Eliyahu Bachur in Isny

ELIYAHU BACHUR (1469 – 1549) IN ISNY

by: Dan Yardeni

Dan Yardeni, an engineer by profession (Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, 1963), is entrepreneur specializing in cutting edge materials and materials production processes.

As sideline, he researches problems in the history of Hebrew books printing and printers. He also contributes articles to the Culture and Literature sections of Haaretz and other Israeli newspapers. This is his first post at the Seforim blog.

A little street in Tel Aviv commemorates the personality of a colorful Jewish culture hero at the time of the Italian Renaissance, known as Eliah Levita by Christians and Eliyahu Bachur by Jews. While he considered himself primarily a linguist, he was also a teacher, translator, writer and editor, debater, poet, singer and humanist with a deep sense of social awareness, which he expressed in sharply worded satires. While all his life he was an observant Jew, he was also a close friend and teacher of the greatest Christian scholars of his day and became a foremost “cultural agent” between Judaism and Christianity.

Eliahu Bachur’s unusual name is due to the fact that he remained a bachelor for a long time, and later adopted the epithet in the sense of Bachur – Chosen (see his preface to Sefer HaBachur, Isny 1542 where he explains the name of the book and comments: “…. היות שם כינויי משונה ובשם בחור מכונה …. ” ). He was born in southern Germany in 1469 and died and was buried in Venice at the age of 81, a rather advanced age at the time.

Most of his life he lived and worked in Italy. For a brief period of two and a half years, between 1540 and 1542, Eliyahu Bachur moved to the small town of Isny in the picturesque Allgäu region of southern Germany. Isny was at that time a a free self-governing city organized as a republic within the Holy Roman Empire, then under the rule of Charles V. Eliyahu Bachur was invited by the Christian reformer and Hebraist Paulus Fagius to work with him as editor and proofreader in the printing-house, which Fagius had founded in Isny. Despite the burden of his seventy-one years, Eliyahu accepted the invitation, left his home in Venice and crossed the Alps to live in that little town. Why did he do it? The large and world famous printing-house of Daniel Bomberg in Venice, where he had worked as an editor and proofreader for many years, ceased operating at that time and Fagius was offering him a good job and, most important, undertook to print the books Eliyahu had written.

Eliyahu Bachur describes his journey to Isny at the end of his book ‘Tishbi,’ the first of his books to be published in the new printing-house. (The name of the book alludes to his name, Eliyahu). The book, printed in typical Ashkenazi Hebrew typography, constitutes a kind of dictionary describing 712 roots of Hebrew words. And so he writes in the preface to the book: “… I beg anyone, scholar or student who reads this book and finds a mistake or error, to note that it is the fruit of haste since I was in a hurry to reach this place and when I left my house the book was not yet finished, and as I was en route, crossing lands of raining hills and mountains I stood trembling, weighing matters up in my mind and writing them in my heart, and then, when I reached the inn, I opened my case, took out my notebook and wrote down the things which the Lord had put into my heart.”

We know of sixteen titles (sometimes in 2 editions, with and without Latin translation), which Eliyahu Bachur published in Isny. He may have printed more, of which no copies survived. Most of the time he was the only Jew in that Christian town which was so devoutly Protestant that it did not allow Catholic Christians to reside within its walls. The contents of his books, and the texts which he wrote and appended to them, are of great interest still today. Most touching is the reflected conflict between his desire to publish the books he had written and the longing for his family and for Venice, the town where he had lived most of his life.

While being a deeply religious and observant Jew, Eliyahu Bachur displayed cultural openness to the Christian world. He did this in spite of the fierce opposition of rabbis, who regarded him with suspicion, as someone who was prepared to venture beyond the self-imposed barriers surrounding the Jewish scholarly community (See his preface to Masoret Ha-Massoret book printed in Venice 1938 and later). He also had the courage and intellectual honesty to admit that he had been helped in translating difficult Greek words to Hebrew by the learned Christian cardinal Egidio Viterbo, to whom he had taught Hebrew during his sojourn in Rome years earlier. He dared to state, in face of virulent opposition from leading orthodox rabbis, that the punctuation of the Hebrew language was a later invention and not as ancient as had been thought until then. In his rhyming introduction to his book ‘Tishbi,’ he challenged those who disagreed with him to react still in his lifetime:

“….. / כי אומנם לא שקר מילי / אם לא איפא מי יכזיבני / מה שגיתי יבין אותי / יכתוב לו ספר איש ריבי / אך יעשה זאת טרם אמות / כי מה אשיב אחרי שכבי / או ימות גם הוא כמוני / או ימתין לי עד שובי / …….”

