Yom Tov Sheni and the Customs With Regard to Travelers

By J. Jean Ajdler

J. Jean Ajdler of Brussels, Belgium, is a civil and structural engineer. He has published articles about medieval Jewish astronomy, the history of the Jewish calendar, and Talmudic metrology, and is the author of Hilkhot Kiddush ha-Hodesh al-pi ha-Rambam (Jerusalem: Sifriati, 1996).

This is his first contribution to the Seforim blog.

Abstract: In ancient times the customs of the communities were extremely variable the one from the other. Each community had its own customs and it was very jealous of them. Therefore very precise rules ensured the equilibrium between them at the level of the travelers between these communities. The introduction of the printing with the publication of the Shulhan Arukh in the sixteenth century constituted the globalization of the Jewish society and contributed to the standardization of the Jewish rules and customs and the progressive disappearing of the local minhagim. However one great difference between Israel and the Diaspora survived; Israel keeps only one festival day while the Diaspora keeps two festival days. It is today the greatest difference of custom still extant and the dramatic increase of travel has given more acuteness to the problem. The aim of this article is the examination of the rules of priority of the customs in general, and that of the second festival day in particular, at the level of the travelers. We first examine the general problem of the minhagim: we examine the Talmudic sources and their understanding and the consecutive rulings. We acknowledge a great confusion in the understanding of the reference texts and a great diversity in the rulings.

Afterwards we examine the problem of the second festival days with regard to the travelers. In the case of the travelers from Israel to the Diaspora the divergences remain restricted. The Israelis traveling abroad do not keep two festival days but they may not distinguish themselves from the local Jews. The problems still today under discussion are whether the Israelis traveling abroad are allowed to perform work secretly, how they should behave outside a Jewish settlement, how long and under which conditions they can take advantage of their quality of Israelis. As for the travelers from the Diaspora to Israel, It seems even likely that the problem was not grappled with in the Talmud. There is a great confusion among the rulers: the overwhelming majority ruled that the travelers behave completely like in the Diaspora, some ruled that the travelers behave completely like Israelis and some ruled that they should adopt the severity of the two first opinions. We show that the first opinion has also weak points and is not better justified than the two others so that the problem remains theoretically open.

I. Introduction.

Yom Tov sheni shel Galluyyot was definitively instituted in about 325 when the Palestinian rabbis, probably under the leadership of Rabbi Yosi, began to send to Egypt and Babylonia, in advance, the data of the coming year. But at the same time, they invited them to go on keeping two festival days, in order to be able to react in the case of a disruption of the communication of the calendar data. There is much discussion in the rabbinic literature about the status of the second festival day. According to one opinion, the second festival day has the status of a minhag i.e. a custom. It is even an important minhag;

[1] the violator of the second festival day is punished by beating or excommunication by contrast with the violator of a plain minhag.

The institution of the second festival day is characterized by the recitation of the Hallel and of all the benedictions, including the Sheheheyanu, exactly as on the first festival day, although one does generally not recite a benediction on a minhag.

[2]According to a second opinion the observance of the second festival day is the result of a takana obliging us to go on keeping the second festival day as if we were still doubting, as it was the case when the Babylonians did not yet know the fixing of the month.

However the application and extension clauses of the second festival day seem to work like a minhag.

If we paraphrase R’ Solomon Meiri, we can say that yom tov sheni shel galluyyot is a

מנהג דרך תקנה, it is a minhag which was introduced through a formal takana, in other words it is a minhag which was upgraded to the status of a takana. The takana is thus to go on keeping the former minhag.

The difficulty of giving a precise juridical status to the second festival day is probably the origin of the great confusion existing in the application of the rules of the second festival day by the travelers between Israel and the Diaspora and vice versa.

This confusion is still increased by the divergences between the rulers about the laws of the observance of the minhag by the travelers. If it were a pure takana to keep a second festival day outside of Israel, then the observance of this second day would depend only on the geographical localization of the person. As mentioned above the rules of yom tov sheni work also like a minhag and its obligations, as for a minhag, seem more to be “personal obligations” or חובת גברא which follow the travelers in their travels through the customs.

A third element could interfere with the issue. The takana instituting the second festival day was sent to Babylonia and was accompanied by a justificatory message. Indeed we find in the next quotation from B. Beitsah 4b:

והשתא דידעינן בקביע דירחא מאי טעמא עבדינן תרי יומי, דשלחו מתם, הזהרו במנהג אבותיכם בידכם, זמנין דגזרו המלכות גזירה ואתי לאקלקולי.

And now, when we know the fixing of the moon, why are we observing two festival days? Because they sent from Palestine the following order: be careful to maintain the practice of your late parents. It could once happen that the authority enacts [unfair] laws [again the Jews] and you could be wrong [if you observe only one day].

It is thus possible that this message was intended for people living abroad exclusively while people traveling from Babylonia to Israel were perhaps excluded from the beginning on. Indeed there was no danger of disruption of the communications and the information about the calendar for people traveling in Israel. It is thus not certain at all that the takana instituting the second festival day was intended for those people traveling to Israel and staying temporarily during the festival.

