudic and halakhic authorities they will have to do exactly what the men do, and that is show the world that they are serious talmidot hakhamim. The major way to do this is through publishing. (Publishing has its own significance, even if no one actually reads the book. Let’s be honest, of the many volumes of commentary on talmudic tractates that are published by people in yeshiva and kollel every year, does anyone read them? With so many great works of rishonim and aharonim on the tractates, as well as the writings of contemporary gedolim, the modern commentaries by unknown talmidei hakhamim are understandably not anyone’s focus. Yet they are of great benefit to the author, in developing his ideas and advancing his learning, and that is reason enough for the works to appear.)

I agree that it isn’t “fair” that while men can be given the title “rabbi” simply by learning sections of Yoreh Deah, the women must do a lot more to be accepted. But that is required any time new developments come into place. I have been assured by people in the know that the day is coming when we will have first-rate women halakhists and talmudists. It will be fascinating to see what insights they bring to matters, and if a woman’s perspective affects how halakhah is decided. But we haven’t reached that day yet, and just as importantly, the Orthodox world as a whole is not yet ready for that day, as they have not yet become comfortable with the idea of a woman poseket.

In note 7 I refer to the recent article by Broyde and Brody in Hakirah 11. While they leave open the possibility of a future with women rabbis, R. Hershel Schachter also has a very short article in that issue, and he is completely opposed. What I think is interesting is that the only recent authority he cites in support of his rejection of women rabbis is “Rabbi Shaul Lieberman.” I guess R. Schachter regards Lieberman as one of the gedolei Yisrael.[9]

Regarding R. Schachter’s opposition to women rabbis, there is one other point worth noting. In an earlier post, available here, I wrote as follows:

R. Hayyim Joseph David Azulai has an entry for “rabbanit” in his Shem ha-Gedolim. He lists there a few learned women. When Azulai uses the term rabbanit, it does not mean “rebbetzin” but “female rabbi”. I am sure that there are those who would object to the Hida that these women were never “ordained”. Yet the Hida also includes many others who were not ordained, but I don’t think anyone would take the title of “rabbi” away from them. One such figure is Moses ben Maimon.

My point in this was to show that women have already been given the title approximating that of rabbi by no less than the Hida (obviously in a pre-feminist context).[10] As far as I know, I was the only one to make this point during the hullabaloo a couple of years ago about the ordination of Sara Hurwitz. I was surprised that no one else picked up on this as I happen to think it would give the pro-ordination side a strong piece of ammunition.

My post went up on June 25, 2010, and someone must have mentioned this to R. Schachter because on July 7, 2010 he responded. You can listen to what he says here (beginning at minute 6). He mentions that the Hida’s use of rabbanit was cited in support of women’s ordination, and concludes that nevertheless this proof is “not so conclusive.” [11]

Flora Sassoon (1859-1936) was an extremely learned woman who lived too late to be included by the Hida.[12] In 2007 the Sassoon family published Nahalat Avot, which is a large collection of letters sent to the Sassoons by great Torah figures. Many of the Torah letters in this book were sent to Flora, and she is addressed in a number of them as “rabbanit”. Her husband held no rabbinic office and I think we can therefore conclude that the term “rabbanit” is being used as a title of respect for her knowledge.[13] Another example of this is seen in how she is introduced by R. Joel Herzog, who published a derashah she delivered in his Imrei Yoel, vol. 3, pp. 204-206. (Are there any other examples of a traditional sefer including something written by a woman?) Herzog too uses the term rabbanit as a title of respect.

Finally, with regard to women’s roles, let me call attention to what I think is a little known fact. Liberal Orthodoxy is very interested in finding ways to expand the opportunities for women to be involved in Jewish rituals. This encompasses everything from reading the Torah and leading Kabbalat Shabbat, to reciting sheva berakhot and reading the ketubah at a wedding. I haven’t yet seen any proposals to have a woman serve as a sandak. This would not be a new practice. R. Meir of Rothenburg writes that in his day in “most places” a woman sat in the synagogue and held the baby during circumcision.[14] In other words, this was the mainstream Ashkenazic minhag. R. Meir opposed this practice and made efforts to uproot it. This opposition was successful and is the background of R. Moses Isserles, Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh Deah 265:11, declaring that a woman cannot be a sandak, because it is peritzut.[15] Yet despite Rama’s comment, my experience is that this is the sort of judgment that the liberal Orthodox are quick to revise. Certainly, the Rama would assume that there is more peritzut in having a woman serve as a hazzan than in holding the baby during a circumcision. Yet for some reason, while the latter has become accepted on the left of Orthodoxy, I haven’t heard anyone speak about instituting female sandakot. (If there are places where women are indeed serving as sandakot, please leave a comment.)

2. In an earlier post I discussed how R. Moses Kunitz’s biography of R. Judah the Prince was censored from a recent printing of the classic Vilna Mishnah. I also included a picture of Kunitz. Here is another, completely unknown, picture of Kunitz.

I found it in the Yeshiva University Archives, call no. 1992.008, and I thank the Archives for permission to publish it here.

In the earlier post dealing with Kunitz, I wrote:

Immediately following Kunitz’ essay, there is another article on the grammar of Mishnaic Hebrew by Solomon Loewisohn.[16] In the very first note he refers to the book of Ecclesiastes, and concludes his comment with והטעם ידוע למשכילי עם. What he is alluding to in this note is that Ecclesiastes is a late biblical book, and thus could not have been written by Solomon. To show this he points to the word חוץ, which in its usage in Ecclesiastes 2:25 is an Aramaism, and thus post-dates the biblical Hebrew of Solomon’s day. To use an expression of the Sages, we live in an olam hafukh. Kunitz’ essay was thought worthy of censorship, and at the same time this note remains in every printing of the Vilna edition of the Mishnah. Yet as I mentioned above, let’s see how long it is before this note, or even the complete essay, is also removed.

