Further Comments by Marc Shapiro

Further Comments

By Marc B. Shapiro

I had thought that this would be my last post of the current batch, but it turned out to be too long. So I have divided it into two parts. Here is part no. 1.

The volumes Shomrei Mishmeret ha-Kodesh, by R. Natan Raphael Auerbach, have just appeared. Here is the cover.

This book is devoted to the Auerbach family, which was one of the great rabbinic families in Germany. They were the “A” in what was known as the ABC rabbinic families (the others being Bamberger and Carlebach). Over 150 pages are devoted to R. Zvi Benjamin Auerbach, who was the most prominent of the Auerbach rabbis. He was also the publisher of Sefer ha-Eshkol, to which he added his commentary Nahal Eshkol. In a number of posts I dealt with Auerbach’s edition of Sefer Ha-Eshkol, and discussed how both academic scholars and traditional talmidei hakhamim have concluded that the work is a forgery.1 Readers who are interested in the details can examine the earlier posts. In this newly published volume, which was called to my attention by Eliezer Brodt, the author speaks briefly about the Sefer ha-Eshkol controversy and responds to those who, in his words, continue to defame a gadol be-Yisrael (p. 382):

הממשיכים לבזות גדול בישראל ולהכפישו באופן אישי

In the note the author refers to Moshe Samet, who earlier had dealt with Sefer ha-Eshkol, and also to one of my posts on the Seforim Blog. While Seforim Blog posts have been cited in English scholarly writings, as far as I know this is the first time that there has been citation in a Hebrew volume.

I understand why members of the Auerbach family might feel obliged to defend him. (Yet one of my college suitemates was a descendant of Auerbach, and it didn’t seem to trouble him when I told him about the controversy.) Why a respected rabbi would forge a book is not something I want to get into now. In the earlier post I assumed that he was schizophrenic, as when it comes to Sefer ha-Eshkol I can’t think of any ideological reason for his actions. (Samet, He-Hadash Assur min ha-Torah [Jerusalem, 2005], p. 152 n. 235, identifies as one of Auerbach’s motivations: מגמה אורתודוקסית).

As for the argument that since he was a leading rabbi we must therefore assume that he couldn’t have done such a thing, this is disproven by all the recent examples of well-known rabbis who were involved in a variety of types of improper behavior. Before they were exposed, no one could ever have imagined what we learnt, and everyone would have been 100 percent sure that these rabbis could not possibly have been involved in such activities. This simply shows that that just because someone is a well-known rabbi we don’t have to automatically conclude that he is innocent no matter what the evidence says.

In many of the recent cases, at least the ones dealing with sexual abuse, the rabbis no doubt suffered from some sort of mental illness, as I can’t imagine that men who did so much to influence people positively and help them were complete frauds. I think that Auerbach must also have had some psychological issues, and this is actually the best limud zekhut. For once we assume this, it means that we don’t have to view the rest of his illustrious career and achievements as fraudulent. In short, he had a problem and it manifested itself in his forgeries. Yet I admit that I can’t prove my supposition, and at the end of the day we will probably never be able to explain definitively why Auerbach would forge the text any more than we can explain how another great figure, Erasmus, forged a patristic work and attributed it to Saint Cyprian.2 Anthony Grafton, who has written an entire book on the subject, sums up the matter as follows: “The desire to forge, in other words, can infect almost anyone: the learned as well as the ignorant, the honest person as well as the rogue.”3