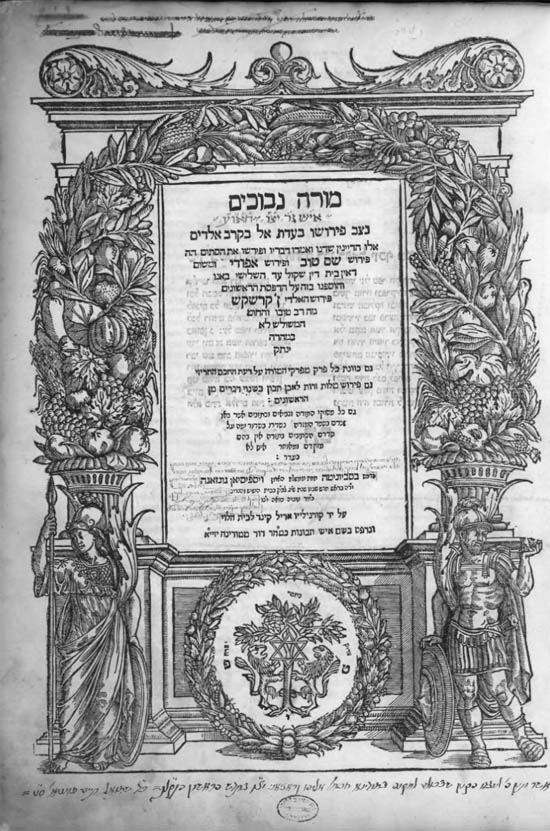

[3]Finally it must be noted that the rabbinic thought was much influences by the position of Maimonides’ ruling that the obligation of keeping two festival days does not depend on the distance from Jerusalem nor from the position of the place in Israel or abroad but it depends only on the exact situation which prevailed at the examined place at the time of the messengers, whether the messengers came along at this place or not. According to Maimonides and some other authorities, in most modern settlements in Israel one should keep two festival days. Therefore, according to these authorities, the obligation of keeping two festival days is not restricted to the Diaspora.

We know also from R’ Estori ha-Farhi (Kaftor va-Ferah chap. 51) that during the fourteenth century the rule was according to Maimonides and therefore they kept two festival days in Ramla but in the neighboring Lod they kept only one festival day.

In B. Pesahim 51b the travel of Rav Safra from Israel to Babylonia was detailed directly after the study of the problem of the traveler between two places having different minhagim. Visibly the Talmud considers that there is a profound analogy between keeping the second festival when traveling from Israel to Babylonia and traveling from a town where they do work on the morning of the 14th of Nissan to a place where they don’t. By contrast we don’t find in the Talmud any evidence about the converse situation of a traveler coming from abroad to Israel. However the overwhelming majority of the rulers considered that the problem of the keeping of the second festival day by the travelers between Israel and the Diaspora and vice versa must be deduced from the rules applicable to the travelers between two towns with different positions about the minhag of working on the morning of the 14th of Nissan. Therefore, in a first stage we will examine thoroughly how the traveler must behave with regard of the minhag during his travels.

II. The Minhag and the Travelers.

A. Talmudic references.

The problem of the minhag and the travelers is raised in many quotations in the Talmud.

1. Mishna Pesahim IV: 1.

Where it is the custom to do work on the eve of Passover until midday [like in the Province of Judah], one may do [work]; where it is the custom not to do [work, like in the Province of Galil], one may not do [work]. He who goes from a place where they work to a place where they do not work, or from a place where they do not work to a place where they do work, we lay upon him the restrictions of the place from where he departed and the restrictions of the place where he has gone; and a man must not act differently [from local custom] on account of the quarrels [which would ensue]

2. B. Pesahim 51a.

When Rabbah bar Bar Hannah came [from Palestine to Babylonia] he ate of the stomach fat. Now Rav Awira the Elder and Rabbah son of Rav Huna visited him; as soon as he saw them he covered it [the fat] from them. When they narrated it to Abaye he said to them “he has treated you as Cutheans.” But does not Rabbah bar Bar Hannah agree with what we learned: “we lay upon him the restrictions of the place from where he departed and the restrictions of the place where he has gone”?

Said Abaye: That is only [when he goes] from [one town] in Babylonia to [another] in Babylonia, or from [a town] in Palestine to [another in] Palestine, or from [a town in Babylonia to [another in] Palestine; but not [when he goes] from a place in Palestine to [another] in Babylonia, [for] since we submit to them [and accept their jurisdiction] we do as they. Rav Ashi said: you may even say [that this holds good when a man goes] from Palestine to Babylonia; this is however where it is not his intention to return, but Rabbah bar Bar Hannah had the intention of returning.

3. B. Pesahim 51b.

Rav Safra said to Rabbi Abba: for instance I, who know the fixing of the month, in inhabitated places I do not work [when I happen to be in Babylonia] because it is a change [which would lead to] strife. How is it in the wilderness? – Said he to him: thus did Rabbi Ammi say: in inhabited regions [of Babylonia] it is forbidden; in the desert it is permitted.

[4]4. B. Hulin 18b.

When Rabbi Zeira went up [to Palestine] he ate there an animal [which was slaughtered in that part of the throat] which was regarded as a deflection by Rav and Samuel.

But does not Rabbi Zeira accept the rule: [when a person arrives in a town] he must adopt the restrictions of the place which he has left and also the restrictions of the place he has entered? – This rule applies only when one travels from town to town in Babylonia or from town to town in the land of Israel, or from the land of Israel to Babylonia; but when one travels from Babylonia to the land of Israel, inasmuch as we are subject to their authority, we must adopt their customs. Rav Ashi said: you may even hold that the rule applies when one travels from Babylonia to the land of Israel, but only when this person intends to return. Rabbi Zera, however, had no intention to return to Babylonia.

5. B. Hulin 110a.

Rami bar Tamri, also known as Rami bar Dikuli, of Pumbeditha, once happened to be in Sura on the eve of the Day of Atonement. When the townspeople took all the udders [of the animals] and threw them away, he immediately went and collected them and ate them. He was then brought before Rav Hisda who said to him: why did you do it? He replied, “I come from the place of Rav Judah who permits it to be eaten.” Said Rav Hisda to him,” But do you not accept the rule: [when a person arrives in a town] he must adopt the restrictions of the town he has left and also the restrictions of the town he has entered.” He replied, “I ate them outside the [city’s] boundary.”

