New Writings from R Kook and Assorted Comments, part 1

by Marc B. Shapiro

I now want to return to R. Kook and discuss some of his writings that have recently appeared. This is the first of what will be a five part post. It will be followed by at least one other multi-part post also dealing with R. Kook’s new writings.

For those who have never read R. Kook and don’t understand why there is such excitement every time a new collection is published, I suggest you do the following: Take one of the volumes and sit with it for an hour, just going through it, page after page. Odds are that you will be hooked. The originality that you find, and the power of his writing, is just breathtaking. It is impossible not to sense the power of his spirit, and it draws you in.

Books will be written on R. Kook, focusing on the insights found in the recently published volumes. They will analyze what is original in these works and the evolution of his thought. My purpose is more limited as I just want to call attention to some passages that caught my attention and which I think are significant, not just in the context of R. Kook’s writings, but also for anyone interested in Jewish thought.

In 2006 R Kook’s Kevatzim mi-Ketav Yad Kodsho appeared, and we can thank Boaz Ofen for this. Included in this volume is what is referred to as the last notebook from Bausk, which was where R. Kook served as rabbi from 1901 until his aliyah in 1904. On pp. 66-67 we find what I think is R. Kook’s first discussion of evolution. Unlike his other writings, here R. Kook mentions that he is relying on Maimonides on how to deal to deal with it. He mentions that Maimonides assumes the eternity of the world when he seeks to prove the existence, unity, and incorporeality of God. Maimonides adopts this model so that his proof will be acceptable to everyone. R. Kook states that this is also how we should deal with the issue of evolution. In other words, even if we don’t accept it, we should, for the sake of argument, assume that evolution is correct and explain the Torah based upon this. This will mean that even people who accept evolution will see the truth of Torah. By rejecting evolution, and declaring that it is in opposition to the Torah, right from the start you are stating that Judaism has no place for those people who accept one of the major conclusions of modern science. It is noteworthy that this text does not have any of R. Kook’s later thought, which speaks of the theory of evolution as being in accord with kabbalistic truth.

Another early statement of his with regard to evolution is found in Shemonah Kevatzim 1:594. Here he says that it is very praiseworthy to attempt to reconcile the Creation story with the latest scientific discoveries. He says that there is no objection to explaining the Creation, described as six days in the Bible, to mean a much longer period. He also states that we can speak of an era of millions of years from the creation of man until he came to the realization that he is separate from the animals. This in turn led to the beginning of family life, in other words, “civilization”.

What R. Kook is saying is that the entire story of the creation of Adam and Eve is not to be viewed as historical. Rather, it is a tale that puts in simple form a long development of man’s intellectual and spiritual nature.

[2] He doesn’t see this development as random, for he says that at the end of the long period it was a vision, or perhaps we should call it an epiphany, that offered man the perception that it was time to establish family life. It is, I think, obvious that the אדם referred to by R. Kook as beginning civilized life is not an actual historical man (i.e., Adam), but rather humanity as a whole.

[3]

אין מעצור לפרש פרשת אלה תולדות השמים והארץ, שהיא מקפלת בקרבה עולמים של שנות מליונים, עד שבא אדם לידי קצת הכרה שהוא נבדל כבר מכל בעלי החיים, ועל ידי איזה חזיון נדמה לו שצריך הוא לקבע חיי משפחה בקביעות ואצילות רוח.

R. Kook also explains that the deep sleep God placed Adam in (Gen. 2:21) can be understood as representing the length of time it took for humanity to come to the awareness of the idea of “bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh”. In other words, R. Kook sees the opening chapters of Genesis as representing a long period of development of the most important ideas of civilization, that of the dignity of man and the importance of family and the bond of marriage. Nothing here is as it appears, and literalism is out of the question.

We find in R. Kook’s most recently published book,

Li-Nevokhei ha-Dor, more passages that relate to what I have been discussing.

[4] This is an early work which was being prepared for publication and was released on the internet against the wishes of the editor. It has now been widely distributed and there is no reason not to cite it. R. Kook saw this book as a modern day

Guide for the Perplexed, so obviously there is a great deal we can learn from it. Shortly after the work was “released,” another edition of the book was published by the folks at Merkaz ha-Rav. They called it

Pinkesei ha-Re’iyah, vol. 2, and like everything else produced by these people, it is heavily censored.

[5] (Parts of

Pinkesei ha-Re’iyah have been included in the new

Humash ha-Re’iyah that was just published. Here is a sample.

Although it would have been better had the editors used

Li-Nevokhei ha-Dor, this new Humash is still a wonderful book to take to shul. You can find out more about it

here.)

Li-Nevokhei ha-Dor begins (ch. 2) by arguing that it is the “obligation of the true sages of the generation” to follow in the path of the medieval greats who were always concerned about those suffering religious confusion. While the contemporary spiritual leaders must respond to the concerns of modern Jews, R. Kook points out that since the issues confronting people today are so different than those of the medieval period, the works of the rishonim are of only limited value in confronting the current problems.

In ch. 3 R. Kook states that the medieval approach of trying to “prove” religion will not work in our day, and that in place of this, religious leaders should stress justice and righteousness, i.e., the humane values of Judaism.

[6] He recognizes that the real problem for modern Jews is not the scientific or philosophical challenges to Torah, but the ethical ones, and that Torah scholars must explain those concepts that appear to stand in contradiction to modern ethical values. He sees this task as just like what the medievals did in dealing with the physical descriptions of God in the Bible, which contradicted the philosophical notion that God has no form. These sages showed the way out of this problem and in the end the truth of the Torah was understood. R. Kook says that contemporary sages must do the same thing with regard to ethical challenges. If not, people will reject the Torah because they view its message as contradicting what they know to be ethical, that which R. Kook refers to as “the laws of natural morality” (חקי המוסר הטבעיים).

With this in mind, let me quote an amazing passage of R. Kook that I have referred to before. It appears in

Shemonah Kevatzim 1:75 and the translation is by David Guttmann.

[7]

Yir’at Shamayim—fear of heaven—may not supplant the natural sense of morality of a person, for in that case it is not a pure Yir’at Shamayim. The signpost for a pure Yir’at Shamayim is when the natural sense of morality (המוסר הטבעי) that is extant in the straightforward nature of man is improved and elevated by it more than it would have been without it. But if one were to imagine a kind of Yir’at Shamayim that without its input, life would tend to do well and bring to fruition things that benefit the community and the individual, and furthermore, under its influence less of those things would come to fruition, such a Yir’at Shamayim is wrong.