Unfortunately, Shomrei Mishmeret ha-Kodesh does not seriously deal with any of the evidence that has led to the conclusion that we are dealing with a forgery. (For reasons I can’t get into now, I find it completely implausible that someone in medieval times forged the work and Auerbach was duped. But let me make one point: Auerbach claimed to be working from a very old manuscript, and yet this “manuscript” contains material from the 17th and 18th centuries.). Since the author mentions Sefer ha-Eshkol vol. 4, which was published in 1986 together with the Nahal Eshkol, I once again renew my call for this manuscript to be made public and for some explanation to be given as to where it comes from, since Auerbach’s many defenders were unaware of it. The fact that a portion of Auerbach’s manuscript (i.e. his copy of the supposed medieval manuscript) mysteriously surfaced so many decades after Auerbach’s death, and that we are told nothing about it or even shown a picture of it, certainly raises red flags. As I noted in one of my previous posts, the Nahal Eshkol published here has a reference to a book that only appeared after Auerbach died. This means that quite apart from Sefer ha-Eshkol, we also have to raise questions about whether the Nahal Eshkol published here is itself authentic. It could be that it is indeed genuine, and the reference to the later book is an interpolation, but that is why we have to see the manuscript. After all, if the manuscript is written in one hand, and it includes the reference to the later book, then there is no doubt that it too is a forgery. So let the evidence about Sefer ha-Eshkol vol. 4, together with the manuscript, be placed on the Seforim Blog for all to see. Perhaps then we can begin to understand the mystery of this volume.

As long as the topic has been brought up, let me call attention to Shulamit Elitzur’s new book, Lamah Tzamnu (Jerusalem, 2007). On p. 115 n. 2, she gives an example where the Sefer ha-Eshkol forgery was perpetrated by using a quotation from the Shibolei ha-Leket, and cites a comment in this regard from the noted scholar Simhah Emanuel. On p. 235 n. 3,8 she mentions another example of forgery in the Auerbach Sefer Ha-Eshkol. For further instance, see Israel Moshe Ta-Shma’s posthumously published Keneset Mehkarim, vol. 4 (Jerusalem, 2010), p. 183 n. 28.4 In an article in Atarah le-Hayyim (Jerusalem, 2000), p. 292, Neil Danzig also points to a non-authentic interpolation in Auerbach’s Sefer ha-Eshkol. Yet I am surprised to see that he follows Ta-Shma in thinking that R. Moses De Leon might have had something to do with this.

In terms of traditional Torah scholars, I came across a comment by R. Avigdor Nebenzahl in R. Yaakov Epstein’s recently published Hevel Nahalato, vol. 7, p. 157. (Epstein is the grandson of Prof. Jacob Nahum Epstein.5) Nebenzahl comes from a German Orthodox background, so one might expect him to come to the defense of Auerbach, as did a number of prominent German Orthodox figures. Yet that is not what we find. Epstein had cited a passage from Auerbach’s Sefer ha- Eshkol to which Nebenzahl added that it is well known that some question the authenticity of this edition and claim that it is a forgery. In case you are looking for any non-scholarly motivations for this comment, I should mention that Nebenzahl’s sister was Plia Albeck (died 2005), the daughter-in-law of Hanokh Albeck and a significant person in her own right. (She paved the way for most of the Jewish settlements in the West Bank.) Hanokh Albeck, together with his father, Shalom Albeck, published the authentic Sefer ha-Eshkol, and were both very involved in exposing Auerbach’s forgery. In other words, Nebenzahl’s comment shows that families stick together. (Just out of curiosity, does anyone know if there have been any marriages between the two important families, the Auerbachs and the Albecks?)

In a previous post, I mentioned R. Yehiel Avraham Zilber’s belief that the Auerbach Sefer ha-Eshkol is forged. To the sources I referred to, we can add Birur Halakhah, Orah Hayyim 75. Also, R. Yisrael Tuporovitz, who has written many volumes of Talmudic commentaries, is not shy about offering his opinion. Here is what he writes in Derekh Yisrael: Hullin (Bnei Brak, 1999), p. 8:

וכבר נודע שספר האשכול הנדפס עם ביאור נחל אשכול הוא מזוייף ואין לסמוך עליו כלל

He repeats this judgment on pages 38, 53 and 345.

