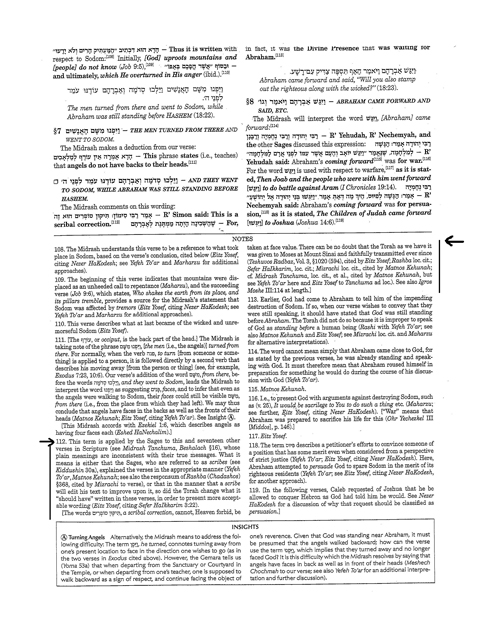

Answers to Quiz Questions and Other Comments, part 1

By Marc B. Shapiro

Question no. 1 was: The word for turkey is תרנגול הדו. There is a dagesh in the dalet. Why? Bring a proof for your answer from Berakhot between page 34a and 38a.

This is correct. The name India (and thus also Hindu) originates with the Persians and Greeks for the land beyond the Indus River. You can see in the Aramaic terms referred to by Heppenheimer that the nun is part of the word. See also the Targum to Esther 1:1 where הדו is translated as .הנדיא Bava Batra 74b, Avodah Zarah 16a, and Bekhorot 37b have other forms of the word, all including the nun.[1] Berakhot 37b refers to נהמא דהנדקא, i.e., “Indian bread.” Targum Ps. Jonathan to Gen. 2:12 translates translates חוילה as הינדקי.

(As to why turkey was referred to by those in Spain, and later the rest of Europe, as “Indian fowl”, that is because when it was first brought back to Europe it was believed to be coming from the area around India, which is where Columbus himself thought that he had ended up.)

For those who are interested in grammatical matters like how the dagesh is used, let me recommend a new book, Adir Amrutzi’s Dikdukei Aviah (Tel Aviv, 2010). In speaking of nuns that drop off, on p. 13 he calls attention to Kiddushin 70a where the word אתרונגא appears. The nun in this word shows us that the plural of etrog is not etrogim, but etrugim, with a dagesh in the gimel and a kubutz under the resh. The singular word etrog should be written as אתרג (All this follows the pattern of tof-tupim [תף-תפים], dov-dubim [דב-דבים]. When the vav holam is in the word, the holam sound remains: חול-חולות, עוף-עופות).

Returning to India, the passage in Berakhot 36b reads: “The preserved ginger which comes from India (הנדואי) is permitted.” The problem is that when you look at Rashi, for his translation of הנדואי he writes: כושיים.

So where does Rashi get the idea that Cushites are Indians? Did he not know that הנדואי means India? In his commentary to Kiddushin 22b he writes as follows:

הנדואה: מארץ כושי כוש מתרגמינן הנדואה

We see the same identification by Rashi in Yoma 81b.[2] Since the book of Esther distinguishes between India (הדו) and Cush, and Rashi identifies הנדואה with Cush, one might be tempted to conclude that Rashi didn’t realize that הנדואה is the same as הדו. But is it possible that he wouldn’t know this?

And to confuse matters even more, in Avodah Zarah 16a, where הינדואה is mentioned, Rashi explains that it means ארץ הדו.

So not only do we have the problem of Rashi identifying הנדואה as Cush, but we also have the problem of consistency, because in one instance he identifies the place correctly. To add one more thing to the mix, in his commentary to Sukkah 36a Rashi states that Cush is further from the Land of Israel than it is from Babylonia. This means that Rashi thought that Cush is to the east of Babylonia. In other words, Rashi does not believe that Cush is Ethiopia.[3]

So where does Rashi get this notion? He actually gives us his source in his commentary to Yoma 34b, where he refers to the Targum to Jeremiah 13:23. This verse famously states: “Can the Cushi change his skin, or the leopard his spots?” If you look at the Targum on this verse Cushi is translates as .הנדואה In the Targum to Isaiah 11:11 Cush is also identified as India.

So again, I ask, what is going on here? How could the Targum translate Cushi as “Indian”?

P. S. Alexander writes as follows: “It was a common view in ancient geography, shared by Ptolemy and probably also the author of the book of Jubilees . . . that Ethiopia was joined to India in the east. It is this idea that lies behind the [talmudic] statement that Cush and Hodu are adjacent.”[4] He also notes that the Indians dark skin was one reason for the identification. Furthermore, Alexander tell us, there was an ancient belief that there was a land connection between Ethiopia and India south of the Indian Ocean.

Since we have been speaking of India,[5] let me share with you what I found in R. Hayyim Hirschensohn’s Nimukei Rashi on Bamidbar (a copy of which I will give out to the winner of my next quiz[6]). On p. 81b he suggests that the revolt in India against English rule was a punishment of England for splitting the Land of Israel when it created Transjordan.

Returning to the quiz, my second question was: There is a rabbinic phrase that today is used to praise a Torah scholar, but in talmudic days was used in a negative fashion. What am I referring to?