The upshot of this passage is that some (much?) of what passes for piety today is really nothing more than a corrupted religiosity.

This natural morality that R. Kook spoke of was not only in nature, but also in people. This led R. Kook to a unique understanding of the relationship between scholars and masses. Anyone who has studied in a yeshiva knows that it inculcates a certain amount of condescension for the masses. For what could the masses, the typical am ha-aretz, possibly have to offer the scholar? Yet R. Kook saw matters differently, and recognized that there was an element of natural Jewish morality in the masses that was no longer to be found among the scholars, and the scholars ignored this to their own detriment. And let us not forget that the masses that R. Kook was referring to were not like many of our masses who go to day school, yeshiva in Israel, and attend daf yomi before going to work. The East European Jewish masses never opened a Talmud after leaving heder. They were pious and recited Psalms and came to a shiur in Ein Yaakov or Mishnayot, but without having studied in yeshiva, and lacking an Artscroll, the Talmud was closed to them. Incidentally, the rabbis had no problem with this arrangement, unlike today when Talmud study has become a mass movement.

Had the masses in R. Kook’s day had any serious learning, then he couldn’t have said what he did, because his point is precisely that learning “spoils” some of the Jew’s natural morality. Here are R. Kook’s words in Shemonah Kevatzim 1:463:

האנשים הטבעיים שאינם מלומדים, יש להם יתרון בהרבה דברים על המלומדים, בזה שלא נתטשטש אצלם השכל הטבעי והמוסר העצמי על ידי השגיאות העולות מהלימודים, ועל ידי חלישות הכחות וההתקצפות הבאה על ידי העול הלימודי.

This is a an anti-intellectual passage, in which we see R. Kook favoring the natural morality and religiosity of the simple Jew over that of his learned co-religionist. (It was precisely this sort of sentiment that was expressed by Haym Soloveitchik at the end of “Rupture and Reconstruction.”) Can anyone be surprised that this passage was not published by R. Zvi Yehudah? He recognized all too well the implications of these words, which I am only touching on here.

R. Kook continues by saying that the masses need the guidance of the learned ones when it comes to the halakhic details of life. That we can understand, since the masses can’t be expected to know, say, the details of hilkhot Shabbat. But in a passage quite subversive to the intellectual elite’s self-image, R. Kook adds that the learned ones also have a lot to learn from the masses. In fact, if you compare what each side takes from the other, I don’t think there is any question that what the masses give the learned is more substantial than the reverse.

והמלומדים צריכים תמיד לסגל לעצמם כפי האפשרי להם את הכשרון הטבעי של עמי הארץ, בין בהשקפת החיים, בין בהכרת המוסר מצד טעביותו, ואז יתעלו הם בפיתוח שכלם יותר ויותר

In ch. 4 of Li-Nevokhei ha-Dor, R. Kook comes to evolution and here he speaks of the billions of years of history identified by modern science. He says that this is a problem for the קטני דעה who think that evolution is a rejection of God, but those who hold such a position are making a great error. The true believer will be led to even greater wonder at the ways of God when he sees how long it has taken for species to evolve. As for the Creation story, R. Kook begins ch. 5 by telling us that it is not to be understood literally, as Maimonides had already taught. Knowing that some might nevertheless be tied to a literal reading of the opening chapters of Genesis, R. Kook insists that this is not one of the principles of the Torah. (Until a few years ago this was not a principle in the haredi mind either.)

In ch. 5 we see R. Kook’s preference for the evolutionary scheme over the traditional story of creation at one time, and he sees this understanding as bringing us closer to God. Just as we are amazed by the growth of a baby inside the womb, so too we will be in awe at the development of the physical world. He is absolutely clear that the creation story is not a scientific description but is directed towards a moral end:

ויסוד הדבר, שלא דברה תורה כי אם במה שנוגע לכדור ארצינו, וגם זה רק לפי התוכן שיובן הצד המוסרי שנוגע להישרת דרכי האדם הליכותיו החיצוניות ורגשותיו הפנימיים יפה יפה

This is a strong rejection of the neo-fundamentalist hermeneutical acrobatics of people like Gerald Schroeder (and to a lesser extent Nathan Aviezer).

[8] They start with the assumption that the Torah’s Creation story is indeed describing scientific reality, yet until they explained it, no one in history had understood the meaning of the verses. From R. Kook’s perspective, this is a great misinterpretation of what the Creation story is telling us. As for the “young earthers’” objection (which I admit to having never understood) that Shabbat depends on seven 24 hour days of creation, R. Kook disposes of that without much ado:

אין כל מניעה בזה לא מצד הכתובים, ולא מצד חובת קדושת השבת שמכוונת כפי הציור הפנימי של האדם

He continues by saying that other parts of the Creation story can also be explained in a non-literal fashion:

ואפילו אם נפרש עוד יותר על פי משל את הסידור של בריאת האדם, שימתו בגן עדן, קריאת השמות, בנין הצלע, אין דבר מתנגד ליסודי התורה . . . ואין קפידא אם נצייר הנחש כולו ציורי, וכן עץ הדעת על התגלות הנטיה לצאת ממצב המנוחה והתמימיות העדינה

Crucial for R. Kook’s understanding is that that there came a point in human development when man was able to recognize the Divine. Only then could he be described as created in the image of God.

Even before the recent publications, these thoughts of R. Kook were not unknown. Here is what he writes in Iggerot ha-Re’iyah, no. 134:

אין לנו שום נפ”מ אם באמת היה בעולם המציאות תור של זהב [=גן עדן], שהתענג אז האדם על רב טובה גשמית ורוחנית, או שהוחלה המציאות שבפועל מלמטה למעלה מתחתית מדרגת ההויה עד רומה, וכך היא הולכת ומתעלה

The last part of this quotation refers to the evolutionary understanding, in that existence works its way “from the bottom up”.

Returning to Li-Nevokhei ha-Dor, ch. 5, as an example of how the allegory works, R. Kook refers to Eve being taken from Adam’s rib, which cannot be understood literally if we are dealing with an evolutionary scheme. He sees this as a vision, designed to show that family life can only succeed if both husband and wife join together. The wife cannot be a helpmate alone, but has to be joined with her husband. A surface read of this passage might lead one to think that according to R. Kook this “vision” was an actual event that occurred with the historical “first man”, which would means that this first man had a relationship with God. Yet from Shemonah Kevatzim 1:594, which is a parallel passage to the one in Li-Nevokhei ha-Dor, we see that this is not the case.