“…Indeed my words are not a lie / So who will dispute me? / If I erred, please show me where / And my rival may write his own opinion / But let him do it before I die / Because once I died how could I reply? / Or possibly he too may meanwhile pass away / Or he might have to wait for my resurrection from the dead….”

Later, in a playful rhymed foreword, combining genuine modesty with an awareness of his own value, he added a well-known fable attributed to Pliny the Elder, which Eliyahu claims to remember from his youth:

“אפתחה במשל פי / אשר שמעתי בימי חרפי / כי היה באחד המקומות / אשר נקבו בשמות / אמן אחד צייר / וצייר צלם איש על נייר / והיה האיש ההוא / תם וישר / יפה תואר ומשוח בששר / וידביקהו על לוח עץ / ועל פתח ביתו היה אותו נועץ / להראות העמים והשרים את יופיו / כי כליל הוא מהדרו וצבי עדיו / ויהי כאשר כל העם רואים / והנה בתוך הבאים / זקן אחד רצען / על משענתו נשען / וראה והביט גם הוא / אחרי כן פתח את פיהו / ויאמר הנני עומד משתאה / איך הצייר שגה ברואה / הלא תראו כי שרוך הנעל / הפוך למטה למעל / וכשמוע הצייר את זאת / יצא גם הוא לראות / וירא ויניע ראש / והודה ולא בוש / ויאמר צדקת אתה הזקן / אך הלילה המעוות אתקן / וכן תקנהו טרם הלך לישון / ולמחרתו הוציאו כמשפט הראשון / ויבוא הרצען שנית / ויוסף להביט בתבנית / ויאמר לצייר יפה תיקנת ועשית / אבל בדבר אחד שגית / כי רואה אני דבר נבזה / כי הברכיים אינם דומים זה לזה / האחד גדול והאחד קטן / ויאמר לו הצייר לך אל השטן / כי משרוך הנעל ולמעלה/ אין לך בחכמה חלק ונחלה / ויהי הרצען לבושה ולכלימה / ויפן וילך בחימה / וכן יראתי גם אני / שכמקרה הרצען יקרני / בעניין זה החיבור / רעה עלי ידובר / ויאמר אלי מי שהוא / מה לך פה אליהו / כלך למדברך אצל דקדוק ומסורות / אין לך עסק בנסתרות / אל תחמוד כבוד יותר מלימודך / ואל תנבל כסא כבודך / ולכן יראתי לקרב אל המלאכה / פן לא אראה בה סימן ברכה / אך רוחי הציקתני / ואש עצור בעצמותי ושרפתני / וכלכל לא יכולתי / ומאת השם עזר שאלתי / יצרף לי למעשה המחשבה / ויורני בדרך הטובה / כי מכיר אני את מקומי / שיותר מידי נטלתי גדולה לעצמי / שמלאני לבי לפרש כל השורשים / אשר בשום מקום אינם מפורשים / ואף מאותם המפורשים כבר / אחדש בכל אחד איזה דבר / ורובם מן הגמרא ומדברי רבותינו / כגון בראשית רבא ותנחומא וילמדנו / ואף שבעוונותיי / כבר עברו רוב שנותיי / ולא ראיתי בטובה / בהוויות אביי ורבא / ולחכמים מעט שימשתי / ומשאם ומתנם לא בשתי ביקשתי / מכל מקום לבי לא מנעני / ובאגדות ובמדרשים יגעתי / להוציא מהם דברים חשוקים / ובפרושי ומדרשי הפסוקים / עד שרוב גירסתם היא לי ידועה / וזה יהיה לי לישועה / את הספר הזה לחבר / ולברר וללבן את אשר אדבר / …………/.