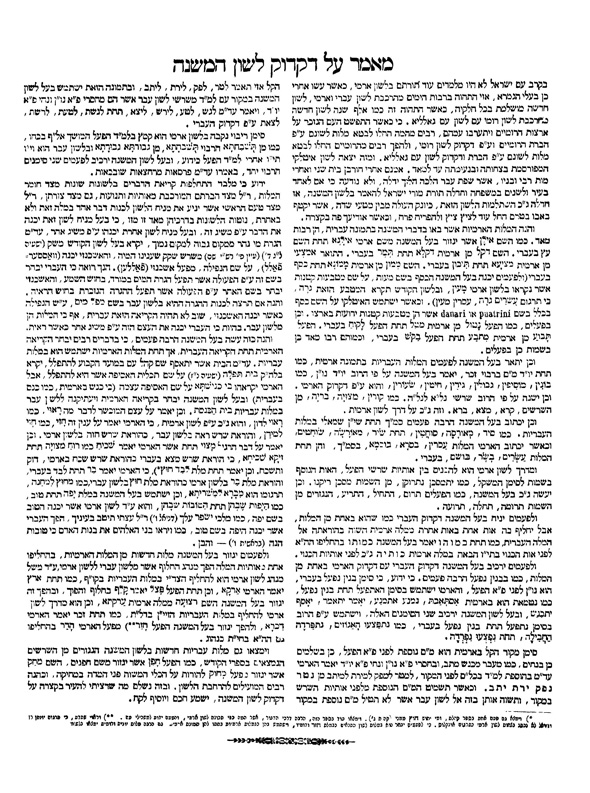

What I didn’t realize, and I thank an anonymous commenter for pointing out, is that this note has already been tampered with, and in such an ingenious fashion that there is now no need for it to be deleted. Here is how it appears in the Vilna Mishnah.[17]

And here is the page in the 1999 Zekher Hanokh edition of the Mishnah, published by Wagshal (an edition which also deletes Kunitz’ introduction).

Now, instead of והטעם ידוע למשכילי עם, we have והדבר ידוע למשכילי עם. In the original, Loewisohn is telling the reader that the reason why there is an Aramaism in Ecclesiastes is known to the wise (i.e., the book is post-Solomonic), In the Zekher Hanokh edition all he is saying is that the existence of Aramaisms in Ecclesiastes is known to the wise, with no daring implication as to dating.

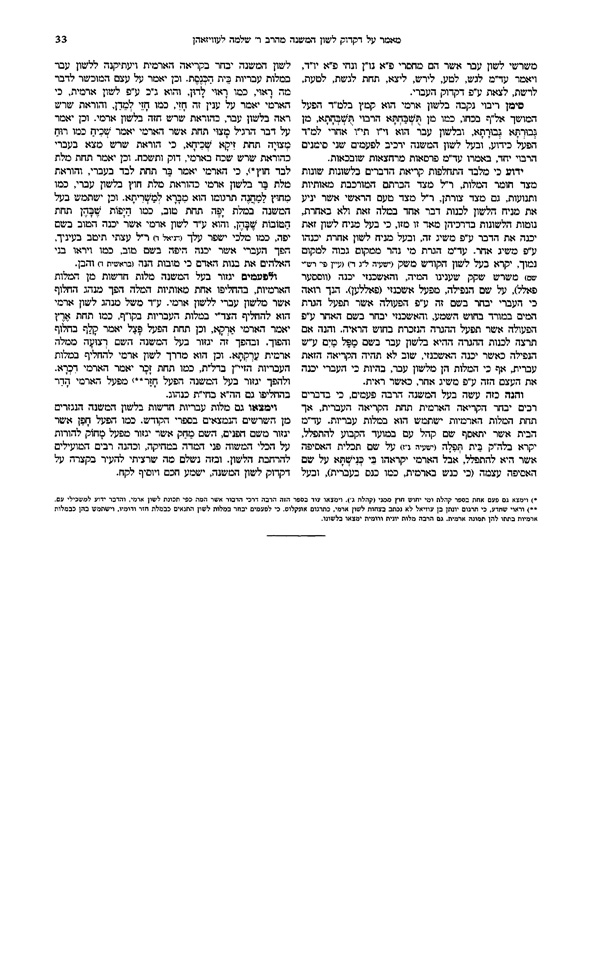

I also found something else of interest. Here is the last page of Kunitz’ essay on R. Judah the Prince.

Notice how he mentions Mendelssohn, Rabe’s German translation of the Mishnah, and how in his opinion R. Judah would be happy with such a translation.

This all sounds a little too “maskilish,” and here is what same page looks like as it appears on Otzar ha-Hokhmah.

Look at what has been removed. Is there really such an edition with the removed lines, or did Otzar ha-Hokhmah censor the material itself? (I will return to the censorship of Kunitz in the next post, as new information regarding this has recently come to light.)