Rashi’s explanation should remind people of a phrase used by R. Bahya Ibn Paquda in Hovot ha-Levavot 3:4. In its medieval Hebrew translation it became famous: חמור נושא ספרים. I first heard this expression in yeshiva. Only later did I realize that it came from R. Bahya, and only some time later did I learn that R. Bahya didn’t invent it. Rather, it originates in the Quran 62:5.[7]

* * *

This, incidentally, is not the only time that I assume that Artscroll knows what it is writing is incorrect, but writes so anyway. I have a good example of this in the book I am currently working on, so I don’t want to give it away now. I already noted another example in Limits, where I call attention to the introduction to the Artscroll Chumash which states: “Rambam sets forth at much greater length the unanimously held view that every letter and word was given by God to Moses” (emphasis added). This statement, that the view of the Rambam is unanimously held, is false. Furthermore, Artscroll knows it is false, and in its commentary to Deut. 34:5 it mentions the talmudic view that the last verses were given to Joshua.[8]

Here is another example along these lines that I think readers will find interesting. It comes from the new Artscroll Midrash Rabbah, and was called to my attention by R. Avrohom Lieberman (who already called my attention to the Kalir change in the Machzor).

Since we are now on the subject of Artscroll (the most important and influential Orthodox publishing venture of all time), and lots of people want me to post more on this topic, let me give one final example.[9] It comes from Ecclesiastes, as I dealt with this book in the last series of posts. The upshot of what I and others have already pointed out is something everyone already knew, namely, that Artscroll has a religious agenda. Much like the New York Times’ agenda can be seen not only in the editorial page, but in the news reports as well, so too Artscroll’s agenda is seen not only in the “overviews,”[10] but in the selection of commentaries also. There is enough material for a very long and detailed article spelling all this out.

שרים: משוררים זכרים. ושרות: משוררות נקבות

So now I ask my fair-minded readers: Is Artscroll’s statement that Metzudat Tziyon translates שרים ושרות as “singers” accurate? I think the answer is clearly “no”. Metzudat Tziyon translates the words in question as “male singers and female singers,” and yet—don’t tell me you are surprised—in Artscroll this morphs into “singers”. Why would Artscroll fudge the translation? The answer is obvious. They don’t want people to think that Solomon would have listened to women singing. I am not sure why this is so problematic for them. After all, if Solomon engaged in idolatry (at least according to the biblical text’s simple meaning),, hearing women sing is not so far-fetched. In fact, in his comment on some other words in the verse, R. Jacob Lorberbaum[12] writes as follows):

Lorberbaum, therefore, has no difficulty in seeing the verse as pointing to misdeeds of Solomon.

Let us now see what Kara and Alshich say on the verse, since they too were quoted by Artscroll. Kara’s commentary is printed in Otzar Tov, ed., Berliner and Hoffmann (Berlin, 1886-1887), p. 10: עשיתי לי שרים ושרות: תיקנתי לי זכרים ונקיבות לשורר לפניי

Alshich explains the verse to be referring to משוררים ומשוררות

So we see that the commentators Artscroll refers to are explicit that the meaning of the passage is “male and female singers.”

Among other sources that interpret this way are Kohelet Rabbati, ad loc:

שרים ושרות: זמרין וזמרתא

Yalkut Shimoni, Kohelet no. 968:

See also the Targum to Eccl. 2:8, where שרים ושרות is translated as .זמריא וזמריתא

R. Moses Almosnino, Yedei Moshe (Tel Aviv, 1986), Eccl. 2:8 (p. 58), even explains why the female singers were desirable, as they helped create a better harmony:

על כן אמר שהיו לו שרים ושרות שהם המשוררים והמשוררות, אנשים ונשים יחד, שבהתמזגם יהיו הקולות ערובות, שקול האשה דקה וקול האיש הוא קול יותר עב, ובהתמזגם יחד יצא השיר בנועם.

When the Jews returned from Babylonia to the Land of Israel in the days of Ezra and Nehemiah, the Bible (Ezra 2:65, Nehemiah 7:65) states explicitly that they came with משוררים ומשוררות, “male and female singers.”

As for how Solomon could listen to women sing, for those who feel the need to answer this question, perhaps Solomon agreed with those authorities who feel that there is no blanket prohibition on hearing a woman’s singing voice,[13] a viewpoint that has recently been resurrected by Rabbis Moshe Lichtenstein,[14] David Bigman[15] and Avraham Shammah.[16] According to this perspective, only singing that is sexually arousing is forbidden.[17] Let us not forget that the Talmud speaks of a woman’s voice. It is the post-Talmudic authorities who clarify that this refers to a singing voice, but does this mean any singing voice or only one that in the minds of normal men could be arousing?

R. Marc Angel agrees with the rabbis mentioned in the last paragraph. He writes: “When the prohibition of “kol ishah” is applied to all instances of women singing in the presence of men, this is a distortion of the intent of the halakha. . . . Men and women may sing in the presence of those of the other gender, as long as the songs are of a religious nature, or of a general cultural nature (e.g., opera, folk songs, lullabies).”[18]

R. Yonatan Rosenzweig doesn’t go so far as to permit one to attend a concert with a female singer, but he does say that since today many people are used to hearing recordings of women’s voices, that possibly it is even permissible to watch a woman singing on television.[19]

A number of years ago there were ads in New York Jewish papers for a concert by Neshama Carlebach. The ads stated that the concert was open for women, as well as for men for whom the singing was permissible. This was a very strange formulation. Knowing that R. Mordechai Tendler was Neshama’s posek, I asked him about this. He explained to me that the language originated with him and was based on the notion that the prohibition against kol ishah is not a blanket prohibition, but depends on whether the singing is sexually arousing. (This approach can be supported by the view found in some rishonim that kol ishah that is not sexually arousing is only forbidden during keriat shema. Otherwise, there is no prohibition.[20]) Therefore, men who are used to hear women sing and will not be aroused by Neshama are permitted to attend the concert, and this explains the strange language in the ads.[21] Tendler also told me that this view of kol ishah as being what we can call a “situational prohibition” rather than an absolute issur, was held by his grandfather, R. Moshe Feinstein.[22]