להשוות סיפור מעשה בראשית עם החקירות האחרונות הוא דבר נכבד. אין מעצור לפרש פרשת אלה תולדות השמים והארץ, שהיא מקפלת בקרבה עולמים של שנות מליונים, עד שבא אדם לידי קצת הכרה שהוא נבדל כבר מכל בעלי החיים, ועל ידי איזה חזיון נדמה לו שצריך הוא לקבע חיי משפחה בקביעות ואצילות רוח, על ידי יחוד אשה שתתקשר אליו יותר מאביו ואמו, בעלי המשפחה הטבעיים. התרדמה תוכל להיות חזיונית, וגם היא תקפל איזה תקופה, עד בישול הרעיון של עצם מעצמי ובשר מבשרי. והודיע הכתוב שקדושת המשפחה קדם להבושה הנימוסית בזמן, וכן במעלה, שאחר ההתעוררות מהתרדמה הוחלט דבר זאת הפעם, ומכל מקום היו שניהם ערומים ולא יתבוששו.

According to R. Kook’s portrayal of humanity’s development in the direction of a stable family unit, there is only one word to describe the story told in Gen. 2, and that is “myth.” While in the popular mind myth often is identical with fairy tale, this is not how scholars understand myths. For them, myths communicate cosmic truths in non-historical story form, and they are not synonymous with legends. My dictionary explains myth as “a usually traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon.” This explanation is a perfect description of what R. Kook writes in the passage just quoted from Shemonah Kevatzim.

The problem is, where do you draw the line? Is it only the stories at the beginning of Genesis that can be interpreted in a non-historical fashion, or has the door been opened to other sections of the Torah as well? R. Kook already confronted this issue in one of his classic letters to his student, Moshe Seidel (

Iggerot ha-Re’iyah, vol. 2, no. 478), whom he had encouraged to study Semitic languages.

[9] R. Kook admitted that there was no clear dividing line, but that the Jewish people as a whole would come to a proper insight.

ואם אין כל יחיד יכול להציב גבול מדויק בין מה שהוא בדרך משל בתורה ובין מה שהוא ממשי – בא החוש הבהיר של האומה בכללה ומוצא לו את נתיבותיו לא בראיות בודדות כי אם בטביעות עין כללית.

Following this, R. Kook raises the issue of what to do if it can be proven that the Torah’s description of matters is not entirely accurate. Often when R. Kook spoke about these matters, he was referring to the Torah’s description of creation vs. what science tells us. Yet I don’t think that this is what he is referring to in this letter. To begin with, he doesn’t speak about issues of science here. He is talking generally about matters described in the Torah that conflict with research (hakirah). These would also include historical descriptions found in the Torah. We must remember that the letter is to Seidel, who was involved in academic Bible study and was struggling with this. I think it is pretty clear that his concern was not with science and creation but with the larger issue of what the Torah recorded vs. what the critical scholars were saying. (Unfortunately, I am informed that Seidel’s letter to R. Kook, which R. Kook is in turn responding to, is not found in the R. Kook archive.)

R. Kook tells Seidel that even if the Torah’s descriptions (“the commonly accepted description”) are not accurate, there must be an important and sacred purpose for these matters to have been presented in this way, rather than being described in an exact fashion. In order to show that this is a proper approach, R. Kook brings two amazing parallels. The first one is the law of

yefat toar. In my earlier post dealing with developing morality, available

here, I quoted R. Kook’s other recently published comments about

yefat toar. Here is making a different point. He refers to the Talmud in

Kiddushin 21b which states that this entire law is a concession to human passions, but it is not proper. The proper thing would be for a Jewish soldier never to do this, but since in the real world this sort of thing will happen, the Torah provides a context for it to be done in a more civilized manner.

[10] The parallel R. Kook sees is that just like the morality described in the law of

yefat toar is not perfect, but rather a concession to human weakness, so too descriptions of various things in the Torah need not be “perfect”, that is, historically accurate. There are times when for its own purposes the Torah needs to describe matters in ways that will accomplish certain goals, even if the descriptions are not “true,” i.e., historically true.

The next parallel he offers is Ex. 18:19, which describes Mt. Sinai at the time of the Revelation and states that “its smoke ascended like the smoke of the lime pit.” Rashi, based on the Mekhilta, comments that this reference to the smoke being like a lime pit was “to explain to the ear that which it can understand (לשבר את האזן).” In other words, it wasn’t really like a lime pit but this description is used to accomplish a larger goal. R. Kook develops this concept, and refers to this Rashi. Here is the passage in full:

ואם נמצא בתורה כמה דברים, שחושבים אחרים שהם לפי המפורסם מאז, שאינו מתאים עם החקירה של עכשו, הלא אין אנו יודעים כלל אם יש אמת מוחלטת בחקירה הזמנית, ואם יש בה אמת, ודאי יש גם מטרה חשובה וקדושה שלצרכה הוצרכו הדברים לבא בתיאור המפורסם ולא המדויק, כמו שהוא פשוט במושגים הרוחנים ובכמה יסודי מעשה, ש”דבר תורה כנגד יצה”ר” או “לשבר את האזן.”

Elsewhere, in Eder ha-Yekar, pp. 37-38, R. Kook explains that the Torah can describe events in a way not in accord with the astronomical or geological (i.e., historical) truth. This is done in order for the Torah to accomplish its goal, which is not focused on such matters but rather on

ידיעת האלהות והמוסר וענפיהם בחיים ובפועל, בחיי הפרט, האומה והעולם

In words very similar to those in his letter to Seidel, R. Kook writes there:

כבר מפורסם למדי שהנבואה לוקחת את המשלים להדרכה האנושית, לפי המפורסם אז בלשון בני אדם באותו זמן, לסבר את האוזן מה שהיא יכולה לשמוע בהוה, “ועת ומשפט ידע לב חכם”, וכדעת הרמב”ם וביאור הרש”ט במורה נבוכים סוף פרק ז’ משלישי, ופשטם של דברי הירושלמי שלהי תענית לענין קלקול חשבונות של תשעה בתמוז.

What R. Kook is saying here is that prophecy uses what is “widely accepted”, even if mistaken, as well as the forms of speech current among contemporary listeners.

[11] With this conception, one can’t be disturbed if the Torah or other prophets describe matters not in accord with the facts as we know them today, because the immediate audience of the prophet

did think that these were the facts. So, for example, the Torah does not describe a universe billions of years old because that was not part of the mental conception of the ancient Israelites. What is new in this passage is R. Kook’s reference to Maimonides and Shem Tov’s commentary.