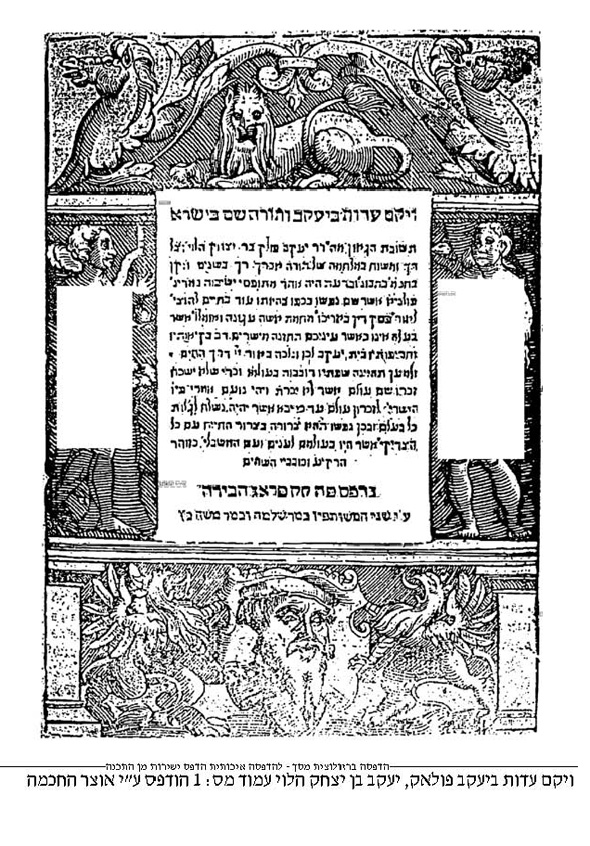

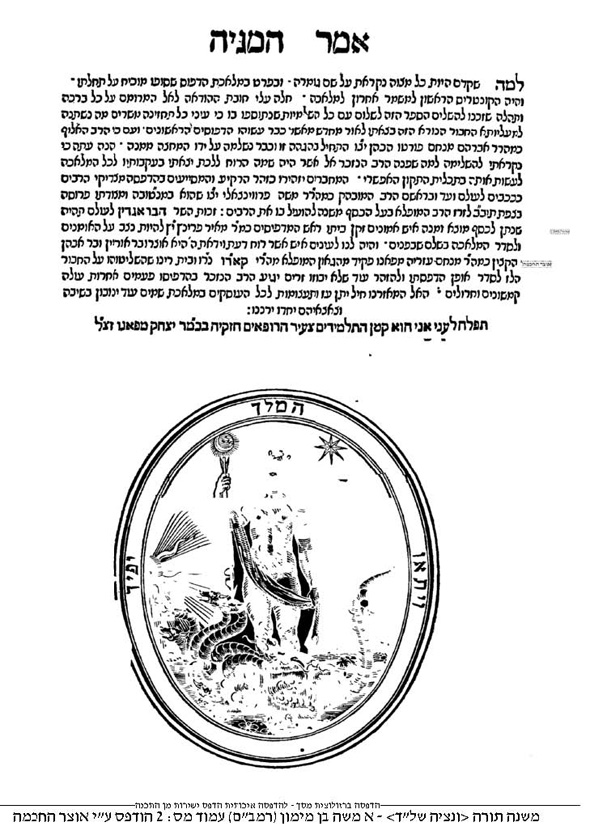

There are other examples where I think it is Otzar ha-Hokhmah that is responsible for the censorship. Here is the title page of the book Va-Yakem Edut be-Yaakov (Prague, 1594) as it appears on Otzar ha-Hokhmah

Here is the uncensored page, as is found on hebrewbooks.org

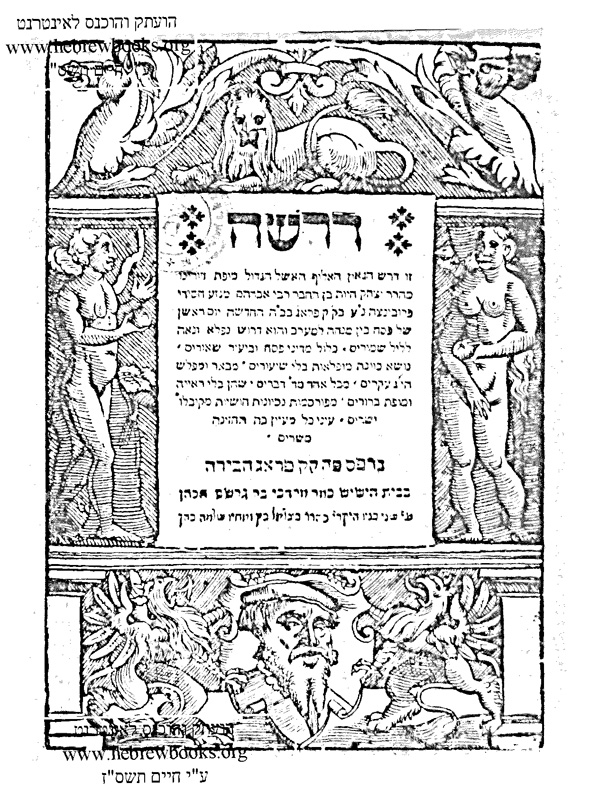

Incidentally, the title page of R. Yitzhak Chajes’ Derashah (Prague, 1589) used the exact same model.

Dan already discussed the Chajes title page here and called attention to how an auction catalog ridiculously suggested, without any evidence whatsoever, that the non-Jewish workers of the Jewish publisher put this immodest picture in.

How were the workers able to get away with this? The catalog has the “religiously correct” answer: it was hol ha-moed and the owner was not around! Since a pious Jew would never have anything to do with such a picture, the non-Jewish workers must have used their own money to buy the plates for this engraving. And why would the non-Jewish workers have spent their own money doing something that would anger the owner and get them fired? It must be that they wanted to cause Jews trouble, which is what non-Jews are always interested in. Knowing that when the owner saw what they did he would never agree to sell a book with such a title page, the non-Jewish workers must have taken all the books from the printing press and, at their own expense, sent them out to all the book sellers. All this could happen without the owner being aware because it was hol ha-moed and during this time the owner of the press wouldn’t dream of dropping by his shop (so much did he trust his workers), just like today none of us know any religious Jews who would ever consider going to work on hol ha-moed.

The title page of Va-Yakem Edut be-Yaakov, published in Prague five years after Chajes’ Derashah appeared, shows us that the non-Jewish workers must have once more, on hol ha-moed of course, surreptitiously inserted the same picture as a title page for a different book. I think everyone has to wonder, why didn’t the publisher learn anything from the first time these non-Jewish trouble makers played around with a Jewish printing press?

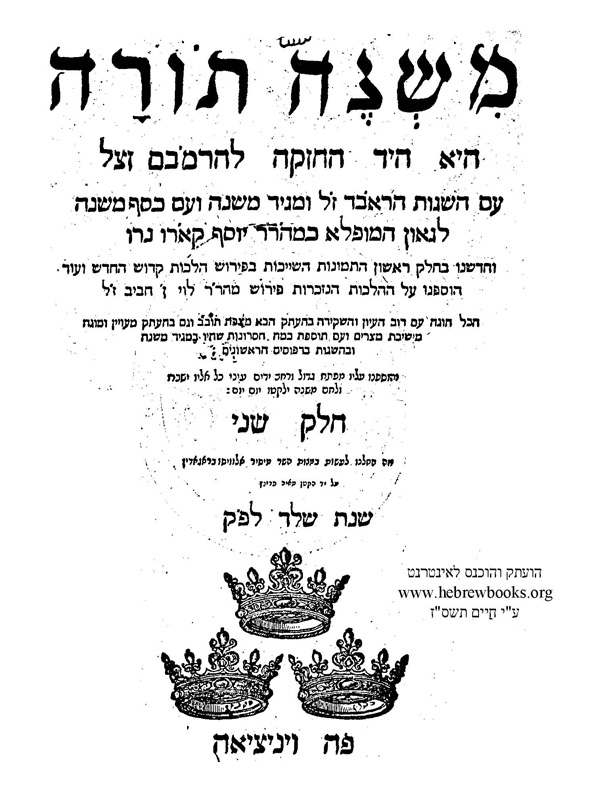

Another example of censorship on Otzar ha-Hokhmah is seen with the Venice 1574 edition of the Mishneh Torah. Here is the title page.