This opinion, that whether or not a woman’s singing voice is prohibited depends on how men will react to it, will no doubt strike some as “unorthodox.” This approach is definitely not as widely held today as in years past. Yet many people reading this post can recall a time when kol ishah, as a general prohibition, was simply not an issue for the Modern Orthodox, or even for many of the more right-wing Orthodox. This was no different than the situation in Germany, where pretty much all of the Orthodox, including members of Hirsch’s community, saw no problem in attending the opera.

If you went back to the 1960s, other than the hasidim and the tiny yeshiva world, it would be hard to find an Orthodox Jew in New York City who didn’t see the Broadway performance of “Fiddler on the Roof.” I would even assume that that there were some roshei yeshiva who saw it. Until the 1980s there was no problem with Modern Orthodox synagogues sponsoring trips to Broadway musicals. My own shul even put on a performance of “Fiddler on the Roof” in the early 1980s. That would be unimaginable today at almost all Orthodox shuls.[23] (Yet somehow YU is able to continue its long tradition of a fundraising night at the opera, and I have not heard of any attempt by the roshei yeshiva to end this practice.)

Until the 1980s, girls would also have solo singing roles in the musical productions put on by many Modern Orthodox yeshiva high schools and summer camps. (Was there a Modern Orthodox summer camp where girls did not sing?) Readers can correct me if I am wrong, but as far as I know, only Ramaz, Flatbush, and SAR still have girls singing solos.[24] The other schools that have girls sing have them do so in groups, or at least with one other girl.

To bring us back to the earlier era, where women singing was acceptable in the Modern Orthodox world, let me quote Rabbi Marc Angel:

R. Eliezer Berkovits wrote:

Nowadays, the singing of a woman is not fundamentally different from what the original Halakhah termed “her regular voice.” A woman’s voice, even when she is singing, is nothing unusual today, and it is no more distracting during the Shema prayer than that of a man singing. Only in specific amorous situations as in the Song of Songs, may it have a sensual quality.[26]

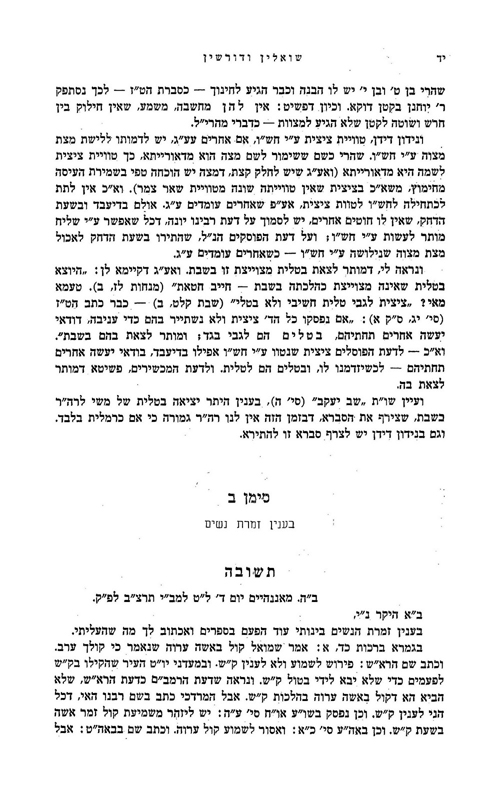

In Between the Yeshiva World and Modern Orthodoxy, p. 216, I quote Jacob Rosenheim who attempts to explain why Hirsch permitted girls to sing at public examinations in the higher grades (and I also note that this passage was censored in the Netzah translation). A halakhic justification of hearing unmarried girls sing was actually penned by R. Isaac Unna, the rav of Mannheim. The short responsum appears in his Shoalin ve-Dorshin no. 2.

In recent generations, poskim have all written that the פנויה referred to here is one who does not have the status of a Niddah, that is, a pre-pubescent girl. The first source to adopt this approach seems to be the eighteenth-century Peri Megadim, Orah Hayyim 75:3. As far as I can tell, none of the early poskim who discuss the matter even mention this point, and they all assume that פנויה mean an unmarried woman, of any age. This approach also continued among certain poskim even subsequent to the Peri Megadim.