B. The Exegesis of the Mishna.

At the first glance the meaning of the Mishna is evident. There is however a great confusion in the understanding of this Mishna. The great difficulty results from the existence in the Mishna of divergent impositions: laying upon the traveler the restrictions of the place from where he departed and the restrictions of the place where he has gone.

The problem is to decide whether these two impositions must be considered separately, in different situations, whether the one or the other, but not both together or if they must be considered together because they play simultaneously. In this last contingency, we must find genuine situations where both impositions can work together.

1. The understanding of Maimonides (Rambam Hilkhot Yom Tov VIII: 20),

[5] R’ Nissim Gerondi (Ran) (Rif Pesahim 17a: .רבה בר בר חנה), R’ Ovadiah of Bertinoro (commentary on Mishna Pesahim IV: 1) and R’ Isaac bar Sheshet Perfet (Ribash no. 44).

The Mishna speaks about a traveler who does not intend to settle and who will go back to his place of origin. We lay upon the traveler the restrictions of his place of origin when he goes from a place where they do not work to a place where they work. Conversely we lay upon the traveler the restrictions of the place where he has gone when he goes from a place where they do work to a place where they don’t. By contrast if the traveler intends to settle at the new place he adopts the customs of the new place whether these customs are more restrictive or less restrictive. As for the consideration about the necessity that a man must not act differently than the local customs, Abaye considers that this consideration is related to the first case, when the traveler goes from a place where they do work to a place where they do not in order to avoid disputes. By contrast when the traveler goes from a place where they do not work to a place where they do, he really singularizes himself by not working. Rava said that this consideration can also apply to the second case, when the traveler walks from a place where they do not work to a place where they work. Indeed when a tourist walks and does not work and even if the countrymen walk and do not work it is not a singularity.

[6] According to this explanation the two contradictory impositions do not work together, they work separately in different situations.

2. The understanding of Tossafot (B. Pesahim 51a רבה בר בר חנה and B. Hulin 18b הני מילי.), Tur (Orah Hayim 468:4) and R’ Jonathan ha-Kohen of Lunel (Rashba I:337).

The Mishna must be considered as taught in different cases:

[7]n When the traveler does not intend to settle and will go back home, we lay upon him the restrictions of the place from where he departed.

n When the traveler intends to settle at the new place, we lay upon him the restrictions of the place where he has gone.

3. The Provencal understanding (Meiri [Beit ha-Bekhira on B. Hulin 18b and on B. Pesahim 51a and b], Kolbo [end of the laws of Hamets and Matsah] and Orhot Hayim) or the introduction of an intermediate case.

n When the traveler intends to settle at the new place, we lay upon him the restrictions of the place where he has gone.

n When the traveler intends to go back home immediately,

[8] he behaves according to the customs of the place from where he departed. But he is not allowed to behave according to the less restrictive customs of the place from where he departed before people who are not scholars.

n When the traveler intends to go back home later,

[9] then he must behave according to the restrictions of both places; the place from where he departed and the place where he is now staying temporarily.

Meiri writes that this is his opinion and this was also the ruling of his teachers. He found afterwards that Rabad referred to this explanation. He writes also that there are other explanations and even reasoning that the right mind cannot endure.

Thus the Mishna, which speaks of both the restrictions of the place from where the traveler departed and the place where the travelers stays provisory, corresponds to the case of a traveler who intends to go back home after a certain delay (according to Meiri: thirty days). This explanation allows solving the apparent contradiction between Rav Ashi in the quotations 2 and 4. In quotation 2, Rav Ashi understands that the Mishna refers to a case when the traveler does not intend to return home. In quotation 4, Rav Ashi understands that the Mishna refers to a case when the traveler does intend to return home. In fact in both cases the traveler intends to go back home later, after a delay (of more than thirty days). In quotation 2 this situation is considered as if he does not intend to go back home with regard of going back home immediately. In quotation 4, the same situation, going back home after thirty days, is considered as intending to go back home with regard of settling in the new place.

4. There are other explanations of the Mishna but these explanations consider particular situations like going from a place in Babylonia to a place in Palestine or vice versa. These solutions seem farfetched because the Mishna seems to be general and not restricted to very special cases.

[10]C. The ruling of Maimonides (Hilkhot Yom Tov VIII: 20).

The ruling of Maimonides has been at the origin of many discussions about its true meaning.

He who goes from a place where they work to a place where they do not work should not work in a Jewish settlement because of the fear of quarrels but he is allowed to work in the desert. He who goes from a place where they do not work to a place where they do work should not work. We lay upon him the restrictions of the place from where he departed and the restrictions of the place where he has gone. However he should not appear in front of them as if he is idle because of the interdiction to work. A man must never act differently [from local custom] on account of the quarrels [which would ensue].

And similarly he who intends to come back to his place of departure, behaves according to the customs of his place, whether they are more or less severe than the local customs, yet at the condition that he does not do it in front of the local people on account of the quarrels.

This passage is constituted by two different parts. The first part is the transcription of the Mishna Pesahim IV:1

[11] slightly adapted by the introduction of the concepts of settlement and desert which correspond to the influence of the passage about the query of Rav Safra in B. Pesahim. The second part seems similar but it presents differences. The two parts are connected by a coordination conjunction וכן מי that we translated by “and similarly.” The challenge is to explain these two passages and their coordination in the respect of all the Talmudic quotations.

This coordination conjunction means at the first glance “and similarly he who…” But its meaning was fiercely disputed. The use of a computer program shows that Maimonides used this conjunctionוכן מי 62 times in the Hibbur. It is used to connect two passages when the second corresponds to a case leading to a similar, but not necessarily identical, conclusion as in the first passage. He used also וכן כל מי three times but the first passage begins one time also by כל. Anyhow the two expressions seem to have the same signification. When there is no similitude but a real opposition between the two cases Maimonides uses the conjunction אבל מי (36 times in the Hibbur). Therefore the plain explanation of this quotation is to consider that both passages are parallel and deal with the case of the traveler who intends coming back home and not settling in the new place.

