Hadaran: Who is going down to the pit of destruction?

Hadaran: Who is going down to the pit of destruction?

by Leor Jacobi

A siyum of a masechet of gemorah is truly a joyous occasion, usually the culmination of many weeks of rigorous group study; challenging, edifying, and uplifting. The centerpiece of the siyum is undoubtedly the customary recitation of the unique kaddish and special additional prayers framing the accomplishment as an integral link in the chain of dissemination of Torah – from the tannaim and amoraim whose divine words we ponder, to the great rishonim and ahronim who guide us in revealing their talmudic treasures and infusing them into the modern world.

Fortunate is our lot! Our gratitude is expressed in the prayer of Rabbi Nehunia Ben HaKana[1]:

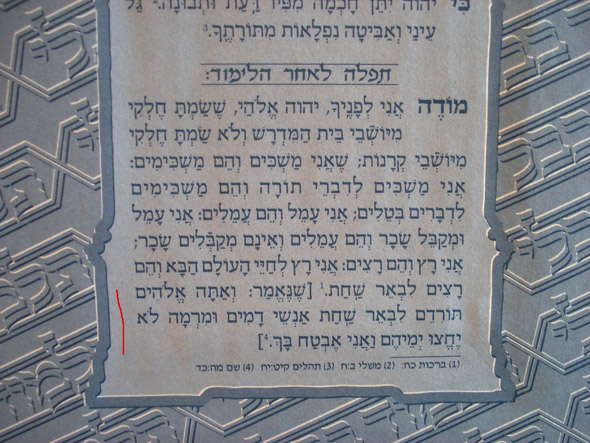

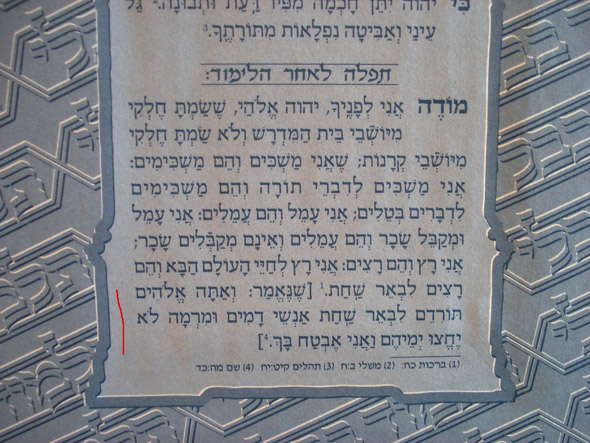

מודים אנחנו לפניך ה’ אלהי ששמת חלקינו מיושבי בית המדרש ולא שמת חלקינו מיושבי קרנות שאנו משכימים והם משכימים אנו משכימים לדברי תורה והם משכימים לדברים בטלים אנו עמלים והם עמלים אנו עמלים ומקבלים שכר והם עמלים ואינם מקבלים שכר אנו רצים והם רצים אנו רצים לחיי העולם הבא והם רצים לבאר שחת שנאמר וְאַתָּה אֱלֹהִים תּוֹרִדֵם לִבְאֵר שַׁחַת אַנְשֵׁי דָמִים וּמִרְמָה לֹא יֶחֱצוּ יְמֵיהֶם וַאֲנִי אֶבְטַח בָּךְ

Our exalted state can only be fully appreciated when contrasted with that of those not fortunate enough to join us in the beis hamidrash. The Yoshvei Kranos, identified by Rashi as idle shopkeepers who waste their time in frivolous conversation, are deprived of the rich rewards of Torah study, both in this world and in the next. They are to be pitied and even disdained for their boorish lack of concern for lofty matters.

The prayer proceeds a step further, however, in the concluding verse from Tehillim 55:24, cursing the ignorant with early death, destruction, and perhaps even damnation! And you, HaShem, lower them into the pit of destruction, murderous swindlers, may they not live out even half their expected lifespan. Are they really so wicked? At our joyous simcha, shouldn’t we rather be resolving to help inspire and mekarev these poor folk?