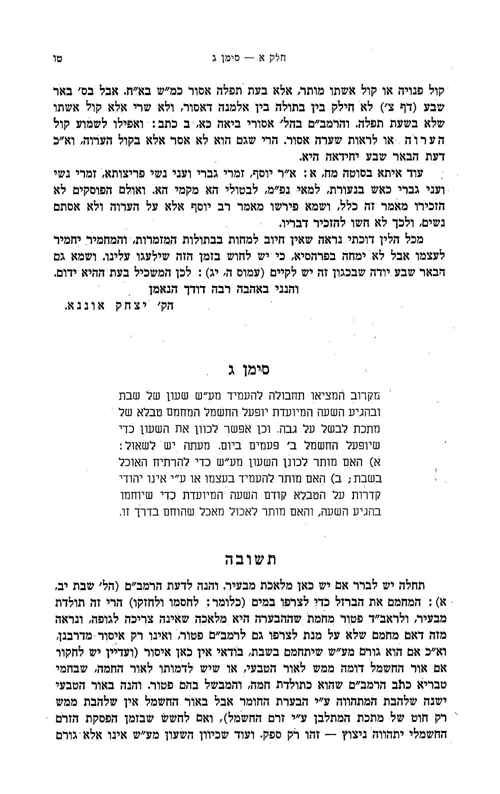

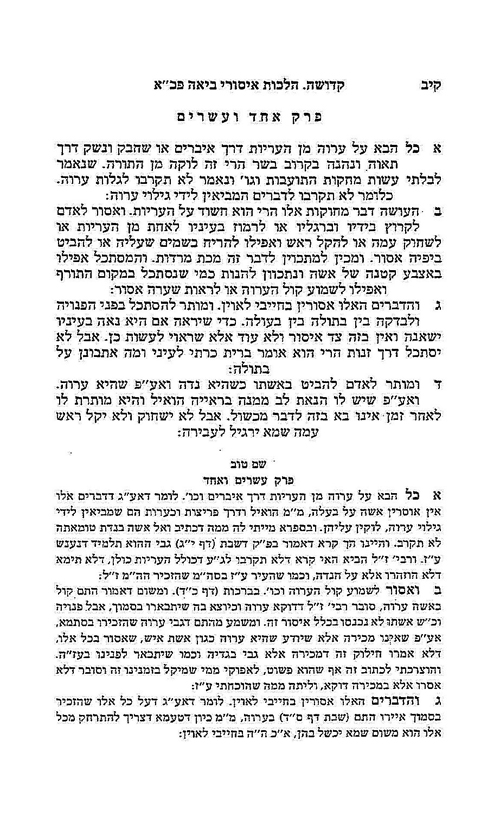

See for example this page R. Jacob Pardo’s Apei Zutrei (Venice, 1797), Even ha-Ezer 21:8:

This is not to say that Pardo approves of listening to single women sing. He doesn’t, and applies to such singing the rabbinic phrase מוטב שיאכלו ישראל בשר תמותות כשרות, which comes from Kiddushin 22a and is stated with reference to something distasteful. It is distasteful, yet permitted nonetheless. Pardo’s careful distinction between what is preferred behavior and what the halakhah actually requires is seen in this comment as well, where he refers to Job. 31:1: “[I made a covenant with mine eyes;] how then should I look upon a maiden?”[29]

הן אמת דלבטל ההרהור יש להחמיר ע”ד ומה אתבונן על בתולה. אך אינו מן הראוי להשוותה לנשואה לאסור מפאת הדין.

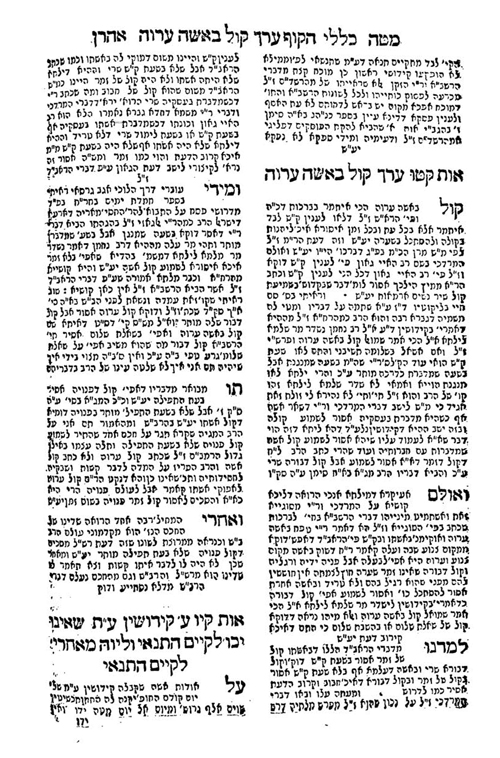

Here is a page from R. Aaron ha-Levi, Mateh Aharon (Salonika, 1820), p. 260b, where we see some more interesting comments, including defending a rabbi who permitted listening to the voice of a single woman.

Returning to German Orthodoxy, Der Israelit was the newspaper of the German separatist community. Yet it seems to have had no problem highlighting an Orthodox female opera singer and stressing her commitment to Orthodoxy.[32] Mordechai Breuer called attention to this last point, and I assume that he didn’t have any knowledge of opera or he would have pointed out that the female singer referred to by the paper, Rosa Olitzka (1873-1949), was quite famous in her day. Here is a picture of her.

Breuer also refers to the JüdischePresse’s review of the opera “Samson and Delilah”.[35] While Der Israelit was the paper of the Frankfurt Orthodox, Jüdische Presse was published by the Orthodox of Berlin.[36]

The view that kol ishah is not an absolute prohibition, but depends on whether or not the singing is sensual in nature, was also held by R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik, at least according to R. Aharon Rakeffet.[37] Rakeffet has also reported on a number of occasions that the Rav attended the opera in Berlin.[38] At the Maimonides School first Hanukkah Banquet in 1939, “the program included Betty Brooks, a prominent radio personality singing a variety of Jewish and English songs, Mabel Wingert, a dancer, and Frost and Helene, society dancers.”[39]

R. Ovadiah Yosef’s viewpoint on kol ishah is also worth noting, especially as it has undergone a change. In the first volume of Yabia Omer, published in 1954, R. Ovadiah deals with the following question (Orah Hayyim no. 6):

Here is how he formulates the question and answer in the table of contents:

Based on this understanding of R. Ovadiah’s responsum, I don’t think there is a contradiction between this teshuvah and R. Ovadiah’s well known love for the music of the Egyptian singing sensation Umm Kulthum.[40] Here is what Umm Kulthum looked like in her younger years.