He doesn’t explain what he has in mind when he refers to Maimonides, but by examining Shem Tov’s commentary to Guide 3:7, which R. Kook also refers to, all is revealed. Here Shem Tov is discussing Maimonides’ view of Ezekiel and a scientific error the prophet made. Shem Tov concludes his discussion with the following revealing words:

ידבר הנביא בענינים העיוניים במשפט החכם ולא ידבר בהם כמו נביא אם שאמרם הנביא

What this means is that when the prophet is speaking about philosophical or scientific matters, he is speaking from his own wisdom, not prophetic insight. Shem Tov’s point is that the prophet will assimilate his prophetic message to his own words, and the latter, based as they are on his own life experience and knowledge, could also contain error.

This is all based on what Maimonides himself writes in

Guide 2:8. Here he explains that there is a dispute if the heavenly spheres emit sounds. The Sages believe they do, and Aristotle rejects this. Maimonides adopts Aristotle’s view and explains that the Sages were mistaken. In

Guide 3:3 Maimonides identifies the wheels (

ofanim) in Ezekiel’s vision with the spheres, and if you examine Ezekiel 1:24 and 10:5 you find that the prophet describes the wheels (=spheres) as producing sounds. The upshot of this is that according to Maimonides Ezekiel’s prophecy incorporated a mistaken scientific view, a view which he points out was later shared by the Sages of Israel. This explanation of Maimonides, quoted from Narboni, is recorded by Shem Tov in his commentary to

Guide 3:7.

[12] As mentioned, this is what R. Kook refers the reader to.

Ralbag, commentary to Gen. 15:4 and to Job, end of ch. 39, also refers to Maimonides’ view that the prophets could be in error about scientific matters. He refers in particular to Ezekiel’s scientific error, and expresses his agreement with Maimonides’ position. In his commentary to Job he explains:

ספר זה עם ספורו שאר הדברים הנעלמים להיות זה נעלם לאיוב כי בנבואה יבואו כמו אלו הענינים לפי המקבל . . . שכבר יגיע לנביא דבר כוזב בעת הנבואה, במה שאין לו מצד שהוא נביא מצד הדעות אשר לו בענינים ההם.

In other words, prophetic books might record mistaken ideas because that is what the prophet thought. Ralbag gives another example of this. In Gen. 15 Abraham was told to look at the sky and just as he could not count the stars of heaven so too his children will be so numerous. According to Ralbag, this is an example of a prophet receiving false information in accord with his mistaken conception. Since Abraham falsely believed that there are many stars, his prophecy contained this false conception, while in reality according to Ralbag there are actually a limited number of stars.

Ralbag further explains his view of the stars in Milhamot ha-Shem 5:1:52, which has not yet been published and is quoted from manuscript in the Birkat Moshe edition of Ralbag on Genesis, pp. 222-223. Here Ralbag rejects the view of those who thought that there were many unseen stars and asserts that the only stars are those that can be seen. (Maimonides, Guide 1:31, states that the number of the stars is unknown.) He mentions that others had assumed that there were unseen stars because otherwise the prophecy of Abraham would not make sense. If you look up at the stars there aren’t so many of them, and therefore, what type of promise is it that Abraham’s descendants will be as many as the stars?

Unlike in his commentary to Genesis, here Ralbag does not claim that Abraham’s prophecy was incorrect when it came to the number of stars. Instead, he states that the meaning of the verse is not that Abraham’s descendants will be so many that they can’t be counted. Rather, just like it is difficult to count the stars, so too it will be difficult to count the descendants of Abraham because they will be so many. His proof for this contention is Moses’ words to Israel, Deut 1:10: “The Lord your God hath multiplied you, and, behold, ye are this day as the stars of heaven for multitude.” Moses says this even though he had already counted the Children of Israel. Yet because they were so many that it was difficult to count them, he refers to them as “the stars of heaven”. According to Ralbag, this proves that the comparison with the stars does not mean “too many to count”, but only “difficult to count”.

Ralbag also cites a talmudic passage (Berakhot 32b) which speaks of an enormous number of stars (three hundred and sixty five thousand myriads). This contradicts his own view that the number of stars are quite limited. Yet Ralbag is not troubled and declares, in words that would get him banned today:

שבכמו אלו הדברים לא נרחיק שיהיו לקצת חכמינו אז דעות בלתי צודקות, כמו שיזכרו שחכמי ישראל היו אומרים שהגלגל קבוע ומזלות חוזרים ומה שדומה לזה.

In his commentary to Genesis 15:4 he writes:

לא יחוייב שיהיו אצל הנביא כל הדעות האמיתיות בענין סודות המציאות

Obviously, if you are prepared to say that great prophets such as Abraham and Ezekiel were wrong in scientific matters, it is only natural to assume the same thing when it comes to the Sages.

Of course, we know today how wrong Ralbag was. In fact, it is only in modern times that one can really appreciate Abraham’s prophecy. Later, in Gen. 22:17, he is told that his descendants will be as numerous as the sand and as the stars in the heaven. Centuries ago I think many people must have wondered about this verse. They could understand the promise that his descendants would be like the sand since the sand is so numerous it can’t be counted. Yet how is this comparable to the stars, since anyone can look up at the sky and see that there aren’t that many stars at all? Thus, pre-modern man should have been troubled since the two parts of the verse don’t correspond, even though they are supposed to. It is only with the invention of telescopes that people could see that the two parts of this verse, the sand and the stars, are really saying the same thing. Scientists now believe that the amount of stars runs into the sextillions and that there are more stars than grains of sand on the earth!

Returning to R. Kook’s letter to Seidel, he also refers to the end of Ta’anit in the Jerusalem Talmud. What is this about? According to Jeremiah 39:2 the Jerusalem city walls were breached on the ninth day of Tamuz. Yet JTa’anit 4:5 states that this occurred on the seventeenth of Tamuz. How to make sense of this contradiction? The Jerusalem Talmud answers as follows:

קלקול חשבונות יש כאן

Korban Edah explains:

מרוב הצרות טעו בחשבונות ולא רצה המקרא לשנות ממה שסמכו הם לומר כביכול אנכי עמו בצרה

In other words, the book of Jeremiah records mistaken information, but that is because it chooses to reflect the mistaken view of the people, rather than record the accurate facts. As the final words of

Korban Edah explain, there are more important considerations for the prophet than to be accurate in such matters. R. Kook sees the lesson of this talmudic passage as applicable to elsewhere in the Bible, namely, that absolute accuracy in its descriptions (both scientific and historical) is not vital and can therefore be sacrificed in order to inculcate the Bible’s higher truths. R. Kook does not tell us how far to take this principle, and no doubt he himself was not sure.