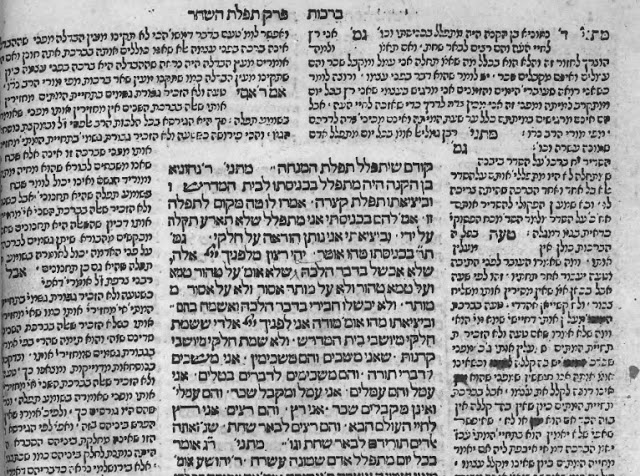

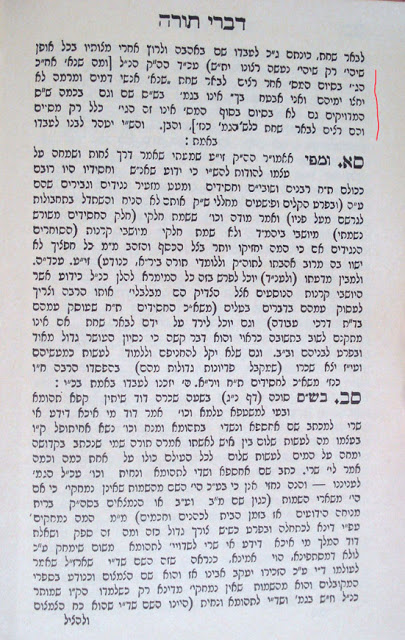

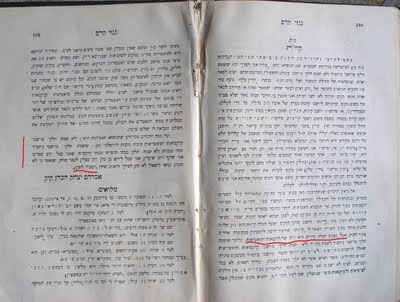

Did the creator of this prayer, Rabbi Nehunia Ben HaKana, or anyone from Hazal recite this verse? (If so, there would certainly be a a good reason for it.) A survey of the sources reveals a resounding: no. Not only does it not appear in Gemara Brachos 28b, but it does not appear in any of the known manuscripts, Rambam[2], or any of the many poskim rishonim that quote the prayer. Early versions of the Hadaran prayer do not include the verse either! See the attached photo of the early Venice and Soncino editions of the Talmud.[3] Nowhere. Gornisht.

In his Sefer Divrei Torah (Mahadura 5)the Munkasczer rebbe, an avid bibliophile, indicates that the verse should be omitted.