The fable tells the story of the famous Greek painter Apelles (a contemporary of Alexander the Great), and a cobbler,. Apelles drew a beautiful young man and pasted the painting on wooden board that he placed at his doorway to impress all passers–by. Among them was an old cobbler, leaning on his cane. The cobbler gazed at the painting and commented: “I am surprised how the artist made such a mistake. You see, the shoelace goes upside down”. When the artist heard that, he went out to see, nodded his head and consented: “You are right, old man. But tonight I shall correct the mistake”. And so he did before going to sleep and the next day he hung the painting in place as before. And the old cobbler came again. He looked at the painting and told the artist: “Well done but there is still another mistake: the knees are not alike, one is bigger than the other”. The artist said then commented angrily: “Go to hell. From the shoelace upwards you know nothing”. The cobbler was ridiculed by all around and turned away in a rage. And, says Eliahu Bachur, he is afraid that the same will happen to him with this book, the “Tishbi”. Somebody will say: “What are you doing here? Go back to Hebrew grammar and Massoret. Don’t deal in what you don’t know and don’t ask to be honored in doing so“. Therefore, he was afraid to undertake that work, in which he might fail. However, he could not restrain himself and asked God for help in showing him the right way. Eliyahu adds that he knows his place and that he may be presumptuous in daring to explain all the Hebrew roots, which are not explained elsewhere, adding that even to those that had been explained, he was still bringing something new from the Gmara and other sources.

Particularly impressive is the friendship and mutual respect that developed between the old Jew and the Christian preacher Paulus Fagius in the course of their work together in Isny, about which Eliyahu writes in the foreword to the book:

“……..ובבואי הנה תהיתי בקנקנו ומצאתיו מלא ישן ולא הוגד לי החצי מחכמתו וידיעתו, ורבים שואבים מי תורתו, ודורש טוב לעמו, נאה דורש ונאה מפרש ………..ובראותו הספר הזה אשר חיברתי והכיר רוב טובו ותועלתו, נזדרז מאד והעתיק אותו ללשון לאטין אשר קראו קדמונינו לשון רומי וחיבר שתי הלשונות יחד ונשים עיוננו עליו בכל מאמצי כוחנו, הוא מצד אחד ואני מצד אחר. ונקרא איש אל אלוהיו שיצליח את מלאכתנו ………”

“…And when I came hither I wondered about his character, and I found him full of wisdom, and I had not been informed about the breadth of his knowledge, and many come to learn from him, and he performs good deeds, in sickness and in health… And when he saw the book which I had written he recognized its worth, and hastened to translate it into Latin, which was the language of ancient Rome, and together we made connections between the two languages, he on the one hand and I on the other, and each one of us sought guidance and help from his God.” (my emphasis, D.Y.)

Being a devoted Christian Pastor, Fagius didn’t abandon his missionary vision and one of the books he printed in Isny, ‘The Book of Belief’ (Sefer Amana), is unmistakably a missionary tract. The book was published in two versions, Hebrew and Latin. In the introduction to the Hebrew edition Paulus Fagius wrote in Hebrew: “The Book of Belief is a goodly and pleasant book which was written by a wise Israelite a few years ago in order to teach and prove quite clearly that the belief of Messianic in the Lord the father, his son, and the holy spirit, and other things is entire, correct and without doubt…”. We can only imagine how uncomfortable Eliahu Bachur felt in proofreading this book.

Now, as was customary in those days when printers took pride in their work, Paulus Fagius placed a colophon at the end of the books he printed with his printer’s emblem, an elaborate and beautiful woodcut of a tree surrounded by verses, which he regarded as his motto in life. Among them was one verse, which appeared with slight variations in most of the books that were printed at Isny:“תקוותי במשיח הנשלח שהוא עתיד לדון חיים ומתים“ “My hope is in the Messiah who was sent (נשלח) and who will judge the living and dead.”

As stated, ‘The Book of Belief’ appeared in Hebrew, apparently intended for the Jews, and in Latin for the Christians. The Latin version ends with the verse cited above, while at the end of the Hebrew version the printer’s emblem appears with a slight difference, which is not immediately discernible:

תקוותי במשיח הנשלך אשר הוא יבוא לדון את חיים ומתים

My hope is in the Messiah who was dismissed (הנשלך) and who will come to judge the living and dead.