In one of the earlier posts I mentioned that R. Yitzhak Ratsaby denies the authenticity of Auerbach’s edition. I also quoted from his letter to me. At the time, I was unaware that portions of this letter also appear in his haskamah to R. Moshe Parzis’ Taharat Kelim (Bnei Brak, 2002). Another new source in this regard from Ratsaby is his Shulhan Arukh ha-Mekutzar (Bnei Brak, 2000), Yoreh Deah 138:3 (p. 287), where he accuses Auerbach of taking something from the Peri Hadash and placing it in Sefer ha-Eshkol.

Ratsaby discussed the Sefer ha-Eshkol in his haskamah to Parzis’ book because the latter had called attention to the defense of Auerbach in Tzidkat ha-Tzaddik. Here is the title page of the latter work.

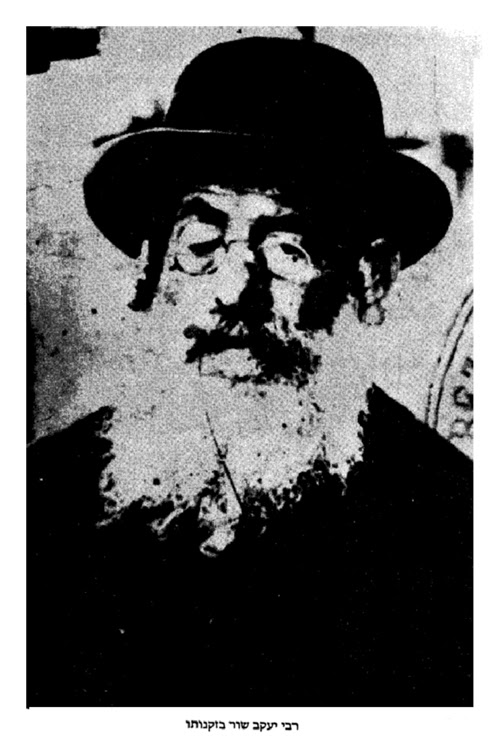

Among the defenders of Auerbach was R. Jacob Schorr of Kuty, Galicia. Schorr was a genius and is best known for his edition of the Sefer ha-Itim.6 He also wrote the responsa volume Divrei Yaakov (Kolomea, 1881), and a second volume, culled from various sources, both published and manuscript, appeared in 2006. Here is his picture, taken from Aharon Sorasky’s Marbitzei Torah me-Olam ha-Hasidut, vol. 3, p. 11.

It is an unfortunate oversight that this incredible scholar does not have an entry in the Encyclopaedia Judaica. A list of all of his works can be found in the introduction to his Mavo al ha-Tosefta (Petrokov, 1930). This introduction also contains R. Zvi Ezekiel Michaelson’s biography of Schorr. As with everything written by this amazing bibliophile,7 one learns a great deal, not only about the subject he focuses on, but about all sorts of other things.8 Michaelson was killed in the Holocaust and numerous unpublished manuscripts of his were lost. His grandson was Prof. Moshe Shulvass, and a responsum is addressed to him in Michaelson’s Tirosh ve-Yitzhar, no. 158.

Schorr’s son was Dr. Alexander Schorr, who translated many classic Greek and Latin texts into Hebrew.9 Alexander Schorr’s grandson is the well-known Israeli film director, Renen Schorr.10

Since Prof. Leiman has just written about the Maharal, it is worth noting that Schorr tells an incredibly far-fetched story, which he actually believed, about the Maharal and Emperor Rudolph. According to the tale, Rudolph’s biological father was a Jewish man. What happened was that Rudolph’s mother, the queen, could not have children with the Emperor. She therefore asked a Jewish man to impregnate her or else she would unleash persecution on the Jews in the kingdom. Upon hearing this, the beit din gave the man permission to accede to her wishes. I don’t want to repeat any more of this nonsensical story, but those who are interested can find it in R. Abraham Michaelson’s Shemen ha-Tov (Petrokov, 1905), pp. 60a-b. (R. Abraham was R. Zvi Ezekiel’s son.)