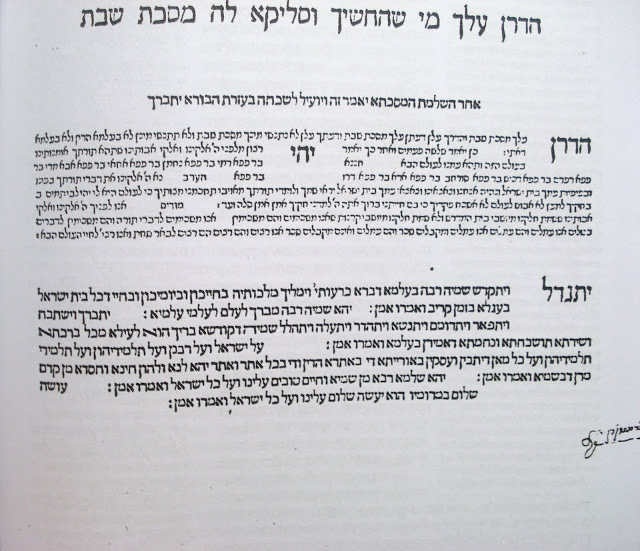

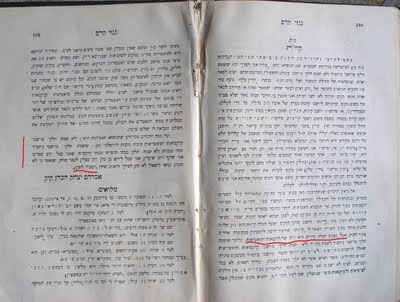

The verse only appears in one known halachic source: Halachot of Rif (Rabbi Yitzhak Alfasi). See below (1st edition, Constantinople 1509):

Why would Rif add this verse? He is usually involved with editing away verses from the Gemorrah, not adding them! Does it reflect an ancient custom of his? Why didn’t any of the great Rishonim who studied Rif cite this verse?[4] Ra’ah in his commentary on Rif quotes the entire prayer without mentioning the verse! None of the many known manuscript versions of Rif mention the verse![5] Its earliest known appearance in this prayer is in the first printed edition of Rif (published almost exactly 500 years ago, רס”ט, in Constantinople). Why did the publishers include the verse?

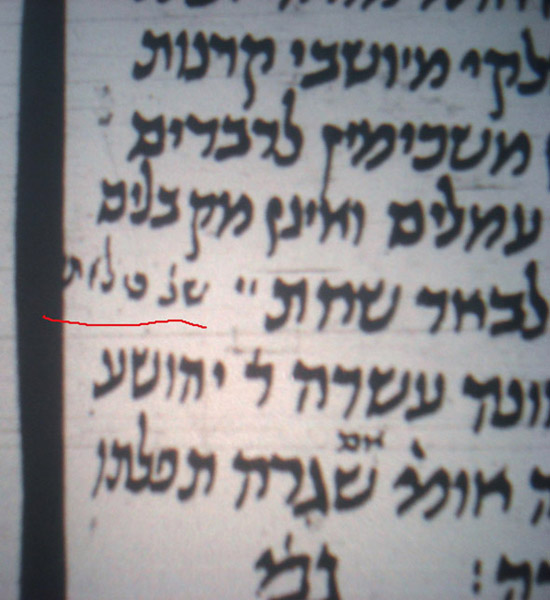

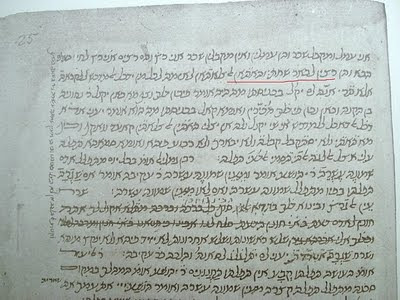

In the left hand side of the manuscript, one can see that a later scribe added a citation to a verse. Only a few letters are visible in the microfilm: שנ’ כי לא ת

This is clearly referring to a different verse! Without a doubt, it is the same verse cited at the end of the version of the prayer found in the Talmud Yerushalmi:

כִּי לֹא תַעֲזֹב נַפְשִׁי לִשְׁאוֹל לֹא תִתֵּן חֲסִידְךָ לִרְאוֹת שָׁחַת[7]

“For you will not abandon my soul to the grave, you will not allow your pious one to see (his) destruction.”

This verse is most fitting and proper here as a conclusion of the prayer. It lacks all of the problematic vitriol of the commonly found verse. This scribal addition undoubtedly represents an ancient custom[8], which the printers of Constantinople may have been unfamiliar with.[9] The verse they substituted, however, was certainly most familiar to them in a different context:

משנה מסכת אבות פרק ה

אבל תלמידיו של בלעם הרשע יורשין גיהנם ויורדין לבאר שחת שנאמר (תהלים נ”ה) ואתה אלהים תורידם לבאר שחת אנשי דמים ומרמה לא יחצו ימיהם ואני אבטח בך:

The students of Bilaam are certainly deserving of such a curse, for they are involved in sorcery, treachery, and other wickedness – if only they would be idle as the shopkeepers, that would be a tremendous improvement!