Here is how the second page looks, from volume 2 (as seen on hebrewbooks.org). The verse along the edges is from Psalm 45:12: “The king shall desire your beauty.”.

This edition was published in four volumes. In the copy on Otzar ha-Hokhmah, three of the four volumes contain the second page. Two of the pictures are significantly whited out, and in the second picture below you can see that they have whited out enough so that the reader will think he is looking at a man.

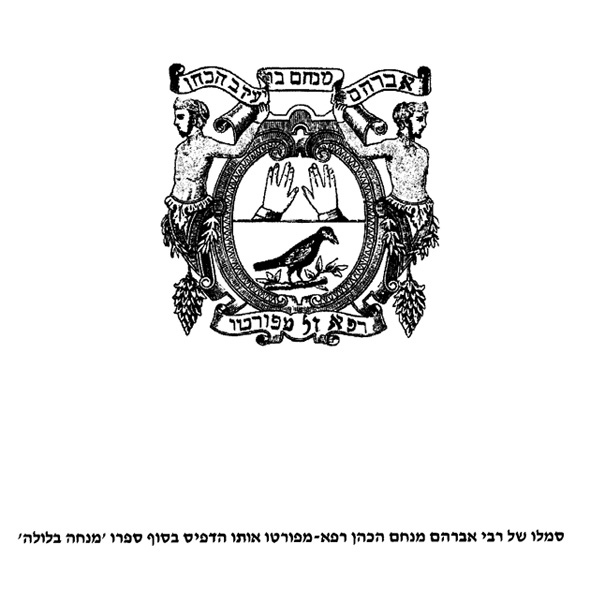

There are, to be sure, plenty of examples where the pictures appear without any censorship on Otzar ha-Hokhmah (and even with the examples I have given, it is not clear if Otzar ha-Hokhmah is responsible for the censorship or the book came to them this way). Here, for example, is the famous family crest of R. Abraham Menahem Rapa of Porto, which appears at the end of his Minhah Belulah.

S. has already pointed out that this picture was altered in a recent printing of the sefer.[18] Here is what the altered version looks like.

Michael Silber has noted that in Binyamin Shlomo Hamburger’s recent book Ha-Yeshiva be-Fiorda, the women have been turned into men, complete with beards![19]

Here is what the Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. Rapoport, writes:

The name Rapa originated in the German Rabe (Rappe in Middle High German), i.e., a raven. In order to distinguish themselves from other members of the Rapa family, the members of this family added the name of the town of Porto, and thus the name Rapoport was formed . . . The family escutcheon of Abraham Rapa of Porto shows a raven surmounted by two hands raised in blessing (indicating the family’s priestly descent).

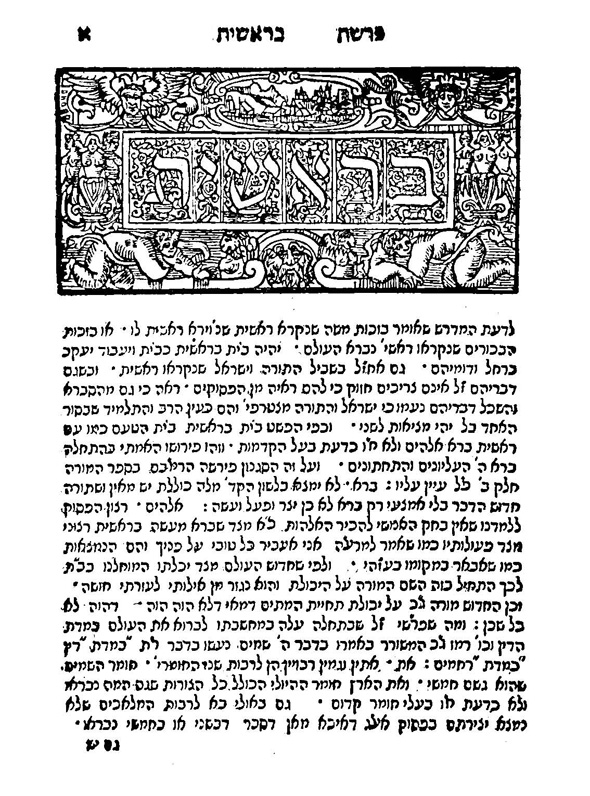

Regarding the sefer Minhah Belulah, at the beginning of each book of the Pentateuch the following “immodest” picture also appears.

As far as I know, hebrewbooks.org has not censored any of the books that appear on the site. (We have previously discussed books that it refuses to put up.) A few years ago the Reich collection of reprints was added to hebrewbooks.org and these have all sorts of interesting title pages. Here is the title page of R. Samuel ben David Ha-Levi’s Nahalat Shivah.

The year is expressed as משיח בן דוד בא. This adds up to 427 (i.e., 5427), and is an allusion towards Shabbetai Zvi. The year 5427 corresponded to 1666-1667, and the convention normally would be to write 1667 (and this is the date given in the Harvard catalog). However, in this case I assume it is more accurate to give the date as 1666. We know that Shabbetai Zvi converted on September 15, 1666. By 1667 this information would have reached Amsterdam and the title page would no longer refer to him as the Messiah. Therefore, I think we can conclude that the book appeared after Rosh ha-Shanah of 1666, but before January 1, 1667. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that if you look at the end of the book there is a comment by the typesetter from which we see that, despite the date on the title page, the book was not actually ready for publication until the beginning of 1668. In other words, the title page was not changed in the interim, despite Shabbetai Zvi’s apostasy.