[13] The only thing he could say was that these matters would be settled by, as mentioned already, החוש הבהיר של האומה

Another example of a biblical book containing incorrect information is found in Nehemiah 7:7, as explained by the medieval commentary attributed to Rashi. After noting that the numbers given in Nehemiah ch. 7 are not always the same as those mentioned in the book of Ezra, “Rashi” states:

ולא דקדק המקרא בחשבונות כל כך אבל הכלל שוה . . . ועל זה הכלל סמך כותב הספר ולא דקדק בחשבון הפרטיות כל כך.

What this means is that the author of the book of Nehemiah was not careful in the details he recorded, as long as the big picture—in this case, the total number of people—was correct. How many other places in the Bible can we apply this insight to?

The fourteenth-century R. Eleazar Ashkenazi ben Nathan ha-Bavli has an even more radical approach, as he believes that there are inaccuracies in the Torah itself.

[14] It is true that at times he is quite conservative. For example, he rejects Ibn Ezra’s assumption that there are post-Mosaic elements verses in the Pentateuch.

[15] He also strongly rejects the aggadah that the Land of Israel was not included in the Flood,

[16] because the verse tells us that all life on earth was destroyed: ואין לחוש על דבר משמכחיש גופי התורה

Yet his more “liberal” side is seen many other places. For example, he assumes that the extremely long lifespans found at the beginning of Genesis are not to be taken literally (p. 29).

וימי חייהם אז היו כימי חיי אנשי דורנו לא פחות ולא יותר כי לא היו אז מזהירים כשמש ולא חזקים כנחושה, אבל היו מבשר ודם ומזרע אשה ומדם נדותה ככל אשר אנחנו עושים פה היום

If people never lived so long, why were these number included in the Torah? R. Eleazar claims that Maimonides’ approach is to regard the lengthy lifespans as simple figures of speech, not meant to be taken literally any more than the statement that the Land of Israel was flowing with milk and honey or that the cities in Canaan were “fortified up to Heaven” (Deut. 1:28).

[17]

He also offers another explanation for the lengthy lifespans, namely, that the Torah recorded what the popular belief was, no matter how exaggerated, and Moses was not concerned about these sorts of things. In other words, just like today people say that the Torah is not interested in a scientific presentation of how the world was created, R. Eleazar’s position is that the Torah is not interested in a historically accurate presentation. In his mind, this has nothing to do with the Torah’s goals, and therefore there was no reason for the Torah not to present matters as they were believed at the time, even if these perceptions were inaccurate. The important thing, he says, is that the people would know that from the creation of the world until Israel stood at Sinai was close to three thousand years. This would help solidify belief in creation. The records of lifespans are just a means to illustrate this information.

[18] He adds that when it came to events closer to Moses’ time, Moses was careful in preserving a more accurate accounting, while leaving the stories of the distant past cloaked in legend.

There are other ways rationalists have dealt with the lengthy lifespans. For example, R. Nissim of Marseilles regards these years not as indicating an individual life, but rather the “lifespan” of the way of life (i.e., laws, customs) instituted by the figure in question, or the time until another one like him arose. He also assumes that when the Torah says that someone bore a son, it doesn’t have to mean a literal son. Here is what he writes in Ma’aseh Nissim, p. 274:

יש מי שפירש שהכונה בחיים ההם קיום נמוסיו והנהגותיו הזמן [בזמן] הנזכר, בין בחייו בין אחר מותו. כי אלו, אפשר שהיו אנשי שם, מחקים חוקים ונימוסים, ומנהגים במידותיהם, גם במאכלם ומשתיהם ובמלבושיהם, ואחר הזמן ההוא אפשר שנשתכח הכל ובחרו דרך אחרת. או תאמר, שלא קם כמוהו עד זה הסך מן השנים במעלת ידיעת ההנהגה לבני דורו. ובזמן ההוא קם כמוהו במעלה, נמשך לדעתו וכונתו, ונחה רוחו עליו כאשר נחה רוח אליהו על אלישע. ואם לא ראה הראשון זה שקם אחריו ולא היה בזמנו, אפשר למד מספריו או התבונן בדבריו המקובלים, ועל זה כתוב: “ויולד” שהוליד בדמותו במעלה, כאלו הוא הוליד האיש ההוא מאשר הוא בעל הדעת ההוא שלמדוהו.

In support of this approach, he refers to Va-Yikra Rabbah 21:9 which cites an opinion that Scripture intimated to Aaron that he would live 410 years. Although the Torah tells us that he only lived to 123 (Num. 33:39), the Midrash says that the righteous High Priests in the First Temple are called by Aaron’s name. In other words, they represent the spirit of Aaron, so in that sense it can be said that he lived so many hundreds of years. So too, R. Nissim thinks, when Scripture speaks of other people living so many hundreds of years it is to be understood in this fashion.

Another approach was suggested by R. Moses Ibn Tibbon, who is quoted by R. Levi ben Hayyim.

[19] According to Ibn Tibbon, the years given for people’s lives are actually the years of the dynasties they established.

[20] (His other suggestion is the same as that of R. Nissim, mentioned above.):

והחכם ר’ משה פירש, כי כל אחד מאלו היה מלך או הניח נימוס, וכל זמן התמדת מלכותו ומלכות זרעו, או כל ימי המשכות נימוסו, קרא דור אחד, כאלו היה המלך או מניח הנימוס חי, וטעם “ויולד בנים ובנות” כי לאורך הזמן רבו ועצמו בני מלכותו או אנשי דתו, ושלחו קצתם אל ארץ אחרת.

R. Levi ben Hayyim offers basically the same approach (p. 326):

ונראה לי כי הדורות הנזכרים היו ראשי אבות, וזרע כל אחד נקרא בשמו כפי מספר השנים ההם. כי כל אחד, כמו שנאמר, הוליד בנים ובנות, כמו שנראה היום, עד שנשקע השם מהדורות הבאים אחריו, וקח מאתו זרע איש אחד מפורסם, וקראו בני זרעו ומשפחתו על שמו זמן מה, וכן התמיד עד שנתחדש דור אחר, נקרא [!] בניו ובני בניו על שמו [צ”ל שם] חדש. והורה ספור הדורות ההם מאדם ועד זמן משה על חדוש העולם.