The custom of reciting Pirkei Avos on Shabbos afternoon dates back to time immemorial, and as a result of the regular study, many have mastered its teachings literally by heart. It doesn’t seem at all far-fetched to assume that the printing of this verse in Rif was a simple oversight. Eventually the verse entered into the hadaran prayer as we know it.

The prayer of Nehunia Ben HaKana is also found in many printed prayer-books in its original form, to be recited upon leaving the Beis HaMidrash. It is usually located just after shaharith.[10] Many of these contain the verse, such as the prayerbook printed by Rav Ya’akov Emden on his private press[11]. But many do not contain the verse.[12]

Rambam ruled that upon entering and exiting it is obligatory to recite the prayer of Nehunia Ben HaKana[13]. The Shulhan Aruch also follows his psak. In order to further facilitate the fulfilment of this duty, printers have recently begun printing the prayer in the inside front covers of their gemorrahs and mishnayos, including the verse. The editors of Artscroll are the most democratically accommodating – they include the verse in parenthesis. You can decide whether to say say it or not.

It’s well worth noting that a precedent to this custom of the printers is found in the Pesicha to the famous Tosafos Yom Tov commentary on the mishna by Rav Yom Tov Lipman Heller. He writes that since the recitation of these prayers is obligatory, and since many are unfamiliar with them, as they do not appear in the siddur (of his time), that he is printing them, according to the nusach of the RIF. And his nusach follows the printed version of RIF. He does not explain why he chose the RIF’s version over that of the Talmud, but it seems clear that he did not have access to manuscripts of RIF, and, unfortunately, relied on corrupted printed versions. It’s also unclear as to whether his concerns for proper nusach were with the concluding prayer at all, or with the prayer recited upon entering the House of Study, whose wording is much more varied between different manuscripts and printed versions. It could be that this “endorsement” of the Tosafos Yom Tov to the printed version of RIF contributed to the eventual inclusion of the verse in later printings of the Hadaran prayer at the end of tractates and later, in prayer-books.

Hopefully, our good friends, the “yoshvei kranos” will be taking part in a daf yomi shiur and joining us at the next siyum, reciting the Hadaran along with us, and meriting Olam HaBa!

Appendix

Theaters and circuses, the Talmud Yerushalmi (and Rav Kook)

(By a happy coincidence, David Segal recently posted at the Seforim Blog on this very topic!)

We are not the first ones to find the prayer in the hadaran to be overly contentious. No less an illuminary than Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook, OBM, the first chief Rabbi of Israel, was deeply disturbed by this prayer’s tone. Yoshvei Kranos are today’s ba’alei batim. They keep mitzvos and give tsdakah. The takanah to read the torah on Monday and Thursday is for them, so they should not go too long without hearing words of torah. It goes completely against the grain of Hazal to curse them! In fact, even without the verse, why should they be punished at all?

We are not the first ones to find the prayer in the hadaran to be overly contentious. No less an illuminary than Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook, OBM, the first chief Rabbi of Israel, was deeply disturbed by this prayer’s tone. Yoshvei Kranos are today’s ba’alei batim. They keep mitzvos and give tsdakah. The takanah to read the torah on Monday and Thursday is for them, so they should not go too long without hearing words of torah. It goes completely against the grain of Hazal to curse them! In fact, even without the verse, why should they be punished at all?

Rav Kook proposed a truly fantastic solution. A corruption occurred in the text: the yoshvei קרנות of the Talnud Bavli are really yoshvei קרו”ת, roshei teivos for קרקסיות andתרטיות , those who patron theaters and circuses, which in fact, is the exact nusach of the version of the prayer found in the baraisa of the Talmud Yerushalmi!

What exactly goes on in these theaters and circuses? The gemarah in Avodah Zara 18b states that they are essentially a moshav leitzim, foolish and irreverent. Another opinion cited there is that these were much more nefarious centers of Avodah Zara and Shfichus Damim, gladiator sports, public executions and like. Historically, both of these opinions seem correct – theaters and circuses where occasionally more pernicious activities took place. All in all, they don’t seem to be much too different than the modern versions of popular “entertainment”[14].