Returning to Schorr, one of the most astounding examples of self-confidence—others will no doubt call it arrogance or foolishness—ever stated by a rabbi (in print, at least) was penned by him. In his Meir Einei Hakhamim, reprinted in Kitvei ve-Hiddushei ha-Gaon Rabbi Yaakov Schorr (Bnei Brak, 1991), p. 177, we find the following:

ואני מעיד עלי שמים וארץ כי לא היה ולא יקום עוד אחרי שום חכם אשר יהי’ בקי בטוב [!] בפלפול תנאים ואמוראים כמותי

This text is often quoted by R. Yaakov Hayyim Sofer in his various works.11 This is not the only time Schorr expressed himself this way. On page 129 he writes

ודע דהופיע רוח הקודש בבית מדרשי

(This expression can also be found in other books, and originates in Rabad’s hassagah to Hilkhot Lulav 8:5. But to see this type of language in a sefer written by a someone very young [see below], even a genius like Schorr, is a bit jarring.) Sofer, Shem Betzalel, p. 28, also points to Meir Einei Hakhamim, p. 209, where Schorr writes about one of his ideas:

וזה נכון יותר מפירוש רש”י

(On this page, Schorr alludes to R Zvi Hirsch Chajes, referring to him as אחד מחכמי הזמן. Sofer claims that Schorr’s general practice is to not mention Chajes by name. Sofer wants the reader to think that he doesn’t know why Schorr acts this way. Yet the reason is obvious, and Sofer himself certainly knows that some talmudists were not fans of Chajes.)

Perhaps we can attribute Schorr’s over-the-top comments to his own immaturity. After all, as Sofer, Shem Betzalel, p. 29, points out, Schorr began writing the book I am quoting from at age thirteen, and completed it by the time he was sixteen. A genius he certainly was, yet I think we should assume that his excessive comments were the product of youthful exuberance. Sofer sees Schorr’s youthfulness as also responsible for the very harsh way he criticizes the writings of various gedolim, which is something that is more understandable, and forgivable, in a teenager than in a mature scholar. I think all writers are embarrassed of things their penned in their youth, and that is to be expected.12 An example I often mention in this regard (when not referring to myself) is Hirsch’s harsh criticism of Maimonides. This appeared in Hirsch’s first book, the Nineteen Letters, published when he was 28 years old. Never again in Hirsch’s many writings does he ever express himself this way. My assumption is that he regretted what he wrote, and in his mature years he would not have used such strong language. Similarly, I wonder if in his mature years R. Soloveitchik would have commented to R. Weinberg—as he did in his twenties—that his grandfather had a greater understanding than even the Vilna Gaon. (I have printed Weinberg’s letter where this appears in a few different places, most recently on the Seforim Blog and in the Hebrew section to my Studies in Maimonides.)

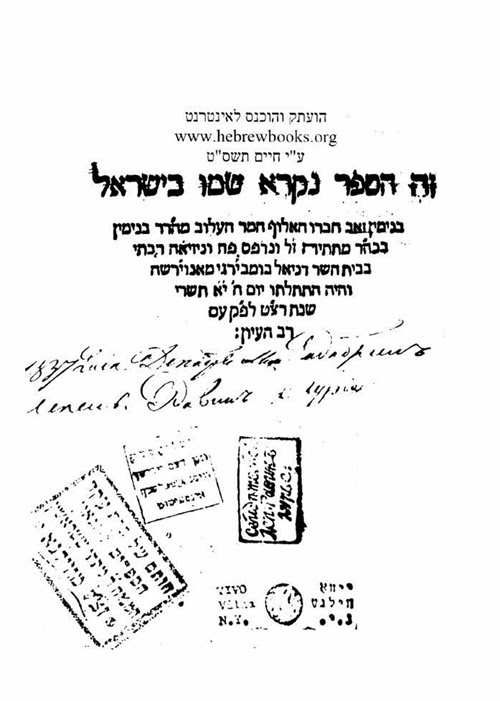

In terms of young achievers in the Lithuanian Torah world, I wonder how many have ever heard of R. Meir Shafit. He lived in the nineteenth century and wrote a commentary on the Jerusalem Talmud, when not many were studying it. Here is the title page of one of the volumes, where it tells us that he became rav of a community at the age of fifteen.