1. The Plain Understanding:

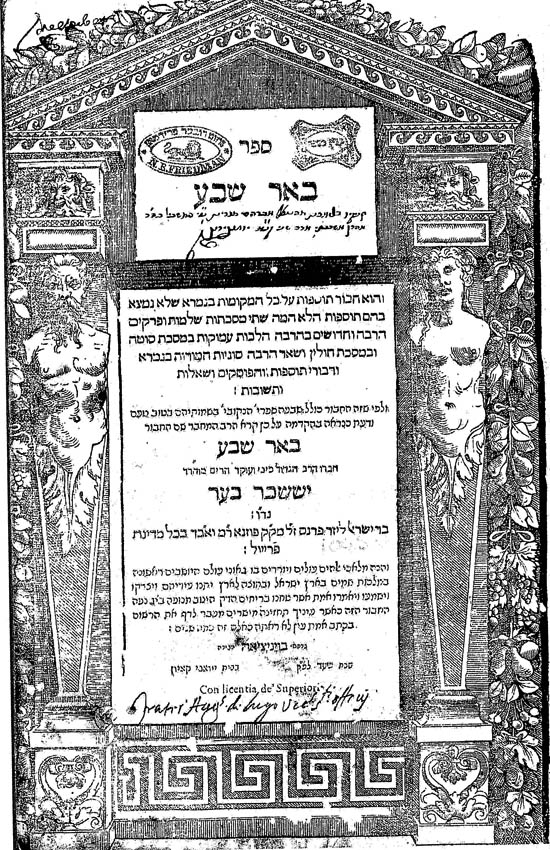

In the first passage we deal with working on the morning of the 14th of Nissan. Apparently working is a special activity that cannot be performed discretely and therefore it is absolutely forbidden. The second passage deals with other customs in general which can be hidden and performed discretely. The difficulty is that Maimonides must choose between the two contradictory statements of Rav Ashi; he accepts the statement of Rav Ashi in B. Hulin 18b that the Mishna refers to a traveler who wants to go back to the place from where he came and, although he rules like Rabba bar Bar Hanna he must reject the statement of Rav Ashi in B. Pesahim 51a; this remains also a difficulty. (Maimonides rules like Rabba bar Bar Hanna but rejecting the answer of Rav Ashi, he has no answer to the objection of the Talmud.) The great commentator R’ Nissim on Rif (Rif 17b entry רבה), and R’ Isaac bar Sheshet (Teshuvot, no. 44) understood the Talmudic passages according to this understanding, giving precedence to the statement of Rav Ashi in Hulin 18b. Among later authorities Magen Avraham, Ba’er Heitev, Be’er ha-Gola and Mishna Berura adopted the same understanding of this quotation of Maimonides, recopied in Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayim 468:4.

2. The Second Understanding:

A second understanding, at the first glance surprising, is to consider that the first passage and, necessarily, the Mishna deals with someone who will settle in the new place and not come back. By contrast the second passage deals with a traveler who will come back to the place from where he came. The consequences of this understanding are surprising and moreover not accepted by the halakha. Indeed, according to the first passage people settling in a new place must behold the customs of their place of origin all their life.

[12] A consequence of this ruling would be that people coming from the Diaspora and settling in Israel would be obliged to go on keeping two festival days all their life. Conversely people coming from Israel with the intention to settle abroad would be allowed to perform work on the second festival day before reaching a Jewish settlement.

[13]This understanding was first championed by the Maggid Mishneh who considered that the first passage correspond to the case when the traveler wants to settle without the intention to come back. He must give the precedence to the statement of Rav Ashi in Pesahim 51a and reject the statement of Rav Ashi in Hulin 18b. This position was followed by Gra, Hok Yakov, Shakh (on Yoreh Deah 214) and Peri Hadash in their commentaries of Maimonides’ quotation in Shulhan Arukh Orah Hayim 468:4.

D. The ruling of Meiri, Orhot Hayim and Kolbo.

Their ruling is consistent with the Provencal understanding explained above, introducing a third intermediate case. It is important because it was influential. R’ David ibn Abi Zimra ruled according to this opinion in a responsum (Radvaz IV: 73 also called no. 1145) about the travelers from Palestine to Egypt.

[14] It was for him the only manner to solve the contradiction between the two statements of Rav Ashi in B. Hulin 18b and B. Pesahim 51a.

In this responsum Radvaz distinguished three cases:

n Going back immediately.

n Going back later.

n Settling definitively.

R’ Joseh Karo copied this ruling of Orhot Hayim in Beit Yoseph (Tur Orah Hayim 496) and abridged it Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayim 496:3.

E. The Ruling of Tur.

His ruling is consistent with the ruling of Maimonides according to its plain understanding (opinion 1).

F. The Ruling of R’ Yoseph Karo in Shulhan Arukh.

Shulhan Arukh raised the issue at four different places.

[15] Of special interest is the ruling of Orah Hayim 468:4, where he recopied the text of Maimonides (Hilkhot Yom Tov VIII:20, mentioned above), which seems to contradict the other rulings and more specifically Orah Hayim 496:3. It is accepted that the ruling of O.H. 468:4 is an abridged version of the original text of Orhot Hayim. We are dealing in this chapter with working on the morning of the 14th of Nisan and therefore the abridgment of the text of Orhot Hayim makes sense because it is forbidden to perform work whether the travelers comes back immediately or later. Therefore the text mentions only two cases, settling in the new place or going back to the first place without making the difference between going back immediately or later. But finally he never mentioned clearly in Shulhan Arukh the existence of three cases so that the doubt subsists about his definitive ruling; does he rule like Orhot Hayim, which he copied in Beit Yoseph O.H. 496 or does he rule like Tur and Maimonides (opinion 1)? Similarly the commentators differed about the meaning of the ruling of Orah Hayim 468:4 where he copied Maimonides.