I was also informed by R. Avraham Yosef that his father, R. Ovadiah, later retracted his ruling in this responsum that if you are familiar with the singer that you can’t hear her voice in shema and tefillah. I later saw that R. Ovadiah himself states as much in Yabia Omer, vol. 9 no. 108:43:

If you hear her voice while you are saying shema or reciting blessings, R. Ovadiah advises וירכז מחשבתו לכוין בברכותיוR. Ovadiah’s words בחיים חיותה במלא קומתה might be taken to imply that even if you know the woman from television, there still is no prohibition of kol ishah.

R. Avraham Yosef states that while it is permitted to hear a woman sing even if you know what she looks like, it is not permitted to attend a live performance or even watch on television. R. Avraham assumes that alllive and television performances are prohibited, not only those that could be sexually arousing.[42] It also needs to be stated that despite how I interpreted R. Ovadiah, that female singing is only prohibited if it is sensual music, the upshot of what R. Ovadiah states throughout his writings is that by definition a live female singer is sexually arousing and thus prohibited. Although I think the evidence shows that R. Ovadiah agrees that theoretically kol ishah is only forbidden if it leads to <>hirhurim >, in practice he assumes that <>alllive female singing falls into this category. (I wonder, however, if he would also forbid the live singing of a very old woman, which would in no way be sensual.)

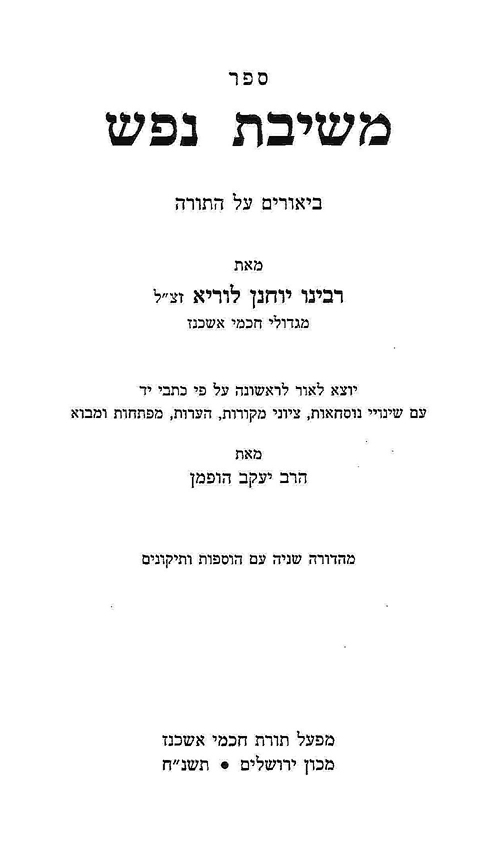

I found another interesting passage regarding kol ishah in the Meshivat Nefesh of R. Yohanan Luria (16th century). On p. 144, after explaining how the women of the desert could sing in front of the men (Ex. 15:21), he writes:

ומזה הטעם ראוי למחות לנשים המשוררות לכלות לפני האנשים רק הבתולות שמותרים בזה כדי לחבב הבחורים לקפוץ עליהם לשם אישות.

He makes the same point on the previous page, and concludes (p. 143):

רק הבתולות ראוי להם שיחבבו עצמם על הבריות לקפוץ אחריהם

What it means is that while married women can’t sing in front of men, unmarried women are permitted to do so in order to attract the attention of the young men, similar to what they did in Temple days when they would dance before the eligible bachelors.

Some might be wondering, how was this permitted since married men will also hear the women sing, and being that they are not in the “market” for a wife, what permission is there for them to listen to and be physically attracted to the young women? I think the answer is obvious, that those men who would have had improper thoughts were not supposed to listen to the women, just as I presume they were not supposed to watch the single women dance in Temple days. Yet the Sages did not ban this dancing because of what some men might be thinking, and similarly, Luria permits the singing by single women and is not concerned that some married men might also be listening. The logic behind Luria’s position is that young men looking for brides are supposed to be attracted to young women. The latter dress up nicely so that the men look at them, they put on makeup for this purpose, and yes, they sing in front of the men, all in order to make themselves attractive.

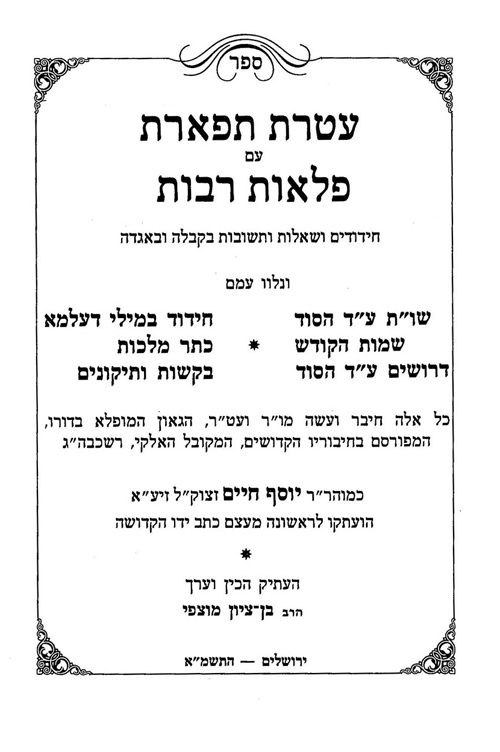

Here is the title page of Luria’s sefer.