The Hazon Ish once remarked that the young Rabbi Shafit would mischievously throw pillows at his gabbaim!13

Returning to Schorr and Sefer ha-Eshkol, Ratsaby is not impressed by Schorr’s defense. He notes that in R. Yaakov Hayyim Sofer’s Torat Yaakov, Sofer states that the ideas of Schorr “צריכים בדיקה.”

I found the comment in Torat Yaakov (2002 edition) p. 880. Here Sofer claims that despite his brilliance, Schorr often puts forth unsustainable suppositions, and he calls attention to R. Reuven Margaliot, Ha-Mikra ve-ha-Mesorah, ch. 12. Here Margaliot cites a suggestion by Schorr that the text of Kiddushin 30a should be emended because the vav of גחון is not the middle letter of the Torah. Schorr further states that the editor of Masekhet Sofrim was misled by the error in the Talmud. The implication of Schorr’s comment is that all of our sifrei Torah are mistaken, for they mark this letter as special. Margaliot responds:

ותמה אני על תלמיד חכם מובהק כמוהו איך הרשה לעצמו לחשוב על מסדר מסכת סופרים שהוא טועה ומטעה וגם בודה מלבו מנהגים בכתיבת ס”ת. ב”הגהות” כאלו יכולים לעשות כל מה שרוצים, וכאשר כתב הגר”א [אליהו] פוסק בפסקי אליהו שם: רעדה אחזתני לעשות טעות כזה בגמרא ולחשוב על כל הס”ת שגיונות בדקדוקים דו’ דגחון ודרש דרש.

With regard to Ratsaby, I should also note that his dispute with R. Ovadiah Yosef continues unabated. In his recent Ner Yom Tov (Bnei Brak, 2008), pp. 20-21, he goes so far as to accuse R. Ovadiah of plagiarism.

He also states, with regard to R. Ovadiah (p. 100):

שכבוד התורה אצלו, הוא רק למי שמסכים לדבריו

Ratsaby’s book was written to defend the Yemenite practice of not making a blessing on Yom Tov candles against the criticism of R. Ovadiah. He also deals with R. Ovadiah’s larger point that the Yemenites must embrace the Shulhan Arukh’s rulings now that they are in the Land of Israel. The entire Yemenite rabbinate agrees with Ratsaby’s position, but upon seeing how he attacked R. Ovadiah, the condemnation of him from other Yemenite rabbis was swift. All I can say in defense of Ratsaby is that R. Ovadiah has been criticizing him in a less than respectful way for some time now. But in a sense, Ratsaby got what was coming to him, because for many years he has been writing very disrespectfully about R. Kafih.

In this new book, p. 98, Ratsaby goes so far as to repeat the legend that when Kafih was appointed a dayan in Jerusalem he swore to R. Ovadiah that he accepted the Zohar, and Ratsaby claims that Kafih swore falsely. Kafih, however, denied that he ever took such an oath.14 For a long time Ratsaby has been proclaiming that it forbidden to use Kafih’s books, as he is a member of the kat, i.e., the Dardaim who don’t accept the Zohar or Kabbalah in general. Yet R. Ovadiah has declared that the Dardaim are not to be regarded as heretics.15 This is in contrast to R. Chaim Kanievsky who holds that the Dardaim are heretics who cannot be counted in a minyan.16 R. David Teherani states that since the Dardaim reject the Zohar, their wine is yein nesekh.17 According to Aaron Abadi, R. Shlomo Zalman Auerbach also ruled that rejection of the Zohar and Kabbalah is heresy.18

I can understand those who assert that one must believe that the Zohar was written by Rashbi or at the very least that it was written be-ruah ha-kodesh, and if you deny this it is heresy. Yet what is one to make of the following statement, which greatly enlarges the realm of heresy (R. Menasheh Klein, Mishneh Halakhot, vol. 7, no. 160):

ואם הוא אינו מאמין שהמ”ב [משנה ברורה] נכתב ברוה”ק אזי הוא בכלל אפיקורוס וכופר בתורת ה’ . . . יש בזמן הזה שאין מאמינים שגם בדורינו אנו ישנם חכמי הזמן שיש להם רוה”ק . . . ומי שלא מאמין בזה הרי הוא אפיקורוס וכופר בלי ספק.