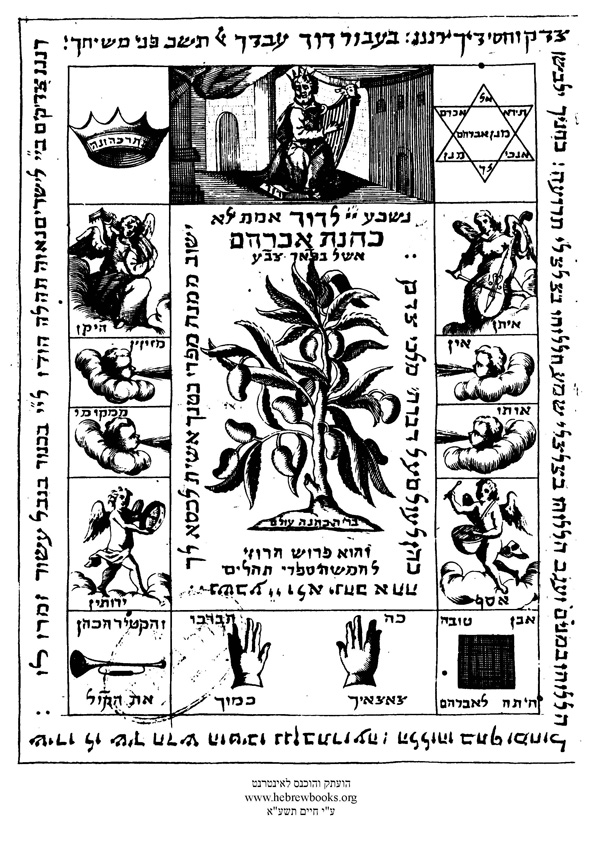

Among the Reich reprints, here is another fascinating title page (actually the first of two title pages in this book). It is from R. Abraham ben Shabbetai’s Kehunat Avraham (Venice 1719).

Here is the author’s picture, that appears on the second page. He clearly is wearing a wig.

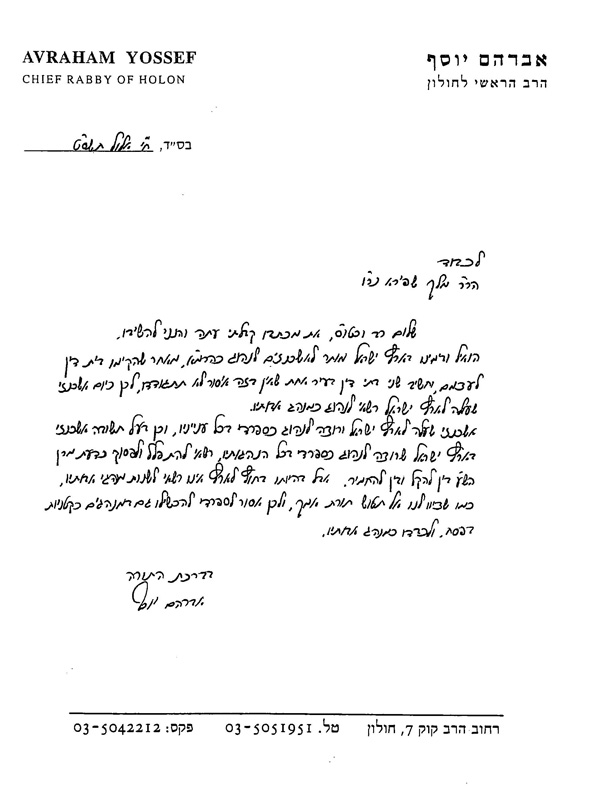

3. In the previous post I mentioned something I was told by R. Avraham Yosef, the son of R. Ovadiah. He is the chief rabbi of Holon and while a great talmid hakham, unlike his brothers R. Yitzhak and R. David he has not published very much. Here is his picture.

Like his father, R. Avraham is known for some controversial statements. He has also surprised people with his viewpoints. See here, for example, where he expressed his support for Livni becoming prime minister. I have found that he is very accessible and will answer any letter written to him. Since we are approaching Passover, let me share with readers the following.

From reading the works of R. Ovadiah Yosef,[20] I have always assumed that in his opinion even Ashkenazim living in Israel are obligated to follow R. Joseph Karo. Despite what R. Yitzhak states in his letter published below, I haven’t seen any convincing explanation as to why the Moroccans and the Yemenites should be obligated in this according to R. Ovadiah, but not the Ashkenazim. And yet R. Ovadiah does not say so openly, perhaps to avoid involving himself in controversy. He also doesn’t say that Ashkenazim should keep their practices in the Land of Israel, except for one issue, namely, kitniyot, where he is explicit that Ashkenazim are obligated to follow their tradition.[21] However, based on my assumptions from reading R. Ovadiah, I assumed that the obligation of kitniyot in the Land of Israel only applied to those who identified as Ashkenazim. If, on the other hand, someone wanted to “convert,” as it were, to Sephardi practice, he would no longer be obligated in kitniyot.