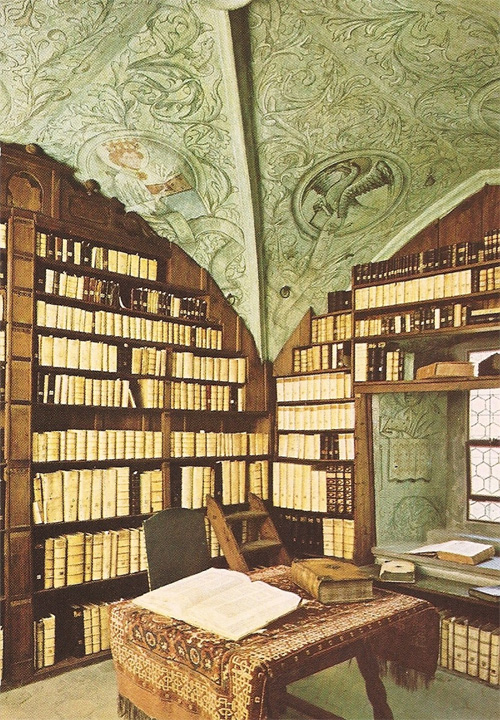

There can be no doubt that this is no printer’s error but a subtle message sent by Eliyahu Bachur in his capacity as the book’s proofreader to his Jewish brethren down the ages, saying: “I have not betrayed. You know what I think about this”. I noticed this subtle difference when I examined the books, which are kept in the amazingly well preserved study of Paulus Fagius next to the Church of Saint Nicholas in Isny, where he preached nearly 500 years ago. When I brought it to the attention of the extremely kind priest who escorted me and who now occupies Fagius’s chair, he was very surprised and, I fear, somewhat offended.

Eliyahu Bachur was attuned to the need to disseminate knowledge not only to the educated Jewish elite but also to the general Jewish community, men and women. Therefore, another book, which Eliyahu Bachur printed in Isny in the year 1541, was ‘Bovo d’Antona’, a popular adventure novel about knights, which he translated into the Judeo-German dialect, Ivri Teitsch (western Yiddish From the introduction he wrote to the book, we learn about the status of women in Jewish society at that time and about their reading habits. In rhymed introduction, he tells all righteous women“איך אליה לוי דער שרייבר, דינר אלר ורומן וויבר” that there are women who complain that he does not print for them in Ivri Teitsch the books that he has written, and they are right. And since he has written eight or nine books in Hebrew and since he is now rather old, he wishes to publish all these books and poetry in Ivri-Teitsch. The first of which will be the “Bovo Buch,” which he translated from Italian thirty-four years earlier. Since this translation contains words in Italian, he will print a glossary at the end of the book explaining their meaning [and so he did, D.Y.]. Naturally he cannot transmit,the melody by which the book should be read. “איך זינג עש מיט איינם ועלשן גיזנק, קאן ער דרויף מכן איין ביסרן, זא הב ער דאנק” . He himself sings it in the Italian melody but everyone can adapt a better melody to the text, as he wishes. At the end of the book, Eliyahu Bachur adds that he hopes to print more books in Ivri Teitsch, but apparently he did not, or perhaps no copy has reached us. Of the ‘Bovo d’Antona’ book, only a single copy (Unicum) survives, which is preserved in the Zurich Public Library. However, the book was so popular at the time that its name has given rise to the expression that we use still today, “Bobe Meise” in the sense of silly, nonsense tale.

The book ‘Meturgaman’, (“Translator”), which Eliyahu Bachur composed and printed in Isny in 1542, was intended to be a dictionary which “Will explain all words, difficult and easy alike, which appear in the Aramaic translations of the bible and Talmud Yerushalmi”. To the book Eliyahu Bachur added a colophon, which sheds light on a touching side of his personality. In the colophon Eliyahu printed a delicate and sweet love song to his wife whom he had left behind in Venice:

“והנה מאחר שקפצה עלי הזיקנה / ואני איש זקן וכבד מאד / ומידי יום יום תכהה עיני ונס ליחי / אשוב מצבא העבודה ולא אעבוד עוד / ואלך לי אל ארצי אשר יצאתי משם / היא מדינת וונציה/ ואמות בעירי עם אשתי הזקנה / ולא אניד עוד רגל ממנה / והיא תשת עלי עינה / ורק המוות יפריד ביני ובינה/ ואשב שם כל ימי חיותי/ ואשלים חיבור הספרים אשר החילותי/ אז אומר לאל אשר יצר אותי/ קח נא את חיי כי טוב מותי”.