Based on this definition, I think the entire Lithuanian rabbinate until World War II would be regarded as heretics. Would such a statement even have been imaginable before twenty years ago? It is, of course, no secret that the Lithuanian rabbinate has been transformed along hasidic lines. This change is undeniable and I can point to many examples of this. Here is one (which was sent to me by R. Yitzhak Hershkowitz).

Would any Jew in Lithuania ever fall for such a thing as magic (or holy) wine? Anyone who tried to peddle this stuff would have been thrown out of the beit midrash. I was actually told an anti-hasidic joke with regard to this picture. I ask all Hasidim not to be offended as neither I nor the management endorse the joke. Yet it deserves to be recorded for posterity, for as we all know, jokes are simply jokes, but the history of jokes (even bad ones), well that is scholarship. The joke goes as follows: “It is incredbible. We now see great Lithuanian Torah scholars doing things that until now only hasidic rebbes did. But even more incredible would be to see the reverse, that is, to see hasidic rebbes write seforim on Shas and poskim.”

With regard to the Zohar, I must mention an amazing point called to my attention by David Zilberberg, from which we see that R. Joseph B. Soloveitchik did not believe that R. Simeon bar Yohai wrote the Zohar, or at least that he didn’t write all of it. I always assumed as much, but as far as I know there was never any proof, until now. In The Lord is Righteous in All His Ways, pp. 206-207, the Rav discusses the Western Wall and says that there is no mention of it in Chazal and very little mention in rishonim. The Wall is mentioned in Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah 2:2219, where it states that the Kotel will never be destroyed, but the Rav says about this Midrash:

I will tell you frankly that I am always suspicious about this midrash, because the classical sources, the Bavli and the Yerushalmi, do not mention the Kotel ha-Ma’aravi. The midrash cited earlier is, perhaps, a later insert. Apparently, Rabbi El’azar ha-Kalir knew the midrash. To my mind, this kinah of Rabbi Elazar ha-Kalir is one of the earliest documents to mention the Kotel ha-Ma’aravi.

Earlier in this book the Rav tells us when Kalir lived:

I do not know why historians have to explore when Kalir lived when he himself states that nine hundred years have passed and the Messiah has not yet arrived. It means that Kalir lived in the tenth century.

Yet as Zilberberg correctly points out, the Western Wall is seen as quite significant in the Zohar (II, 5b), and is referred to as Rosh Amanah.20 The Rav knew the Zohar very well, and therefore, when he tells us that Chazal do not mention the Western Wall, and it is only during the time of the rishonim that we begin to see references to it, he is also telling us that the Zohar (or at least this section of the Zohar) was written in the days of the rishonim.

Returning to Auerbach, let me add in conclusion that he is not the only great rabbi and Torah scholar who was involved in forgery. An earlier case is R. Benjamin Ze’ev of Arta (sixteenth century), author of the well known responsa volume Teshuvot Binyamin Ze’ev. Here is the title page from the first edition (Venice, 1539):

In the midst of a dispute he was involved in, he forged the signature of the Venetian rabbi, R. Baruch Bendit Axelrad, placing it on a document that supported himself. He also forged an entire letter in R. Baruch Bendit’s name. When all this was discovered, it helped lead to R. Benjamin’s downfall.21

Quite apart from the forgery, R. Solomon Luria, Yam Shel Shlomo, Bava Kamma, ch. 8 no. 72, also accuses R. Benjamin Zev of plagiarism. Here are some his words:

כל דבריו גנובים וארוכים בפלפול שאינו לצורך וכנגד פנים מראה אחור . . . ושרי לי מרי אם הוא צדיק למה הביא הקב”ה תקלה על ידו הלא הוא היה הכותב ונתן לדפוס הספר מידו ומפיו.