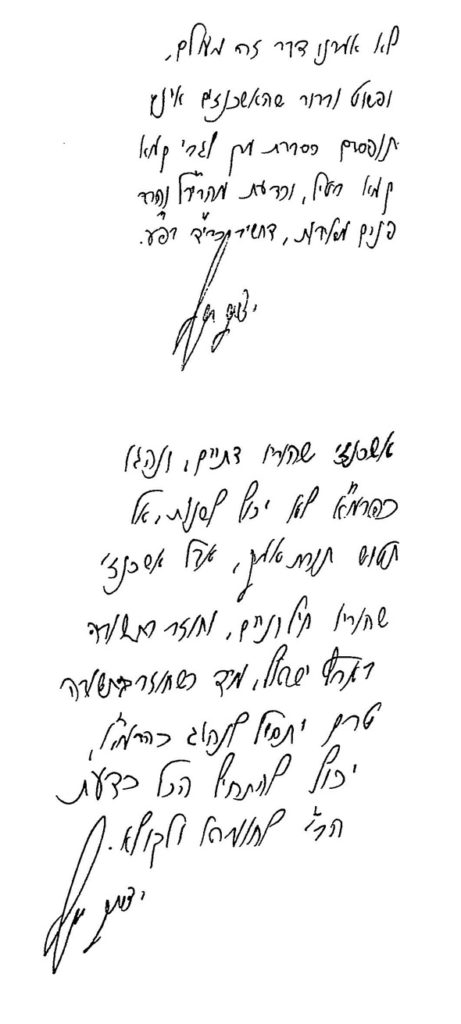

To test my theory, I wrote to three of R. Ovadiah’s sons, R. David, R. Yitzhak, and R. Avraham, asking if it was permissible for an Ashkenazi to adopt Sephardi practices in all areas, meaning that he would no longer have to avoid kitniyot. R. David never replied, but I did receive replies from R. Yitzhak and R. Avraham. Readers might recall how R. David and R. Yitzhak differed about what blessing should be recited over Bamba, and each claimed to have the support of their father. In the kitniyot case as well there is a dispute. R. Yitzhak wrote to me that an Ashkenazi, even in Israel, is bound to his communal practices. The only exception is if he is a baal teshuvah., In this case, he hasn’t yet adopted the Ashkenazic practices, and he can therefore “become Sephardi”. Here is R. Yitzhak’s letter (it was one letter, with two signatures).

However, R. Avraham has a different perspective, believing that he too is properly representing his father’s outlook (and what he writes is what I also assumed based on my own reading of R. Ovadiah). According to R. Avraham, an Ashkenazi in Israel (and only in Israel) is permitted to become Sephardi, בין לטוב ובין למוטב. Here is R. Avraham’s letter.

4. Rabbi Moshe Shamah’s commentary on the Torah has recently appeared. At over one thousand pages, it is titled Recalling the Covenant: A Contemporary Commentary on the Five Books of the Torah. In a future post I hope to deal in more detail with one of Shamah’s essays, but in the meantime I wanted to let readers know about the book’s appearance. Many volumes of Torah commentary appear each year, usually written in the same style. Shamah’s book is different. The sources used and the questions asked will be eye-opening for many. It is not derush and does not psychoanalyze biblical figures. Rather, Shamah’s book is high level Torah scholarship in the tradition of the great peshat commentators, both medieval and modern,. I also found it interesting that the book contains a blurb from the noted biblical scholar Gary Anderson (as well from Yaakov Elman, Barry Eichler, and Jack Sasson).

Just as I was about to send in this post I also received Rabbi Nathaniel Helfgot’s just published Mikra and Meaning: Studies in Bible and Its Interpretation. This is a collection of essays on different themes in Tanakh and is a good example of the Modern Orthodox revolution in the study of Bible. Just as the Rav commented that that it would be impossible today to (successfully) teach Talmud to students who are secularly educated if not for R. Chaim’s approach, something similar can be said regarding Tanakh. For those with a secular education, who have read great books, it is very difficult to connect to Tanakh without the new approach that has been developed in the last forty years or so. As R. Yoel Bin Nun puts in his preface to Helfgot’s book: “It is impossible to study Tanakh in the land of Israel as if we are still residing in Eastern Europe prior to the Holocaust.”[22]

[1] There are, to be sure, opposing passages. See e.g., Bamidbar Rabbah 10:17, where it records that Manoah stated: והנשים אינם בנות הוראה. This text is cited by a number of halakhists to show that women are not to issue halakhic rulings. Both R. Hayyim Hirschensohn, Malki ba-Kodesh, vol. 4 p. 104 and R. Yissachar Tamar, Alei Tamar, Zeraim, p. 151, reject drawing any conclusions from the passage. Both of them claim that one can’t rely on what Manoah said, as he was an am ha-aretz (see Berakhot 61a: מנוח עם הארץ היה). This is an interesting point, but I wonder if it has any validity. It obviously depends on how one is supposed to read Midrash. On the one hand, Manoah may have been an am ha-aretz, but the sage who put this expression in his mouth was not, and neither was the redactor of the text, so perhaps Manoah’s statement should indeed be seen as a rabbinic position. On the other hand, since it was put in the mouth of an am ha’aretz, perhaps it should be regarded as simply that, namely, an uninformed opinion.

It is interesting that the well-known author, R. Aaron Hyman, responded to Hirschensohn in Malki ba-Kodesh, vol. 6, p. 204. He criticized Hirschensohn for writing as if he believed that because the Midrash quoted a statement of Manoah, that the historical Manoah actually said this:

ומה שמביא חתנו הלשון מבמ”ר נשים אינן בנות הוראה, ורוצה אדוני לתלות יען שמנוח ע”ה הי’ אומר דבר זה, חס מלהזכיר שיאמין כבודו שבאמת מנוח אמר דבר זה, האם אמרו חז”ל מדברי נביאות או בקבלה, הלא אך בדרך דרש אמר הדרשן כן וכן והוא דברי הדרשן הי’ מי שהי’ אבל מדרש הוא ואדם גדול קבצם, וכן ידוע כל השקלא וטריא שהיה בין קרח ומשה בענין טלית שכלה תכלת והאלמנה והכבשה, זהו אך מליצה נשגבה אבל לא שבאמת היה כן.

See Hirschensohn’s reply, ibid., p. 209, that his intent was only that the Midrash, בדרך דרש, attributed words to Manoah.

[2] Another irony is that the halakhic textbook written by the most distinguished of these yoatzot turns out to be more stringent, and requires consultation with rabbis more often, than halakhic texts written by men. See Aviad Stollman’s review of Deena R. Zimmerman’s A Lifetime Companion to the Laws of Jewish Family Life in Meorot 6 (2007), p. 5. I can’t imagine that women think that there is an advantage in having halakhic works written by other women if these works actually reduce female autonomy in intimate hilkhot niddah matters and require more consultation with male rabbis.

With regard to calling the women yoatzot and not poskot, Stollman, p. 8, n. 20, believes that “this is merely a tribute to Orthodox political correctness.” Maybe someone who knows the situation better than I can comment on Stollman’s point. That is, are these women really giving halakhic decisions and merely “covering” themselves by using the politically correct term yoatzot?

Regarding Stollman, I should point out that he is an academic scholar, and in addition to articles has published a critical edition and commentary of Eruvin, ch. 10, Ha-Motze Tefillin (Jerusalem, 2008). He has also published a volume of responsa, Pele Yoetz (Jerusalem, 2011). Responsum no. 45 is, I think, unique in responsa literature. Stollman was asked if it is permitted to create Santa Claus dolls that sing Jingle Bells. He rules that it is permissible. If I’m not mistaken, Stollman is the first one since R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg to combine academic Talmud study with the writing of halakhic responsa.