[16]Anyhow the position of R’ Karo in Shulhan Arukh is problematic because he quoted two contradictory passages of two different authors.

[17]III. The Second Festival Day and the Traveler Going from Palestine to the Babylonia:

The quotation in B. Pesahim 51a about Rav Safra is generally considered as referring to his travel from Palestine to Babylonia. This is indeed the only plausible manner to understand how Rav Safra knew the fixing of the month before undertaking his travel.

[18] Furthermore he asked his query to Rabbi Abba, a Palestinian Amora; this could only be before his undertaking of a travel to Babylonia.

There is a great unanimity between the rulers that in the direction Palestine-Diaspora, the obligation of keeping the second festival day is a personal obligation. Therefore Palestinians traveling to the Diaspora are not subjected to the obligation of the second festival day. However they are forbidden to perform work

[19] on the second festival day when they are in a Jewish settlement. Outside of the techum around the town of this Jewish settlement they are allowed to perform work.

[20]Nowadays the dramatic increase of the travels is the cause of new responsa about the behavior of Israelis abroad. Because of the modern social conditions, with Israelis on mission abroad for one or even many years can prevail themselves of their status of Israelis, the tendency is to lengthen the delay allowing to prevail of the status of Israelis and even to be lenient about the interdiction of performing work discretely. However the rulers do not put at all the emphasis on the absolute necessity for Israelis abroad to behave officially as if they kept two festival days, as it is strictly required by the halakha. In weak communities, where a part of the attendance of the festival office is composed by Israelis (teachers and member of the Israeli mission), their absence at the offices on the second festival day is a very detrimental singularity. The danger is not anymore a possibility of dispute; it is the whole institution of Yom Tov Sheni which they endanger.

IV. The Second Day Festival and the Traveler Going from Babylonia to Palestine:

It is generally considered that this case was not considered in the Talmud and therefore we have not a model case which could allow solving the problem from the first source. However two important Rishonim have understood that the passage about the travel of Rav Safra in B. Pesahim 51a refers to a travel from Babylonia to Palestine.

[21]A. Foreigners Traveling to Israel Behave as in the Diaspora and keep two festival days.

The overwhelming majority of the rabbis compared the problem of the second festival day by the visitors of the Diaspora traveling in Israel to that of the observance of divergent minhagim between two different places. In responsa Yabi’a Omer VI: 40, we find an exhaustive enumeration of the main rulers championing this opinion. This approach considers that the foreigners keep two festival days abroad while Israelis keep one festival day in Israel. The case of the foreigners on a visit to Israel is solved according to the rules of the precedence of the minhagim. In other words, it seems that this particular problem had not been solved by the order sent from Israel to the Diaspora to go on keeping two festival days. In fact this comparison is strange because the status of the second festival day is certainly higher than a minhag like working on the morning of the 14th of Nissan, it seems more comparable to working on the same day after noon. Furthermore, if the behavior of the foreigners on a visit in Israel is regulated by the rule of the precedence of the minhagim, of rabbinic order, we can object that the positive obligation of tefilin of Torah order should have the precedence on this rule of rabbinic order.

[22]Therefore the responsum written on this issue by R’ Moses Feinstein shows originality and distinguishes itself from the others. He accepts the principle that during the period of the observation calendar, a foreigner visiting in Palestine had no doubt any more in the whole Diaspora about the true festival day and kept only one festival day. Now he says, after the institution of the second festival day, we have no more any doubt about the true festival day and we must however keep the second festival day although we know that it is a weekday. This obligation is personal and not territorial, there is no difference whether the foreigner is abroad or on a visit in Israel. As today we know all the fixing of the month, there is no more difference between Israel and abroad as it was the case before the institution of the second festival day.

In other words, according to this responsum, the obligation for the foreigner visiting in Israel, to keep two festival days derives directly from the order sent to the Diaspora, to go on keeping the customs of their elders and observing two festival days. Therefore the obligation is of the same nature than that of the foreigners living abroad and this explains why there are exempted from tefilin on this second festival day. The consequence of this special situation, as noted by R’ Moses Feinstein in his responsum, is that the condition of the foreigner visiting in Israel appears to be more sever today than at the epoch of the observation calendar.

However:

n Where does he know from that the obligation of keeping two festival days is personal and has not a territorial aspect?

n It seems that this responsum is based on the generally accepted explanation that the fear of forgetting the Thora and the rules of the calendar, which was the justification of the institution of the second festival day, exists not only abroad but also in Israel and therefore the order sent to the Diaspora is still valid in Israel. The only difference is that this order was not addressed to the Israelis. Now, as soon as we explain that in reality the fear was about the disruption between Israel and the Diaspora, it no more evident that the order was applicable upon the foreigners visiting in Israel.

n The fact that the conditions of the foreigner on visit in Israel would be more severe today than at the time of the messengers is problematic. Indeed Maimonides had met a similar situation about the late Eruv and he was objected by all the commentators, beginning with R’ Abraham ben David.

[23] The argument was that the situation could never be more severe after the Takana than before. This principle was accepted by all the rulers and the Shulkhan Arukh did not follow Maimonides. Therefore the argumentation of R’ Moses Feinstein remains problematic.

[24]B. Foreigners traveling to Israel behave as Israelis and keep one festival day.

It is important to examine the commentaries of R’ Hananel and Ravan. Indeed these two authorities are generally considered as belonging to the supporters of the first opinion. Or analysis will show that they are supporters of the second opinion.