The song is translated here without modifications or explanations, though the charming wording in Hebrew is lost:

“And since I became old and heavy, and each day my eye sight weakens and my strength is leaving me, I shall retire from work and go back to the homeland that I left, the land of Venice, and die there with my old wife, and I shall never move again from her, and she will keep an eye on me and only death shall part us, and I shall live there the rest of my life and complete the books which I have already started to write. Then I shall ask the Lord who created me: take my life, it is better that I die”.

And in another song below this one, the old scholar summarize his life and work in most touching words:

“הלל אל אל המלך נאמן אבינו האב הרחמן

שהחייני עד הגעתי עתה אל זה היום וזמן

היה איתי עד נטעתי זה הנטע נטע נעמן

בו נגלות כל המילות העבריות עם תרגומן

גם הוא מורה בגיליון איה תחנותן ומקומן

הוא כמליץ שהוא ממליץ ובטוב מילין הוא מטעימן

ויי שוכן שמים וממנו דבר לא נטמן

ידע כי לא עשיתי זאת להיות נקרא רב או אמן

כי הנותן לכסיל כבוד כצרור אבן תוך ארגמן

לאל בלבד נאה כבוד ולזולתו הא ליכא מאן

הן לכבודו ולאהבתו בלבד רשמתי רישומן

אנא אלי לי ולאשתי החסד גם האמת מן

שהיא לא תהיה אלמנה ואני לא אהיה אלמן

יחד נמות ובגן עדנות תוך חיקה אישן עד לזמן

יבוא הקץ ואזי נקיץ ולחיי עד יחד נזדמן

ובכך תמו גם נשלמו דברי השירה עד תומן

ואני אליה המחבר לפרט זאת השנה סימן“

| Praise the God, faithful king |

Our merciful father

|

| That kept me alive | To this date and time |

| Be with me till I plant | This pleasant plant |

| In which all Hebrew words are revealed |

With their translation |

| And also indicate | Where they are located, |

| Explaining them |

In plain words. |

| God in heaven | From him nothing hides |

| He knows that I did not do that | To be called rabbi or scholar, |

| Because rendering honor to a fool | Is like wrapping stone in expensive textile |

| Only God deserves honor | Nobody else |

| And to his honor and love | I wrote what I wrote. |

| Please God, to me and my wife | bestow grace and truth |

| That she will not become a widow | And I shall not become a widower |

| Together we shall die and in Garden of Eden | In her bosom I shall sleep until |

| End of time and then we shall awake | And for ever be together |

| And here ended and completed | This song |

| I Eliyhau the writer |

In the year ….. |

Eliyahu Bachur’s wish was only partly fulfilled. He returned to Venice after the short-lived printing house in Isny closed down, and even though he edited and proofread a few more books for printers who replaced Bomberg’s enterprise, his strength continued to weaken. His long time co-worker in the printing business, Cornelio Adelkind in a letter to the humanist Andrea Masius in 1547 calls Eliyahu איש ערירי (Lonely man) which implies that his wife passed away few years before him. Eliyahu Bachur died in the month of Shevat in the year Shin Tet (1549) and was buried in the old Jewish cemetery in the isle of Lido near Venice. The headstone on his grave is still to be seen. I visited his grave, put a little stone on it and read the engraved epitaph, which includes sophisticated wording and allusions in Hebrew. This and the fact that the epitaph does not refer to the day of his death may suggest that he composed the text himself:

ש”ט לפ”ק

ר’ אליהו הלוי בחור ומדקדק

הלא אבן בקיר תזעק ותהמה לכל עובר

עלי זאת ה-קבורה

עלי רבן-אשר נלקח ועלה בשמיים

אלי-יה ב-סערה

הלא הוא זה אשר האיר בדקדוק אפלתו

ושם אותו לאורה

שנת שט שט בחדש שבט בסופו, ונפשו ב

בצרור חיים צרורה

It was impossible to translate the delicate playing in words that is concealed through the epitaph. The text below is only a shadow of its poetic brilliance.

Shin Tet le Prat Katan

Rabbi Eliyahu Halevi Bachur And Grammarian

A stone from wall will cry and moan to every passer by

On this grave

On rabbi Eliyahu who went to heaven

To God by a storm

He is the one who lightened the darkness of [Hebrew] grammar

And put it to light

Year Shin Tet at the end of the month of Shevat and his soul

In the bonds of life be bound

תנצב”ה