Returning to yoatzot, I think many will find interesting that in Yemen and in some of the Sephardic world there was never a concept of asking a rabbi intimate niddah questions. This was because the women were embarrassed to do so, seeing it as “untzniusdik”. I mention this only because I have heard rabbis say that in truth there are no tzeniut issues with this, and women shouldn’t be embarrassed. They make it seem that it is only due to modern values that all of a sudden this sort of thing is uncomfortable for women. This is clearly not the case, as we see from what happened in the Yemenite and some of Sephardic worlds, hardly centers of modernity. (I am only speaking of the historical reality, not the wisdom of the Yemenite and Sephardic approaches, which usually meant that any doubt would be assumed to render the woman impure.) R. Yitzhak Shehebar, the Sephardic rav of Buenos Aires, writes as follows in his Yitzhak Yeranen, no. 95 (quoted in Beit Hillel, Tamuz 5769), p. 120:

ואשר לעניין מראות הדמים לא נהגנו בזה כלל, כי מעולם לא ראיתי להרבנים באר”צ [ארם צובה] שטפלו בזה, אך הנהיגו את הנשים שכל מראה הדומה למראית אדמומית שהוא טמא, זולתי אם יהיה כמראה לבן או ירוק שהוא טוהר.

Regarding Yemen, R. Yitzhak Ratsaby writes (Piskei Maharitz, vol. 3, section Be’erot Yitzhak, pp. 339-340):

אצלנו בק”ק תימן יע”א אין שואלין כלל לחכמים בעניין הכרת מראות הדמים, ובכל ספק הנשים מחזיקות עצמן טמאות ויושבות ז’ נקיים [ואפי’ לבעליהן נמנעות מלהראות כדי שלא יתגנו בעיניהן . . .] וכ”ה גם ברב ק”ק ספרדים יע”א . . . האידנא דהשאלה בדרך כלל היא רק לעיתים רחוקות, עי”ז נשתלשל הדבר שנמנעו מלשאול לגמרי מחמת בושתן היתירה וצניעותן המרובה כנודע

Ratsaby points out that this practice developed even though talmudic literature provides plenty of examples showing that in the days of the tannaim and amoraim the Sages did examine ketamim.

Regarding Yemen, see also R. Nachum Eliezer Rabinovitch, Siah Nahum, no. 60. In this responsum, Rabinovitch supports the institution of yoatzot and suggests that this practice, of turning to women in niddah matters, even existed in tannaitic times: כי לפנות לאשה חכמה אין חשש שמא תתגנה

In a note to this responsum, the editor provides further testimony about Yemen.

שמעתי עדות מחכם נאמן, שהיו מקומות בתימן בהם היו זקנות שהיו מוחזקות כבקיאות בעניני מראות, והנשים היו פונות אליהן, ומעולם לא ערער אדם על כך.

R. Moshe Maimon called my attention to the Meam Loez’s discussion of the laws of niddah, addressed to both men and women, and there is no mention there of bringing anything to the rabbi. This omission was rectified by R. Aryeh Kaplan, who in his translation (vol. 1, p. 136) adds: “When in doubt, a competent rabbi should be consulted.”

[3] Mishpetei Uziel, Hoshen Mishpat, no. 5.

[4] For sources on women deciding halakhic questions, see the three responsa in support of Sara Hurwitz’ being ordained as a “Maharat,” authored by Rabbis Yoel Bin-Nun, Daniel Sperber, and Joshua Maroof, available here.

[5] The Hafetz Hayyim, who was a “rabbi” if there ever was one, only received semikhah when he was 85 years old, and that was to satisfy a bureaucratic requirement. See Moshe Meir Yashar, He-Hafetz Hayyim (Tel Aviv, 1958), vol. 1, p. 19. According to R. Isaac Abarbanel, rabbinic ordination as currently practiced arose due to Christian influence. See Nahalat Avot, beginning of ch. 6:

אחרי בואי באיטאליאה מצאתי שנתפשט המנהג לסמוך אלו לאלו. וראיתי התחלתו בין האשכנזים כלם סומכים ונסמכים ורבנים. לא ידעתי מאין בא להם ההתר הזה אם לא שקנאו מדרכי הגוים העושים דוקטורי ויעשו גם הם.

[6] The title “rabbi” is indeed significant. This can be seen by the fact that when Sara Hurwitz was called Maharat there wasn’t any outcry, but when she was given the title “rabba” that is when the controversy really broke out, even though her job description didn’t change in the slightest. Does this mean that there was no objection to a woman functioning as a rabbi as long as she didn’t have the title? Only after she was renamed “rabba” did the RCA adopt a resolution rejecting the “recognition of women as members of the Orthodox rabbinate, regardless of the title.” Yet despite that resolution, there are synagogues where women are still serving, for all intents and purposes, as members of the rabbinate minus the title.

[7] Similar, though not identical, perspectives have recently been offered by Rabbis Norman Lamm, Michael Broyde and Shlomo Brody. See Broyde and Brody, “Orthodox Women Rabbis? Tentative Thoughts that Distinguish Between the Timely and the Timeless,” Hakirah 11 (Spring 2011), pp. 25-58. None of them reject the notion of Orthodox women rabbis at some time in the future. From speaking to many people, my own sense is that a majority of the Modern Orthodox community supports women rabbis (although not necessarily pulpit rabbis). When I say “support,” I mean if asked the question, the reply will be yes. But at the same time, the overwhelming majority of the Modern Orthodox world doesn’t care about this issue at all, and this includes women also. However, I believe that the minority will continue to push this issue, and when women rabbis become a reality, the Modern Orthodox will not reject these women or the congregations that employ them, as we can already see at present with Rabba Hurwitz and other female synagogue rabbis (in everything but name). I think this will happen before the natural development of female poskot who, as already indicated, will by definition be rabbis even without a formal ordination.

One more point that needs to be mentioned with regard to women rabbis is the issue of economic fairness. There are significant tax savings, due to parsonage, that an ordained clergyman receives from the government. While it is true that R. Michael Broyde has written that even women teaching Torah are eligible for this even under current tax laws (see here) and a prominent New York law has firm also expressed this opinion, many yeshiva day schools, acting under the advice of their accountants, have refused to adopt this policy. Some sort of formal ordination for women would settle the parsonage question, and give a financial boost to many of our underpaid teachers.