1. R’ Hananel.

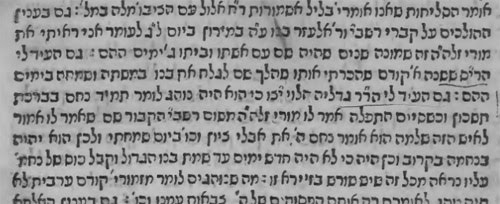

R’ Hananel explains the passage as follows:

“In my situation, when I know the fixing of the month and the people of my place keep two festival days, when I want to come up from Babylonia, where we observe two festival days, to Palestine, where they observe only one festival day, in a settlement [in Palestine] I don’t observe the second festival day,

[25] but in the desert [of Palestine where I am alone without other Jews, and I know for sure that the second festival day is a weekday] how should I behave?

[26] Am I submitted to the strictness of the place from where I came? Rabbi Abba answered him: this was the ruling of Rabbi Ami. Among a Jewish settlement [in Palestine] it is forbidden [to observe the second festival day] but in the desert of Palestine it is allowed.

[27]Critical examination of this interpretation.

n Just before the passage about the query of Rav Safra occurs in the Mishna the passage: “the one who goes from a place where they do (“osin”) to a place where they do not perform (“ein osin”) work. The verb “osin” means to perform work and does not mean to observe the second festival day.

However the following references support the interpretation of R’ Hananel:

Kiddushin 31a: “avidna yoma tava le-rabanan.”

Kiddushin 39b: “de-avdin lei yom tov.”

[28]n Second, Rav Safra, in a settlement in Palestine does not observe the second festival day, why? Even if one is not allowed to distinguish oneself because of the fear of dispute, why should one not be allowed to respect discretely the second festival day according to the opinion of Rava? Rava has indeed said that the fact of walking idly (as opposed to walking with a purpose) is not to be considered as a singularity because there are always people in the streets and the market walking idly.

However R’ Hananel does not seem to have the reading “because of the fear of dispute” as in our Talmudic text. It is also likely that the reason why Rav Safra keeps only one festival day in a settlement in Palestine is because the messengers come along at this place and the people know the fixing of the month. He keeps only one festival day because otherwise it would appear as “mossif.” In the desert of Palestine, where the messengers don’t come along, keeping two festival days does not seem as “mossif.”

n Third the interpretation given for “be-yishuv assur, be-midbar mutar” is difficult.

In the desert, one is not allowed to observe the second festival day. One is either obliged or forbidden to observe a second day, but certainly one is not merely allowed.

However “mutar” could be the formal opposite of “assur”; but it would not mean

that he is allowed but he is obliged to keep two festival days in the desert.

Another possible explanation of the passage of Rav Safra could be the following:

Rav Safra says that he is not performing any work on the second festival day in a [Jewish] settlement [in Babylonia,

[29] although he knows the fixing of the month]. He doubted however, when he is in the desert [of Palestine, i.e. when he has already reached Palestine but did not yet reach a settlement] whether he is forbidden to perform any work because of the severity of the place from where he came, or if he is allowed to perform work in the desert [of Palestine because he knows the fixing of the month]. Rabbi Abba answered: this was the ruling of Rabbi Ami, in a settlement in Babylonia it is forbidden to perform work; in the desert of Israel it is allowed.

We could then conclude that in a settlement in Palestine, where the messengers came along and all the population knew the fixing of the month, Rav Safra was, a fortiori, allowed to perform work on the second festival day and was not submitted to the severity of the place whence he came from.

This second interpretation is also acceptable; it solves the difficulties of the first interpretation but it introduces new difficulties:

n Why must Rav Safra mention that in a settlement in Babylonia he is not allowed to perform work on the second festival day?

In fact Rav Safra knows the fixing of the month and he could have imagined performing work discretely.

n Why is Rav Safra allowed to perform work in the desert of Israel and is he not submitted to the severity of the place from where he came as he is a traveler and intends to go back home?

Apparently in the desert of Israel, by contrast with Babylonia, the fact that he knows the fixing of the month is sufficient to allow him working on the second festival day.

The difference between these two interpretations is the status of Rav Safra in the desert of Israel: according to the first interpretation he keeps two festival days in the desert, according to the second interpretation he keeps only one festival day in the desert.

We will however see that the text of Ravan, although very similar to that of R’ Hananel, must necessarily be understood according to this second interpretation of the commentary of R’ Hananel.

2. R’ Abraham bar Nathan (Ravan).

Ravan often follows the commentary of R’ Hananel; this is also the case here. However, we note some minor, at the first glance, differences. They have a decisive influence of the interpretation.

Ravan writes: “I, who know the fixing of the moon and the people of my place hold two festival days, when I travel to Palestine, where they hold only one day, in a [Jewish] settlement in [Babylonia]

[30] I do not perform work [on the second festival day] because of the strictness of the place where I am.

[31] In the desert of Palestine, am I allowed to perform any work during the second festival day, which I know is a weekday because of the severity of the place from where I came or not? Rabbi Abba answered: this was the ruling of Rabbi Ami. In a [Jewish] settlement [in Babylonia] it is forbidden to perform any work, in the desert [of Palestine] it is allowed. As Rav Safra

[32] asked him about the desert in Palestine, we can conclude that in all the places of his land [Babylonia] it is forbidden [to perform work on the second festival day].”

[33]Thus in the desert of Israel and a fortiori in any settlement in Israel, Rav Safra was allowed to perform work on the second day of the festival.

In the case of a normal person who did not know the fixing of the month it is likely that in the desert of Israel he would not be allowed to work on the second festival day but in a settlement in Israel he was certainly allowed.

3. Conclusion.

The conclusion is clear: R’ Hananel and Ravan agree that Rav Safra was allowed to perform work on the second festival day when he was staying in a settlement in Palestine

[34] during one of his travels from Babylonia to Palestine.