He points to an early eighteenth-century communal decree in Altona-Hamburg-Wandsbek forbidding attendance at the opera, except for on Hanukkah and Purim when it was permitted. The text is also found in Simhah Assaf, Ha-Onshin Aharei Hatimat ha-Talmud, p. 116.

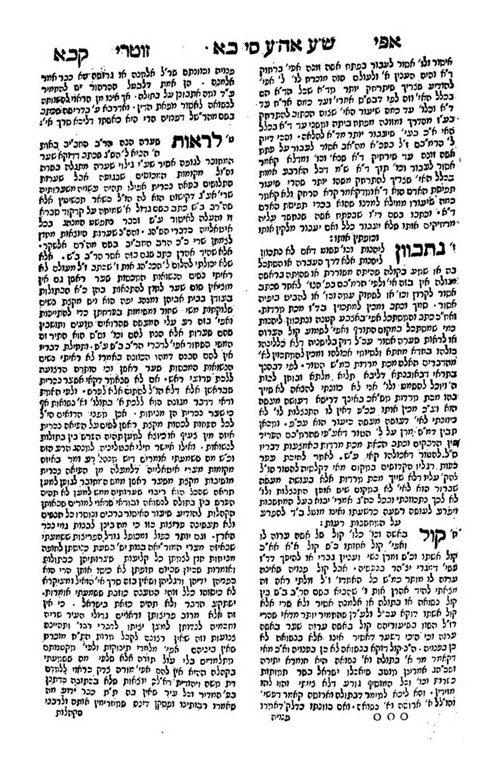

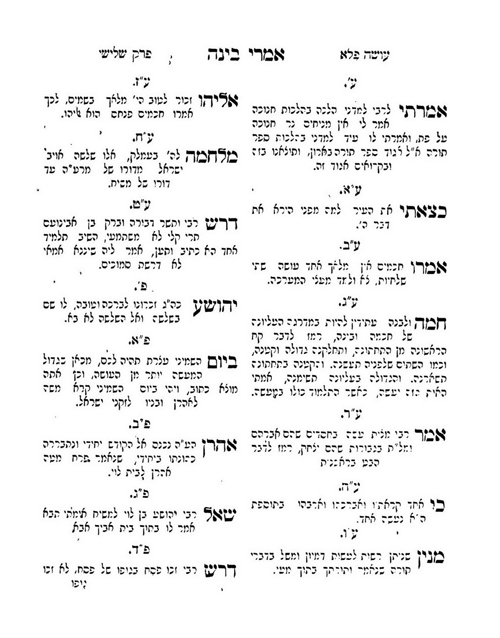

Finally, I would like to point to a very interesting source that as far as I know has never been mentioned in any of the many halakhic articles dealing with kol ishah. I refer to R. Joseph Hayyim’s Imrei Binah, ch. 3, no. 79. Here is the page.

[2] See also his commentary to Isaiah 18:1, where he regards Cush as being in the East.

For the same approach by Rashi, and here too it appears to be his own interpretation (although obviously based on the earlier rabbinic understanding of Cushite), see Sukkah 53a, where it mentions that Solomon had two Cushite servants. Rashi writes:

תרי כושאי: על שם שהיו יפים קרי להו הכי

Incidentally, the Artscroll translation to this passage makes as unfortunate error. While the Talmud speaks of “two Cushites”, Artscroll translates תרתי כושאי as “two Cutheans.”

The Vilna Talmud’s version is תרתי כושאי, while Rashi has תרי. Rashi’s text preserves the correct version (see also Arukh ha-Shalem, s. v. כש, p. 348 n. 4) as תרי is masculine while תרתי is feminine. In R. Meir Mazuz’s new book, Darkhei ha-Iyun, p. 5, he deals with these words and calls attention to the common grammatical error when people write תרתי דסתרי. Since דסתרי(=(הסותרים is masculine, the proper formulation is ether תרי דסתרי or תרתי דסתרן.

For more on the identification of Cushite with ugliness, see Jonathan Schorsch, Jews and Blacks in the Early Modern World (Cambridge, 2004), chs. 3-4, and Abraham Melamed, The Image of the Black in Jewish Culture (London, 2003).

[4] “Toponomy of the Targumim,” (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oxford University, 1974), p. 134.

It contains the Chief Rabbinate of Israel’s acknowledgment that Hinduism is monotheistic. I don’t even think that one can speak of shituf when it comes to Hinduism. What you have in Hinduism are manifestations of the one God, and this does not appear to violate any Noahide commandment. This is significant since in the Jewish imagination Hinduism has often been seen as a classic example of real idolatry. Thus, right at the beginning of many seforim it states that passages dealing with Gentiles are only referring to idolators in places like India.

Related to the latter point, there is an unbelievable error by the great R. Judah Aszod. In 1833 the Hatam Sofer responded to the following query of a Hungarian rabbi: During Christian religious ceremonies that pass through the city, are Jews permitted to put candles in their windows? The fear was that if the Jews don’t do that, their homes would be attacked on Christian thugs (Hatam Sofer, Yoreh Deah, no. 133 [end]). The Hatam Sofer concluded that while it was permissible to indirectly request a non-Jew to light the candle, it is absolutely forbidden for a Jew to do so.

הישראל אסור לעשות וצריך למסור נפש ע”ז

In the Hatam Sofer’s responsum he speaks of the candle lighting that takes place in “India”.

ולענין מה שמסבבים בארץ הודו בע”ז שלהם, וכל הדרים באותו המבוי צריכים להדליק נרות, ויהודים הדרים שם אם אינם מדליקים הם בסכנה מפני ההמונים.