[8] There are, however, a number of very good articles on halakhah written by women. See e.g., Devorah Koren’s article in the recently published Milin Havivin 5 (2011), available here.

[9] Regarding Lieberman, I would like to call readers’ attention to what appears in the latest Yeshurun, vol. 25. On p. 21 the following footnote appears:

“How Much Greek in Jewish Palestine לגרסאות ופירוש תיבות אלה, ראה דברי הגר”ש ליברמן “

Here Lieberman is given the title due a gadol be-Yisrael. Perhaps this can be seen as making up for the censorship of references to Lieberman (and Louis Ginzberg) in an article by R. Mordechai Gifter that appeared in an earlier Yeshurun. See Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox, p. 32 n. 117. After my book appeared, I was informed by one of the editors of Yeshurun that the censorship of R. Gifter’s piece was carried out by the one who prepared the article for print, and the editors knew nothing about this and were upset when they learnt what had occurred.

On p. 632 of the new Yeshurun there is a letter from R. David Zvi Hillman to Prof. Shlomo Zalman Havlin in which he states the following: In the early volumes of the Encylopedia Talmudit Lieberman was referred to as ר”ש ליברמן, a point I noted in Saul Lieberman and the Orthodox. Yet American rabbis protested and insisted that he not be mentioned. These rabbis are identified with the Rabbinical Council of America: מהסתדרות הרבנים ר”ל המזרחניקים. In response to this, R. Zevin from that point on only mentioned the name of Lieberman’s books but not Lieberman himself. A Bar Ilan search reveals that vol. 13 is the last volume where ר”ש ליברמן is mentioned. (Vol. 15 was the last volume to appear in R. Zevin’s lifetime. See Zevin, Ishim ve-Shitot [Jerusalem, 2007], p. 40 [first pagination]).

Why would R. Zevin agree to this? The answer is obvious: money. The Mizrachi in America was an important source of funds for the Encyclopedia Talmudit.

[10] The term “rabbanit” was primarily used for the wife of a rabbi. See Robert Bonfil, Rabbis and Jewish Communities in Renaissance Italy, p. 77 n. 186. My point is only that it was also used for scholarly women.

[11] The continuation of the shiur is also of great interest, as he explains that if one ends up in a hotel on Shabbat and sees that the lights in the hall go one every time one leaves one’s room, it is still permissible to walk in the hallway and it is not even regarded as a pesik reisha.

[12] See the biography and picture of her here. For pictures of Flora and her family, see also here.

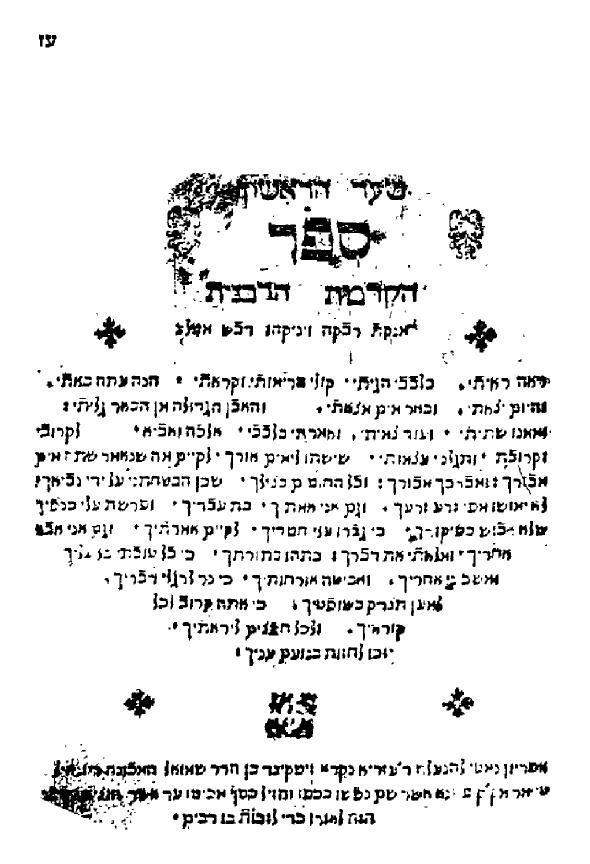

[13] Rivka bat Meir of Prague (died 1605) was another learned woman who was called “rabbanit”, see Frauke von Rohden, ed. Meneket Rivkah (Philadelphia, 2009), pp. 6-7. Rivka authored the Yiddish mussar work Meineket Rivka, published in Prague, 1609. On the title page she is referred to as הרבנית הדרשנית . (In the Altneuschul memorial book it also says that she preached. See Von Rohden, p. 6) Here is the first page of the book, where she is again referred to as “rabbanit”.

Lest anyone misunderstand, I must stress that Rivka only served as a rabbi and preacher for other women, and was therefore not a prototype for twenty-first century women rabbis. My point in referring to her is to highlight the use of the term “rabbanit” as designating a learned woman.

[14] Teshuvot Pesakim u-Minhagim, vol. 2, ed. Kahana, nos. 155-156.

[15] See Daniel Sperber, Minhagei Yisrael, vol. 1, pp. 65-66.

[16] I originally wrote Levinsohn, and thank a helpful reader for the correction. Loewisohn’s essay originally appeared in his posthumously published Mehkerei Lashon (Vilna, 1849).

[17] Incidentally, the note as it appears in the Vilna Mishnah has also been altered from what appears in the original work. In the original it states אשר אינם על טהרת לשון עבר, and in order that people understand what Loewisohn was saying, these words were altered to read: אשר המה כפי תכונת לשון הארמי

[19] See here. As one of the commenters pointed out to this post, the women appear to be mermaids. He helpfully provided this link.

[21] See Yabia Omer, vol. 5, Orah Hayyim no. 37, Yehaveh Da’at, vol. 1, no. 9, vol. 5 no. 32.

[22] R. Aharon Lichtenstein also has a preface to the book, where his ambivalence about the new approach comes through very clearly. This short essay deserves its own analysis.