[35] However in the desert of Israel the situation is less clear: according to Ravan he was allowed

[36] but as for R’ Hananel the answer depends on the interpretation adopted.

[37]However all the other authorities

[38] wanted to conclude that R’ Hananel and Ravan impose the keeping of two festival days by the travelers in Israel.

4. The responsum of Hakham Tsevi.

[39]You asked me about people of the Diaspora traveling to Israel; how should they behave during the festivals, like Israelis or like foreigners?

According to my humble view they must observe the festivals like Israeli people and this [matter] must not be considered as a severity of the place from where they came.

Not only this is the case for prayers, benedictions and Torah reading which are in fact no severities of the place from where he came; indeed if someone wants to adopt a more severe conduct and pray the prayer of the festival when it is not the time of this festival, he commits a transgression. But even on the level of the performance of work on the second festival day during their stay in Israel they are allowed. Indeed if all the inhabitants of the traveler’s place would settle in Israel they would certainly be forbidden to keep two festival days in the same way as someone who sleeps eight day in the sukkah is beaten. The same rule is valid for Pesah and Shavuot: if someone keeps an additional day he transgresses the interdiction of “bal tossif”. The rule that they gave “we lay upon him the severity of the place from where he came” is only valid in the case when the people living in the place of the severity are allowed to observe their more severe behavior even if they settle in the place of the leniency. But if they are forbidden to observe their more severe behavior in the place of the leniency, we do not impose this rule. Even the original statement [which represents the basis of the modern institution of Yom Tov Sheni] that they sent from Israel: be careful to maintain the practice of your late parents. It could happen that the authorities enact [unfair] laws [against the Jews] and you could be wrong [if you observe only one day] is only valid abroad. The possibility to be wrong because of the disruption of the communication of the calendar] exists only in their country outside of Israel but when the traveler is in Israel he cannot be wrong!

Now in Israel it is forbidden to add a festival day and Israeli people cannot add one day with regard of what is written in the Torah, they are forbidden to adopt a more severe attitude [than prescribed]. Therefore people traveling to Israel are forbidden to keep two festival days during their stay, even a provisory stay because the obligation to keep one festival day is dictated by the place where they are [Israel] and the rule about the severity of the place from where they came does not play in this case. And I wrote what seemed to me [correct]. Tsevi Askenazi s”t.

[40]

5. Critical Analysis of this Responsum.

The responsum is based on the following arguments:

n Generally we compare this problem with the rule of the minhagim. But praying the prayer of the festival cannot be considered as a severity with regard of the prayer of a weekday.

n Forbidding the performance of work during the second festival day is certainly a severity but the rule of the severity of the minhagim does not play in our case. Indeed if a foreigner settles in Israel he will be forbidden to observe to festival days because of the order of “bal tossif”. In such a situation we cannot oblige a traveler to keep two festival days.

[41] Thus in such a situation when the settler is forbidden to keep the second festival day, we cannot oblige the traveler to keep the second festival day and forbid him performing any work.

n The takana instituting the second festival day was introduced out of fear that the Jews of the foreign counties would lose the contact with Israel and would not keep the right festival day. Such a fear does not exist when these foreigners are on visit in Israel. The takana was not intended for them.

The responsum would perhaps have been more persuasive if it had been articulated as follows:

n From the motivation of the takana instituting the second festival day it appears that it was not addressed to the foreigners during their provisory stay in Israel because at this particular moment they could have no doubt about the Jewish calendar.

[42]n We must still examine the problem at the light of the rules of the priority of the minhagim. But the rule of the priority of the minhagim does not play in our case. Indeed if a foreigner settles in Israel he will be forbidden to observe to festival days because of the order of “bal tossif”. In such a situation we cannot oblige the traveler to keep two festival days.

n Even if one does not accept this reasoning we must still observe that as for the positive obligations of the second festival day (prayer, benedictions and Thorah reading) we cannot consider them as more severe customs.

n I would even add the following point. Yom Tov Sheni includes three points: first the positive obligations of the festival second the interdiction of performing work and third the suppression of the obligation of wearing tefilin.

[43] But as soon as we are outside of the takana there is an obligation of tefilin and the rule of the priority of the minhagim must at least abide by this obligation.

6. The refutation of this Responsum by R’ Jacob Emden.

It is generally accepted that R’ Jacob Emden, the son of Hakham Tsevi refuted his father’s argumentation in responsa She’elat Yabets I, no. 168. The supporters of the first opinion have generally used the argument of the refutation of Hakham Tsevi by his son in order to eliminate the second opinion.

[44] Let us examine this refutation and its main arguments.

n R’ Jacob Emden follows the theory of Rambam Hilkhot Kiddush ha-Hodesh III according which we keep today one festival day only in the places where we know that the messengers arrived and the people kept one festival day at the time of the calendar of observation. Therefore one must keep two festival days in all the new places. Therefore he argues, there is no interdiction, in principle, to keep two festival days in Israel.

n R’ Jacob Emden seems to understand Rambam, Hilkhot Yom Tov VIII: 20 according to the understanding of Maggid Mishneh that the traveler, even when he settles in a new place, must go on keeping the customs of his former place. Therefore he thinks that the Jews settling in Israel must go on keeping discreetly two festival days.

n R’ Jacob Emden ascertains that when there are two communities in a town with different customs or ruling there is no danger of dispute and of separation.

[45] Therefore, he says, as soon as the number of foreigners, settling in Israel, is sufficient to have an independent quorum, they are allowed to celebrate publicly the second festival day. They should go on and keep the two festival days publicly.

n The message and order instituting the second festival day because of the fear of unfair laws against the Jews and the fear that they forget the Torah was not sent only to the Diaspora but it concerned also the inhabitants of Israel. Today there is no difference between Israel and the Diaspora; they know all the fixing of the month. The reason of the institution of the second festival day applies to all the Jews without distinction. If he did not fear [to introduce new habits] he would say that all the inhabitants of Israel must keep two festival days.