It is incredible is that R. Judah Aszod, Yehudah Ya’aleh, Yoreh Deah, no. 170, takes the Hatam Sofer to really be speaking of India, even though as just mentioned, he was responding to a halakhah le-ma’aseh question from Hungary, not from a rabbi in Bombay! This misunderstanding contributes to Aszod’s lenient decision.

לענ”ד הח”ס דוקא קאי על ארץ הודו שמסבבים בע”ז שלהם . . . משא”כ במדינתינו אינו חק המדינה כ”א באיזו מקומות ולא עפ”י המושל אלא מרשעת שונאי ישראל, והדלקת הנרות אצלם נמי רק אין כוונתם להעביר על הדת כ”א שיהודים ישמחו עמהם וזה מותר משום איבה כברמ”א ביו”ד ססי’ קמח . . . וגם בזה”ז לא עובדי ע”ז הן לא מקרי אליל שלהם עכו”ם כמ”ש הש”ך סי’ קנא ס”ק יז.

ודוחק לומר דכיון דבזמן הזה לאו עובדי עבודת כוכבים הן לא מיקרי אליל שלהם עבודת כוכבים

אם נכנס לעיר ומצאם שמחים ביום חגם ישמח עמהם משום איבה דהוי כמחניף להם ומ”מ בעל נפש ירחיק מלשמוח עמהם אם יוכל לעשות שלא יהיה לו איבה בדבר

[6] As with the other volumes of this series, one can find lots of interesting passages in vol. 4. Here are just a few. P. 56b: Moses opposed the eating of meat, but he could not forbid it because the people would regard this as heresy. P. 98b: Hirschensohn mentions the notion, already expressed by the Vilna Gaon, that sometimes the Talmud’s explanation of the Mishnah is to be understood as a form of derash. In other words, the explanation is not in accord with what the Mishnah really intended. He also refers to Berdyczewski and writes zikhrono li-verakhah after his name. P. 14a: There is no obligation in contemporary times for married women to cover their hair.

וזהוא ההיתר שנוהגים היום ברוב המדינות שהנשים מבנות ישראל הולכות בגלוי הראש, אם שהראשונות שבטלו את המנהג היו נקראות עוברות על דת משה אבל הבאים אחריהם אחרי שכבר נתבטל המנהג אין בזה איסור עוד.

[9] I had been planning to offer one further example, but I was shown to be wrong. Let me explain: A little while ago R. Natan Slifkin had a post on werewolves, citing R. Efraim ben Shimshon’s strange comments in this regard. See here.

Slifkin earlier had written about this in his Sacred Monsters. None of this was a revelation to me since I had earlier seen the material from R. Efraim in R. Yosef Aryeh Lorincz’ Pelaot Edotekha, vol. 2, pp. 136-137. Not surprisingly, Lorincz takes this all very seriously. Readers might recall that I mentioned Lorincz’ book here. I called attention to his discussion of whether it is permitted to eat the flesh and drink the blood of demons. After this post I had a correspondence with someone who wanted to know what I thought about what Lorincz had written. I told him although I don’t know what the halakhah is in this matter, I nevertheless promise to eat the first demon that Lorincz is able to capture. I further told him that I would even volunteer to shecht it. My correspondent wasn’t seeing the comedy in this, as he thought that this was a very serious issue, that someone whom we are told to respect for his Torah knowledge could actually, in the twenty-first century, be discussing such a matter as a real halakhic problem. He was also adamant that if such a book was published by someone who taught at a Modern Orthodox school, the principal should immediately fire the author. Further correspondence revealed that he also didn’t think that anyone who believed in demons should be allowed to teach at Modern Orthodox schools.

My response to him was that I don’t think we need to get all out of shape about demons. To begin with, and readers can correct me if I am wrong, I don’t think that most people in the American haredi world really believe in demons. Yes, I know they study the talmudic passages that refer to demons, and will mention them as the reason for washing one’s hand three times in the morning, but based on conversations I have had with people in the haredi world (admittedly, most of them from the intellectual elite), I don’t think that they take it seriously. (When I say they don’t “believe” in demons, I mean real belief in the role of demons and how they affect humanity, as expressed in the Talmud and elsewhere.) It is almost like the emperor has no clothes, in that they don’t believe it but continue acting as if they do, afraid of what will happen if they are “outed”. (I have found a similar phenomenon with regard to Daas Torah. I have discussed this issue with many people in the haredi world, and have yet to find even one who accepts the version of Daas Torah advocated by so-called Haredi spokesmen and Yated Neeman.) But even if I am wrong in this, there are lots more important things to keep out of Modern Orthodox schools than an occasional reference to demons. How about the negative comments about non-Jews and even racist statements (sometimes under the guise of Torah) that children are exposed to in Modern Orthodox schools? How about rebbes telling the students that there is such a thing as spontaneous generation, which is akin to telling the students to sign up with Flat Earth society?

Getting back to werewolves, there is someone much better known than R. Efraim who refers to them, namely, Rashi. In his commentary to Job 5:23, Rashi explains that חית השדה means werewolf. (He offers the Old French, for which see Moshe Catane, Otzar ha-Loazim, no. 4208, and Joseph Greenberg, Otzar Loazei Rashi be-Tanakh, p. 211) He further adds that this is also the meaning of אדני השדה (See Kilayim 8:5). I have to admit that I was all set in this post to mention that Artscroll, which always cites Rashi’s interpretation, in this example chose to omit it. Without even examining the commentary, I was sure that Artscroll would choose to avoid mentioning anything about werewolves. Yet when I actually opened up the commentary, prepared by R. Moshe Eisemann, I was pleasantly surprised to see that he indeed tells the truth, and the whole truth, i.e.,, that Rashi was referring to a werewolf. I found something else in this volume that I didn’t expect. In an appendix he discusses whether the commentary attributed to Rashi was actually written by him. Unfortunately, Eisemann did not feel that he should inform the reader which academic sources he used in preparing this appendix.