One big question that needs to be considered is how far removed is forgery from false attribution? When it comes to false attribution there is a long rabbinic tradition supporting it, and in the book I am currently working on I deal with this in great detail. If you can falsely attribute a position to a sage, perhaps you can forge a document in his name as well (assuming it is not done for personal gain). Could that be what was driving Auerbach?

* * *

A few people have sent me a question about my Monday night Torah in Motion classes, so I assume that there are others who have the question as well. Here is the answer: If you cannot be with us at 9PM and you are signed up, the classes are sent to you so that you can watch or listen at your convenience. This is much cheaper than downloading the classes individually.

Notes

1 From my post here you can find all the links.

2 See Anthony Grafton, Forgers and Critics: Creativity and Duplicity in Western Scholarship (Princeton, 1990), pp. 44-45.

4 As has been noted by many, Auerbach’s edition of Sefer Ha-Eshkol has misled countless talmidei hakhamim. There is another way in which Auerbach misled a scholar, but in this case it was accidental. In the introduction to his edition, p. xv note 9, Auerbach reports in the name of a supposedly reliable person that the Yerushalmi Kodashim was to be found in the Vatican library. This false report led R. Mordechai Farhand to travel there from Hungary in search of this treasure, and he describes his journey. See Farhand, Be’er Mordechai (Galanta, 1927), pp. 154ff. Farhand was a gullible fellow. See ibid. p. 152, where even though it had been a number of years since Friedlaender’s Yerushalmi forgery had been established, he didn’t want to take sides. The legend that there was a copy of the Yerushalmi Kodashim in the Vatican had been disproven already in the nineteenth century. See R. Baruch Oberlander in Or Yisrael (Tamuz 5761), p. 220.

5 In his review of my edition of Kitvei ha-Rav Weinberg, vol. 2, R. Neriah Guttel, Ha-Ma’ayan (Nisan 5764), pp. 82-83, writes that it was improper for me to publish Weinberg’ judgment of Epstein (p. 430). Although they were friends, and Weinberg thought that Epstein was a great scholar, he also pointed out that that Epstein wasn’t a lamdan. What Weinberg meant is that Epstein wasn’t a traditional talmid hakham but an academic Talmudic researcher. As such, while his publications had great value, in Weinberg’s eyes they didn’t get to the heart of what Talmudic scholarship should be about. In Weinberg’s words:

סוכ”ס אפשטיין אינו למדן, ואיננו אלא פילולוג בעל חוש חד. בלא לומדות אי אפשר לחקור לא את המשנה ולא התלמוד.

Statements like these are vital for evaluating Weinberg’s approach to academic scholarship, and I never would dream of censoring such things.

6 In his Sha’ar Yaakov (Petrokov, 1922), no. 16, there is a responsum to “Abraham Joshua Heschel.” Shmuel Glick, Kuntres ha-Teshuvot he-Hadash, vol. 3, s.v. Sha’ar Yaakov, assumes that this is the famous A. J. Heschel, but I don’t think we can conclude this based only on the name, which was shared by a number of others.

7 Eleh Ezkerah (New York, 1957), vol. 2, p. 196 (repeated in the Encylopaedia Judaica entry on Michaelson), states that in Michaelson’s Degan Shamayim (Petrokov, 1901), there are responsa written when he was twelve and thirteen years old. This is a mistake. The earliest responsa dates from when he was seventeen years old. See pp. 10a, 11a.