It appears that the responsum is based on very problematic early beginnings; first that one keeps two festival days in Israel in places which did not exist during the time of the Mishna and the Talmud (third century) and had not a Jewish population, second that one beholds always, after settling in a new place, the customs of the former place. These two principles are not accepted by the halakha. Further he ascertains that communities can go on and keep two festival days and former customs officially after settling in Israel.

This responsum accounts for the exalted and exaggerated positions adopted sometimes by R’ Jacob Emden. In any case it cannot be considered as a serious refutation of his father responsum. On the contrary this responsum is a model of logic, rigor, concision and originality.

7. Other authorities supporting the second opinion.

Only a little number of authorities supported the opinion of Hakham Tsevi. However, as we established above, Hakham Tsevi was probably preceded by R’ Hananel and Ravan who championed the opinion that foreigners visiting in Israel, keep only one day. Among these other authorities we can distinguish R’ Saul Nathansohn who adopted a similar position, at least in theory (Sho’el u Meshiv, 3rd edition no. 28). R’ Shneur Zalman of Liady in Shulhan Arukh ha-Rav ruled also that foreigners, on a visit to Israel, keep only one festival day.

[46] He notes however that there are opponents.

[47]We must further notice that the problem of the foreigners visiting Israel was apparently not raised nor in the Talmud nor in the Rishonim. This could be considered as an indication that their status does not pose a problem and is identical with that of the Israelis. A similar consideration could be expressed about R’ Joseph Karo who did not raise the issue in Shulkhan Arukh. However he had raised the issue and followed the opinion 1 in his responsa Avkat Rokhel 26 and one should admit that he changed his mind.

[48] When going from the Diaspora to Israel, the obligation of Yom Tov Sheni would be a territorial obligation and not a personal obligation.

[49]C. Foreigners traveling in Israel do not keep two festival days, they wear tefilin on the second day but they do not perform work on this day.

[50]This position was adopted by R’ Shmuel Salant, longtime chief rabbi of Jerusalem during the second part of the nineteenth-century. R’ Yehiel Mihel Tikochinsky, his pupil wrote in his book Ir ha-Kodesh ve ha Miqdash that R’ Salant was inclined to rule according to the ruling of Hakham Tsevi. R’ Salant considered as certain that during the period of the empirical calendar by vision and messengers, when they kept the second festival day out of doubt, foreigners on visit in Palestine had no doubt and kept only one festival day. Therefore, he argued, today the rule cannot be more severe than at that epoch. As he dared not ruling as Hakham Tsevi because his teacher R’ Israel of Shklov had ruled according to the opinion 1 (Pe’at ha-Shulkhan, Hilkhot Erets Israel, chap 2, $ 15), he adopted an intermediate position considering the most severe aspects of both opinions. Therefore he advised not to keep the second festival day and to wear tefilin but to refrain on the second festival day from any work, normally forbidden on the second festival day.

The contemporary posek R’ Nahum Eliezer Rabinovitch of Maale Adumim has a similar position and he considers that one must behave according to the ruling of R’ Shmuel Salant. R. Rabinovitch finds in the text of Maimonides an allusion to the status of the foreigner visiting in Israel and the Israeli visiting abroad. The Israelis keep two festival days even when they travel abroad and the foreigners keep only one festival day when they are in Israel (Yad Peshutah, Hilkhot Talmud Torah VI: 14, 11, p. 477-478).

In Yabia Omer VI: 40, R. Ovadiah Yosef mentions that R’ Abraham Isaac Kook ruled that one should adopt the severe points of the responsum of Hakham Tsevi, thus to behave like the severe aspects of both opinions.

It is interesting to note that the problem is still with us and new responsa are still written on this issue. Even the champions of the majority opinion are sensitive to the new situations. In many instances, a specific element like the ownership of a house in Israel or the regular celebration of the three festivals in Israel or even the rental of an apartment in Israel on annual basis are generally considered by the champions of the opinion 1, as a sufficient element allowing keeping the festivals as the Israelis.

V. General conclusion.

The aim of the present article was analyzing the complex problem of the priority of the minhagim and explaining the evolution from the Talmudic references until the halakha in Shulkhan Arukh. Today the general problem has lost its acuteness and has more a historical interest. The difficulty of the problem results from the difficulty to understand clearly the Talmudic sources and their apparent contradictions. We have seen that these difficulties were at the origin of a great number of interpretations.

We examined also the problem of Yom Tov Sheni shel Galuyyot with respect to the travelers between Israel and the Diaspora and vice-versa. It appears that the case of the travelers from Israel to the Diaspora is examined in the Talmud; the traveler in his quality of Israeli is dispensed from keeping the second festival day and therefore his conduct during this day is determined by the rules of the priority of the minhagim, in the respect of the susceptibility of the local population. The converse situation, the case of the traveler from the Diaspora to Israel was not considered in the Talmud (this is at least the general understanding, but there are opposed opinions) and Shulhan Arukh did not raise the issue. Therefore there is much uncertainty in the treatment of the problem. The general opinion was to treat the problem on the same way as the symmetrical problem and to assimilate it to a problem of priority of minhagim. Others considered that we are out of the scope of application of this rule and there was never a problem at all so that the issue depends only on the localization of the traveler. A foreigner keeps two festival days abroad but only one day in Israel. The absence of true evidence leads to the rare situation that the three possible attitudes have their champions. We show that the majority opinion has also its weak points and the minority opinion is theoretically much stronger that one could imagine.