To be continued

* * *

The new semester of Torah in Motion has just begun. The first figure I am dealing with is R. Elijah Benamozegh. You can sign up to participate in the classes

here.

You can also sign up for the classes of Moshe Shoshan, Abe Katz, R. Daniel Feldman, and William Gewirtz. Dr. Gewirtz, who has published on the Seforim blog, will be giving three FREE special classes dealing with various aspects of time in Jewish law. This is a topic that few have been able to master and the classes promise to be a treat.

Even if you can’t watch the classes live, videos and audio are sent to you so that you can watch or listen at your convenience.

Also from Torah in Motion, information will soon be coming about the July trip to Central Europe that I will be leading.

[1] For the proper explanation of the etymology of Marheshvan, see Ari Zivotfsky’s article in

Jewish Action, Fall 2000, available

here. See also Abraham Epstein,

Mi-Kadmoniyot ha-Yehudim (Vienna, 1887), pp. 23ff. Zivotofsky does not offer any sources for the mistaken etymology that Heshvan is bitter (

mar) because it has no holidays in it. I don’t know the first appearance of this notion, but it already is found in R. David Meldola,

Moed David (Amsterdam, 1740), p. 64a.

[2] Among rishonim, Ibn Caspi had already stated that Adam was not the first man. See

Matzref ha-Kesef, pp. 16-17 (contained in

Mishneh Kesef, vol. 2). In order to understand what Ibn Caspi is saying in this passage, one needs to be attuned to his elusive style. See also his commentary to

Guide 1:14, where he understands Maimonides to be saying that the Adam of Genesis is really referring to Moses.

[3] Rishonim already proposed that the word האדם in Gen. ch. 2 refers to humanity, rather than an individual person. See e.g., Ibn Ezra to Gen. 2:8, who states that this interpretation is a secret, i.e., not designed for the masses. See also his commentary to Ex. 3:15. R. David Kimhi also felt that this “truth” should be kept from the masses, who should instead be taught a different “truth”, namely, the Adam and Eve story in a literal fashion. See his esoteric commentary to Genesis, printed in Louis Finkelstein, ed.,

The Commentary of David Kimhi on Isaiah (New York, 1926), p. LIV:

עתה אשוב לפרש הנסתר אשר מפסוק וייצר ה’ א-להים את האדם (בראשית ב, ז) עד זה ספר תולדות אדם (בראשית ה, א) ותחלה אומר כי האדם הנזכר מפסוק זה עד זה ספר תולדות אדם הנגלה הוא על אדם הראשון והנסתר הוא על שם המין ושניהם אמת אך הנגלה הוא להמון והנסתר הוא ליחידים שהם סגולת ההמון.

Here is how he understands the Garden of Eden (ibid.):

עדן הוא משל לשכל הפועל הוא העדן האמתי הרוחני והא-ל נטע בו גן מקדם בראש בריותיו כשברא השכלים הנבדלים.

[5] See Eitam Henkin’s post

here. For another post by Henkin on this book, see

here. English readers are probably unaware of Henkin, the son of R. Yehudah Herzl Henkin. In the last few years he has really created a reputation for himself as he has authored a number of important articles which show an incredible amount of knowledge on the history of Torah Judaism in modern times. He has also written a sefer, soon to be published, which deals with the halakhot of bugs in food. Unlike the rage today, he rejects the extreme positions, one of which is that due to bug infestation, strawberries are no longer permitted to be eaten. See e.g.,

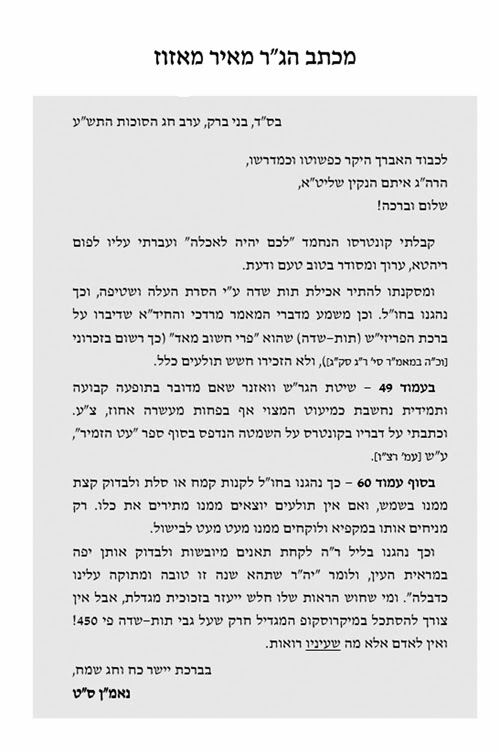

here. Henkin’s book will carry the following haskamah of R. Meir Mazuz.

[6] R. Jehiel Jacob Weinberg would later argue against trying to “prove” Judaism in the medieval fashion. In the post-Hume and post-Kantian world I thought that this was pretty much agreed upon by everyone. How wrong I was can be attested to all who attended my lecture on Maimonides at the 2008 New York Limmud conference and recall the dispute that took place afterwards. An individual who is involved in kiruv adamantly insisted that the major doctrines of Judaism can be proven to the same degree of certainty as a mathematical proof, and that these truths can thus be proven to non-Jews (who if they don’t accept the proofs are being intellectually dishonest). In this conception, there is no longer room for “belief” or “faith”; since the religion has been “proven” we can only speak of “knowledge”. The notion that Judaism could not be proven in this fashion was, I think, regarded by him as akin to heresy. I have had a lot of contact with “kiruv professionals” and had never come across such an approach. Yes, I know that people speak about the Kuzari proof for the giving of the Torah. However, I always understood this to be more in the way of a strong argument rather that an absolute proof, with the upshot of the latter being that one who denies the proof is regarded as intellectually dishonest or as a slave to his passions. I also know R. Elchanan Wasserman’s strong argument in favor of the viewpoint expressed by my interlocutor (see

Kovetz Ma’amarim ve-Iggerot, pp. 1ff.), but before then had never actually found anyone who advocated this position, lock, stock and barrel. So the question to my learned readers is, is there a kiruv “school” today which does outreach based on the “Judaism can be proven” perspective?