8 On p. 23 he prints a letter that Schorr wrote to Michaelson’s son, who wanted to translate the Sefer ha-Hinukh into Yiddish. Schorr was strongly opposed to this. He explained as follows, using words that won’t make the women very happy:

רבינו הרמב”ם והחינוך אחריו שהודיעו ברבים טעמי מצות וכו’ יכשלו בזה קלי הדעת לבטל המצוה כפי סכלות דעתם אשר לפי הטעם אין לחוש עוד בזמנינו וכיוצא שבטל בהם טעם זה וכו’ איך ניתן לגלות טעמי מצות גם בפני נשים ועמי הארץ אשר יקראו בו, חלילה לרו”מ לעבור על לפני עור.

9 See here

10 See here

11 Sofer often refers to a similar type of comment by R. Shlomo Kluger, Ha-Elef Lekha Shlomo, Orah Hayyim 367:

אם הייתי זוכר כל מה שכתבתי מעולם לא הי’ שום הערה בעולם שלא הרגשתי בזה.

(I cited both Schorr and Kluger in a footnote in my article on the Hatam Sofer in Be’erot Yitzhak: Studies in Memory of Isadore Twersky. Although other writers also cite this comment of Kluger, as with much else, I believe that I first saw the reference in one of Sofer’s writings.) Kluger wrote so many thousands of responsa, that it is not uncommon for him to contradict himself and forget what he wrote previously. See R. Yehudah Leib Maimon, ed., Sefer ha-Gra (Jerusalem, 1954), p. 99 in the note. R. Solomon Schreiber, Hut ha-Meshulash (Tel Aviv, 1963), p. 19, claims that R. Nathan Adler’s reason for not recording his Torah teachings was due to a belief that the permission to put the Oral Law into writing only applies if one is not able to remember this information. Since, according to Schreiber, R. Nathan claimed that he never forgot any Torah knowledge, he was not permitted to take advantage of this heter.

12 Regarding Schorr being a childhood genius, this letter from him to R. Shlomo Kluger appeared in Moriah, Av 5767.

As you can see, the letter was written in 1860 (although I can’t make out what the handwriting says after תר”ך). We are informed, correctly, that Schorr was born in 1853, which would mean that he was seven years old when he wrote the letter. This, I believe, would make him the greatest child genius in Jewish history, as I don’t think the Vilna Gaon could even write like this at age seven. Furthermore, if you read the letter you see that two years prior to this Schorr had also written to Kluger. Are there any other examples of a five-year-old writing Torah letters to one of the gedolei ha-dor? Furthermore, from the letter we see that the seven-year-old Schorr was also the rav of the town of Mariompol! (The Mariompol in Galicia, not Lithuania.) I would have thought that this merited some mention by the person publishing this letter. After all, Schorr would be the only seven-year-old communal rav in history, and this letter would be the only evidence that he ever served as rav in this town. But the man who published this document and the editor of the journal are entirely oblivious to what must be one of the most fascinating letters in all of Jewish history. Yet all this assumes that the letter was actually written by Schorr. Once again we must thank R. Yaakov Hayyim Sofer for setting the record straight. In his recently published Shuvi ha-Shulamit (Jerusalem, 2009), vol. 7, p. 101, he calls attention to the error and points out, citing Wunder, Meorei Galicia, that the rav of Mariampol was another man entirely, who was also named Jacob Schorr.

18 See here. According to Abadi, R. Shlomo Zalman’s decision was made with regard to a well-known scholar who is very involved with Artscroll.

19 The Rav doesn’t note that there is a mention of the Wall in Shemot Rabbah 2:2 as well, but his judgment would no doubt be the same. Contrary to the Rav, since these midrashim are found in so many parallel sources, I don’t think there is any question that they indeed originate with Chazal.

21 The event is described in Meir Benayahu, Mavo le-Sefer Binyamin Ze’ev (Jerusalem, 1989), pp. 120ff. Once the dispute got going, all sorts things were said. R. Benjamin was even accused of purchasing his semikhah. See ibid., p.140. The source for this is R. Elijah ha-Levi, Zekan Aharon (Constantinople, 1534), no. 184.