The curse of Rav Nehunia’s prayer is directed against these insidious people who waste away their free time in such sordid foreign entertainments, as opposed to the Torah-true who spend their free time immersed in learning in the beis hamidrash or in prayer in the beis kneses, even if during the work-day they are but simple “idle” shopkeepers. In this context, even the dubious additional verse is somewhat appropriate[15].

Rav Kook went so far as to call for “correcting” the nusach of the prayer and adopting the version of the Talmud Yerushalmi! That proposition certainly has merit, but is it really the true intention of the Talmud Bavli itself?[16] Perhaps this is not the only suggestion of his that, in retrospect, seems a bit far-fetched.[17] However, it seems that his insight into the tradition of the Talmud Yerushalmi and its stark opposition to “theaters and circuses” teaches a lesson which is especially pertinent today, and can deepen our appreciation of the importance of this truly enigmatic prayer.

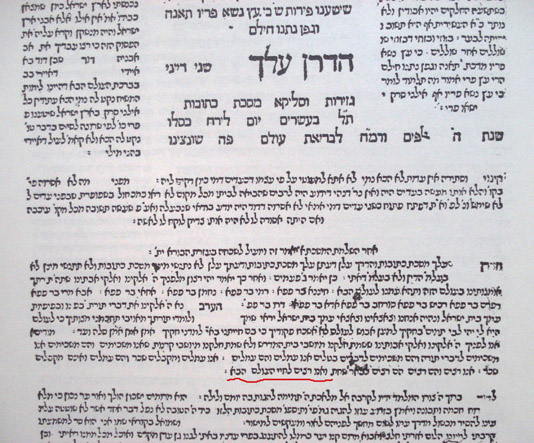

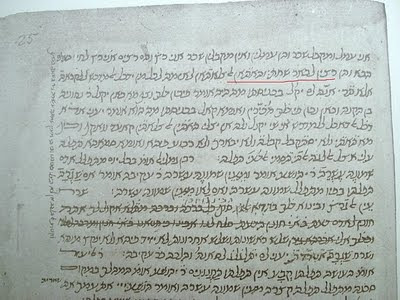

Here are Rav Kook’s words (you may click this image to read a larger copy):

Here are Rav Kook’s words (you may click this image to read a larger copy):

The original version of the prayer appears to be found in the Talmud Yerushalmi, produced under the glare of Greco-Roman culture with its ubiquitous theaters and circuses. In Sasanian Babylon, these cultural expressions were unheard of, hence they were restated as the more familiar yoshvei kranos. In contrast, our modern secular culture of entertainment is, for the most part, a western one, and hence the version of the Talmud Yerushalmi takes on crucial added significance today.

Many thanks to Moshe Bloi, Ezra Chwat and Shamma Friedman. All errors are, of course, mine.

Many thanks to Moshe Bloi, Ezra Chwat and Shamma Friedman. All errors are, of course, mine.

Note: This article is based on one which originally ran in Kolmos of Mishpacha magazine and they take no responsibility for the content here. You can read the original article here.

UPDATE 8/18/2011: A song has recently been composed as a result of this article and discussions surrounding it’s Hebrew and English versions. The song lyrics consist of only the two verses and highlights the contrast between them musically.

Here the composer explains the composition in Hebrew and provides a link to the previous Hebrew discussion which inspired it:

[1] Brachos 28b. The Hadaran prayer has been adapted to the inclusive plural form, מודים אנו, rather than the original singular מודה אני

[2] See attached photo of the Tefillah in Commentary on the Mishna, that Rambam himself copied by his own hand!

[3] Note that the order in the prayer is switched around, probably in order to end on an upbeat, good note.