[8] In his latest book,

God According to God, Schroeder—who according to his website teaches at Aish ha-Torah— “goes off the haredi reservation” in a much more serious way than Slifkin. Here is how his website describes the book: “In

God According to God, Schroeder presents a compelling case for the true God, a dynamic God who is still learning how to relate to creation.” See

here. I daresay that one would be hard-pressed to find even a Modern Orthodox rabbi who would not regard this view of an imperfect God as a heretical position.

In a future installment I will deal with Aviezer who unlike Schroeder, has real Judaic learning. Unfortunately, despite his scientific expertise, Schroeder makes numerous errors when he deals with the Jewish side of things. From what I see on the internet, it appears that a majority of his readers are non-Jewish, so these errors will not be noticed by them. Yet they are bound to be annoying to educated Jewish readers. Let me give just a few examples from his new book, God According to God.

P. 11: “The Hebrew word for ‘slave’ is ‘worker’ with all the connotations that differentiate the modern concept of slave from that of a worker.” He then apologetically describes the laws of slavery without distinguishing between the Hebrew slave and the Canaanite slave, and apparently without realizing that the latter was indeed a real slave. See Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh Deah 158:1, where R. Moses Isserles writes:

מותר היה לנסות רפואה בעבד כנעני אם תועיל

P. 11: “Returning an escaped slave to the master was absolutely forbidden (Deut. 23:15-16).” Yet we are not Karaites and a glance at Rashi will show that this is not as “liberal” a law as he makes it out to be.

P. 22: [T]he ancient biblical commentators, those whose writings predate by many centuries the discoveries of modern science (writers of the Talmud, ca. 400; Rashi, ca. 1090; Maimonides, ca. 1190; Nahmanides, ca. 1250), learned from the detailed wording of Genesis that the universe is young and old simultaneously. These ancient commentators actually discuss what science has only recently discovered, that the flow of time is flexible.”

P. 23: “Moses Maimondes refers to a madah teva, the science of nature.”

P. 195: “The [biblical] Hebrew word le’olam has three root meanings: “forever,” “hidden” and “in the universe”.

Nothing I have said should be taken to imply that Schroeder does not have what to offer. However, before he publishes anything it should be reviewed by a Torah scholar, much as I would expect a talmid chacham writing on science to have his writing reviewed by a professional scientist.

[9] See

Iggerot la-Re’iyah, vol. 1, no. 108. Seidel would later teach at Yeshiva College where some of the Roshei Yeshiva were upset with his views. See Ari Shvat, “Hahlatato shel ha-Rav Kook le-Tzamtzem et Hazono le-Limud Mehkari-Madai bi-Yeshivat Merkaz ha-Rav,”

Talelei Orot 15 (2009), pp. 149-174.

[10] In a recent issue of

Iturei Yerushalayim (Sivan 5769, pp. 9-10), R. Shlomo Aviner responds to a soldier who in all seriousness wanted to apply the law of

yefat toar today with regard to Palestinian women. The soldier had in mind the understanding that rape of a

yefat toar is permitted during battle.

Complete details can be found in the Encyclopedia Talmudit entry for yefat toar. There is a lot in this entry which will distress any reader, and according to the Sages, that is the way people should feel, for the entire law was a concession to human weakness. That is, it was a necessary evil, not something that people should strive for or feel proud of. This is how the entry in the Encylopedia Talmudit begins:

היוצא למלחמה וראה בשביה אשה נכרית וחשק בה, מותר לו לבא עליה – על כרחה.

In other words, it is permitted to rape a captive woman, and it was based on this understanding that R. Aviner was asked the question. Yet it is probably also the case that this view is not held by all. I say this since the Encyclopedia Talmudit entry itself records that there are those who require the woman to be converted before sex, and there are also those who state that the woman cannot be converted against her will. Although I haven’t compared all the positions, it is likely that there is some overlap here, i.e., authorities who require the woman to be converted and also hold that the conversion has to be an act of her free will.

Yet it is also the case that plenty of authorities do permit rape of a yefat toar (including a married woman), either on the battlefield or later. In his commentary to Gen. 34:1, Nahmanides writes:

כל ביאה באונסה תקרא ענוי, וכן לא תתעמר בה תחת אשר עניתה.

I have no doubt that today, when everyone would be horrified by this behavior, and it is forbidden in all civilized societies (and even uncivilized ones), such an action would not be permitted even as a concession to human weakness. I can’t imagine that anyone in our day would condone rape, no matter what the circumstances, and certainly no one would defend the following opinion quoted in the Encyclopedia Talmudit:

היתה השבויה קטנה, כתבו אחרונים שביאה ראשונה – לסוברים שהיא לפני גירות – מותרת אף בקטנותה.

From R. Aviner’s reply we see that he doesn’t believe that the yefat toar law has any applicability today:

בוודאי שאין דין יפת תואר נוהג בימינו, ואני תמה על השאלה הזאת שהנך שואל למעשה, שכידוע לא דיברה תורה אלא כנגד יצר הרע, והרי אדם צריך להלחם ביצר הרע ולא לחפש היתרים ליצר הרע. וכבר כתב רבי יהודה החסיד בספר חסידים [סי’ שעח] שיש דברים שהתורה התירה אבל אם יעשה אותם האדם הוא יבוא לדין עליהם שהרי התורה רק התירה בגלל יצר הרע. ואם אדם נותן שחרור ליצר הרע, הוא ייתן את הדין . . . לגופו של עניין, כל הדין הזה הוא בשביה, ולא שאדם ילך לבתים של אויבים ויעשה שם נבלות, והרי נשים אינן שבויות צה”ל, וגם אם יש שבויה, בוודא שצה”ל לא ירשה כזו נבלה . . . בסיכום, זה לא שייך כלל וכלל. הרחק ממחשבות אלו, אלא אדרבה למד הרבה בספר מסילת ישרים.

In this, R. Aviner is following the approach of R. Kook who speaks of the need to rise above the law of yefat toar. In my previous post dealing with developing morality, referred to in the text, I quoted R. Kook as follows:

כל לב יבין על נקלה כי רק לאומה שלא באה לתכלית חינוך האנושי, או יחידים מהם, יהיה הכרח לדבר כנגד יצר הרע ע”י לקיחת יפת תואר בשביה באופן המדובר. ומזה נלמד שכשם שעלינו להתרומם מדין יפת תואר, כן נזכה להתרומם מעיקר החינוך של מלחמת רשות.

Note that R. Kook speaks of תכלית חינוך האנושי and not Torah education.

We have recently seen the publication of Torat ha-Melekh (which I will discuss in a future installment of this post). When I told a friend about the question of the soldier to R. Aviner, he commented, only half-jokingly, that we will probably soon see a book on how Israeli soldiers can institute the law of yefat toar in modern times.