[10] I don’t understand why Artscroll uses this word. The overviews found at the beginning of their books are actually not overviews. (Look up the word if you are not sure what it means). They should have been called what they are, namely, “introductions.”

[11] The Talmud explains sharim ve-sharot as מיני זמר, and Rashi, Eccl. 2:8, clearly based on the Talmud, explains sharim ve-sharot as מיני כלי זמר. Either Rashi’s text of the Talmud also included the word כלי , or this is how he understood the talmudic expression מיני זמר. (Literally, מיני זמר means “types of music”, and when the word כלי is added it means “various musical instruments.”)

[12] His commentary, Ta’alumot Hokhmah, is found in the standard Mikraot Gedolot.

[13] According to R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg, the Rambam’s opinion is that kol ishah is only forbidden if one derives sensual pleasure from it. See Seridei Esh, vol. 2 no. 8.

[14] See here.

[15] See here.

[16] See here.

[17] R. Yuval Sherlo does not permit one to attend the opera, but if one is stuck in a situation, such as a soldier at a military event, then he rules that it is permissible to remain even though women are singing. See here.

[18] Conversations 12 (Winter 2012), pp. 43, 47; also available here. At the end of the article, Angel concludes: “Married women need not cover their hair, as long as their hair is maintained in a modest style. The wearing of wigs does not constitute a proper hair-covering for those married women who wish to cover their hair. Rather, such women should wear hats or other head coverings that actually cover their hair.” He also discusses hair covering on YouTube here.

[19] “Kol Ishah Bimeinu,” Tehumin 29 (2009), p. 143.

[20] See Seridei Esh, vol. 2 no. 8, and see also the helpful summary of positions available here.

[25] Foundations of Sephardic Spirituality (Woodstock, VT, 2006), p. 186.

[26] Jewish Women in Time and Torah (Hoboken, 1990), p. 62. Berkovits also understood the matter of women’s hair covering in the same fashion, and did not regard it as an obligation in contemporary times (heard from Berkovits’ son, Prof. Avraham Berkovits).

I don’t think anyone today assumes that there is a prohibition in seeing the uncovered hair of an ervah, if one is not sexually aroused, the reason being that we see it all the time and are thus used to it. By the same logic, if one is unaffected by hearing a woman sing, even if she is married, there should be no prohibition even according to how I explained the Ba’er Heitev. This is indeed the conclusion of R. Aharon de Toledo, Divrei Hefetz (Salonika, 1795), p. 113a:

[29] The verse from Job is used in an Aggadic sense in Bava Batra 16a and Avot de-Rabbi Nathan, ch. 2, and then used by Maimonides in Hilkhot Issurei Biah 21:3.

ומותר להסתכל בפני הפנויה ולבודקה, בין בתולה בין בעולה, כדי שיראה אם היא נאה בעיניו, יישאנה; ואין בזה צד איסור. ולא עוד, אלא ראוי לעשות כן. אבל לא יסתכל דרך זנות, הרי הוא אומר “ברית, כרתי לעיני; ומה אתבונן, על בתולה”

[30] Commentary on Sanhedrin 7:4. What this means is that one can look at a possible future wife and appreciate her beauty, for after all, one is supposed to be attracted to her. As we have seen already, in Hilkhot Issurei Biah 21:3, Maimonides adds a caveat. He states that is forbidden to look at an unmarried woman דרך זנות. What this means is that while one can look at and admire the beauty of a single woman (what I earlier referred to as “moderate sensual thought), one cannot leer at her, i.e., with lascivious intent.

[31] When Maimonides speaks of enjoying an unmarried woman’s beauty, I am certain that he is speaking of a Jewish woman, whom you can marry.

[32] Breuer, Modernity Within Tradition, p. 150. See Der Israelit, April 5, 1894, p. 503. See my post here, where I deal with the unsubstantiated rumor that Hirsch attended the opera. I quote from Prof. Breuer’s email to me where he writes: “When I went to the opera as a boy of 13-14 years my father [Isaac Breuer] did not express his dissatisfaction.”

[37] Listen to his shiur from Feb. 8, 2010, available here, beginning at 48:20. Rakefet also quotes R. Aharon Lichtenstein that the Rav held that in modern times there is no obligation for married women to cover their hair. Listen to the shiur just mentioned beginning at 62 minutes. I will return to this point in a future post when I deal with R. Michael Broyde’s article on the topic.

[39] Seth Farber, An American Orthodox Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik and Boston’s Maimonides School (Hanover, NH, 2004), p. 165 n. 19.

[40] See Zvi Alush and Yossi Elituv, Ben Porat Yosef (Or Yehuda, 2004), p. 37. See p. 408 that to this day he listens to her music, and see also the testimony to this in Or Torah, Tevet 5770, pp. 383-384. According to R. Avraham Shammah, cantors used her tunes for various tefillot, a practice that continues to this day. See here, p. 10.

המורם מכל האמור דביודעה ומכירה אפי’ ע”י תמונה אסור לשמוע קולה בגרמפון או ברדיו, אבל אם אינו מכירה מותר, ואין בזה משום קול באשה ערוה.