[4] In the back of the new Oz V’Hadar gemarras, the Magid Ta’alumos is cited, who explains that the verse is included in order to end the prayer on a positive note (!), v’ani evtah boch, insead of be’er shachas. The same explanation is offered by the Dinover rebbe, the the author of the classic Bnei Yesoschar, in his Maggid Ta’alumah (פרעמישלא תרל”ו) in his commentary v’Heye Bracha, referring to the inclusion of the verse by the Tosafot Yom Tov in the introduction to his monumental commentary on the Mishna. He makes no reference to the Rif. Perhaps he thought that the verse was added to the Rif according to the Tosafos Yom Tov? It’s worth noting that both the Maggid Ta’alumos and the Maggid Ta’alumah have the same observation on the inclusion of this verse, independently!

[5] Thanks to Dr. Ezra Chwat, of the Israel National Library Manuscript Department, who is preparing a new critical edition of Rif (scheduled to be used in the upcoming edition of Shas Lublin), for allowing me to utilize his forthcoming work. Further, he guided me to four additional “less reliable” manuscripts which are not utilized centrally in preparing his new edition. None of them contain the verse either.

[6] Oxford Huntington 135:

[7] תהלים פרק טז, י

[8] A fascinating new Teshuva by Rav Yitzhak Ratsaby of Benei Brak has been published (Ma’ayan Nissan 5770) on the exact question addressed in this article, the inclusion of the concluding verse in the prayer of Rav Nehunia ben Hakana (link). There, Rav Ratsaby cites Yemenite prayer-books and Teshuvot which demonstrate that the custom of reciting the verse from the Talmud Yerushalmi (like the scribe of the RIF manuscript) continued among certain Yemenite kehillot until almost the present day. Unfortunately, Rav Ratsaby did not check manuscript versions of RIF, and thus understands that the talmud of the RIF himself contained the problematic verse, leading him to propose far-fetched justifications for the custom. Here is my response (Ma’ayan Tammuz 5770).

[9] Although it seems quite doubtful that the printers had this exact manuscript in front of them, it seems likely that they had a similar manuscript. Dr. Ezra Chwat doubts that the Oxford Huntington manuscript was used by the printers as there are many discrepancies between it and the printed version of Rif. It serves as the primary manuscript for Dr. Chwat’s new edition of RIF. According to Dr. Chwat, the manuscripts can be used to resolve many seeming contradictions between RIF and RAMBAM!

[10] So that one may go מחיל אל חיל, from the beis hakneses to the beis hamidrash.

[11] Rav Yitzhak Ratsaby, in his recent tshuva (see note above) argues that the custom in Rav Emden’s siddur was only to recite part of the verse, but it seems more likely that this was simply a printer’s abbreviation. The reliability of the wordings found in this siddur are quite questionable, based on Rav Ya’akov Emden’s own testimony in the introduction that many texts were simply copied from other prayer-books.

[12] Among current prayer-books: the accurate Tefillas Yosef and Ezor Eliahu do not include the verse. Siddur Vilna, on the other hand, does contain the verse.

[13] Commentary on the Mishna. See Levush and Aroch HaShulhan (Orach Haim 110) for explanations as to why many do not recite the prayers.

[14] Internet anyone?

[15] This fact was noted independently in the recent Responsa of Rav Yitzhak Ratsaby, Ma’ayan Nisan 5770

[16] The Aderes in Tefilas Dovid, p.12, states that yoshvei kranos are also engaged in nefarious activities, as seen in the Talmud Yerushalmi. He claims that yoshvei kranos here doesn’t follow its normal meaning, going against Rashi. Rav Kook was the Aderes’ son-in-law so its not surprising that they both have the same approach in understanding the Bavli according the the Yerushalmi. Rav Kook probably favored Rashi’s interpretation of yoshvei kranos, and hence, was forced to actually alter the text of the Bavli.

[17] Rav Kasher, in Torah Shleima, Vol 15 page 140, dismisses Rav Kook’s theory entirely, claiming that the version of the Talmud Bavli is the original one! His proof is the fact that a parallel to the bavli appears in Pirkei Avot d’Rebi Nathan A. However, that collection is widely recognized to post-date the Bavli itself, which it widely quotes from.