Finally, I would be remiss in not mentioning that R. Meir Simhah of Dvinsk basically turns the entire law of yefat toar into something completely theoretical, much like ben sorer u-moreh. I say this because R. Meir Simhah assumes that the law is not applicable in a war where the enemy could be holding Jewish prisoners, which in the real world is always the case. Here are his words in Meshekh Hokhmah, Deut. 21:10:

נראה דהוא תנאי בהיתר יפת תואר, שדוקא אם ה’ נותן האויב ביד ישראל. אבל כדרך המלחמות שאלו שובים מהם, והאויב שובה מהם, והדרך כשעושים שלום או בתוך המלחמה, מחליפים שבויים שאינם ניאותים עוד למלחמה. אם כן יתכן כי עבור היפת תואר שמגיירה ונושאה לאשה בעל כרחה, יעכבו ישראל חשוב ונכבד, על זה לא הותר היפת תואר.

[11] The exact same point is made by the Gaon R. Shlomo Fisher,

Beit Yishai (Jerusalem, 2004), p. 361:

. . . העיקר גדול שהשרישו לנו הקדמונים שדברה תורה כלשון בני אדם. והכונה היא לאותו לשון שדברו בו בני אדם באותו הדור שבו נאמרו הדברים.

Fisher uses this insight to explain Zechariah 4:10: שבעת אלה עיני ה’ המה משוטטים בכל הארץ

According to Fisher—and this is an incredible insight for a traditional interpreter (although it is already noted in the International Critical Commentary)— this verse alludes to the שבעה כוכבי לכת. These are the seven heavenly bodies identified already by ancient Babylonian astronomers: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, moon, and sun. Yet with the invention of the telescope we now know that there are more planets, meaning that Zechariah’s prophecy was based on a scientific error. But as Fisher explains, this is not a problem because as mentioned, prophecy is given in accord with the knowledge of the generation. Fisher adds that prophecy is also given in accord with the knowledge of the prophet, which in this case as with Ezekiel was based on a scientific error.

כי הנבואה תבא לו לנביא לפי תמונת העולם שבלבו

As an aside, I wonder why no one has tried to put Fisher’s book under a ban. While Slifkin stated that the Sages didn’t know everything about science, Fisher goes further and says that even the prophets didn’t know it all. He adopts the same approach to explain why classic Kabbalistic texts are based on outmoded scientific assumptions:

שחכמת הקבלה מיוסדת על תמונת העולם וחוקי הטבע שלפי חכמי יון, כגון, מציאות הגלגלים, ז’ כוכבי לכת, וד’ יסודות, וחומר וצורה. וההנחה שכל דבר נמשך למקורו.

Since I deal with R. Eleazar Ashkenazi ben Nathan ha-Bavli in this post, it is worth calling attention to his original understanding of the word שבועה. He sees it as related to the word seven, meaning that one who breaks an oath sins against God who controls the seven heavenly spheres. See Tzafnat Paneah, ed. Rappaport (Johannesburg, 1965), p. 69 (I think he means the seven spheres each of which contains a heavenly body, as opposed to the eighth sphere which contains the so-called כוכבי שבת, or fixed stars):

כי שם נשבעו בשבועת האלה. כי מי שיעבור על הברית ירבצו בו אלות מכח השבעה הגלגלים וזה סוד שם שבועה כי חלל שם ה’ המנהיג השבעה הגלגלים.

[12] Fisher,

Beit Yishai, p. 361, accepts this interpretation of Maimonides. Ibn Caspi, Commentary to

Guide 2:8, does not believe that Ezekiel’s actual prophecy could contain error. Rather, the error came during a dream of Ezekiel, not an actual prophecy. He also distinguishes between Sages who can err, as they are using their wisdom, and prophets who during actual prophecy do not err. However, when they are not prophesying they are susceptible to error like anyone else.

[13] Shalom Carmy took note of R. Kook’s comments and raised the following questions, without offering any answers:

It seems obvious that Rabbi Kook doesn’t advocate wholesale rejection of biblical statements. To do so would render Tanakh useless as a source of history. Under what circumstances would he countenance “deconstruction” of the text? Only where biblical texts contradict each other or rabbinic statements? Whenever the text appears to contradict well-attested Near Eastern documents? When the exact historicity is immaterial in the judgment of the exegete, to the import of the text? When the exegete detects rhetorical elements in the biblical text itself that point toward such interpretation?

See “A Room With a View, but a Room of Our Own,” in idem, ed., Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah (Northvale, 1996), pp. 23-24.

[14] As Epstein,

Mi-Kadmoniyot ha-Yehudim, pp. 125ff., has shown, Abarbanel used R. Eleazar’s commentary, even though he does not mention him by name (a characteristic that Abarbanel shows at other times as well).

[15] Tzafnat Paneah, p. 46.

[16] Ibid., p. 36. I think one can call this a conservative position with regard to biblical interpretation, but the language he uses to reject the aggadic view, הבל הוא, is quite provocative.

[17] In

Guide 2:47 Maimonides says that the people mentioned in the Bible who lived so long were exceptional in this respect, either because of their diet, mode of living, or due to a miracle. R. Eleazar obviously does not see this as reflecting Maimonides’ true view.

ואל תתמה על זה ואל יקל בעיניך זאת התחבולה הנכבדת שנתכוון אליה כדי לאמץ האמנת החדוש . . . ולזה הוצרך ע”ה לספר לנו חשבון השנים שעברו מזמן חדוש העולם עד זמננו, וזה היה עיקר גדול וצורך נפלא.

[19] Livyat Hen, ed. Kreisel (Beer Sheva, 2004), pp. 324ff. Here is the place to congratulate Howard Kreisel on the publication of the two volumes of

Livyat Hen as well as R. Nissim of Marseilles’

Ma’aseh Nissim. As long as people study Jewish philosophy, they will use these editions. R. Joseph Kafih spent the last night of his life studying

Ma’aseh Nissim. See Avivit Levi,

Holekh Tamim (n.p., 2003), p. 226.

[20] R. Eleazar Ashkenazi,

Tzafnat Paneah, p. 29, cites this approach in the name of Ibn Ezra, but he does not tell us where it is to be found in Ibn Ezra’s Torah commentary or other works.

אבל המשמע מדברי החכם ראב”ע ז”ל שהזקנים היו ראשי האבות לא שחיו המה כל כך.